A replacement for diamonds? Scientists discover Q-carbon

The process of making a diamond is nothing short of laborious.

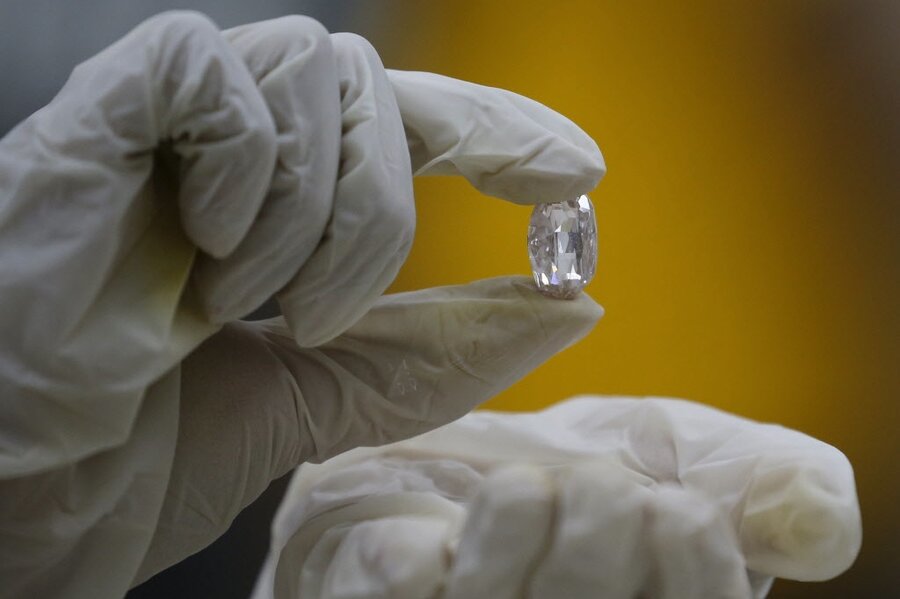

Made from a highly organized carbon, diamonds form naturally after being buried 100 miles deep into the earth’s core, where they are heated and pressurized at about 2,200 degrees Fahrenheit, until cooling to their solid form. Humans however, have found ways to simulate these conditions in laboratories to produce manmade diamonds.

But after decades of testing, a team from North Carolina State University has invented a way to expedite the diamond-making process – and it doesn’t involve compressing carbon under extreme pressure.

Dubbed “Q-carbon,” the new diamonds are magnetic at room temperatures, more robust than diamonds, and let off a small glow. Scientists discovered Q-carbon by shooting loose carbon through a laser beam for 200 nanoseconds to melt “amorphous diamond like carbon.”

“Converting carbon to diamond has been a cherished goal for scientists all over the world for the longest time,” wrote Jagdish Narayan, lead author on the paper published this week in the Journal of Applied Physics.

More than an alternative for making cheaper, faster diamonds, Q-carbon will likely be used for medicinal purposes – like nanoneedles, microneedles, nanodots and films. Using the Q-carbon method is less expensive because it already relies on lasers used in laser eye surgeries. The lasers can grow the diamonds in a matter of seconds.

But even more, it’s a way for scientists to understand how magnetism may work on other planets that don’t have active dynamos.

“We’ve now created a third solid phase of carbon,” Narayan told CNN. “The only place it may be found in the natural world would be possibly in the core of some planets.”

Diamonds have been mined for over 2,000 years, and were used by first-century Romans to carve cameos. They’ve since been used as a symbol of preciousness, wealth, and power. In 1947, an ad agency famously coined the term “diamonds are forever.”

The diamond industry shifted after the discovery that synthetic diamonds could be produced inside laboratories, which reduced the price of diamonds but didn’t drive the market down. Whether Q-carbon will drive down the diamond industry’s prices is unclear. But scientists seem hopeful about the potential discoveries the Q-carbon may bring.

“Having a new way to create [diamonds] – especially one that voids a lot of the infrastructure of the old methods – is great,” physicist Keal Byrne, a postdoctoral fellow at the Natural History Museum told Smithsonian. “It’s’ a really interesting discovery. [But] what comes from it – now that’s the interesting part.”