DNSChanger cutoff is more whimper than bang. Score one for the good guys.

Loading...

Do more than 200,000 computer users worldwide make any sound if they can't connect to the Internet? Apparently not – or not much, anyway.

Despite a slew of hyperbolic headlines proclaiming Sunday at midnight to be an "Internet doomsday," the clock struck 12 and … there was no massive digital meltdown. (Although there may have been some emotional outcries that carried only as far as home-office walls.)

At least one cybersecurity executive is hailing the lack of resulting drama Monday as a “victory of shared collective intelligence.”

The non-catastrophe unfolded when, as expected, computer servers that for eight months had supplied malware-infected computers worldwide with a temporary Internet connection, were finally shut down Sunday night following a federal judge's order.

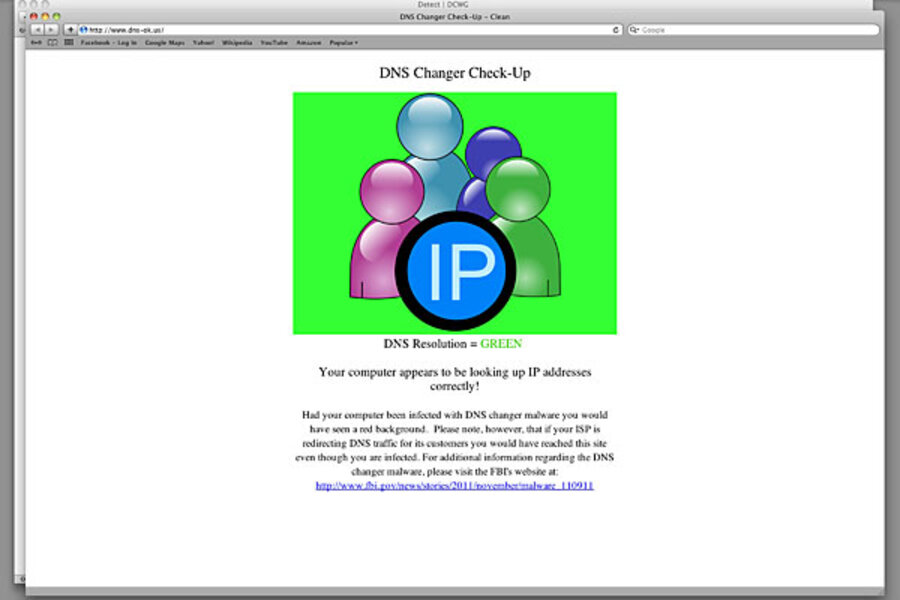

During those eight months, Google, Facebook, the FBI, Internet service providers (ISPs), and others had bombarded some 4 million computer users worldwide with e-mails and other notices warning them that their machines were infected with a nasty trojan called the DNSChanger.

Apparently that public information campaigned worked pretty well. By late last month, just 250,000 computers worldwide remained infected with DNSChanger, the creation of a cybergang bent on defrauding Internet advertisers.

Even so, as of Sunday night just before the cutoff, 210,851 computers and routers worldwide still remained infected with DNSChanger, among them 41,557 computers and routers in the US. All seemed bound to have the plug pulled on their Internet service.

But, while some users doubtless felt the axe fall – others saw their ISPs step into the breach after the FBI cut off access. Spokesmen for AT&T and Verizon both told PCWorld magazine the companies had stepped in to keep on supplying service – the former through the end of the year, the latter through the end of July – giving infected-computer users yet another break.

Instead of returning home from work Monday to discover they cannot update Facebook or download cute puppy videos, many users of the 41,000 affected US computers will as a result still be able to connect to the Internet for a while longer – another chance to clean up their infected machines.

For cybersecurity experts and the FBI, though, the muted sound is bliss – it means that most of the problem had been cleaned up in advance without a major implosion.

"We've seen a kind of a victory of shared collective intelligence in this case," says Rod Rasmussen, president of Tacoma, Wash.-based Internet Identity, a cybersecurity firm that is part of the law-enforcement-backed DNSChanger Working Group consortium. "A lot has been learned by law enforcement and private companies about how to work together to bring down these criminal enterprises – but also how to remediate the problem over time, rather putting a lot of people in the dark all at once."

It also represents, he and others say, a sign that government and law enforcement – supported by technicians in private industry – are increasingly able to initiate complex international cybercriminal investigations that span international borders.

"There's definitely a trend with government more willing to get involved to fight botnets like the DNSChanger and other malware – in addition to using the legal system to take down servers used by criminals," says Brett Stone-Gross, a senior security researcher with Dell SecureWorks.

In a parallel example earlier this year, the FBI along with private industry worked to notify thousands of computer users whose machines were infected with the Coreflood trojan, a piece of malware that stole proprietary information from personal computers worldwide and enslaved them into a giant botnet.

As part of that trend, takedowns of botnets have been occurring with growing speed in the US, Britain, Spain, and a handful of other countries, Mr. Stone-Gross says.

Still, some Internet wags were already comparing the DNSChanger trojan takedown to the Y2K hyperbole – noting that not much has really happened after all.

But that is not really correct, these experts say, since a very real effect – if not a very loud one – can be seen by security researchers: namely, more than 200,000 machines worldwide infected with the DNSChanger now dropping off the Internet.

One reason researchers can observe the infected machines at all is that the very servers that had been supplying Internet addresses to the infected machines – were not actually shut down Sunday night at all, but only instructed not to respond to the infected machines anymore. In the interest of learning, researchers are now observing the remaining DNSChanger-infected machines worldwide try to connect, fail, try again – and then stop communicating.

One odd tidbit. Some machines running older versions of the Windows operating system had a backup feature that allow those machines to try to connect to the Internet using a backup system. It's not clear yet how many of those machines will be able to resurrect themselves. For most owners of infected computers, however, the only recourse after getting cut off will be to take their machines into a shop for repair.

"So far the pattern is what we expected, a big drop off in connection attempts," Mr. Rasmussen says. "Some machines are still trying and failing to connect to the servers. We've instructed the servers not to respond. It's tough love, I guess. Tonight, just before midnight, we will actually, finally pull the plug."