Can a city be too liberal for Californians? San Francisco tests limits.

Loading...

| SAN FRANCISCO

San Franciscans pride themselves on being tolerant and compassionate, a city of second chances.

But many in this progressive stronghold are dismayed at the state of their beloved city, which like other urban centers has seen a pandemic spike in homelessness, drug use, and homicides, not to mention student learning loss – with subsequent political reaction.

Why We Wrote This

San Francisco has long been a way-shower for progressive ideals. But progressive policies haven’t kept up with crisis-level social welfare needs – causing political backlash that may signal a deeper shift in liberals’ commitment to compassion-driven governance.

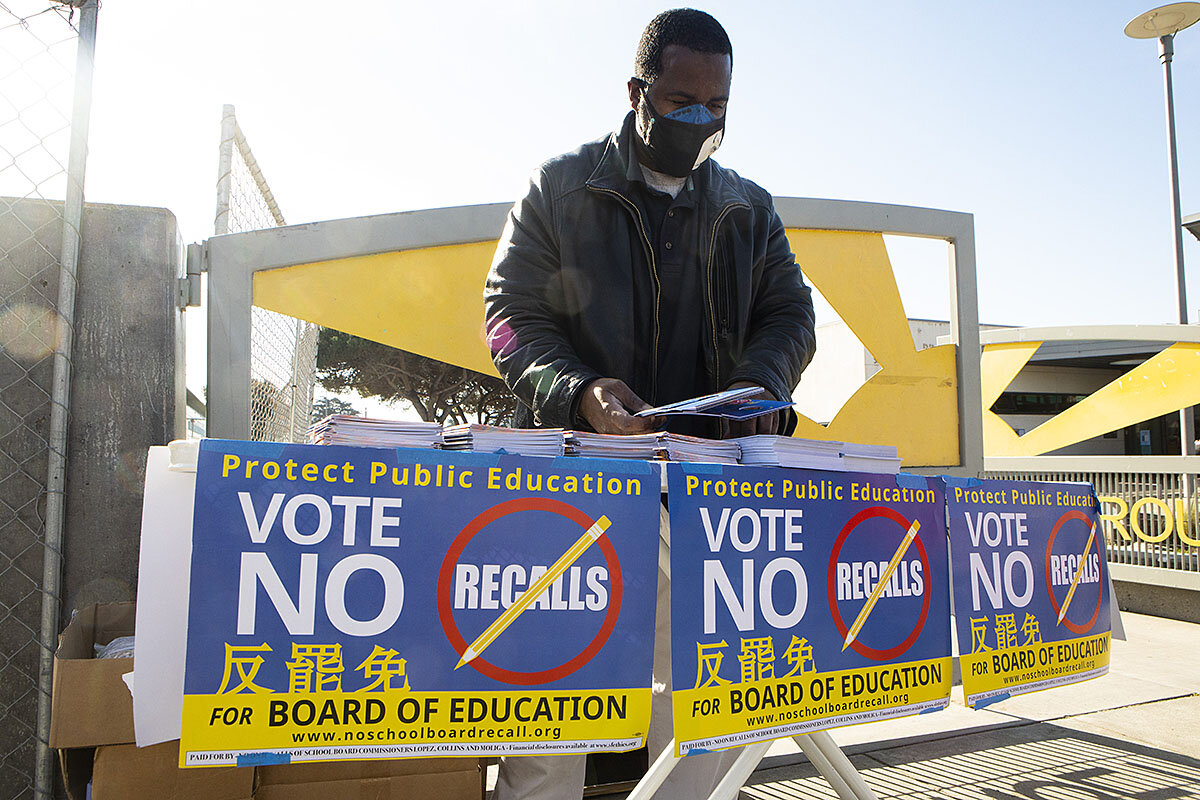

Tuesday, angry voters overwhelmingly recalled three members of San Francisco’s school board, which made national headlines for its focus on renaming 44 schools during a historic pandemic shutdown. The city’s District Attorney Chesa Boudin faces a recall election in June, fueled by criminal justice reforms that opponents say coddle criminals.

In the Tenderloin neighborhood, where all these crises have come to a head, Democratic Mayor London Breed has enacted a state of emergency – a move she called “tough love.” Despite improvements, crime, drug use, and homelessness are still on full display, giving pause to some deep-blue Democrats.

