50 years ago, Muhammad Ali 'shook up the world' in Miami Beach

Loading...

| Miami Beach, Florida

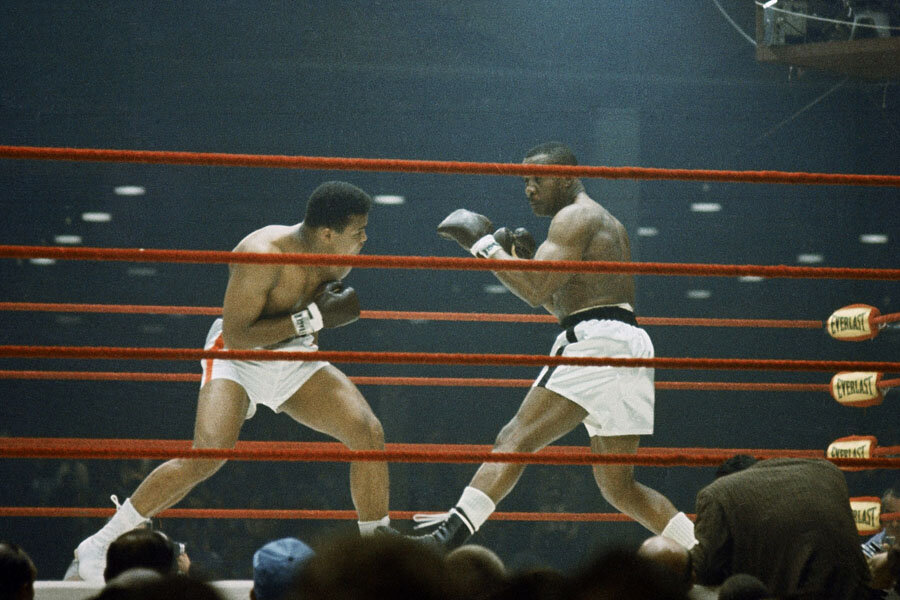

Fifty years ago, an upstart American boxer who later became known as Muhammad Ali "shook up the world" when he dethroned Sonny Liston to claim the heavyweight championship of the world in Miami Beach.

That victory on Feb. 25, 1964 was the last time Cassius Clay fought under his real name, announcing after that he was joining the religious black power movement, the Nation of Islam, and changing his name to Muhammad Ali.

The six-round bout that ended when Liston threw in the towel, launched Ali to international fame, giving him the stage to successfully protest everything from racial segregation to the Vietnam War, while declaring himself to be "The Greatest."

To mark the 50th anniversary of the fight the downtown HistoryMiami museum is celebrating the event with a month-long art and photo exhibition opening this week, including several previously unpublished images.

Today, a plaque commemorates the bout at the entrance to the Miami Beach Convention Center where the fight was held. A brass medallion embedded into the concrete exhibition floor marking where the ring once stood, has since disappeared.

Miami Beach in the early 1960s was seeking to launch itself as a tourist destination. The week before the Clay-Liston fight the city had hosted the Beatles for their second appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show, broadcast live from the beachfront Deauville hotel.

Miami Beach was also a hub for boxing, centered on the Fifth Street Gym, a ramshackle place only a few steps away from the beach. The old gym was knocked down in 1993. In its place stands a shopping mall.

But in the early 1960s, the hotels and beaches were still segregated, while across the bay on the mainland the civil rights movement was bubbling and Miami's black Overtown district was home to a vibrant live music club scene that attracted the greatest jazz musicians of the era.

"There were lunch counter sit-ins at Woolworth's and Burdines in Miami a decade before the more famous one in Greensboro," said Alan Tomlinson, producer of the PBS documentary "Muhammad Ali: Made in Miami," referring to the North Carolina civil rights protests in the 1960s.

"The Black Muslims were very, very active down here, and Cassius Clay got involved with them. He liked their message," Tomlinson said.

Clay won the gold medal at the Rome Olympics in 1960 but was still fuming at his lack of acceptance by whites.

Clay would make Miami his base, putting his career in the hands of Chris and Angelo Dundee, who promoted fights and trained boxers at the Fifth Street Gym and were Miami's boxing ringleaders.

It was Angelo, who already trained a handful of championship boxers, who saw that Clay could be trained into a champion.

Dundee, who died in early 2012, was more than a trainer who knew how to mold a winning fighter. He also helped channel Clay's brash personality.

"Archie had him sweeping the gym and working like a dog. Angelo felt he was like a thoroughbred race horse," Tomlinson said.

"If Angelo wanted Clay to work on his jab ... he would not say, 'Muhammad I want you to work on your jab' because then he'd never do it," said Ramiro Ortiz, a boxing historian and former banker who hung around the Fifth Street Gym as a kid.

"Angelo would say 'Muhammad that jab's looking better than it's ever looked before!' and all (Ali) he would do is jab," he added.

"FLOAT LIKE A BUTTERFLY..."

Most observers at the time argued Clay's style and lack of experience would doom him to lose to the fearsome Liston, who had barreled through several prior contenders and learned to box during two prison sentences.

"There was sheer terror Liston was going to kill us," said Ferdie Pacheco, Clay's ringside doctor and the sole surviving member of the boxer's ringside team. "Clay was taunting him and you don't make a giant like that mad."

Clay eschewed traditional boxing techniques. He leaned back to dodge punches, which left him off balance and susceptible to a knockout punch. He also bounced and skipped around the ring, later coining the phrase, "Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee. His hands can't hit what his eyes can't see."

At the same time the Dundees were also working furiously to keep quiet Clay's alliance with Malcolm X and the Black Muslims, which if made public threatened to cancel the fight.

After the fight a jubilant Clay declared, "I'm the greatest thing that ever lived ... I shook up the world."

Without that fight Cassius Clay may have never become Muhammad Ali and the legend may have never evolved, says Pacheco.

"It made him a celebrity," Pacheco said. "It made him great, and everything that he did always seemed to work out."