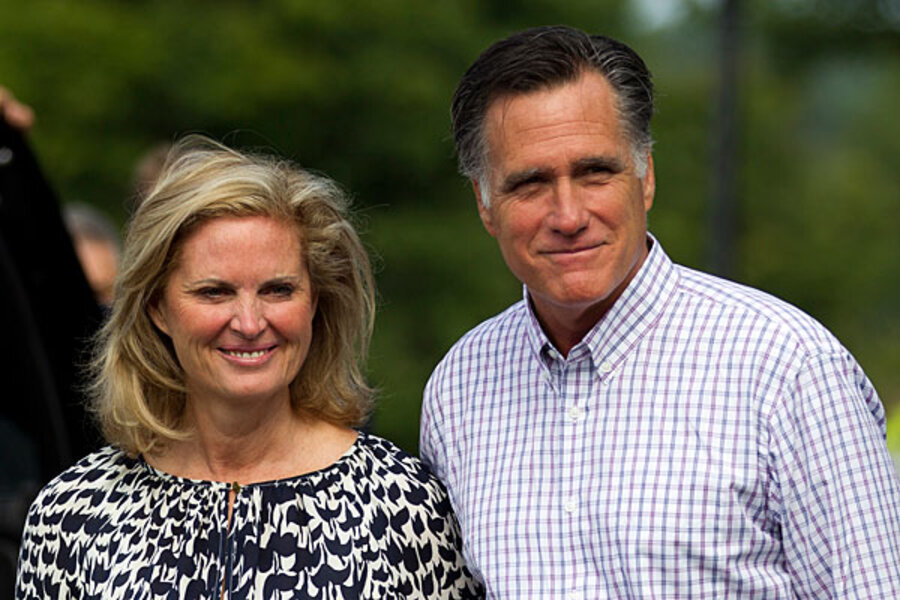

Ann Romney: an enigmatic first lady-in-waiting

Loading...

Don’t underestimate Ann Romney.

The basic facts of Mrs. Romney’s life – a wealthy childhood; years as a stay-at-home mother to five sons in lieu of a career; a passionate interest in the expensive sport of dressage horseback riding – can convey an impression that those who know her say is at odds with the reality.

The relatively conventional, privileged veneer masks a steel determination, say friends and acquaintances. And she has frequently defied expectations, first by opting as a teenager to convert to the Mormon faith, then forgoing a career and choosing a large family, against the wishes of her parents and at a time and place when many women of her generation were entering the workforce. She fought back from a devastating diagnosis of multiple sclerosis in the late 1990s to a point, now, where she seems the picture of health and has managed to keep the disease in remission.

“She has a very strong backbone,” says Margaret Wheelwright, a close friend of Romney who was a neighbor and fellow church member in Belmont, Mass., for about 20 years, before she moved to Hawaii with her husband, president of Brigham Young University’s Hawaii campus. “When she decides something, she goes for it all the way.”

Tuesday night, she will speak to the Republican National Convention in Tampa, Fla., tasked with showing that her husband is more than the cardboard cutout he can sometimes appear to be on the campaign trail. Blonde and attractive, she is a familiar presence at Mitt Romney’s side, but she can also be a bit of an enigma.

She’s gracious and maternal, happy to share recipes and talk about her children and grandchildren. But she can also come across as elitist and out of touch with the average American – even more than her husband – and her defenses flare up when she believes she or her family is under attack.

Unlike some political marriages, in which spouses offer teasing and even unflattering tidbits to reporters to humanize their home life (Michelle Obama did this so much she was criticized for “emasculating” her husband), the Romneys have famously claimed never to have fought.

Mr. Romney is adoring of Mrs. Romney and has said she helps anchor him. He was the first Massachusetts governor to request that his wife be included in his official portrait (in a picture on his desk). Mrs. Romney believes her husband can save America. And she accepts her own position as an irreplaceable muse.

"We are partners, true partners in every sense of the way," Mrs. Romney said in a CBS News interview recently. "I don't think he could do it without me. I don't believe he could. I couldn't obviously be here without him, either.”

Ann grew up in the same sheltered Michigan town that Mitt did, and attended the private Kingswood School – the sister school to Mitt’s Cranbrook School. Ann was 15 when she met Mitt (she is two years younger than he), and they soon fell in love.

Ann was the daughter of a self-made Welsh businessman (also the Bloomfield Hills, Mich., mayor) who had grown up in a coal-mining family and disdained organized religion. But at age 17, while Mitt was serving his 2-1/2 years of missionary service in France, she decided to convert to Mormonism, and then enrolled at Brigham Young University. Mitt's father, the governor of Michigan at the time, baptized her.

