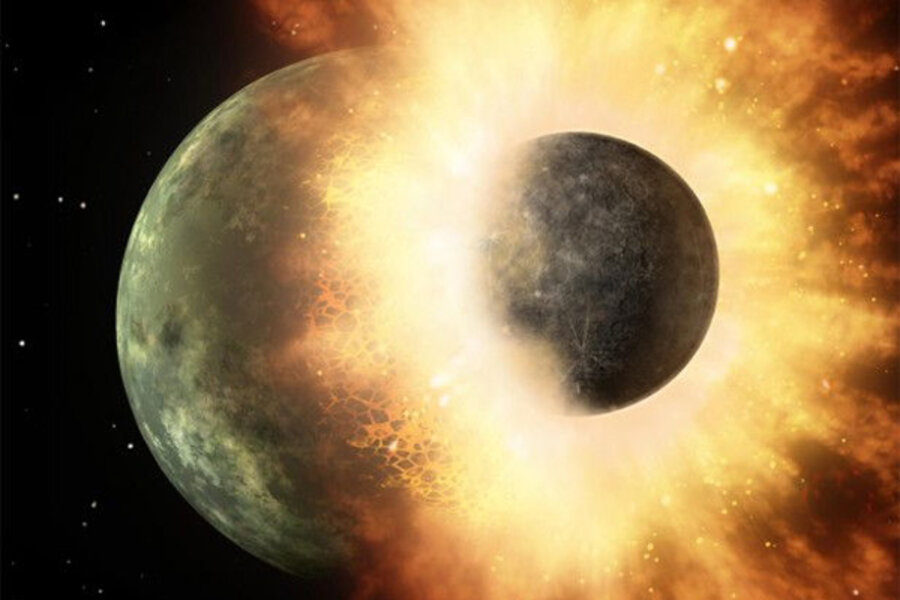

Moon formed from humongous Earth collision, new theories attempt to explain

Loading...

The moon did indeed coalesce out of tiny bits of pulverized planet blasted into space by a catastrophic collision 4.5 billion years ago, two new studies suggest.

The new research potentially plugs a big hole in the giant impact theory, long the leading explanation for the moon's formation. Previous versions of the theory held that the moon formed primarily from pieces of a mysterious Mars-size body that slammed into a proto-Earth — but that presented a problem, because scientists know that the moon and Earth are made of the same stuff.

The two studies both explain how Earth and the moon came to be geochemical twins. However, they offer differing versions of the enormous smashup that apparently created Earth's natural satellite, giving scientists plenty to chew on going forward.

A fast-spinning Earth

One of the studies — by Matija Cuk of the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute in Mountain View, Calif., and Sarah Stewart of Harvard — suggests the answer lies in Earth's rotation rate. [Video: New Ideas About the Moon-Forming Impact]

If Earth's day had been just two to three hours long at the time of the impact, Cuk and Stewart calculate, the planet could well have thrown off enough material to form the moon (which is 1.2 percent as massive as Earth).

This rotational speed might sound incredible, and indeed it's close to the threshold beyond which the planet would begin to fly apart. But researchers say the early solar system was a "shooting gallery" marked by many large impacts, which could have spun planets up to enormous speeds.

Cuk and Stewart's study, which appears online today (Oct. 17) in the journal Science, also provides a mechanism by which Earth's rotation rate could have slowed over time.

After the collision, a gravitational interaction between Earth's orbit around the sun and the moon's orbit around Earth could have put the brakes on the planet's super-spin, eventually producing a 24-hour day, the scientists determined.

A bigger impactor

Cuk and Stewart's version of the cosmic smashup posits a roughly Mars-size impactor — a body with 5 percent to 10 percent the mass of Earth. However, the other new study — being published in the same issue of Science today — envisions a collision between two planets in the same weight class.

"In this impact, the impactor and the target each contain about 50 percent of the [present] Earth's mass," Robin Canup, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo., told SPACE.com via email.

"This type of impact has not been advocated for the Earth-moon before (although a similar type of collision has been invoked for the origin of the Pluto-Charon pair)," Canup added, referring to the largest moon of Pluto.

In her computer models, the symmetry of this collision caused the resulting moon-forming debris disk to be nearly identical in composition to the mantle of the newly enlarged Earth.

Canup's models further predict that such an impact would significantly increase Earth's rotational speed. But that may not be a big issue, since Cuk and Stewart's work explains how Earth's spin could have slowed over time.

A third study, published today in the journal Nature, determined that huge amounts of water boiled away during the moon's birth. The finding, made by examining moon rocks brought back to Earth by Apollo astronauts, further bolsters the broad outlines of the giant impact theory.

Though the gigantic smashup occurred 4.5 billion years ago, scientists may one day be able to piece together in detail how it all went down, Canup said.

"Models of terrestrial planet assembly should be able to evaluate the relative probability of, e.g., the collision I advocate vs. the one proposed by Cuk and Stewart," she said.

Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also onFacebook and Google+.