Obama plan for high-speed rail, after hitting a bump, chugs forward again

Loading...

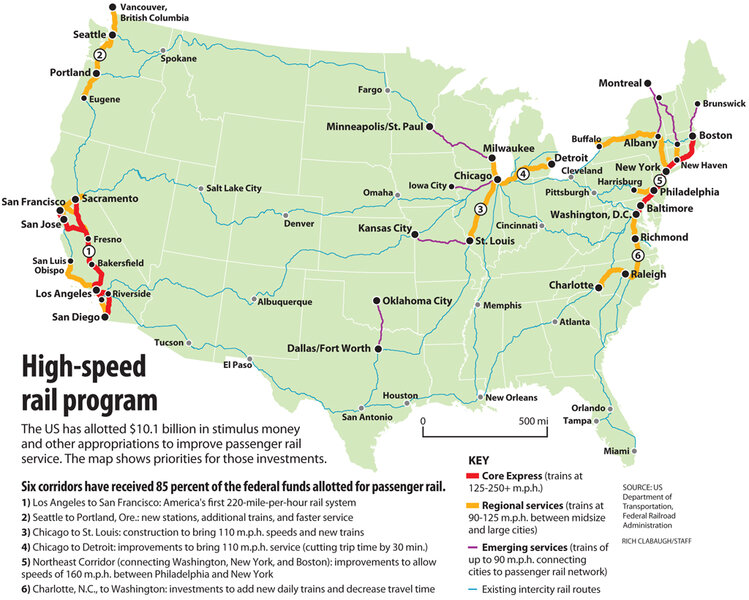

President Obama's vision of bullet trains whizzing through the California countryside, and from Boston to Washington, D.C., at 220 miles per hour is still alive, though with many fewer bells and whistles.

Just a few months ago, the program seemed moribund – or headed that way fast. First, Republican governors in Florida, Ohio, and Wisconsin early last year rejected federal dollars and high-speed rail plans for their states, citing their expectations for cost overruns and insufficient ridership. Then, in November, Congress axed the White House's six-year, $53 billion budget request for high-speed rail. Critics celebrated, with the conservative National Review proclaiming in a headline, "The Death of a High-Speed-Rail Program."

But the Obama plan to build high-speed rail corridors, conceived in 2009 and intended to catch America up to the sophisticated passenger rail systems in Asia and Europe, has lately been revived by two turns of events. First, in June, Amtrak unveiled a $150 billion upgrade plan for the Northeast rail corridor that stretches from Boston to Washington, D.C. – with new high-speed rail service as its centerpiece. Then, California's Legislature voted July 6 to approve $5.8 billion to begin building a new 220 m.p.h. line, starting in the state's Central Valley.

The recalibration marks a big step backward from the original White House plan for 13 high-speed rail corridors in 31 states. California and the Northeast are the only two truly high-speed corridors that remain on the drawing board – with a raft of much smaller "higher-speed" rail improvements in the pipeline.

But even this pared-down plan could, over time, spur expansion of high-speed rail into the Midwest and elsewhere, say advocates of the service. In addition to California and the Northeast, faster trains and other improvements to passenger rail are slated for corridors running from Portland, Ore., to Vancouver, British Columbia; from St. Louis to Chicago; and from Washington, D.C., to Charlotte, N.C.

"It's a foundation that's being laid," says Eric Peterson, a transportation policy consultant and research associate with the Mineta Transportation Institute at San Jose State University. "All this progress is going on despite this national political overlay of apparent total opposition toward anything having to do with passenger rail."

Still, Congress is not authorizing any new money for high-speed rail, and Mr. Peterson says "it may be a year or two" before that happens. "But what people don't realize," he says, "is that there's still money in the pipeline that will push this forward for years."

Congressional hatchets did not touch most of the $10 billion allotted, under the 2009 economic stimulus act, for high-speed rail and "higher performance" rail (with trains that travel 90 to 110 m.p.h.). They mainly slashed future funding. As a result, 153 projects are now swinging into action with $9.6 billion in funding, the Federal Railroad Administration reports.

"We are definitely making progress implementing high-speed rail in America's mega-regions – on the coasts – where 80 percent of Americans live," says Darnell Grisby, director of policy development and research at the American Public Transportation Association (APTA), a Washington-based trade group championing high-speed rail. "We're only just now really ramping up for actual construction projects."

So far, about $1.5 billion of the $9.6 billion has been spent – with another $7.5 billion to be expended by 2017 on projects ranging from tunnel expansion in the Northeast Corridor to upgraded tracks between Portland and Seattle. About 20,000 short- and long-term jobs are created per $1 billion spent – or about 180,000 direct jobs overall.

In 2010, an APTA-commissioned survey of more than 24,000 Americans found that 62 percent would definitely or probably use high-speed rail service for leisure or business travel if it were an option. Since then, however, the public mood may have soured: With the economy still struggling, voter support of high-speed rail in California has faded, a poll in that state found.

"Obviously it's been a rocky start," says Robert Yaro, president of the Regional Plan Association, a New York-based group, and co-chairman of America 2050, which has also supported the national high-speed rail plan. "We have to remember that these huge infrastructure projects can take a generation to win public support."

Critics, though, say high-speed rail will never win broad public backing because it's an expensive boondoggle that would mainly transport the well-heeled in Democratic-voting states – not the average American. They cite studies based on US metro-rail systems, many of which show lagging levels of ridership and revenue. The more pressing need, some say, is to upgrade the links between suburbs, where most people live, with the cities to which people commute.

They also argue that the plan delivers mostly old technology, not true high-speed rail.

"The problem with Obama's high-speed rail is that it's an obsolete technology that doesn't make sense today," says Randal O'Toole, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank that, along with the Heritage Foundation and the Reason Foundation, led the fight to nix the rail plan. And just because it works in other countries does not mean the United States should automatically climb on board.

"High-speed rail was successful in Japan because at the time it was developed only 12 percent of Japanese were driving," he says. "It makes no sense today when cars go where you want to go when you want to go. Just because other countries built this and are driving themselves into bankruptcy doesn't mean we should."

The APTA's Peterson acknowledges that the original Obama plan was "overstated" in terms of what it would deliver, glossing over the fact that many changes would be upgrades, but not bullet trains. That gave opponents an opening to attack it as a lot of spending on outmoded technology, he says. Countries with true high-speed service, he adds, have seen economic gain in the form of transportation efficiency and revitalized city centers.

Not all Republicans in Congress flatly reject high-speed rail. Rep. John Mica of Florida is a sharp critic of the Obama plan, but he is a booster of intercity rail. He also supports high-speed rail in the Northeast, but only if Amtrak hands over the reins to private companies. Other GOP backers are said to include Sens. Mark Kirk of Illinois and Rob Portman of Ohio.

But the huge expense of building high-speed rail – plus the fact that it is largely taxpayer-funded and government-run – makes it a natural target for today's conservatives, in particular. Many say it's dubious that high-speed rail can overcome such political opposition long enough to become viable.

Others, though, note that other big infrastructure projects have overcome such resistance.

"President Eisenhower backed the federal Interstate [Highway] System over opposition of his own party," says Mr. Yaro of America 2050. "But it's very hard to find anyone today that feels that way.... High-speed rail will be the same. It's what we need to create the capacity for national growth for decades to come. The only question is whether we'll see this. I think we can. I hope so."