But not Del Seymour. He’s lived in the Tenderloin for more than 30 years and guffaws at the premise that San Francisco is a liberal city. “That is the biggest San Francisco myth of anything,” he exclaims. “These people are so holier-than-thou,” he says of the NIMBY crowd. “It went from Summer of Love to not in my backyard.”

Before the pandemic, before San Francisco closed its public schools for a year or more, Beth Kelly was on a political “cusp” between identifying herself as a progressive Democrat and a moderate one. Not anymore. This environmental lawyer and mother of two young children says she’s now “solidly in the moderate camp.”

That move may not sound like much of a change to people outside the Golden State. But it’s a significant shift in this famously liberal city where voters are pushing back against progressive policies that they see as ineffective.

On Tuesday, Ms. Kelly and other angry voters overwhelmingly recalled three members of the San Francisco school board. During a historical pandemic shutdown, the board made national headlines for its focus on renaming 44 schools, including those named after Abraham Lincoln and George Washington, while elementary schools were closed for 12 months and high schools for 17. In June, the city faces another test in a special election to boot District Attorney Chesa Boudin, one of a new cadre of progressive prosecutors across America. In December, the city’s mayor, London Breed, declared a state of emergency in the downtown Tenderloin district, vowing to end “the reign of criminals who are destroying our city.”

Why We Wrote This

San Francisco has long been a way-shower for progressive ideals. But progressive policies haven’t kept up with crisis-level social welfare needs – causing political backlash that may signal a deeper shift in liberals’ commitment to compassion-driven governance.

Could it be that San Francisco, where Republicans are only 6.7% of registered voters, has found the limits of liberal idealism?

From her home in San Francisco’s Inner Sunset District, Ms. Kelly describes “a shift rightward,” or at least “still left, but maybe less left” than before the pandemic. “People are getting fed up with ineffective policies, and homelessness and drugs.”

Others put it slightly differently. “This is a revolution for governance,” says Siva Raj, one of the parent organizers of the school board recall. It’s not right vs. left, he explains, but a grassroots demand “for elected leaders to actually govern.”

Left or right, up or down, many San Franciscans are dismayed at the state of their beloved city, which like other urban centers in the country has seen a pandemic spike in homelessness, drug use, and homicides, not to mention student learning loss – with subsequent political reaction. In New York, concern over public safety propelled a former police officer – Democrat Eric Adams – to the mayor’s office. In Boston, Mayor Michelle Wu, a Democrat, cleared a ballooning homeless encampment with a combination of social workers and bulldozers. Meanwhile, Glenn Youngkin last year recaptured the Virginia governorship for Republicans, running on a message of more parental control over education. In Congress, Senate Republicans are again swinging at their favorite liberal punching bag, messaging on the San Francisco mayor’s “reign of criminals” comment from December. If even San Francisco Democrats are unhappy, well then.

“Republicans are going to cash in on popular revulsion on what appears to be an increasing criminality, certainly murders, as well as homelessness,” says Jerry Roberts, former managing editor of the San Francisco Chronicle and biographer of former San Francisco mayor and now Sen. Dianne Feinstein, who was the last person to face a recall on the city ballot. That was in 1983.

The latest surge in socioeconomic crises brings liberalism to yet another threshold. Does this represent a pivot point for the city – or even Democrats nationwide, who might be ready to temper some of their most progressive instincts on COVID-19, crime, and education just as a crucial midterm election looms? Or, as Mr. Raj suggests, is it a call for politicians to refrain from “symbols over substance” and do the hard work when it comes to budgets, crime, and schools?

As Ed Ho, a public school parent who voted for the recall, puts it: “We actually support criminal justice reform. We actually support Black Lives Matter. We want a better society. We want to close the achievement gaps in education. But the way that it’s being pursued now in this city is just off the rails.”

Out with the school board

On a recent Thursday at 7:15 a.m., Ms. Kelly opened the door to her world – a “work-from-home hustle” of juggling clients and children. Inside, it’s hardly the “chaos morning” she described when setting up this appointment. Her husband, a civil engineer, is asleep upstairs, having worked the night shift. He left word not to use his name or the names of the kids.

Things quickly and quietly settle down, with mother and 5-year-old daughter on the sofa, reading aloud. Her 7-year-old son free-ranges with toys and books in the remodeled kitchen-dining room where a wall of large windows opens to a terraced garden. Eventually mom and kids migrate onto the living room rug, where they play a favorite math game with cards. Both kids are really good at this. Grandma arrives to pick them up, with the boy heading to second grade at a public school, and the girl to preschool.