Ann has said repeatedly that her conversion had little to do with dating Mitt, and more to do with her own spiritual quest. Her two brothers later converted as well, as did her mother, shortly before her death in 1993.

“They don’t talk about it a lot, because it’s a very private thing for them, but when you’re with them you know they’re truly people of faith,” says Mrs. Wheelwright.

When Mitt returned from France, Ann was among those who met him at the airport. During the drive home, they got engaged.

Ann's decision to get married at 19 and to start a family right away (their first son, Tagg, was born on their first wedding anniversary) raised concern among her parents.

Her mother, who believed in zero population growth, was unhappy that Ann left school to move to the Boston area with Mitt, and that they were having so many children so quickly, and so young, says Ronald Scott, author of “Mitt Romney: An Inside Look at the Man and his Politics” and a distant cousin.

“Her mom in the 1970s is grumbling about the fact that [Ann] has converted to Mormonism and drunk the Kool-Aid, and it finally gets to the point where Ann says, ‘If you want to have a relationship with your grandchildren, cut it out,’ ” says Mr. Scott.

Not only did she stand up to her mother, he adds, but she also went on to finish her degree, taking night classes at Harvard’s Extension School. “This is a person who is her own person,” Scott says. “She didn’t need to finish her degree, but she did.”

Romney has said she often felt on the defensive about her decision to forgo a career and be a stay-at-home mother to five kids in Boston in the 1970s.

“My parents were questioning my choices, my peers were,” she told The New York Times this summer. “But … I was pretty resolute.”

This spring, the subject came up again, when Democratic strategist Hilary Rosen made the mistake of criticizing Mrs. Romney in a television interview, saying that she had “never worked a day in her life.”

The remark caused a brief firestorm, and Romney took to Twitter to defend herself.

"I made a choice to stay home and raise five boys. Believe me, it was hard work," she tweeted.

Ms. Rosen apologized, and the Obama campaign quickly distanced itself from her, denounced her remarks, and emphasized that Rosen wasn’t working with the campaign.

By all accounts, Romney was a devoted mother – and a busy one. Her five boys were born in the space of 11 years, and Romney raised them largely without help. (She also suffered a miscarriage, several months into the pregnancy, between the births of her fourth and fifth sons.)

“She is a fabulous mother and grandmother,” says Wheelwright, who also had five children about the age of the Romney boys, and used to spend time with Romney at the park as they watched their children play. “She always had a sense of humor, even when the house was being torn apart.… She’d laugh, and say, ‘That’s just boys.’ ”

She could be strict, too. Scott recalls an incident when her son Matt was 16, and the family was ready to drive to Cape Cod for the weekend. Matt was reportedly being obnoxious, and ragging on his mother, and finally she just got in the car and drove off to the Cape, leaving Matt alone for the weekend.

“It says two things,” says Scott. “She’s got a temper, and she’s not easy to push around. And also she raised her kids so that she could leave her 16-year-old son home alone for the weekend and know she’d come back and find the house in good condition.”

Wheelwright recalls being impressed that, even though the Romneys had money, they always had their sons – and Mr. Romney – out doing yardwork or pulling out stumps in the yard.

When their church would ask for volunteers to help students or families with a move, “We’d show up, and there would be Mitt and Ann and the five boys with their pickup truck,” Wheelwright recalls. “They really believed in service and in teaching it to their boys.”

Ann was briefly involved in civic life as well, running for and winning a seat on the Belmont town meeting representative in 1977 – long before her husband ever entered politics – though she served just a year.

“Mitt and Ann were very quietly gracious in the town of Belmont,” says Maryann Scali, who also served as a town meeting representative with Romney, though she says she knew her better from the League of Women Voters – where Ann twice offered up her home for fundraisers – and tennis, where Ann was competitive, but gracious.

In the presidential campaign, Mrs. Romney has had a more public persona, embracing her role as a mother and grandmother of 18, touting her faith in her husband’s ability to save the economy, and discussing her health battles with MS and breast cancer, and the role horseback riding has played in her recovery.

But she hasn’t always been an asset.

In Mr. Romney's first foray into public life – his failed 1994 Massachusetts Senate campaign against Ted Kennedy – Romney allowed herself to be profiled in a Boston Globe story that was disastrous.

She came across as naïve, privileged, and out of touch with average Americans – especially when she decried the financial hardship of early years with Mr. Romney, when they were both students living in a $62-a-month basement apartment with a cement floor and “we had no income except the stock we were chipping away at.”

