Ukraine attack: Putin target may be democracy, near and far

Loading...

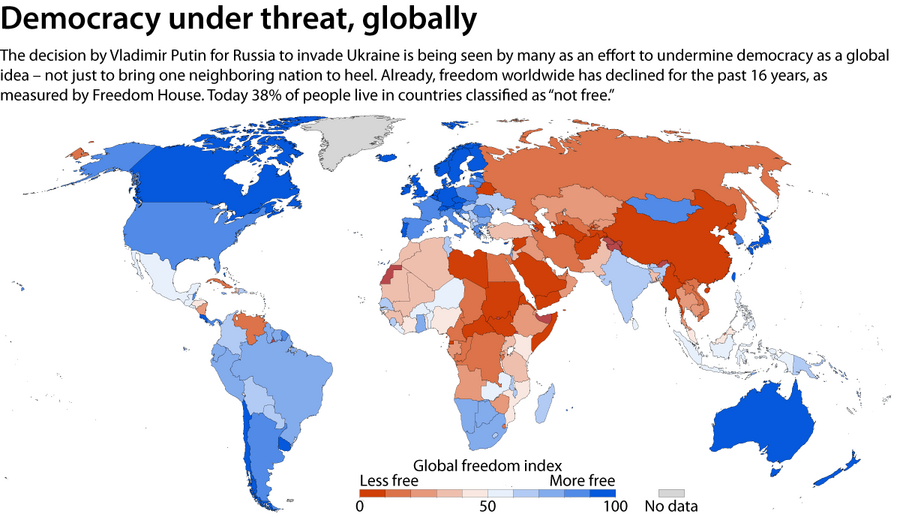

In launching a brutal, unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, Russian leader Vladimir Putin is attacking not just a sovereign nation but the very idea of democracy – Ukraine’s, and America’s.

Democracy poses a dire threat to Mr. Putin, after all. Ukraine’s democratic history is far from perfect, yet the existence of a functioning elected government on Russia’s border, in a country that used to be a Soviet republic, could make ordinary Russians whose electoral choices have been constrained in recent years wonder: If ballots work in Kyiv, could they not work again in Moscow, too?

At the same time, Mr. Putin may have seen problems in Western democracies as an opportunity. In the United States, electoral democracy is showing cracks as voters polarize and former President Donald Trump’s false claims of a stolen election spread through the Republican Party. In France, Germany, and other Western European states, far-right parties have gained ground in recent years, and white supremacist populist beliefs are on the rise.

Why We Wrote This

It is a paradox of democracy that it can seem both weak and threatening at the same time. Whatever challenges democracy is facing, a Slavic version may have appeared undesirable on Russia’s border.

Put these perceptions together and a war of choice may seem like a solution. Mr. Putin has professed many justifications for Russia’s assault on Ukraine, from wild claims about ‘de-Nazifying’ the country to anger at Kyiv’s desire to join NATO, the Western treaty alliance. Another might be that Mr. Putin and other top Russian officials believe it’s a way to highlight the weaknesses of democratic systems and the vitality of an authoritarian axis of Russia and China – while ridding Moscow of an inconvenient neighbor.

“Putin himself has promoted an idea that the East has different values than the West, that they have different notions of democracy than the West, that his version of autocracy, along with [Chinese leader] Xi Jinping’s, is a cultural norm,” says Derek Mitchell, president of the National Democratic Institute.

Ukraine’s record

Ukraine’s government is clearly a central target of the Russian attack. At the time of writing, reports indicated that Russian troops had entered the capital of Kyiv from the north, and Ukrainians were bracing for a violent battle for the city. There were inconsistent reports of a Russian willingness to negotiate with Ukraine.

Russian officials have charged Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and his cabinet with being “militaristic,” “neo-Nazis,” and most of all, stooges for “American lies.” The Russian Foreign Ministry has said one of the aims in invading Ukraine is to “bring the current puppet regime to justice.”

Ironically, when the Soviet Union crumbled in late 1991, American officials worried about the implications of Ukraine completely severing ties with Russia. Their economies were so intertwined that such a move could be “disastrous,” wrote National Security Adviser Brent Scowcroft in a memo for President George H. W. Bush.

But events moved too fast to avoid that eventuality. Ukraine held a referendum on independence on Dec. 1, 1991, that passed overwhelmingly. At the end of that month, the Soviet Union officially dissolved.

