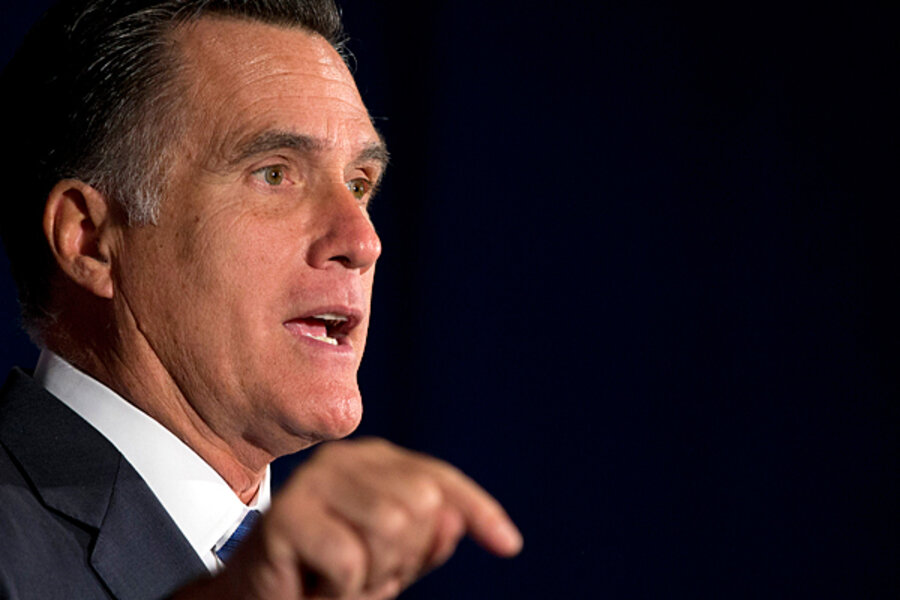

Can Mitt Romney damage Obama over Benghazi attack?

Loading...

| Washington

Suddenly, Mitt Romney and the Republicans are attacking President Obama on an election issue on which the incumbent looked to be almost untouchable – foreign policy. Can it work?

The events of Sept. 11 in Benghazi, Libya – the firebombing of the US consulate that resulted in the deaths of four American diplomats including the ambassador to Libya, Christopher Stevens – have provided an opening to question Mr. Obama’s handling of an international crisis, and in particular, of American security overseas, foreign policy experts say.

Yet Republicans face their own pitfalls in zeroing in on the previously barren soil of foreign policy.

One is that many independent voters, in particular, have an aversion to the kind of muscular rhetoric about how the US should act in the world that Mr. Romney and a number of his surrogates have used in their broadsides at Obama, says Aaron David Miller, a foreign policy specialist with long experience in both Republican and Democratic administrations.

“There are vulnerabilities [for Obama], for sure, that flow from the latest series of events. The questions that are resonating are about competency and whether there was too much nonchalance … about the security of our diplomats and our diplomatic missions,” says Mr. Miller, now a Middle East expert at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington.

Calling this new vulnerability on foreign policy “a clear shift in focus” on an issue where Obama seemed previously almost unassailable, Miller says, “Does it limit the president? Yes. But can it cost him the election? No.”

Until the Benghazi attack, Obama was considered to have greatly improved Democrats' standing with the public on issues of national security. He pledged to get Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden and he did, he ordered many more drone attacks on militants in Pakistan than President George W. Bush did, and perhaps most important, a number of potentially devastating attacks on the US were foiled.

When asked at a press conference last December about Republican attacks on his firmness with America’s adversaries, Obama answered, “Ask Osama bin Laden and the 22-out-of-30 top Al Qaeda leaders who’ve been taken off the field whether I engage in appeasement.”

But Benghazi casts doubts on the president’s preparedness for the uncertainties resulting from upheaval in the Middle East, says Miller. Moreover, he adds, the administration has a “messaging problem” in that there was a “clear effort at painting these events … in a way to make the administration’s response look more favorable.”

But to compare the Benghazi attack to the Iran hostage crisis and the 1980 election is an exaggeration, Miller says. As for former Gov. Mike Huckabee (R) characterizing the administration’s changing account of Benghazi – from a spontaneous mob flare-up to a terrorist attack – as “Obama’s Watergate,” Miller says, “Oh, please.”

A new Washington Post poll shows Romney leading now among independents on whom they most trust on the broad issue of “international affairs.” (The poll suggests that the same independents still prefer Obama on handling terrorism and an international crisis.)

That suggests Romney can capitalize on the issue of Obama’s “competence” as raised by the Benghazi attack – but not, Miller says, if the Republican challenger continues to go from there to attacking Obama as weak on Iran or saying he “lacks resolve” in the Middle East in a way that suggests Romney would steer the US into another war.

“Only two issues move voters in the area of foreign policy, and those are one, security, and two, prosperity,” Miller says. To the extent that a war with Iran could trigger skyrocketing gasoline prices, he says, and as long as there are no terrorist attacks on American soil, “it’s going to be hard for Romney to move the dial with his talk of a tougher approach” to the world.