Scientists discover ancient caribou hunting site beneath Lake Huron

Loading...

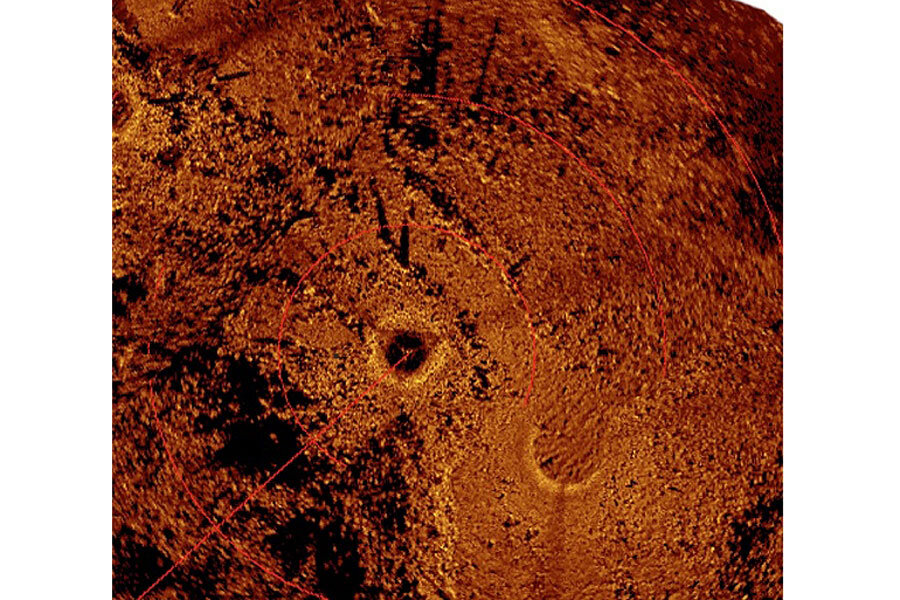

An elaborate array of linear stone lanes and V-shaped structures has been discovered on an underwater ridge in Lake Huron, marking what is thought to be the most complex set of ancient hunting structures ever found beneath the Great Lakes, according to a new report.

Researchers based at the University of Michigan think the roughly 9,000-year-old-structure helped natives corral caribou herds migrating across what was then an exposed land-corridor — the so-called Alpena-Amberley Ridge — connecting northeast Michigan to southern Ontario. The area is now covered by 120 feet (347 meters) of water, but at the time, was exposed due to dry conditions of the last ice age.

Using underwater sonar and a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) equipped with a video camera, the researchers found two parallel lines of stones that create a 26-foot-wide (8 meters) and 98 foot-long (30 m) northwesterly-oriented lane that ends in a natural cul-de-sac. The team also found what appear to be V-shaped hunting blinds oriented to the southeast, and a rectangular area that may have been used as a meat cache, according to the researchers. The entire feature spans an area of about 92 feet by 330 feet (28 by 100 m), the team reports. [See Images of Ancient Hunting Structures Under Lake Huron]

Scuba-trained members of the team investigated the site, and found 11 chipped stone flakes nearby the lanes, providing further evidence that the area was used as a hunting ground. The researchers think the flakes would have been used to repair and maintain stone tools.

Using a computer simulation, the team predicted where the caribou would have traveled during spring and autumn migrations, and identified two main choke points where the herds likely would have converged during both seasons. One of the two choke points fell directly within the newly discovered feature.

"The fact that all of the migrations tend to converge on these two locations ... would have provided predictability for ancient hunters, which is why we see so many structures located in these spots," study co-author John O'Shea, a researcher at the Museum of Anthropological Archaeology at the University of Michigan, told Live Science.

Autumn was the preferred season for caribou hunting, because the animals were at their fattest and their hides were of highest quality at that time of year. Even so, the distinct orientations of the lanes and V-shaped structures show that the hunters would have been able to intercept the animals in both the autumn — when the caribou traveled southeast for the winter — and the spring — when the herds traveled northwest back up to their breeding grounds. The setup and size of the structures also suggests the hunters used different strategies during the two seasons, with large groups of hunters likely working together in the spring, and smaller groups working independently in the autumn, the team reports.

"We were surprised by the apparent seasonal differences between the different kinds of structures," O'Shea said.

Similar structures have been found in the North American Arctic, but few have been preserved in temperate regions due to disturbance by subsequent settlers for farming or road construction, O'Shea said. The calm underwater environment ofLake Huron helped keep the structures remarkably intact, and their position offshore allowed it to remain unobscured by sediment that settles closer to shore.

The team plans to continue mapping the structure more thoroughly this spring, and will also investigate the second choke point identified by their computer simulation, O'Shea said.

The study findings are detailed today (April 28) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow Laura Poppick on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science.

- Image Gallery: Stone Structure Hidden Under Sea of Galilee

- The Great Lakes: North America's 'Third Coast'

- Gallery: Aerial Photos Reveal Mysterious Stone Structures

Copyright 2014 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.