How Saharan desert ants use their silver hairs to keep cool

Forget the sunscreen – these ants have metallic hairs to block the harsh sun.

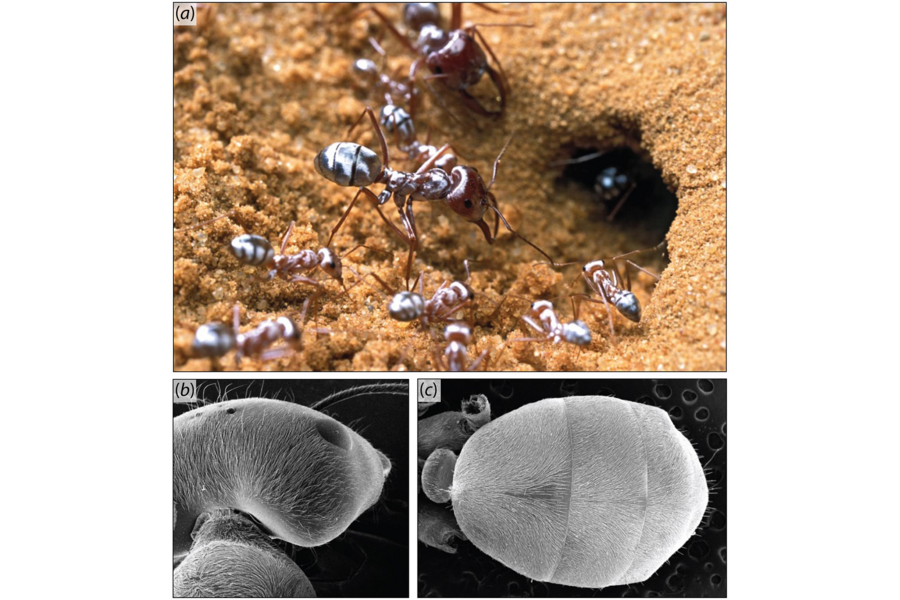

Saharan silver ants, or Cataglyphis bombycina, are known for their resistance to searing desert heat. In a new optical study, researchers from the Université Libre de Bruxelles in Belgium pinpointed the geometric properties that keep these bugs cool. Triangular hairs, they say, reflect sunlight like tiny mirrors and give the ants their chrome-like appearance. The new study was published Wednesday in the open access journal PLOS ONE.

Most of the Sahara's native animal species emerge only at the coolest points in the day, when the brutal sun is low or absent. Many Saharan predators would gladly snack on a silver ant, except for one thing – these lustrous bugs leave their dens only at the day's hottest point.

With the help of special heat shock proteins, Saharan silver ants brave temperatures up to 128 degrees Fahrenheit to scavenge dead insects. Any more than 10 minutes in the desert sun spells death for these ants, so they sprint 70 times their body length every second.

But even more impressive than C. bombycina’s speed is its shiny silver coat.

Last year, researchers at Columbia University used infrared cameras to study the unusual thermal-radiative properties of silver ant hair. They found that the hairs scattered light differently across the light spectrum, blocking incoming sunlight and dissipating thermal radiation upon heating.

In the new PLOS ONE study, researchers used scanning electron microscopes to trace the paths of light rays as they came into contact with the hair. The results seemed to support the conclusions of the earlier study.

Most hair, ours included, has a more or less cylindrical shape. But silver ant hairs have an unusual triangular cross section, according to the authors of the new paper. And while most animal hairs make direct contact with the cuticle, the outer layer of cells on the hair, silver ants have an extremely thin layer of air between each hair and its cuticle.

“The hairs work as prisms reflecting light,” says paper co-author Serge Aron. “This reflection proceeds within each hair: the light enters the prisms, but it is reflected on the basal plane of each hair. If the hairs were in contact with the cuticle, no reflectivity would be expected.”

Dr. Aron and his colleagues used micro-thermometers to determine the heating rates of both hairy and shaved silver ants. They found that the mirror-like hairs reflected more than 90 percent of incoming light and kept the ants up to 3 degrees cooler. This total internal reflection (TIR) prevents overheating and is also responsible for the silver ant’s characteristic sheen. Aron and colleagues believe this may be “the first case of TIR to account for the color of an animal.”

It’s hard not to admire the simple efficiency of this mechanism. As such, these biological structures are already inspiring new human technology – researchers are already working to create synthetic materials that mimic the radiative cooling effect of silver ant hair.

“Over the last decades, biomimicry has led to many important technological developments and is a very active area of research,” Aron says. “High reflectance is important both to keep objects cool in the presence of strong sunlight, and to keep objects warm by preventing radiative cooling. The mechanism reported in [our and Dr. Shi’s] studies suggests that the special structure of the hairs of the Saharan silver ant could be used as basis for developing novel, highly-reflecting materials.”