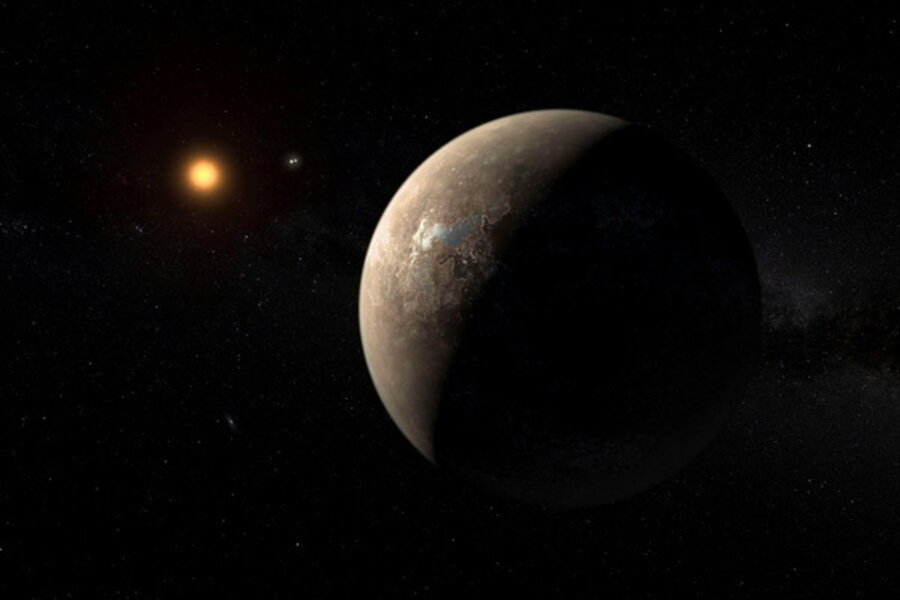

Earth-like schmearthlike: How should we talk about potentially habitable planets?

Last week, astronomers announced the discovery of a “second Earth” not far from our own – except for the fact that it might not be.

Like many exoplanet candidates before it, such as Kepler-452b and Gliese 667 Cc, Proxima Centauri b was described in media coverage as being distinctly “Earthlike.” But in reality, very little is known about our neighbor’s habitability or its atmosphere. What’s more, most of what we do know about the planet seems to contradict epithets such as “second Earth” and “Earth 2.0” – labels which may do a disservice to the general public when misused.

“If we say Earth-like in every press release, it kind of cheapens it in a way,” NASA exoplanet scientist Steve Howell told Mashable.

Proxima b is certainly a good place to look for life. It was found just one star system away from us, orbiting within the habitable zone of its star, Proxima Centauri. It’s even Earth-sized: just 30 percent more massive than Earth, researchers estimate.

But in many other ways, this so-called “second Earth” is quite different from our little blue planet. It takes the Earth about 365.25 days to fully revolve around the Sun. A year on Proxima b is considerably shorter. It completes a full revolution around Proxima Centauri every 11.2 Earth days.

That’s because the planet orbits extremely close to its central star. If Proxima Centauri were as hot as our sun, Proxima b would be burnt to a crisp. Fortunately for anything that may be living there, the star in question is a relatively cool red dwarf, which doesn’t preclude the possibility of nearby Earth analogs.

But there’s still the question of habitability. Using data from the European Southern Observatory, researchers identified Proxima b as potentially life-bearing. That means the planet is neither too hot nor too cold to have liquid water on its surface, and may even have a rocky surface. But this cannot yet be confirmed.

Astronomers have theorized that when planets closely orbit red dwarfs, as Proxima b does, they may become tidally locked. Like the moon to Earth, only one side of the planet would ever face its parent star. The "dark side" would freeze, while the ‘"light side" would be pummeled by solar radiation.

Proxima b’s atmosphere and potential oceans could theoretically redistribute that energy. But even if the planet has an atmosphere, it would probably have been thinned by extreme radiation, producing harsh conditions on the surface.

In other words, while this Earth-sized planet could be habitable, it probably isn’t Earthlike. But does the distinction matter?

Imprecise labels have the capacity to mislead. To the average person, “Earth 2.0” may convey green grass or deep blue oceans. And the overuse of such terms can tire readers, sapping the public excitement that both astronomers and media hoped to kindle.

But it may not be so long until we find a true Earth 2.0. New telescope arrays are being built on every corner of the world. These observatories will be capable of viewing the universe with increasing clarity. Some, like NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, will scour space for biosignatures like oxygen. And when those technologies become available, Proxima b will be a great place to start using them.