She also told the reporter that the couple had never had a serious argument, as long as they’d known each other. Columnists at the time referred to her as a “Stepford wife.”

At the end of the campaign, after her husband had lost, Romney told another Globe reporter that “you couldn’t pay me to do this again.”

Still, by her own account, Romney was the member of the family most enthusiastic about her husband launching a second bid for the presidency this time around. She was also the one who encouraged him to step in to help the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympics – ensuring that he kept a high profile – back in 1999, even though it was soon after her diagnosis of multiple sclerosis.

She was diagnosed in 1998, after a year of health difficulties, and has spoken poignantly about the difficult period that followed.

“My life is finished. My life is over,” she recalled thinking when she got the diagnosis, speaking to a crowd in South Carolina last winter. She has referred to it as her “darkest hour.”

She also credited Mr. Romney, and his steadfastness and support, with bringing her back from the brink of despair. (It was a side of Mitt that was emphasized often last December, putting his reaction to his wife’s illness – and their long, happy marriage – in sharp contrast with the personal life of Newt Gingrich.)

She received treatments for a while, which she credits with helping to stop the progression of the disease. But it was horseback riding that she says ultimately saved her.

She had loved horses as a girl, and began riding again in Salt Lake City. Initially, she could barely get on a horse, but dressage – which involves far more intricate control of a horse through leg movements than most horseback riding – eventually helped her both physically and emotionally.

"Riding exhilarated me; it gave me a joy and a purpose," she told the Chronicle of the Horse magazine in 2008. "When I was so fatigued that I couldn't move, the excitement of going to the barn and getting my foot in the stirrup would make me crawl out of bed."

She shows no visible signs of her illness these days, though she has said she works hard to limit campaign appearances and get the rest and nutrition she needs. A brief flare-up around Super Tuesday was a wakeup call to be careful.

Her battle not to let MS – or the breast cancer that was diagnosed and successfully treated – get the better with her was, in many ways, a very Mormon reaction, says Scott.

“Originally, when [Romney] got MS people said that’s it for Mitt’s career because they’re so tight, he’ll stay home and take care of her and they’ll fade into oblivion. But they chose the opposite tack: Let’s conquer this and get on,” he says. “It’s a Mormon thing. You bury your burdens and smile and move forward.”

But if Romney has morphed into more of an asset to her husband’s political career than she was back in 1994, she still sometimes makes missteps – and can come across less as the warm presence her friends describe than a privileged woman who thinks her family is a step above everyone else.

There’s the business of dressage – which provides “dancing horse” images, stories about the $77,000 “business loss” claimed on the Romneys' 2010 tax returns due to her horses, and endless fodder for Stephen Colbert.

There are the occasionally off-key comments, as when she told ABC News in April that “it’s our turn now” for the presidency, or later, when she told ABC News, in response to queries about her husband’s refusal to release more tax returns, that “we’ve given all you people need to know” about their finances.

“She’s heading in the direction of being a liability to the campaign,” says one longtime acquaintance of the family, who asked that his name be withheld.

“She is as loyal as can be, and as nurturing as can be to her family, and values them more than life itself; it’s an endearing quality,” he adds. “But her weakness is the flip side of that: We’re at one level, then there’s the next level…. It comes across as demeaning to others.”

Scott, the Romney biographer, recounts a time when a Romney daughter-in-law had just moved to Boston with her new husband and was looking for work at the ad agency where Scott’s wife worked. Scott's wife was ready to offer her a job, when she got a call from the head of the agency, who had just heard from Mrs. Romney.

“Even though the kids were making this happen on their own, Ann wanted to make sure the deal got closed,” says Scott. Later, Mr. and Mrs. Romney also let it be known they thought their daughter-in-law’s salary was too low.

“There’s this almost guileless sense of entitlement and being willing to speak their minds that’s both annoying and refreshing at the same time,” says Scott.

As first lady of Massachusetts, Romney kept a low profile, giving few public appearances. Near the end of his tenure, Mitt Romney gave his wife a position as an unpaid liaison for federal faith-based initiatives.

But her rising role in the 2012 campaign seems to indicate a willingness to be somewhat more prominent, should her husband win.

In interviews, Romney has expressed admiration for first ladies such as Barbara Bush, Nancy Reagan, and Mamie Eisenhower, and said she could envision using her role to be an advocate for children and those who suffer from MS.

“I would think she’d be somewhat of a cross between a Michelle Obama and a Laura Bush,” says Scott. “I actually think she will be an activist in some areas,… once the dust settles.”