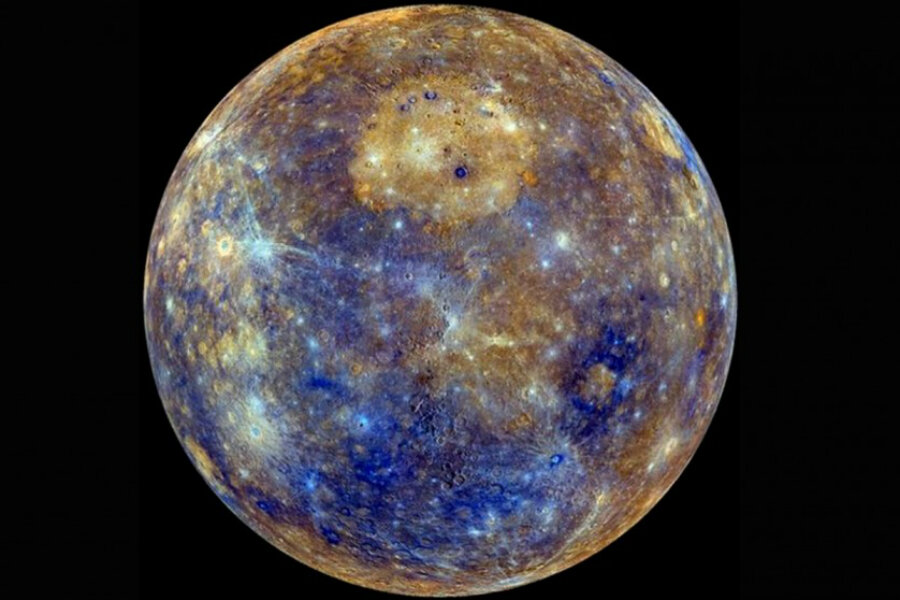

How Mercury's volcanoes fell silent 3.5 billion years ago

Loading...

What made Mercury cool off so early?

A new study, published in July in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, suggests that Mercury stopped spewing lava some 3.5 billion years ago – much earlier than other planets in the solar system. Researchers say their findings could provide new insights into the geological evolution of Mercury and other rocky planets.

“These new results validate 40-year-old predictions about global cooling and contraction shutting off volcanism,” said lead author Paul Byrne in a statement.

Volcanic activity can occur in two different forms: explosive and effusive. Explosive volcanic events, such as the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption, produce powerful bursts of ash and debris. Effusive volcanism is subtler, pouring lava slowly over a wide landscape. The latter type is believed to be an essential step in how planets form crusts.

Using volcanic deposits, researchers can glean information about a planet’s geological background. While the inner planets in our solar system are mostly made of the same materials, the formation timeline varies from planet to planet – Venus stopped experiencing effusive volcanism a few hundred million years ago, while Mars was active just a few million years ago. Earth, as we know, is still an active volcanic site.

Of the inner planets, Mercury is the least explored. This dense, rocky planet spins in close proximity to the Sun, and, as a result, the Sun’s more powerful gravitational force tends to pull objects from Mercury’s weaker orbit. There are no physical samples from Mercury’s surface, and research is mostly limited to flyby data.

NASA’s MESSENGER probe, which launched in 2004 and achieved orbit in 2010, was the second manmade object to observe the planet up-close. Dr. Byrne, a planetary geologist and professor at North Carolina State University, used photographs from the MESSENGER mission to make new inferences about the planet’s little-known geological history.

“On Mercury, there are two basic processes going on: impact bombardment and volcanism,” says co-author Caleb Fassett, a visiting professor of astronomy at Mount Holyoke College, in an interview with The Christian Science Monitor. “The interplay of those processes is very interesting. But there’s strong evidence that many of these plains are volcanic, based on morphology.”

After recording the number and size of craters on the planet’s surface, Byrne and colleagues used mathematical models to approximate the age of effusive volcanic deposits on Mercury. Through this technique, known as crater size-frequency analysis, they found that major volcanic events ceased on the planet around 3.5 billion years ago.

The results appear to confirm long-held hypotheses about planetary cooling.

“Mercury is only about as big as Earth’s moon,” says Dr. Fassett. “We think that planets lose heat more efficiently when they’re small. And Mercury is just a weird place in general – its mantle is very thin compared to its core.”

Rocky planets produce heat through radioactive decay in the mantle. Since Mercury’s mantle is relatively small, researchers say, it makes sense that the planet would lose heat more quickly. Mercury would have contracted in the cooling process, cutting off magma flow to the surface.

“Now that we can account for observations of the volcanic and tectonic properties of Mercury, we have a consistent story for its geological formation and evolution,” said Byrne, “as well as new insight into what happens when planetary bodies cool and contract.”

Researchers say their new study strengthens the notion that Mercury’s evolution ended early. But there are limitations to what can be accomplished through remote data alone.

“There are huge uncertainties about the impact rate because we don’t have samples,” says Fassett. “The holy grail would be a Mercury sample return, but that’s going to be a challenging thing for planetary science.”

In 2015, NASA allowed MESSENGER to crash into Mercury’s surface, having completed a successful 4-year orbit. Astronomers will seek new revelations about the innermost planet from the joint European-Japanese BepiColombo mission, which is scheduled to launch in 2017 and arrive in orbit around Mercury in 2024.

Spaceflight Now describes mankind's second-ever mission to Mercury:

BepiColombo’s transit module will be jettisoned just before it steers into orbit around Mercury on Jan. 1, 2024. The mission’s Japanese and European components — each fully functioning spacecraft — will separate and fly into different orbits for at least one year of observations, looking at the planet’s cratered surface, investigating its origin, probing its interior, examining its tenuous atmosphere, studying its magnetic field, and timing Mercury’s orbit around the sun to test Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

Mercury will fly around the sun four times during BepiColombo’s one-year prime mission. The orbiters should have enough fuel for a one-year extension.