Parents of school-age children know how tough these last couple of years have been. As this attorney mom explains, her son has a “glitter sprinkle” of learning needs, and suffered educational setbacks without his individualized support from in-person school. Now that school is open, things are so much better. But last summer, Ms. Kelly was hospitalized for a month because “it was just too much – the pressure on families, working families.”

Added strain came from her devotion to Zooming in on hourslong school board meetings that ran late into the night. One issue that caused an uproar was a rushed process to eliminate the entrance exam at prestigious Lowell High School in order to fight racism at the school and provide more opportunities for Black and Latino students. Parents of Asian students, who made up slightly more than half of the student body, were particularly upset. A judge ruled the board’s decision-making process violated the law, and declared its decision null and void.

Ms. Kelly’s interests, however, were focused on budget challenges. “I started looking at some of the board meetings. No one was paying attention to the structural deficit.” An admitted numbers geek, she began tweeting out reports from every meeting, missing family dinners, missing swim lessons. Under the hashtag #BethBreaksItDown, she became a tweeting sensation. The outgoing board inherited the nine-figure deficit, but she says the board’s inaction meant that more than $100 million in federal funds intended to catch kids up from learning loss instead went to fill the budget hole.

“I found the whole process extremely disturbing. ... It’s a crisis. It’s nuts and bolts. You have to balance your budget.” Also disturbing – the nasty social media backlash from progressives who derided this white mom for sending her kid to a “white” school that is just 35% white. Another target for derision: the success of her school’s PTA in fundraising.

“This year has made me feel very unwelcome in both the public-schools sphere and certainly in the more progressive wing of things,” Ms. Kelly states. “There is a real liberal discomfort with affluence and whiteness.” That’s a lot of internal conflict for a city where two-thirds of the population is registered Democrat, half the population is ethnically white, and the median household income is nearly twice the national average.

Nearly 30% of San Francisco’s K-12 students go to private schools. If progressives keep shunning these families, she explains, enrollment in public schools will continue to decline, and so will funds, which are based on enrollment. That means closing schools. “We need to bring those families back in,” she says. “We need education for everybody.”

Clash in the city of tolerance

San Franciscans pride themselves on being tolerant and compassionate, a city of second chances. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, a California Democrat, likes to invoke the prayer of her city’s patron saint, St. Francis: “Lord, make me a channel of thy peace.”

This tolerance and activism, for instance, brought a sea change in the nation’s LGBTQ culture and laws. In his history of California, the late Kevin Starr writes that as a port city, with a “live-and-let-live” attitude, San Francisco attracted gays and lesbians from the 19th century onward.

Easton Agnew-Brackett, also a Democrat and resident of the Sunset District who voted for the school board recall, loves San Francisco for its weather, architecture, and stunning beauty – all of which make this the most expensive place to buy a house in the United States (median sales price: over $1.3 million). This college counselor grimaces over the “very, very expensive” cost of living, but embraces the city’s values. “As a gay parent, I am treated just like any other parent. And I can walk down the street with my kids and my husband and people don’t give me weird looks.”

But that tolerance seems to elude city politics: “Like a knife fight in a phone booth,” the saying here goes – with consequences that can be fatal. In 1978, a former San Francisco supervisor assassinated Mayor George Moscone and Harvey Milk, the first openly gay man elected to political office in the nation.

Ms. Kelly says equity, compassion, and social justice are her “core beliefs,” and she and others are deeply troubled by the demonization of those who disagree with progressives on the school board issue. Anti-Asian tweets by one school board member, the Lowell High School changes, plus a surge in hate crimes against Asian people have galvanized that community.

A school board supporter, Julie Roberts-Phung, who co-chaired the no-recall effort, cites doxxing and harassment of people opposed to the recall. Pictures of two board members were painted with swastikas and burned, she says. This school board is the most credentialed, diverse board she’s seen – one that responded to parents’ concerns about pandemic safety.

“We have deep-seated issues around racism in San Francisco,” she says. “There’s a lot of people who describe themselves as liberals but are taking positions that are opposite of Black and brown families in San Francisco.”

The city is a hotbed of local politics, says Mr. Roberts, the former managing editor. “It’s kind of like Beirut. There’s so many factions. It’s bare-knuckled and in your face.” The issues being vigorously argued over today – education, public safety, homelessness, race – go back decades, he says.

In a way, today’s backlash could be described as a fight over how to be the most effectively compassionate.

