Whitey Bulger prosecution sums up case against one of Boston's 'most vicious'

Loading...

| Boston

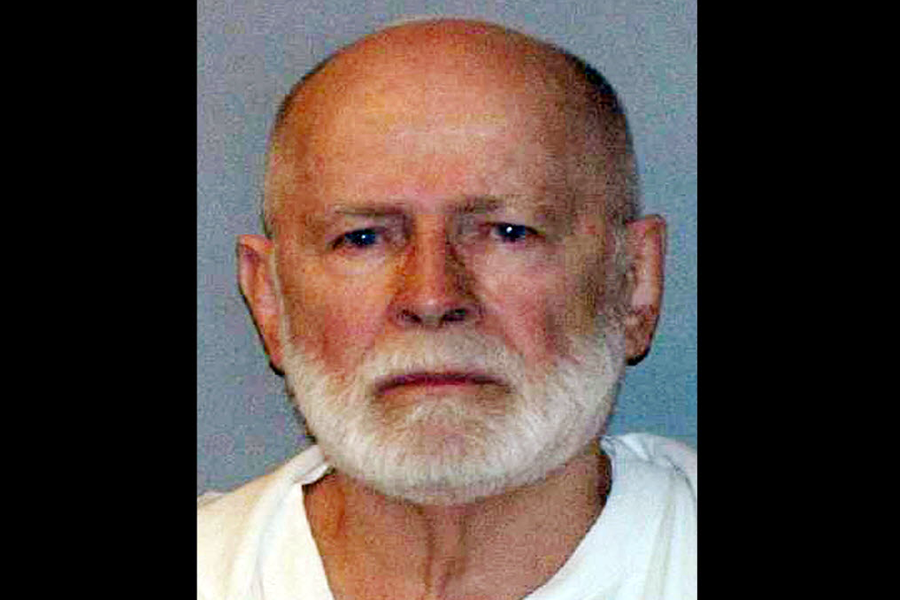

For nearly two decades, the face of alleged Boston mobster James “Whitey” Bulger was splashed across billboards and posters across the country, a larger-than-life character second only to Osama bin Laden on the FBI’s Most Wanted List.

But the 83-year-old looked much smaller on Monday as he sat hunched beside his lawyers in Boston’s federal courthouse, scribbling furiously into a notebook as the prosecuting attorney laid out in gruesome detail the specifics of Mr. Bulger’s alleged crimes – including his participation in 19 murders – in the closing argument of his murder and racketeering trial.

Almost 19 years after Bulger was first indicted and fled Boston – two years after he was finally captured in California and eight weeks after his long-awaited trial convened – Assistant US Attorney Fred Wyshak summed up the government’s sprawling case against the long-feared figure.

He was “one of the most vicious, violent, and calculating criminals ever to walk the streets of Boston,” Mr. Wyshak told the members of the jury, who have spent the past two months listening to the testimony of more than 70 witnesses, including Bulger’s alleged former criminal partners, bookies, drug dealers, former FBI agents, and families of the victims.

One by one, Wyshak wound through the 32 counts of the indictment against Bulger, which span the alleged gangster’s reign as the head of Boston’s Winter Hill gang in the 1970s and '80s, and include charges of murder, money laundering, extortion, and gun hoarding.

But even as Wyshak outlined the voluminous evidence against Bulger, he spent much of his three-hour closing argument cautioning jurors to ignore what he called a raft of “irrelevant issues” and evidence that the defense has attempted to draw into the case.

In particular, at issue throughout the long trial has been Bulger’s status as an informant for the Boston office of the FBI – an allegation he has repeatedly denied.

“In the final analysis, ladies and gentlemen, you don’t have to decide whether Mr. Bulger was an informant or not,” Wyshak said. “That’s not something that’s an element of any of these crimes. So why has it been so hotly contested in this trial? Because Mr. Bulger cares more about his reputation as an FBI informant than he does about his reputation as a murderous thug.”

Putting it even more succinctly at another point, he told jurors, “whether he’s an informant or not, he’s a murderer.”

Much of the evidence the government brought against Bulger throughout the trial came in the form of testimony by former criminal gang members, several of whom brokered deals in their own cases in return for testifying against their former boss.

During his closing argument Wyshak urged the jurors not to allow the questionable character of those mobsters affect how they interpreted the testimonies.

“It’s not whether you like the witness,” he said. “Nobody likes these men.”

Instead, he said, the jury was obligated simply to consider the facts – many of them brutal and damning. During the trial, several of Bulger’s closest former associates, including his business partner, Stephen “The Rifleman” Flemmi, hit man John Martorano, and one-time Bulger protégé Kevin Weeks, repeatedly testified to either witnessing or directly participating in execution-style murders directed by Bulger – hits against rivals, bystanders, and others who threatened the gang’s ability to run their South Boston criminal world.

Over the course of the trial, the prosecution called 63 witnesses, and the defense 10 (Mr. Martorano was called by both sides). But Bulger himself was not among them. The defendant announced Friday that he would not testify in his own defense, claiming a now-deceased federal prosecutor had previously promised him immunity and that his entire trial had been a farce.

“As far as I’m concerned, I didn’t get a fair trial and this is a sham,” he spat at the judge. “Do what yous want with me. That’s it. That’s my final word.”

“You’re a coward!” a woman yelled back from the spectator gallery. It was Patricia Donahue, whose late husband is among Bulger’s alleged victims.

On Monday, Bulger once again sat quietly at the defense table, listening to Wyshak’s hurried version of the epic story that had made him one of America’s most watched gangsters.

At one point, the prosecutor described the day in 1981 when Bulger lured a young woman named Debbie Davis, then Mr. Flemmi’s girlfriend, to a South Boston house. There, he said, Flemmi and Bulger strangled Ms. Davis to death, stripped her body and pulled out her teeth with a pair of pliers, then buried her under the house.

It was “a horrific murder,” Wyshak said simply.

Bulger didn’t even look up.