Native American family tree sprouts a new branch

Loading...

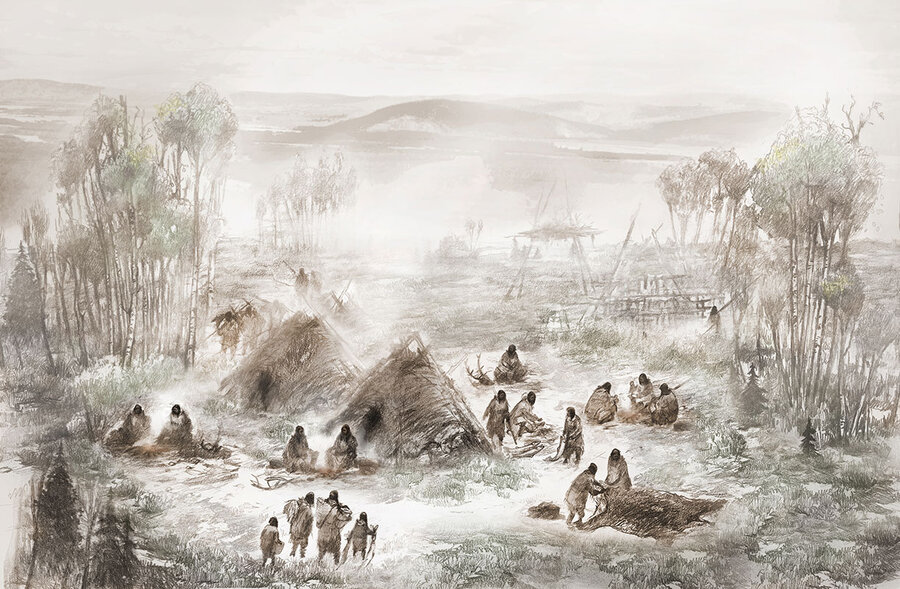

A six-week old infant who died some 11,500 years ago in central Alaska is now providing clues about how the Americas first came to be populated.

Genomic data from remains of the girl – named “Xach'itee'aanenh T'eede Gaay” (Sunrise Girl-Child) by the local indigenous community – broadly support a migration model that scientists have long argued for, while also revealing the existence of an ancient population previously unknown to science.

“We’ve said for decades that the first Americans came from Northeast Asia to the Americas during the late Pleistocene, but the empirical evidence for that has not been at our fingertips as it is now,” says Ted Goebel, an anthropologist at Texas A&M University in College Station, who was not involved with the study. “To finally start to see the genomic evidence come forth to help us test these theories we’ve developed based on stone tools is really cool."

The girl was a member of an ancient population that the report authors have named “Ancient Beringians.” Beringia is the name given to Alaska, Eastern Siberia, and the land bridge that periodically connected the two during the last ice age.

The findings suggest a revised family tree: a single ancestral Native American group split from East Asians about 35,000 years ago, before later splitting, some 20,000 years ago, into two distinct groups. One was the Ancient Beringians, and the other constituted the ancestors of modern-day Native Americans, who later split into northern and southern populations about 15,700 years ago.

“Trying to integrate these findings with what we know from archaeology and paleoecology presents exciting new puzzles,” says Ben Potter, an anthropologist at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks and one of the lead authors of the study, which was published Jan. 3 in the journal Nature. He first discovered the archaeological site in 2006 and has been working there ever since. “The peopling has been shown now to be more complex than we thought previously.”

Scientists have sought ancient human remains from Beringia at the end of the last ice age, says Victor Moreno-Mayar, a geneticist at the Centre for GeoGenetics at the University of Copenhagen’s Natural History Museum of Denmark, who conducted much of the genetics work for the study. The discovery of three individuals, one of them cremated, fulfilled this wish.

But Xach'itee'aanenh T'eede Gaay's genome held a surprise: it was clearly Native American, but not from either of the two major modern Native American groups. “It represented a population that diverged from that common ancestor,” says Dr. Moreno-Mayar.

All of this helps narrow down and strengthen the theories of just how those populations arrived in the Americas. It also lends support to the so-called “Beringian standstill” hypothesis, which posits that there was a period of time in which a genetic isolation of ancestral Native Americans occurred before they migrated south, either in Beringia or in Northeast Asia.

But mysteries remain, including definitive answers about where and when some of these population splits occurred and which migration routes were used.

In their paper, the authors outline two possible models. In one scenario, which Dr. Potter favors since it matches well with archaeological data and paleoecological data, the split occurred in Northeast Asia, and the two separate populations later crossed over the land bridge prior to 15,700 years ago, when the Native American ancestors split again. With the ice age still at its maximum around 20,000 years ago, Potter notes that any further migration would have been difficult.

In the other theory, the ancestral population had already arrived in Alaska or eastern Beringia by 20,000 years ago, and the split occurred there, with the second split into North and South American populations occurring south of the ice sheets.

What happened to the Ancient Beringians? They might have died out, says Potter, or they could have been absorbed by Northern Native Americans who migrated back to the far North.

Dr. Goebel likens the puzzle to a murder mystery. “You read the book, and the author divulges new clues over the course of the book,” he says. “Every time a new genome is analyzed and reported, it provides a new clue that’s making the pathway to uncover the real story that much clearer.”