The paradox of 'code'

Loading...

There’s a four-letter word I keep running into, and this week I’ve finally decided to look into it. No, I’m not going to get into anything rude here. And for what it’s worth, unlike most of the words we mean when we say “four-letter word,” this one is of Latin origin, not Anglo-Saxon.

The word is code. Its first definition as a noun in the Oxford English Dictionary, labeled “Roman Law,” reads, “One of the various systematic collections of statutes made by later emperors,” such as Justinian’s code.

Its first cited use is in the enticingly titled work “Handlyng Synne,” by poet and historian Robert Manning, in 1303.

Code came from the Latin codex, in turn a variant on caudex. The original meaning of that word was “the trunk of a tree.” From there codex was extended to mean wooden tablet, book, or specifically, a code of laws.

The idea behind a “code” is to compile, or bundle, a lot of disparate bits of legislation into a single volume, or series of volumes, where they are more or less freely accessible, in libraries or, today, online.

I’ve been running into the “U.S. Code” frequently in a book I’ve been working on. A law will be known as, say, the Administrative Procedure Act (1946), and have a further tag as Public Law 79-404 – indicating that it was the 404th piece of legislation to pop out of the sausage mill of the 79th Congress (1945-47). But it will be “codified,” as the expression goes, as, in this instance, U.S. Code Vol. 5, Sec. 500–596 (2012).

From 1804, we have the Code Napoléon – another compilation of laws from another emperor.

But during the 19th century, code expanded from a strictly legal meaning to “a system or collection of rules or regulations on any subject.” Oxford cites a reference from Samuel Taylor Coleridge: “In the legislative as in the religious Code.”

The sense of “code of honour” arose about this time.

The 19th century also saw the rise of code to mean “a system of words arbitrarily used for other words or for phrases, to secure brevity and secrecy.”

In the days of paying by the word for one’s messages, people learned to use code to save on the cost of their telegrams.

That must be what the Pall Mall Gazette was getting at when it reported, in 1884, “Telegraph companies had to face ... the extension of the use of code words.” It sounds like the annoyance today’s television advertisers face when viewers TiVo past their commercials, or catch all the good parts on YouTube, doesn’t it?

As a verb, code goes back to the early 19th century – but Oxford’s examples sound very contemporary. Here’s one from 1815: “Robbery ... Is sternly coded as a deadly crime.”

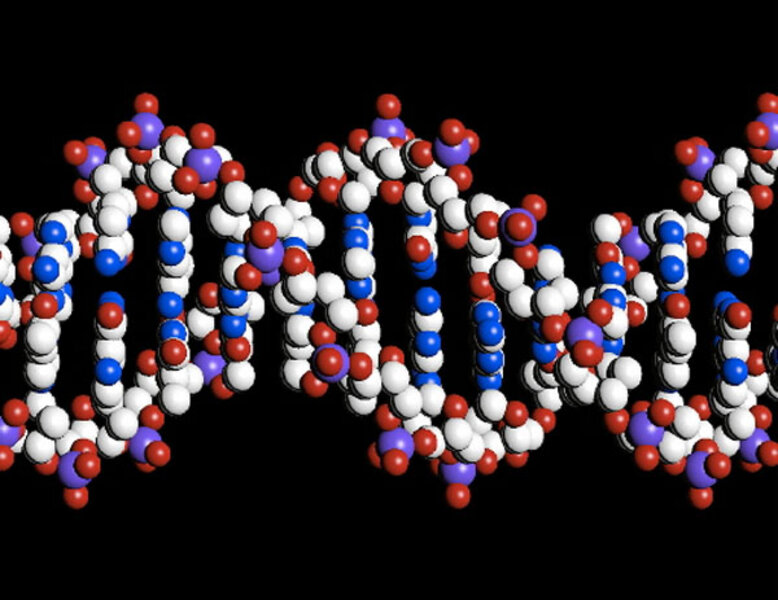

The computing sense of code goes back to the 1940s. Genetic code, which builds metaphorically on the idea of “instructions for a machine,” with man as the machine, made its appearance in 1961, according to Merriam-Webster.

Today, that dictionary gives a couple of definitions for code as a verb that would appear to be mutually contradictory: “to put (a message) into the form of a code so that it can be kept secret” and also “to mark (something) with a code so that it can be identified.”

This is the paradox of code: It refers both to ways of making things secret and to ways of making things known.