Why many students might not be choosing 'right' college

Loading...

Had Alexis Calatayud known more about her college options four years ago, things might have been different.

A Miami native from a middle-income family, Ms. Calatayud set her sights early on Florida International University, a local public research institution, dismissing most other options as beyond her price range. Paying extra to live away from home, she says, was something she and many of her peers, who are in similar or worse situations, were reluctant to do.

“We go to FIU because it makes sense economically. It makes sense not to have to pay for room and board,” she says. “I didn’t know what my options were.”

That sentiment – “I didn’t know” – is at the root of a wave of initiatives, rolled out over the past few years by both the government and nonprofits, to connect students to the best college options by removing as many fiscal and informational barriers to enrollment as possible.

Driven by new technology and now-available data, these efforts – which range from financial aid calculators to text services that remind students of upcoming deadlines – aim to kick up college enrollment rates, especially among high-performing students from low-income families.

In the long run, such initiatives could reduce lost opportunities for students and also reap economic benefits for the country, experts say.

“There are students ready for college who decide not to apply, or who get in and decide not to attend, because they may not be aware they qualify for aid. Or they may be aware aid exists but find the process of applying cumbersome,” says Benjamin Castleman, an assistant professor of education and public policy at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Presenting students with the full range of their options and providing support during “critical junctures” in their road to college could make a significant impact in their decision to enroll, he says – something that a number of studies have shown, at least on a small scale.

“One of the biggest barriers is [students] don’t know their options,” says Calatayud, now a senior majoring in political science at FIU and president of the student government. “They just pick price tags.”

Seeking solutions

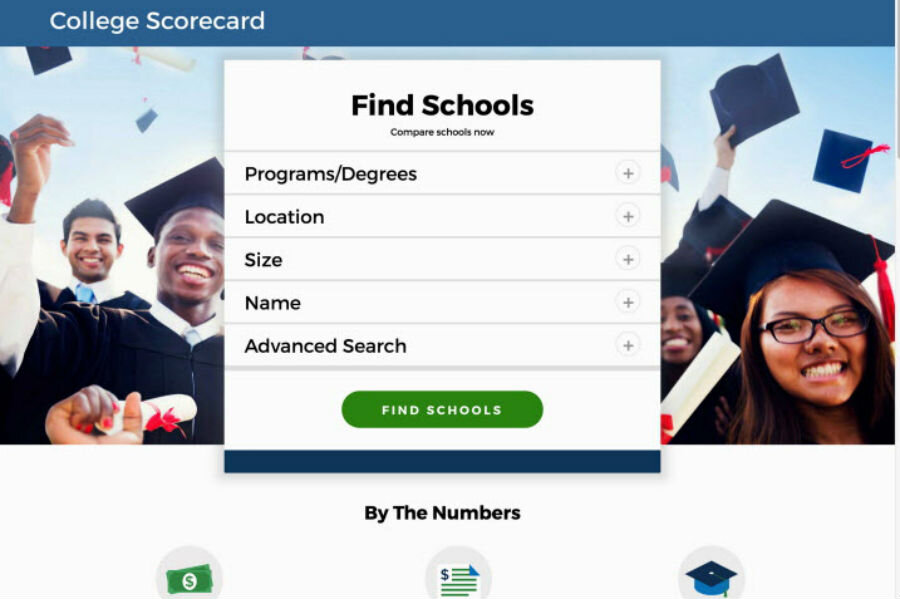

This month, the Obama administration introduced a revamped College Scorecard, meant to help prospective college students identify which schools maximize tuition price, and announced an effort to simplify the process of applying for federal student aid.

On Monday, a group of 80 leading colleges and universities unveiled a plan to develop a free platform of online tools to improve the college admission application process for all students.

And at the 20th anniversary conference of the National College Access Network (NCAN) this week, the nonprofit corporation ECMC Group launched the Pell Abacus, an online, mobile-friendly service that compares costs between colleges for students who qualify for free or reduced lunch – without requiring them to visit each institution’s website or asking them complicated questions about their parents’ tax or income information.

“[W]e’re removing some of the key barriers preventing low-income students from exploring their full range of college options,” said Abigail Seldin, vice president of Innovation & Product Management at ECMC, in a statement.

“Institutions don’t always put their net price calculators in easy-to-find pages on their website,” adds Carrie Warick, director of policy and partnerships at NCAN. “This is a great tool to help give students a more accurate idea of what college will cost.”

From 2011-12, about 2 million students who would have qualified for a federal Pell Grant – which the government awards to undergraduates with financial need – never even applied, according to an analysis by student financial aid expert Mark Kantrowitz, who publishes Edvisors.

Many of these students said they assumed they were ineligible, did not know how to apply, or thought the forms involved were too much work, Mr. Kantrowitz found.

At the same time, more than a fifth of high-performing, low-income students never go to college, compared to only 5 percent of higher-income students at the same achievement level, according to a report released last year by the Education Trust, which advocates for low-income students. A 30 percent college enrollment gap exists between high- and low-income students in the US – a figure relatively unchanged since 1975, according to the National Center for Education Statistics in Washington.

“These very smart, very poor kids … are not applying to college,” says Harold Levy, executive director of the Virginia-based Jack Kent Cooke Foundation, an independent organization that provides scholarships to high-achieving students from the lowest income brackets. “That is a loss for the country, and a profound unfairness to these kids.”

'That might have changed my life'

Calatayud, the FIU student, notes that a better knowledge of what her choices were could have made a significant difference. “I love my institution, but what if I could have found another option for less cost and in the field I specialize in?” she says. “That might have changed my life.”

She adds that, as a second-generation college student, she received ample support from her parents during her application process. “But for so many students, you have to figure it out yourself,” she says. “This resource changes so many things.”

While efforts to reduce information barriers are undoubtedly helpful, they don’t address the real problem when it comes to college access: cost, says Sara Goldrick-Rab, a professor of educational studies and sociology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“These tools are nudges… [but] they don’t make college cheaper,” she says. At the end of the day, “this is about cash. There is no substitute.”

She adds that it will take time before anyone sees the larger, long-term effects of these efforts. "I'll take the small wins where I can get it," Professor Goldrick-Rab says, "but we have to be careful not to pat ourselves on the back too much yet."

For real change to take place, there’s also a need to create a broader college-going culture in schools, so that students are encouraged to maximize their potential and explore their options at every step of the educational pipeline, says Eboni Zamani-Gallaher, a professor of higher education and community college leadership at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

“Simplifying the process is a good thing. Any efforts to make it easier is a good thing,” she says. “But we still have a ways to go.”