Asteroid flyby: No danger this time, but astronomers are taking lots of notes

Loading...

A dark asteroid nearly two miles wide and its tiny moon will flit through Earth's neighborhood Friday.

The flyby – with closest approach occurring at 4:59 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time – represents one of the best opportunities this year for astronomers to take an up-close-and-personal look at an object of keen scientific interest as well as one on the potentially-hazardous list.

Although the object won't be visible to the naked eye or even visible in binoculars, the asteroid, known as 1998 QE2, should be visible through a modest-sized telescope for the first few days of June, researchers say.

If the slowly tumbling QE2 were to strike Earth it would make for a truly bad-hair day for the planet. The asteroid presents no threat to Earth during this visit or during its next "closest" approach more than 200 years from now, in 2221. Its path around the sun is bringing it to within 3.6 million miles of Earth Friday, and only slightly closer two centuries from now.

But 1998 QE2 falls within a class of asteroids known as Amors. Generally, Amors follow orbits that on closest approach to the sun bring them near Earth's orbit without crossing it. QE2, for instance, comes to within 1.049 astronomical units (AU) from the sun before heading back out to its most distant point at 3.8 AU – where the main asteroid belt lies. Earth orbits the sun at an average distance of 1 AU.

Over time, however, gravitational interactions with Earth and Mars, and even subtle factors such as pressure from sunlight, can tweak an Amor's orbit in ways that ultimately will send it across Earth's path. QE2 swings close enough to Earth to bear watching.

In addition, opportunities to study an object this size from the comfort of Earth are relatively rare.

Using radar, when the opportunity does present itself, "we can collect data that compares only to a spacecraft flyby, and for much less money," says Marina Brozovic, a researcher at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory who is leading the radar observations of the object.

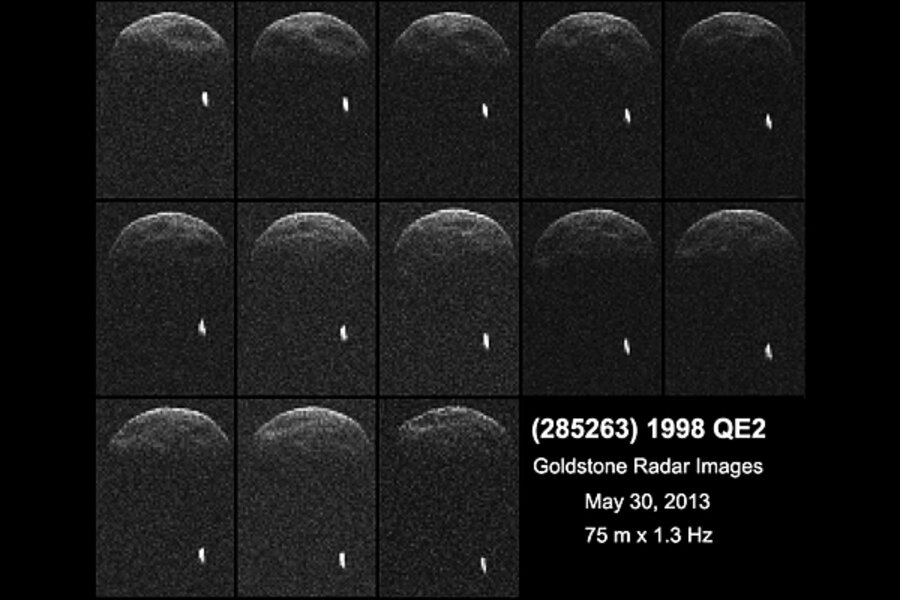

On Wednesday, a 230-foot-wide radar antenna at NASA's Goldstone Deep Space Tracking Center outside of Barstow, Calif., began tracking the QE2 and immediately discovered that the 1.7-mile-wide asteroid was not alone. It has a 2,000-foot-wide moon orbiting it – an object about 30 times the size of the small asteroid that exploded over the Chelyabinsk region of Russia in February.

The presence of a companion, relatively common among near-Earth asteroids, represents a bonanza, Dr. Brozovic says, because their orbital dance allows researchers to get precise estimates of the larger object's mass. Radar also delivers a precise size for each object. The size and mass can be parlayed into an estimate of the QE2's density, which yields clues about its structure and bulk composition.

Finally, the asteroid's size and brightness can be correlated in ways that allow asteriod-search programs to better estimate the sizes of the objects they detect – important to estimating any collision hazard. The QE2 is extremely dark, putting it in a class of objects known as carbonaceous chondrites – stony objects thought to have helped deliver to Earth the inventory of chemicals needed to serve as the building blocks for organic life.

In addition to Goldstone's radar, the 1,000-foot-wide radio telescope at Arecibo in Puerto Rico will join the observing campaign beginning June 6. Working in tandem, data from the two observatories should allow scientists to spot details as small as 12 feet across on QE2's surface.

Finally, optical telescopes in the Southern Hemisphere will be gathering observations through August to pin down more accurately the object's rotation rate and its chemical composition.

Asteroid 1998 QE2 was discovered in 1998 by MIT's LINEAR asteroid search. The asteroid and its moon make one trip around the sun every 3.77 years.

While astronomers track QE2, they also are celebrating an important milestone for a mission to return samples from another, QE2-like asteroid. Two weeks ago, NASA gave the green light to develop and launch OSIRIS-REx, a spacecraft that is slated to visit asteroid 1999 RQ36. It's a half-mile-wide object that does cross Earth's orbit and is listed as a potentially hazardous object late in the 22nd century.

The mission would launch in 2017 and reach the asteroid two years later for a two-year stay, returning samples to Earth in late 2023. Researchers picked the object because it's carbon rich. And the mission design – orbiting and sampling for two years – represent the kind of mission needed to provide information on how best to deflect an asteroid if it does look as though it has Earth in its crosshairs.