“San Francisco is plagued with idealism. We really do want to care for everybody that can’t care for themselves,” former Mayor Willie Brown told The New York Times in January, when asked about the city suffering from a crisis on the streets. But that idealism has created its own set of problems, as anyone walking the streets of the Tenderloin can see.

Safe passage in the Tenderloin

It’s a bit like parting the Red Sea. For two hours every weekday morning and afternoon, JaLil Turner and his team of 15 to 30 volunteers make sure the sidewalk along Jones and Turk streets in the Tenderloin is clear of drug dealers, drug users, tents, and any other potential dangers, so volunteers can escort young children safely to and from Tenderloin Community Elementary School.

“Kids are coming through,” announce the escorts, as they roll out in teal-and-orange safety vests. If they see someone openly using or dealing drugs, the escorts ask that person to move to the other side of the street. There’s no belittling or talking down, says Mr. Turner, and if someone refuses, there’s backup – a police officer who walks the route and more safety “ambassadors” contracted by the city.

“Our group is essentially all things to help the Tenderloin,” says Mr. Turner. He manages the Safe Passage program for the Tenderloin Community Benefit District, a nonprofit that is deeply committed to this neighborhood of 50 blocks sandwiched between the luxury stores of Union Square to the east and the imposing beaux-arts City Hall, opera house, and symphony to the west.

This is the area that shocks Mr. Turner’s friends who visit from Kansas, where he went to college. The visible concentration of people struggling with substance use disorder, mental illness, and homelessness does not comport with their paradisal image of San Francisco. Also living here: the city’s largest concentration of children, 3,500 of them, as well as older adults, many of them Asian. “It’s a melting pot,” says Mr. Turner, with many young immigrant families from the Mideast and Latin America.

The Safe Passage patrols reflect that. Tatiana Alabsi, from Yemen, wears her safety vest over an abaya and hijab, and speaks Arabic. Her son goes to the school. Spanish speaker Maria Cortes, a volunteer from Mexico, has two boys in the school. The patrols start off from a sparkling YMCA in Boeddeker Park, with two “captains” peeling off at street corners along the route. Mr. Turner understands it can be uncomfortable for people to work in this area, but for him, it’s the opposite. His grandmother was a drug user who frequented the Tenderloin, and as a child, he and his mother would sometimes come here looking for her. He does this work “from the heart” to help others in a similar walk.

Mr. Turner walks the entire route, checking in by radio every 15 minutes with his crew. Along the way, he points out fresh murals in the neighborhood, a small Yemeni eatery where he sometimes gets lunch, a street sanitation crew, and a gated corner park in pristine condition. The cleaned-up park is another improvement since the state of emergency, maintained by his nonprofit’s staff. He also passes a man behaving erratically, a sidewalk party, and at an opposite corner close to the school, drug dealing. About a dozen young people are milling about there. Which one is the drug dealer? “They all are.”

In his three years doing this work, he has observed the stark contrast between policing and conditions in the Tenderloin and everywhere else in the city. Residents here vigorously protest the way that homelessness and drug use have been “contained” in their neighborhood. Behaviors are “allowed to happen here” that are not tolerated elsewhere, says Mr. Turner.

“If you’re selling drugs in the Presidio and you’re caught, you’re usually arrested and prosecuted. You’re not out in a day or so. You do it in the Tenderloin, and that same person you saw dealing, who was arrested in front of your eyes yesterday, will probably be out tomorrow.” It’s not unusual for him to see Tenderloin dealers commute from Oakland with him on Bart. “If you’re a drug dealer and you can go to a place where you won’t be prosecuted, you’ll probably go there every day.”

On this day, walking along Turk Street, he was pleased to point out two police officers on motorcycles – another novelty since the state of emergency, he says. Meanwhile, the nearby shopping district of Union Square is bristling with seven marked police vehicles, plus a trailer-sized emergency operations center, on the block where the Louis Vuitton store is located. In November it was hit with a sensational “smash and grab” robbery.

At 2:40 p.m., the Tenderloin school begins the coordinated end-of-school routine. Six groups of kids are released at intervals over the next half hour. They make their way down the Turk Street sidewalk, masked and toting backpacks, a Safe Passage worker leading the way and another one bringing up the rear.

Now in its 13th year of operation, the entire Safe Passage effort is finely tuned. That’s a point of pride for Mr. Turner. But he also comments that the best thing for a nonprofit is to no longer be needed. “I feel like I will never not need to be here.”

