Whitey Bulger verdict: Mob boss is convicted of 11 killings, racketeering

Loading...

| Boston

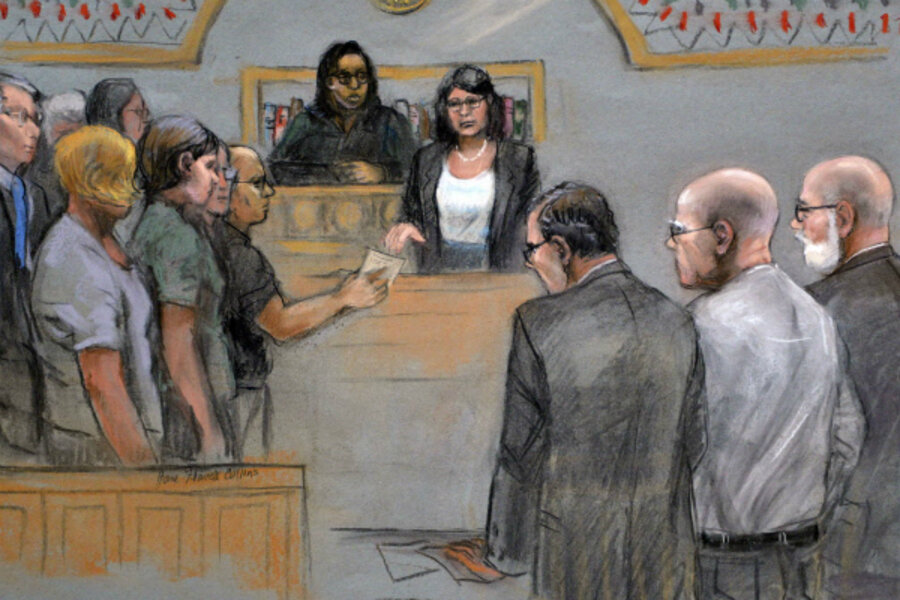

With family members of murder victims holding hands and looking on, a federal jury in Boston on Monday found James "Whitey" Bulger guilty of conspiracy and racketeering charges that will likely put him behind bars for the rest of his life.

Mr. Bulger had been charged with 32 counts of racketeering, including 19 murders, with the main racketeering charge encompassing 33 individual criminal acts and all of the killings. The jury found him guilty of 31 racketeering charges including the killings of 11 people.

In many ways, it seemed a sober, somber end to a once-flamboyant criminal career that encompassed decades of mayhem in his South Boston neighborhood, including murder, money laundering, extortion, and drug trafficking by Bulger’s Boston Winter Hill gang from the 1970s into the '80s.

After he was finally indicted in 1994, Bulger went on the run, eluding authorities for 16 more years – his face appearing on billboards and wanted posters across the country. He found a steady spot on the FBI’s Most Wanted List and even became the subject of Hollywood movies and multiple biographies, until finally Bulger and his companion, Catherine Greig, were arrested in Santa Monica on June 22, 2011.

In the end, though, the 83-year-old Bulger did not take the witness stand to defend himself. Nor did his defense team do much to rebut the idea that he was a drug dealer, loan shark, and extortionist, focusing instead on refuting the prosecution's claim that Bulger had been an FBI informant.

It is a claim that Bulger, himself, has long denied. He didn't want to be seen as an informant, or "rat." Bulger also had claimed that a part of his personal criminal code was that he did not murder women. But the jury found that he played a role in the murder of Deborah Hussey, as well as 10 other victims who were men.

During the seven-week trial, the jury heard a parade of former FBI agents and convicted murderers who testified Bulger was, in fact, an FBI informant – and that this was perhaps the chief reason that he and his gang were able to conduct their reign of crime and terror for so long.

Former FBI agents, as well as Bulger’s former gang confederates, testified to the FBI’s role in protecting Bulger from potential indictments so that he could continue feeding the bureau information about the Italian Mafia operations in Boston. For the FBI, they testified, the single-minded pursuit of La Cosa Nostra in Boston trumped the criminality of Bulger and his fellow criminals.

Among those testifying that Bulger was a top FBI informant were three former Bulger gang associates who confessed to committing murders at his side, including Stephen “The Rifleman” Flemmi, Kevin Weeks, and John Martorano.

Their testimony was instrumental, in part, because of the loss of credibility of the FBI over the years. During the Bulger trial, the government’s own witnesses testified to extensive government corruption by FBI agents in the Boston office, with Bulger and his gang bribing their handlers with tens of thousands of dollars, lavish gifts, and vacations.

Indeed, perhaps the single most significant impact of the Bulger case may be its effect on the FBI itself – and how it chooses to manage its extensive network of criminal informants in the future – so as to avoid having those informants turn the tables and corrupt the crime fighters themselves, several analysts say.

“It’s alarming, the extent of FBI involvement in Bulger’s crimes that this trial has revealed,” says Michael Coyne, associate dean at the Massachusetts School of Law in Andover, Mass., who has followed the trial closely.

In the end, FBI corruption made the prosecution of Bulger more difficult, especially when the jury had to listen to government’s own witnesses talk about FBI agents assisting with the murder of a witness, “or listen to former FBI agents complicit with Mr. Bulger’s criminal enterprise,” Mr. Coyne says.

After that decades-long dance between the violent Bulger gang and the FBI agents who knew about it was revealed in 1998, lawmakers were aghast. Even while Bulger was accused of participating in 19 murders, his own FBI handler was convicted in 2002 of racketeering and, in 2008, of second-degree murder for leaking information to Bulger that led to a murder.

The Bulger-FBI linkup proved to be a bombshell for the bureau. It adopted tough new guidelines for informants in light of the revelations, and congressional investigations followed.

"What happened in New England over a forty year period is, without doubt, one of the greatest failures in federal law enforcement history," the House Committee on Government Reform conceded in a 2004 report: "Everything Secret Degenerates: The FBI's Use of Murderers as Informants."

Under the new FBI guidelines, confidential informants now undergo scrutiny for suitability before being approved and are regularly warned about limits on their authority. Informants may engage in otherwise illegal activities only as they are justified according to unusual circumstances and only after those activities are "carefully defined" and approved by Department of Justice and FBI personnel, the DOJ reported in 2005.

But the trial has brought all of the old failures to the surface to be seen once again – with hopes that it will be a reminder of the dangers and make the process of using criminal informants less poisonous for law enforcement.

“It has certainly shed light on the extent of the problem – and hopefully awakened the FBI and other government officials to look at their internal policies,” Coyne says, “precisely so this type of abuse and involvement with criminal enterprises doesn’t go on in the future.”

With this verdict, the jury has found that Bulger played a role in the murders of Deborah Hussey, Paul McGonagle, Edward Connors, Thomas King, Richard Castucci, Roger Wheeler, Brian Halloran, Michael Donahue, John Callahan, Arthur Barrett, and John McIntyre.

US District Court Judge Denise Casper scheduled sentencing for Nov. 13. Bulger faces a maximum of life, plus 30 years, in prison.