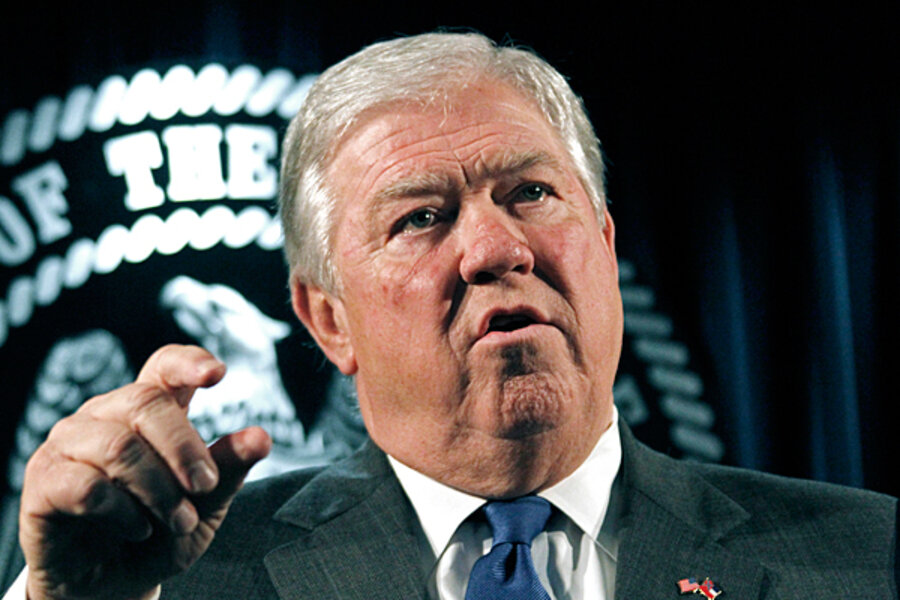

As debate roars over Haley Barbour pardons, five released convicts vanish

Loading...

| Atlanta

Five prisoners pardoned and released Sunday by outgoing Mississippi Gov. Haley Barbour (R) have gone missing amid a burgeoning debate about whether the 200-plus individuals given clemency by the governor merited mercy under the state constitution.

Mr. Barbour's decision to pardon a record number of convicted Mississippians – a controversial final act of his term-limited governorship – has sparked shock, anger, and even fear. Family members of at least one victim say they're worried about their safety.

The mass pardon has set off a national debate about whether Barbour exceeded his executive authority or whether the pardons were an appropriate remedy to an unjust legal system.

On Wednesday, circuit judge Tomie Green, after a complaint by state Attorney General Jim Hood, blocked the release of 21 of the convicts because they may not have met a public notice requirement under the state constitution. Judge Green also mandated that the five men released over the weekend report back to the state and attend a Jan. 23 hearing, but Mr. Hood said Thursday that the men can't be found.

"These convicts got out and hit the road," Hood said, according to CNN. “This is probably going to end up in some attempt by us to have fugitive warrants issued for these people. There’s going to be a national search for some of them.”

The five pardoned prisoners, according to the Associated Press, are four convicted murderers – David Gatlin, Charles Hooker, Anthony McCray, and Joseph Ozment – and one convicted robber, Nathan Kern, who was serving a life sentence. All of them had worked as inmate trusties at the Governor's Mansion.

Barbour's actions, says University of Notre Dame law professor Jimmy Gurulé, a former federal prosecutor, exceeded accepted norms of executive power, especially by giving freedom to convicted murderers without properly notifying the victims' families.

“The symbolism of this, the message that it sends to families, is so insensitive and so insulting to the memory of these murder victims. It's mind-boggling,” says Professor Gurulé.

Others say that Barbour's pardons highlight the necessity of clemency as an executive power. Some point to Alexander Hamilton's position in The Federalist Papers where he noted that “without an easy access to exceptions in favor of unfortunate guilt, justice would wear a countenance too ... cruel.”

“I'm sure the governor has seen, as the rest of us have, the increasingly unjust nature of our court system these days,” writes Mary Kate Cary, a former Barbour speechwriter, in a U.S. News & World Report op-ed. “Is there anyone who thinks our criminal justice system isn't tough enough? Haley Barbour is a smart, humane man. He understands the need for mercy and compassion in our criminal justice system. He's done nothing wrong.”

Much of the anger stems from the fact that the public wasn't privy to Barbour's private deliberations and fact-finding in each case. “It's very difficult to answer if Barbour went too far without more complete knowledge of these individual cases,” says John Winkle, a political science professor at Ole Miss in Oxford.

“Approximately 90 percent of these individuals were no longer in custody, and a majority of them had been out for years,” Barbour explained in a statement. “The pardons were intended to allow them to find gainful employment or acquire professional licenses as well as hunt and vote. My decision about clemency was based upon the recommendation of the Parole Board in more than 90 percent of the cases.”

Meanwhile, incoming Gov. Phil Bryant (R) has asked lawmakers to study whether a constitutional amendment may be necessary to limit the executive branch's pardon powers in the state. “The governor believes a constitutional amendment is the right way to address such an important issue,” Mick Bullock, Governor Bryant's spokesman, said in a statement.

Green has set a Jan. 23 hearing to determine whether Barbour's pardons were, in fact, legal. Twenty-one of those pardoned remain in custody as the state searches for the five missing ex-convicts, who, under the conditions of a Mississippi pardon, are technically no longer required to check in with the state. Unless Green makes a different finding, their criminal records are clean.