What is the planet Mercury made of? Space probe data reveals clues.

Loading...

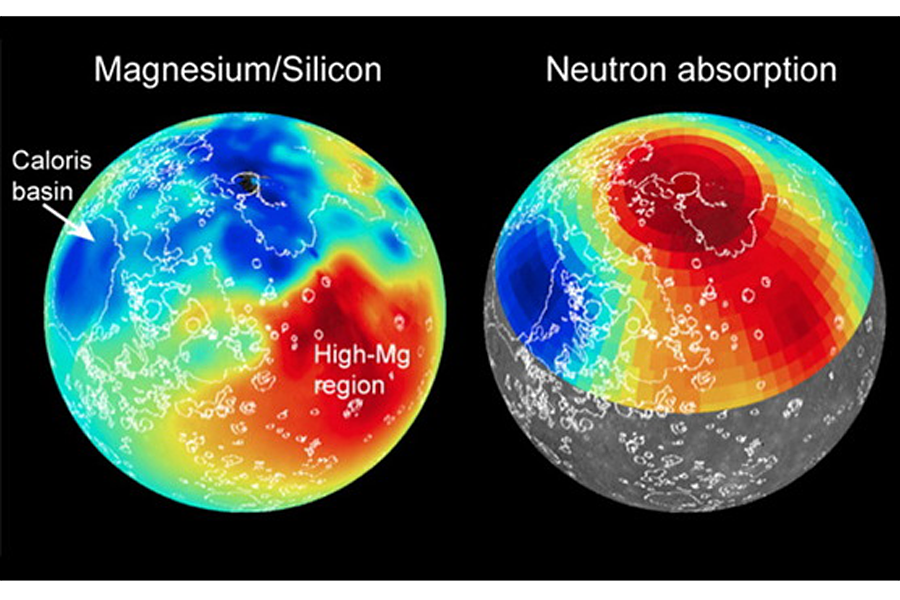

Two new maps of Mercury taken by a NASA probe have identified never-before-seen formations on the planet's surface.

The previously unidentified regions of Mercury have compositions that differ significantly from the crust around them. Known as geochemical terranes, these zones provide insight into the formation of the outer skin of the planet. The maps appear in two new studies, which suggest that the most recently identified features may have formed not from the planet's crust but from just below it, in the mantle.

Created using the X-Ray Spectrometer (XRS) and Gamma-Ray Spectrometer (GRS) instruments on NASA's MESSENGER probe, the maps are used to study the surface chemistry of Mercury, the closest planet to the sun. This analysis will provide information about the concentrations of elements like potassium, uranium and sodium on Mercury's surface. The experiment will also provide scientists with ratios of silicon to other elements on the planet's surface. [See more Mercury photos by NASA's MESSENGER]

The first study used the XRS to produce the first global geochemical maps of Mercury, using a novel method performed for the first time on a planetary scale. By studying X-rays streaming from the sun, the authors were able to examine the composition of geochemical terranes on the planet.

"The consistency of the new XRS and GRS maps provides a new dimension to our view of Mercury's surface," lead author Shoshana Weider, of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, said in a statement. "The terranes we observed had not been previously identified on the basis of spectral reflectance or geographical mapping."

The most obvious of these unusual terranes is a large feature that covers more than 3 million square miles (5 million square kilometers) of the planet's surface. This terrane exhibits the highest observed ratios of silicon to each of the elements of magnesium, sulfur and calcium, as well as some of the lowest aluminum-to-silicon ratios on the planet, according to a new paper published this week in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

One possible explanation for the unusual region is that it stems from an impact that occurred long ago. The exposed mantle could have aided in the creation of the extremely large feature.

A second map used GRS to trace the absorption of low-energy ("thermal") neutrons across the surface of Mercury. This map shows the distribution across Mercury's northern hemisphere of elements that absorb thermal neutrons. By combining that information with previously obtained data, the authors were able to identify four distinct geochemical terranes on the planet.

The Caloris basin on Mercury, the planet's largest well-preserved impact basin, contains smooth interior plains that the new results reveal have a distinct composition from other volcanic plains on the planet. According to the authors, these plains formed by partial melting of the mantle.

"Earlier MESSENGER data have shown that Mercury's surface was pervasively shaped by volcanic activity," Patrick Peplowski, of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory and lead author of the paper concerning the second map, said in the same statement.

"The magmas erupted long ago [and] were derived from the partial melting of Mercury's mantle," he said. "The differences in composition that we are observing among geochemical terranes indicate that Mercury has a chemically heterogeneous mantle."

The second study appeared online in the journal Icarus.

"The crust we see on Mercury was largely formed more than 3 billion years ago," said Larry Nittler, deputy principle investigator of the mission and co-author on both studies. "The remarkable chemical variability revealed by MESSENGER observations will provide critical constraints on future efforts to model and understand Mercury's bulk composition and the ancient geological processes that shaped the planet's mantle and crust."

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

- Our Solar System: A Photo Tour of the Planets

- Messenger: New Views of Mercury

- Most Enduring Mysteries of Mercury

Copyright 2015 SPACE.com, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.