After more than a decade, Rosetta space probe makes its final landing

Loading...

| BERLIN, GERMANY

Scientists began saying their final farewells to the Rosetta space probe Thursday, hours before its planned crash-landing on a comet, but said that data collected during the mission would provide discoveries for many years to come.

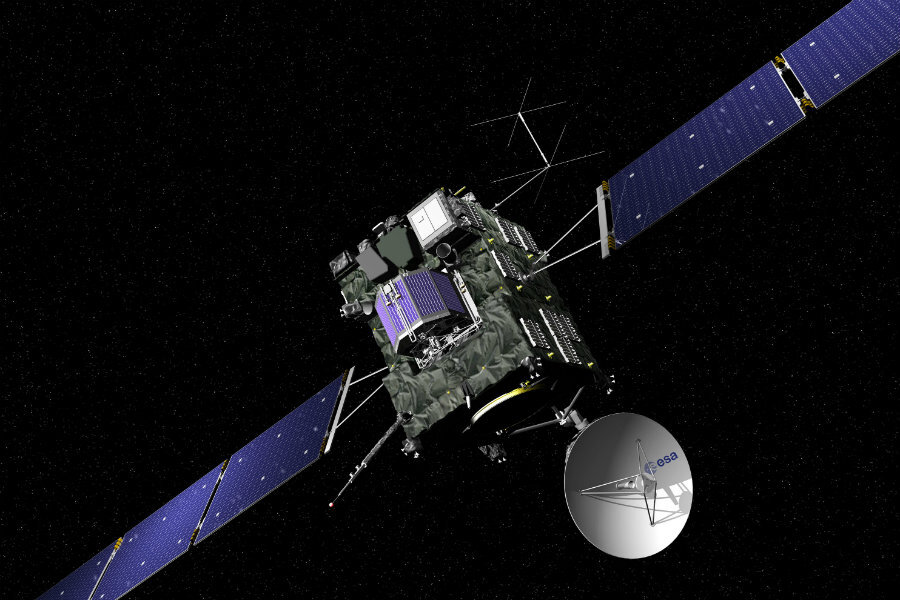

The spacecraft, launched in 2004, took a decade to reach comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, where it released a smaller probe called Philae that performed the first comet landing in November 2014.

With almost two dozen scientific instruments between them, Rosetta and its lander gathered a wealth of data about 67P that have already given researchers significant new insights into the composition of comets and the formation of celestial bodies.

"The best thing is we still haven't gone through all our data," said Mohamed El-Maarry, a researcher at the University of Bern, Switzerland.

El-Maarry said OSIRIS, the main camera on board the probe, had captured some 80,000 images, many of which have yet to be analyzed fully.

A few more will be added during Rosetta's final hours, as the European Space Agency steers the probe toward the comet so it can take unprecedented close-up images before colliding with the icy surface.

Other instruments were used to 'sniff' for molecules on the comet and examine its insides with radar. Among the key findings was the discovery of molecular oxygen on the comet, forcing scientists to reconsider previous assumptions guiding the search for alien life.

The mission also found that the type of water on 67P is different from that on Earth. This challenges the idea that the bulk of the water on our planet was "delivered" by comets crashing into it.

"Gaining knowledge is not always about finding answers to questions," said Bjorn Davidsson, who works at the California Institute of Technology's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena. "The first step of knowledge is to start to ask the right questions. So maybe that is the step we are in now, that we are finally starting to understand the problems so much that we start to ask the right questions."

However, the notion that comets can serve as cosmic chemistry labs capable of creating the building blocks for life – and seeding them on Earth – received a boost from discoveries made during the Rosetta mission.

Philae has helped dispel preconceptions about comets and "captur[ed] the attention of the world," Markus Bauer, of the European Space Agency, told The Christian Science Monitor in February:

“We have learned a lot about comets,” continues Mr. Bauer. “We had to learn for example that the water on comets is not the same water as in Earth's oceans. Our water must therefore have come from other sources.

“We have discovered organic compounds which play a key role in the prebiotic synthesis of amino acids and sugars, which are the ingredients for life.”

And, as [Manuela] Braun of DLR explains, “We expected a comet’s surface as soft and fluffy – but learned that it could be very heterogenous. The place where Philae finally came to rest has a very hard surface.”

Kathrin Altwegg, who heads the team cataloguing the comet's chemical composition, said scientists also expect to be able to say soon whether rare elements such as the noble gas xenon were brought to Earth by comets.

"Analysis is ongoing," told an audience at the European Space Agency's mission control in Darmstadt, Germany. "In the next two months, we will have the results."

By then the comet will be more than 730 million kilometers (454 million miles) from Earth with two man-made probes on its surface – assuming that Rosetta's final maneuver goes according to plan.

Scientists decided to crash-land the probe on the comet because its solar panels won't be able to collect enough energy to power Rosetta as it hurtles away from the Sun along 67P's elliptical orbit.

Although the European Space Agency has promoted the mission to the public using cartoons , music and social media , it won't be dwelling on the moment that Rosetta hits the surface Friday about 1040 GMT (6:40 a.m. EDT) .

"As soon as we impact we lose the signal, and that's the end of Rosetta," said Matt Taylor, the project scientist. "It's all about the bit beforehand. Rosetta wasn't designed to land."