For 30 years since, Ukraine – the largest country by land mass within Europe – has struggled to build a democracy. Its democratic institutions are not yet fully free and fair by Western standards, despite the ouster in 2014 of the Russian-leaning former president, Viktor Yanukovych, after widespread civic protests.

Corruption remains endemic, and efforts to combat it have met resistance, according to Freedom House, a nongovernmental organization that studies human rights and democracy around the world. Attacks against journalists and civic activists remain frequent.

But elections for president and legislative representatives have lately been almost entirely free. Freedom House gives Ukraine an overall “global freedom” rating of 61 on a scale of 100.

While Ukrainian democracy has had some problems, “we are still an electoral democracy with fair elections,” said former Ukrainian Prime Minister Oleksiy Honcharuk in an interview on the Stanford University “World Class” podcast last December with former U.S. Ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul.

And for the Kremlin, it is dangerous to have even somewhat successful democracies close by, especially in Slavic, Orthodox Christian countries with close Russian ties, said Mr. Honcharuk.

For Mr. Putin and his cronies “it’s very important that the Russian people believe that democracy is a weak idea and is a failing idea, and that democracy doesn’t work for Russia ... or at least doesn’t work for the region,” Mr. Honcharuk said.

If Ukraine, as Mr. Putin says, is culturally Russian, then a pro-democracy Ukraine is indeed a threat to Russian autocracy, adds Mr. Mitchell of the National Democratic Institute.

“It’s very clear that he’s ... threatened by the unity and the democratic orientation of Ukraine,” he says.

Democratic backsliding

Mr. Putin may also have seen military action as a viable answer to his Ukraine problem due to the deterioration of democratic politics in the United States and other Western nations.

The rise of white supremacy groups, increased anti-immigrant sentiment, and the election of leaders who focus only on their own voting base have contributed to a growing expansion of “homegrown illiberal streaks” within democracies, concludes Freedom House’s Freedom in the World 2022 report.

Russia has long sought to widen these cracks in the West via such disinformation efforts as its meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Disunity at home could sap the will of the U.S. and its allies to act abroad in defense of democratic values, in the view of Kremlin leaders.

The conflict in Ukraine, regardless of what happens, is emblematic of the democratic backsliding that’s been occurring in nascent and established democracies – and of the strengthening of authoritarianism in Russia and China, says Pippa Norris, a professor of comparative politics at the Harvard Kennedy School who focuses on democracy, public opinion, and elections.

Competition between these forms of government moves in waves, Professor Norris says. Democracy rose before World War I and fell after with the rise of fascism. It rose after World War II and then fell again in the 1970s. It rose a third time with the fall of dictators in Greece, Portugal, Spain, and other countries.

“Now we’re seeing, essentially, the third reverse wave,” she says.

Given democracy’s troubles, the most notable thing about the response to Mr. Putin’s aggression against Ukraine may be how unified it has been so far. Professor Norris says it is especially surprising given the transatlantic divisions caused by former President Donald Trump, who harshly criticized the NATO alliance, and the reputational damage suffered by the U.S. after its chaotic pullout from Afghanistan under President Joe Biden.

“In this particular case, the amazing thing is how far Europe and America are falling into one voice and how they’ve all come together,” she says.

Eastern Europeans’ efforts

For more than a decade, Mr. Putin has carried out a salami strategy against Ukraine – carrying out his plan in small slices that individually haven’t merited a massive Western response. Russia has faced only limited consequences for such actions as its seizure of Crimea in 2014 and its continuing support of separatists in Ukraine’s Donbass region.

Limited consequences, until now. Since late last year, Western democracies have led an intense, coordinated diplomatic response to Russia’s build-up of troops around Ukraine, says Damon Wilson, president and CEO of the National Endowment for Democracy.

“This is just night and day between the reactions that Putin has faced in previous cycles, because we’ve learned if you don’t stop him, his appetite grows and he goes for more,” Mr. Wilson says.

Sanctions are only one part. The U.S. has also responded with troop deployments in Eastern Europe and the Baltic states intended to deter even further aggression.

Mr. Wilson says Putin’s aggression has in fact unified Ukraine, NATO, and even the U.S. itself. While there are some conservative voices questioning whether America should care about Ukraine and even praising Mr. Putin’s actions, the vast majority of both parties have denounced Russian aggression in no uncertain terms.

“There’s not really a big debate here,” says the National Endowment for Democracy president.

People in Eastern Europe are leading their own efforts to become democratic societies, he adds. They’re not being pressured or coerced by the U.S., the EU, or NATO.

“We can’t pull our punches or support for the aspirations of people who want a democratic future,” he says.