Time for “tough love?”

In November, the Tenderloin Community Benefit District wrote to Mayor Breed pleading for help. Families met with her, describing daily dangers that they and their children encounter on filthy streets.

The intensity of challenges seemed to reach a boiling point in December when the mayor, citing persistent, worsening public safety and an opioid crisis with an average of two overdose deaths a day, declared a state of emergency in the Tenderloin. It allowed for more enforcement and disruption of illegal activities, and cut through red tape to stand up the Tenderloin Linkage Center – a one-stop resource for people who need health, housing, or social welfare services.

“I know that San Francisco is a compassionate city. We are a city that prides ourselves on second chances and rehabilitation, but we’re not a city where anything goes,” she said.

The mayor, whose sister died of an overdose, said she was raised by her grandmother to believe in “tough love.” Described as a moderate, she is often at loggerheads with the progressive board of supervisors. She supported the recall of all three school board members and recently said that she is “not on the same page” with District Attorney Boudin.

“I think we’re sort of suffering the effects of what people have called progressive policies that have been in place for many years but in fact don’t really serve the very people they are purporting to serve,” says Maggie Muir, a Democratic consultant in San Francisco.

The tussle over policies comes into sharp focus at the new Linkage Center. On one hand, it’s being praised for bringing siloed agencies together under one roof and making them easy to access. It’s located at U.N. Plaza, across the street from a “safe sleeping” homeless encampment in front of City Hall. A man emerges from the center and happily says people there were able to connect him with temporary housing. He’s been homeless and fighting substance use disorder since he was let go by the National Park Service two years ago.

But the center has come under sharp criticism for a fenced-in, outdoor area that allows “safe use” of drugs, denounced by some as enabling users. Outside the center, a few men lean against the building, one of them holding a makeshift pipe to his face – the kind often used to smoke fentanyl, crack, or crystal meth. A young man walks up to people loitering outside the center’s entrance, announcing, “I got meth. I got crack.”

Open dealing and use without consequences “create an environment where people get caught in an endless cycle of addiction without actually getting the help they need,” says Ms. Muir.

At the state level, Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom has said he wants to make conservatorship easier for homeless people “who truly can’t help themselves.” That’s something that would have to go through the state Legislature and is sure to face stiff opposition from civil rights advocates.

On criminal justice reform, Ms. Muir points out that San Franciscans have consistently elected progressive, reformist prosecutors – the question is, what does reform look like? Mr. Boudin narrowly won in 2019 on a campaign of ending mass incarceration and holding police accountable. But Ms. Muir faults him for releasing people from jail without a real assessment of whether that person has a support network to prevent him from reoffending. Criminal justice reform and public safety “should be able to work together.”

And on housing, many cite a resistance to new projects. Progressives object to market-based housing, while residents on the west side oppose higher-density dwellings.

Del Seymour lived in the Tenderloin for more than 30 years and is deeply involved in neighborhood issues through his nonprofit, Code Tenderloin. He guffaws over the premise that San Francisco is a liberal city. “That is the biggest San Francisco myth of anything,” he exclaims. “These people are so holier-than-thou,” he says of the NIMBY crowd. “It went from Summer of Love to not in my backyard.”

He would welcome a city that is much more liberal – with mental health services in place of the Tenderloin’s 40-plus liquor stores, for instance. And he doesn’t want to see a greater police presence. “We don’t need no more stinkin’ badges down here,” he says, citing heavy-handed law enforcement. “We manage ourselves pretty well.”

He’s unhappy that the mayor declared a state of emergency, calling it a matter of “dignity.” The crisis in the Tenderloin is decades old, he said. “The only thing that’s changed is the model of the cars.”

And yet, he’s pleased with the new one-stop Linkage Center. He’s also pleased that the city is buying buildings, such as a hotel, to shelter homeless people. Earlier in the pandemic, about 400 tents blocked sidewalks in this compact district. Now, it’s down to about 40 – not counting the encampment, according to the district supervisor’s office. “Things are looking up,” says Mr. Seymour. “I can see light at the end of the tunnel, and it’s not a train.”

If there’s anything good about the pandemic, he says, it’s that “finally the homeless are coming into focus.”

Indeed, the pandemic has stirred things up in this city. Unlike in Congress, no Republican threat will force the hand of leaders here. It’s Democrats themselves who are left to work their way through these complex challenges, toward the sweet spot where compassion meets effective governance.