What 63 newfound quasars might tell us about the early universe

Quasars are among the oldest – and brightest – objects in the observable universe. But because these objects are located at the farthest reaches of the universe, scientists have seen precious few.

But on Monday, astronomers from the Carnegie Institution for Science doubled that number. Using high-powered telescopes, they discovered 60 new quasars, each more than 12 billion years old. The team’s research, which could yield new insight about how the universe emerged from its “dark ages,” will be published in the next edition of the Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series.

“The formation and evolution of the earliest light sources and structures in the universe is one of the greatest mysteries in astronomy,” lead author Eduardo Bañados, a research fellow at the Carnegie Institution, said in a statement. “Very bright quasars such as the 63 discovered in this study are the best tools for helping us probe the early universe. But until now, conclusive results have been limited by the very small sample size of ancient quasars.”

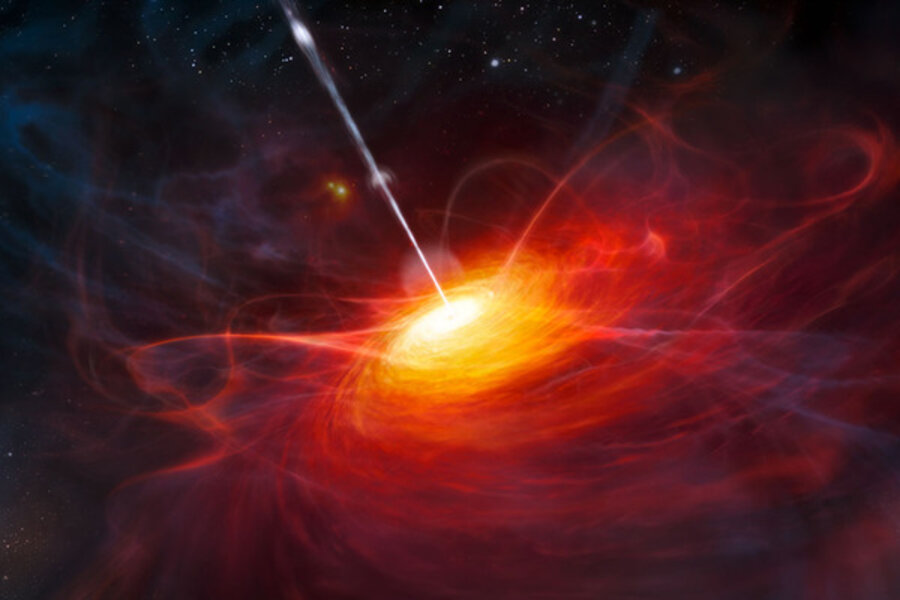

At the center of many distant galaxies, supermassive black holes gobble up heaps of cosmic matter. Just on the periphery of these black holes, luminous “galactic nuclei” called quasars can be found. These objects can be 100 times brighter than our own galaxy.

“Quasars are among the brightest objects and they literally illuminate our knowledge of the early universe,” Dr. Bañados said.

But in the 50 years since the first quasars were detected by radio technology, precious few have been identified. It’s a big deal in the astronomical community when even one is found – the discovery of a distant quasar, SDSS J0100+2802, made headlines in 2015 for the insights it led to regarding the growth of supermassive black holes.

But Bañados and colleagues didn’t find just one quasar, or even 10. They found 63.

The find, researchers say, could accelerate our understanding of the early universe. According to prevailing theories, the universe began some 13.8 billion years ago with an outward explosion of matter – a Big Bang. For a few hundred thousand years, hydrogen ions and other subatomic particles formed a massive scorching cloud. When it finally cooled, the universe entered an era of “recombination,” wherein those particles formed atoms. And then, everything went dark.

Scientists theorize that 500 million years after the Big Bang, the “dark ages” came to an end with the birth of the first stars. Radiation from those stars re-ionized hydrogen, which allowed for the formation of heavy elements and essentially turned the lights back on.

Quasars, like the ones described by Bañados and colleagues, may be ancient remnants of this transition. With new subjects to work from, researchers may have a new window into that crucial cosmic moment.