Asgardia, first ‘nation in space,’ seeks UN recognition

Loading...

In Norse mythology, Asgard is the realm of the gods. From the central palace of Valhalla, Odin, Thor, Loki, and the rest of the pantheon look down at the Earth and its inhabitants.

It is this image that Russian businessman and scientist Igor Ashurbeyli hoped to evoke as he laid out his plans for "Asgardia," the first "nation in space," in a speech in Paris on Wednesday.

Dr. Ashurbeyli hopes to secure UN recognition for Asgardia, a nation of scientific exploration free of geopolitical restrictions. The somewhat vague but lofty ideals of the project have many people asking whether such a goal is possible, and what its implications might be.

According to the project's website, Asgardia will provide a platform to "demonstrate to scientists throughout the world that independent, private, and unrestricted research is possible" in space. The site provides users with a chance to register as a "citizen" of Asgardia.

"The essence of Asgardia is peace in space and the prevention of Earth’s conflicts being transferred into space," said Ashurbeyli in his speech. "Asgardia is also unique from a philosophical aspect – to serve entire humanity and each and everyone, regardless of his or her personal welfare and the prosperity of the country where they happened to be born."

The premise may seem like science fiction, but Ashurbeyli, who founded the Aerospace International Research Center in 2013 and is the current chairman of UNESCO’s Science of Space committee, hopes that Asgardia could get legal recognition from the UN as an independent nation.

"Physically, the citizens of that nation state will be on Earth; they will be living in different countries on Earth, so they will be a citizen of their own country and at the same time they will be citizens of Asgardia," he told The Guardian, speaking through an interpreter. "When the number of those applications goes above 100,000, we can officially apply to the UN for the status of state."

While Asgardia's site shows that the nation is well on its way to 100,000 "citizens," that might not be enough for the UN to accept Asgardia as a legitimate entity.

"A state in the classical sense has a territory and has a significant portion of its population living on that territory," Frans von der Dunk, a professor of Space Law at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, told Popular Science. "As long as nobody's going into space, you can have as many signatures as you want, but you are not a state."

There are no plans to send citizens of Asgardia into space to acquire "territory," though the organization did release a statement saying that there would be a launch of an Asgardian satellite sometime in the autumn of 2017.

Dr. von der Dunk pointed out that a "nation," as Asgardia refers to itself on the website, might be more accurate descriptor than "state." "Nation" refers to a group of people who share a common history, religion, ethnic identity, or another common bond. For instance, the Kurds in the Middle East are often referred to as having a national identity, since they have a common culture, language, and even geographic areas with a majority population. However, since they do not have an independent government, they cannot be said to be a "state."

It is hard to say whether Asgardia, now only a day old, could receive the same kind of recognition as traditional nations with cultures that span centuries.

In theory, Asgardia could also function as a workaround of international space law. In 1967, the Outer Space Treaty (OST) was ratified by 104 nations in an effort to prevent space-based war. According to the OST, no country can claim or occupy any celestial body, and exploration of space has to benefit all humankind, not just one nation. But OST has its challenges too, as The Christian Science Monitor's Lonnie Shekhtman reported in an article about corporate interest in Mars:

Just last year, the US challenged that decree [the OST] when President Obama signed a law allowing American companies to mine asteroids for commercial purposes.

SpaceX is not a country, so it’s unclear whether the international law would apply if it landed on Mars first. Already this ostensible treaty loophole has been exploited. Dennis Hope, a Nevada man, has sold parcels of land on the moon and other planets to nearly 4 million people through his extraterrestrial real estate company Lunar Embassy, according to a 2009 National Geographic report. Mr. Hope claims the OST doesn’t apply to individuals, though the United Nations says it does.

It is impossible to say how exactly Asgardia would fit into the OST.

"There are formidable obstacles in international space law for them to overcome," Christopher Newman, an expert in space law at the UK’s University of Sunderland told the Guardian. "What they are actually advocating is a complete re-visitation of the current space law framework."

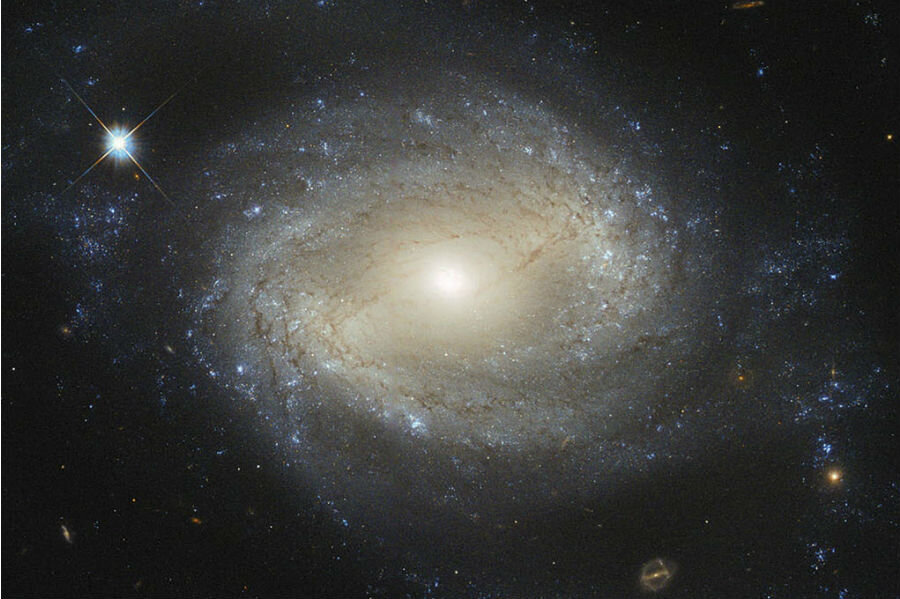

In addition to hitting the reset button on Cold War-era space treaties, Asgardia also hopes to promote defense of the Earth against potentially destructive meteors and other objects in the night sky.