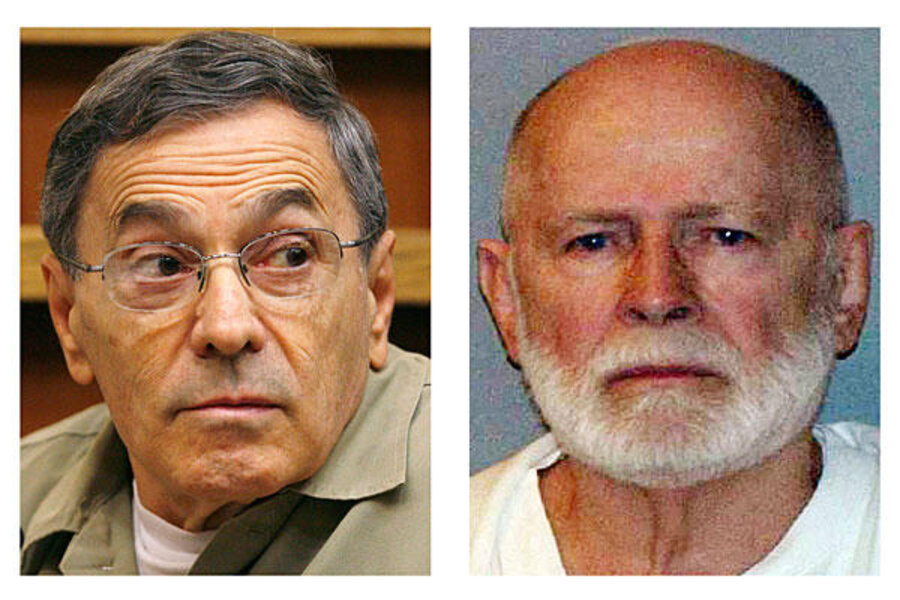

Whitey Bulger trial: Are underworld figures reliable witnesses?

Loading...

| Boston

In the trial of James “Whitey” Bulger, the former crime boss’s business partner is enduring multiple days in the witness chair for a simple reason: The prosecution views him as a source of vital evidence, and the defense wants to show that his information isn’t trustworthy.

So the days keep ticking by as Stephen “The Rifleman” Flemmi testifies.

We’ve learned that he doesn’t care for his nickname, which he got for exploits during military service in Korea.

We’ve learned that he has a sense of humor, but is also a self-described “aggressive” personality.

And now, after hearing his version of events in several alleged murders by Whitey Bulger, we’re learning more about the background behind his willingness to become a cooperating witness for the US government.

On Wednesday, defense attorney Hank Brennan got Mr. Flemmi to recount the difficult prison conditions he encountered back in 1999, and to say that those conditions “figured into my decision to cooperate.”

Whether admissions such as that damage Flemmi’s credibility in the eyes of jurors remains to be seen. But a central feature of this organized-crime trial, which has been running for some six weeks, is that it pits various less-than-reputable characters against one another.

The prosecution is leaning on various confessed criminals to go after another alleged malefactor. Although Bulger is pleading “not guilty” to 19 murders and other racketeering-related charges in the federal case against him, his attorneys have acknowledged that he was a professional criminal involved in illegal activities such as gambling and loansharking.

Defense lawyers are trying to cast doubt on the prosecution’s case by suggesting that the cooperating witnesses have benefited by being willing to say things – including lies – that help the government to build a case.

Bulger himself is a potential witness when the defense lays out its case, although he may end up waiving his right to testify. He spent 16 years on the run as one of the FBI’s “Most Wanted” before being caught in 2011.

His former crime partner, Flemmi, was questioned Wednesday about the conditions of a state prison in Walpole, Mass., where he was held.

He said the food was bad (“I lost 35 pounds”), there was nothing much to do (no TV, radio, and “they didn't provide any books either”), and he spent most of each day locked up without contact with other people.

When he did see other inmates, they often hurled insults at him, Flemmi acknowledged under questioning by Mr. Brennan.

And “the phone was always broken,” Flemmi said, so it was hard to contact his attorney or family members.

By Flemmi’s account, the desire to escape those conditions affected his interest in becoming a cooperating witness, but didn’t prompt him to lie.

Brennan tried to chip away at that proposition, citing numerous instances in which Flemmi has given differing accounts of certain events in legal proceedings over the past decade.

The goal is to raise “reasonable doubt” about Bulger’s guilt in jurors’ minds.

A challenge for the defense, of course, is that casting doubt on Flemmi’s credibility isn’t the same as causing jurors to toss aside his word entirely. (Flemmi avoided the death penalty, and is serving a life sentence.)

Moreover, some key evidence at the trial comes from sources that are things rather than people: the illicit guns and some $800,000 in cash found in the California apartment where Bulger was apprehended.

After the court’s regular session concluded on Wednesday, Judge Denise Casper heard from the attorneys on both sides regarding the next stage of the trial.

One conclusion that emerged from the back-and-forth: The defense-side witness list is arranged to keep boring in on the same theme: calling into question the reliability of prosecution testimony, as opposed to emphasizing evidence designed to prove Bulger’s innocence.

Prosecutors with the US Department of Justice hope to have Judge Casper exclude some of the defense witnesses, on the grounds that their testimony is merely peripheral. It relates to the witnesses but not directly about Bulger’s case, the attorneys argue.

Assistant US Attorney Brian Kelly also complained about the Bulger team’s efforts to combat the idea that their client was an informant, despite a voluminous FBI file to the contrary.

Bulger’s lawyers want to call witnesses to show that corrupt FBI agents sometimes lifted words from reports on other informants, and put it in Bulger’s file.

Prosecutors say this, too, is peripheral to the case.

“Being an informant is not a crime,” Kelly told the judge. He asserted that the defense attorneys are trying to waste time and confuse the jury.