Can 149 climate pledges forestall ocean ecosystem collapse?

Europe’s climate change commissioner is smiling, but some scientists have worry lines.

As nations prepare for a global conference on climate change, an “astounding” 149 governments have pledged to cut down on carbon emissions, Miguel Arias Cañete said Tuesday, something he wouldn’t have thought possible just six months ago.

“There are many, many reasons to be cheerful,” Commissioner Cañete told the BBC. “The fact that 149 countries to date have presented the United Nations their commitments to fight global warming is astonishing.”

These new policies would limit the predicted rise in global temperature from between 3.8 degrees and 4.7 degrees Celsius to about “3 [degrees] C maximum,” Cañete said.

“That's a big step, although clearly it's not enough,” he added. The temperature increase needs to be brought down to about 2 degrees C to be deemed safe for most countries, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

But even as nations around the world take steps to protect humans from carbon emissions, scientists are investigating their impact on underwater life – and the picture is sobering.

If emissions keep climbing, say marine ecologists at the University of Adelaide, ocean ecosystems will be severely threatened by 2100.

Many scientists have studied various, scattered effects of climate change and ocean acidification, but now those studies are building into one comprehensive look at the oceanic effects of climate change, published Tuesday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Until now, there has been almost total reliance on qualitative reviews and perspectives of potential global change,” said marine ecologist Sean Connell, co-author of the study, in a statement. “Where quantitative assessments exist, they typically focus on single stressors, single ecosystems, or single species.”

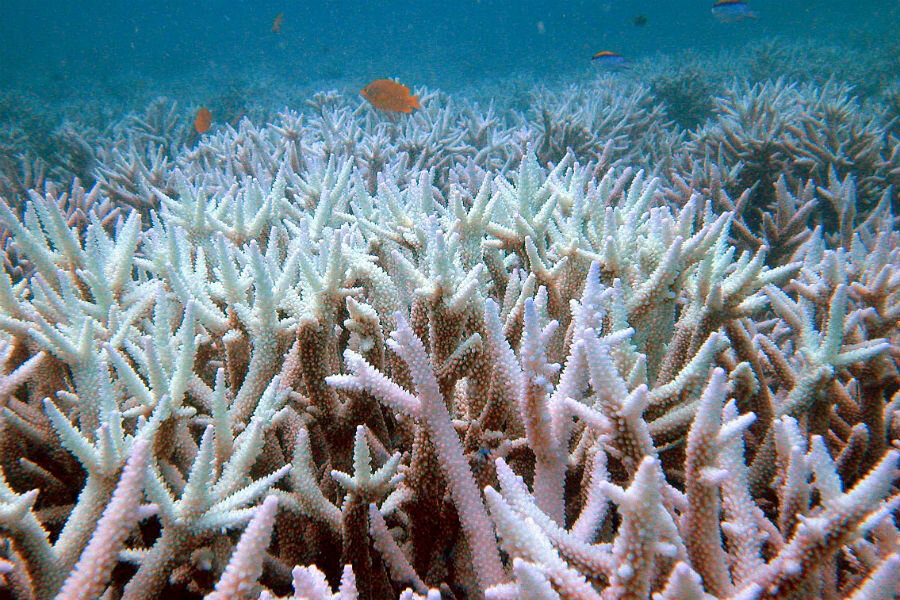

Professors Connell and Ivan Nagelkerken analyzed more than 630 published experiments, ranging from the bleaching of coral reefs to the competitive strengths of seaweeds to the effects of global warming on sharks’ hunting behavior.

They found that “more than half of the world’s ocean has experienced an increase in cumulative human impact over a 5[-year] time span, predominantly driven by increasing climate stressors such as sea surface temperature, ocean acidification, and UV radiation.”

Sea creatures' abilities to adapt to the warming ocean will be “limited,” warned the scientists. They predict shrinking sea populations and widespread extinctions if climate change is not curbed.

Some plankton species will flourish in warmer waters, reports The Christian Science Monitor, but on the whole, “there will be a species collapse from the top of the food chain down,” predicts Professor Nagelkerken.

“With higher metabolic rates in the warmer water, and therefore a greater demand for food, there is a mismatch with less food available for carnivores – the bigger fish that fisheries industries are based around,” he added.

For now, the climate change pact is a step in the right direction. The world’s biggest economies are leading the way, Jacquie McGlade, chief scientist of the UN environment programme, told the BBC.

"When [smaller] countries saw the big players – the EU, the USA – put their figures on the table, there's a bit of copycat – which is a good thing,” she said. “This is going to be a race to the top, not the bottom.”