Amber fossils trapped ancient insects wearing camo

Loading...

If you want to blend into your environment you might don a shirt, hat, or pants that match your surroundings. But humans aren't alone in dressing to camouflage themselves. Some insects do it, too.

Little bugs cover themselves with bits of plant matter, dirt, and even the exoskeletons of other insects to hide from predators and sneak up on prey.

And scientists just discovered that these insects have been masters of disguise for more than 100 million years.

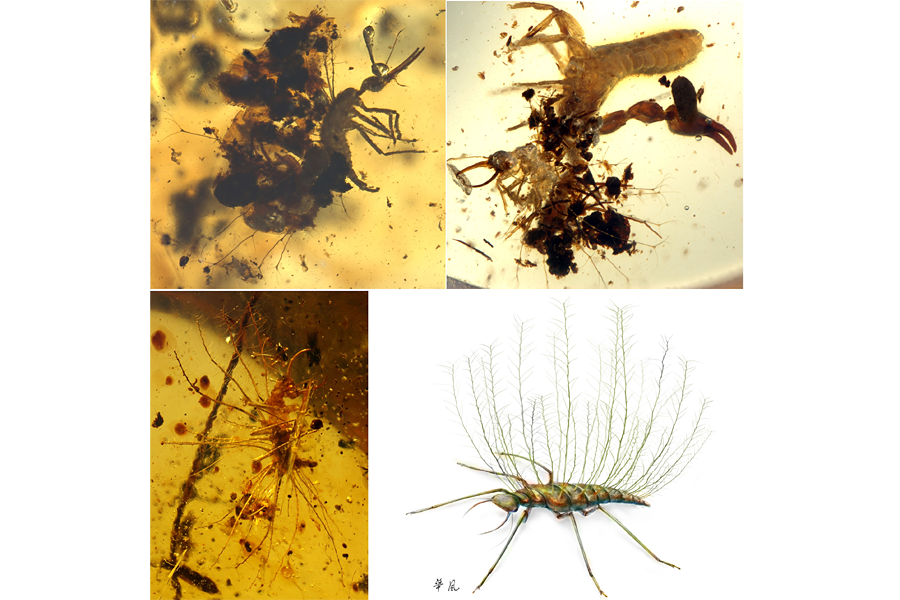

But the insects' camouflage outfits don't protect them from every fate. Some walked or fell into sticky tree resin wearing their self-selected suits. As time passed, that sticky goop hardened and fossilized into amber, freezing the debris-laden insects in time.

Fortunately for scientists, amber fossils preserve the little bits of plant matter, insects' exoskeletons, dirt, and other minuscule particles that other preservation processes do not. So when these chunks of amber made their way into the hands of Bo Wang and his colleagues, they provided the palaeobiologists a detailed snapshot of the camouflaging insects in action, millions of years later.

"Reconstructing the behavior of ancient animals is a challenge to paleontologists because ephemeral events are hardly preserved in the rock," Dr. Wang of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Nanjing explains in an email to The Christian Science Monitor. "But occasionally few fossils document particular behaviors directly. We have some direct evidence of debris-carrying behavior; some fossils are carrying some debris on their back, which are trapped in amber."

Wang and his colleagues hunted through more than 300,000 amber specimens from Myanmar, China, France, and Lebanon in search of insects displaying debris-carrying behavior. They describe 39 specimens in a paper published Friday in the journal Science Advances.

These fossils show this behavior occurred in three distinct groups of insects, Chrysopidae (green lacewings), Myrmeleontoid (split-footed lacewings and owlflies), and Reduviidae (assassin bugs).

Besides one 110-million-year old green lacewing found encased in Spanish amber, the specimens Wang and his team examined are the oldest direct examples of insects displaying debris-carrying camouflage. And the new specimens show that this behavior was well-established by about 130 million years ago.

"These ancient fossils are quite remarkable," George Poinar, an entomologist at Oregon State University known for his research on amber fossils, who was not part of this study, tells the Monitor in an email. And they "show that insect behavior was very similar in the Cretaceous to what it is today. "

These insects carry quite the large load of trash on their backs. And they have an interesting structure to support their camouflage coat.

Some of the insects have long filaments or shorter bristles sticking up off their backs that seems to anchor the debris cloak. This feature generally still appears in the living relatives of those prehistoric specimens with one notable exception.

"Only one group (chrysopoid larvae) exhibits highly setigerous tubular tubercles on the thorax and abdomen, which are no longer seen in extant chrysopoid larvae," Wang says, describing the extremely long filaments growing out of the back of the prehistoric larvae relatives of the green lacewing. "But we do not know why these morphological adaptations are absent in modern counterparts."

"Debris-carrying, a behavior of actively harvesting and carrying exogenous materials, is among the most fascinating and complex behaviors because it requires not only an ability to recognize, collect, and carry materials but also evolutionary adaptations in related morphological characteristics," the authors write in the new paper.

And the need to camouflage must have had strong evolutionary drivers, because, as Wang tells Smithsonian.com, these features "evolved separately in three groups of Cretaceous insects, some of which were later distributed [widely] in the world."

Furthermore, all the specimens described in the new paper are juveniles, larvae. So they must have been learning to create a trash cloak at an early age.

"It is baffling to think that these larvae actually had the ability to carry out this behavior," Dr. Poinar says. "Certainly this behavior requires knowledge and actions that are beyond what we may consider an instinctive response."