Rebels with a religious cause: Meet New York’s avant-garde conservatives

Loading...

| New York

Jordan Castro looks with wonder at the audience gathered at Earth, an underground literary salon in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. About 300 people have packed the place to hear the young novelist talk about his work.

He’s long been an alternative-literature darling, too. He was the editor of New York Tyrant Magazine, an avant-garde publication specializing in experimental writing. He’s also a traditionalist who fell in love with the Eastern Orthodox liturgy and converted a few years ago. He says faith freed him from moral rot and a past life consumed by heroin addiction.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onNew York has long been a haunt for underground artists. A growing number have become more conservative – and religious.

“Christianity has taught me to pay attention to the important things. I love Jesus, man,” he says.

Mr. Castro is part of a new conservative avant-garde that has been emerging in lower Manhattan since the pandemic – the same area where punk music, beat poetry, and edgy, transgressive art has long flourished. These hip New York creatives have been trying to liberate themselves from the ideological shackles of the dominant progressive left.

Writers, filmmakers, and fashion designers have been dabbling in pre-Vatican II Catholicism. They play the church organ rather than DJ at nightclubs. Instead of free love and polyamory, they espouse commitment and monogamy.

“People are tired of pure secularism. It’s a dead end. It doesn’t promise anything,” says Stephen G. Adubato, a writer and professor who’s also active in this conservative avant-garde art scene. “But I am seeing more people being drawn to organized religion.”

Salomé slides her svelte figure through a cracked-open double door near the front of the dark sanctuary.

Click clack. It’s the first moment of the vigil of Easter at Church of the Most Holy Redeemer in Manhattan’s East Village. Worshippers at this historic Catholic church can only hear her stiletto heels, faint and staccato, as she walks to its organ.

She steps carefully up the old stone steps to the console, flicking on a reading light that illuminates her sharp features. As more parishioners walk in, she begins to play a mournful introduction, marking the last moments of Lent in what is now a quiet cacophony of footsteps.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onNew York has long been a haunt for underground artists. A growing number have become more conservative – and religious.

This is the organist’s sixth gig in four days during Holy Week, which she says is “kind of fashion week for Catholics.” A classically trained musician, she is also an artist and model. Earlier this year at an uptown literary ball, she walked a runway for Elena Velez, a well-known designer who’s been called the enfant terrible of the fashion world, modeling her controversial “Gone With the Wind”-inspired clothing line during the actual New York Fashion Week.

The church is tucked into a street of 19th-century tenements between Avenues A and B in the East Village, a neighborhood that once embodied New York’s bohemian clichés. Right next to it is Graveyard NYC, a heavy-metal tattoo parlor. A few blocks away, the legendary CBGB nightclub, shuttered in 2006, was one of the birthplaces of punk. In 1990, local artists and musicians staged a legendary Resist 2 Exist festival in nearby Tompkins Square, then a drug market and homeless tent city, sparking a near riot when police shut it down.

The neighborhood may have long since gentrified, but Salomé, her confirmation name-turned-celebrity mononym, has been part of a new cadre of young New York artists who have been raging against a different cause: the cultural rot and decadence brought about by “libtards.”

“Leftists see greatness, and they see beauty, and they’re threatened by it, and they want to destroy it,” says Salomé, who says the Tridentine Mass is “the greatest work of art” for its superior musical composition.

Originally from Philadelphia, Salomé has been a devout Catholic since she was young. She wears a “Make America Great Again” hat around town sometimes as an act of ironic defiance. And even though she’s a transgender woman, she prefers the term of an earlier age: castrato.

But first and foremost, she says, she’s a child of God.

“I’m just Catholic here. I sort of refuse to identify myself with any other label, gender, sexuality, political,” Salomé says. “I’m Catholic, and I’m an artist. And so because I’m an artist, I’m interested in all ideas. And I happen to have been born in a time when that is not OK.”

Clack. Click. At the end of the service, Salomé steps into the vestibule’s yellow light, her 3-inch black pumps clearly visible now. It’s late in the evening, but she’s wearing a pair of chunky onyx sunglasses that hide her piercing blue eyes, eyes that have locked with French creative directors as well as Italian priests during confession. A wrinkleless, stone-colored Prada trenchcoat presses tightly against her frame.

Parishioners exit the church making their last signs of the cross, and Salomé click-clacks quickly down Third Street, disappearing into a crowd of 20-something pleasure-seekers in the East Village’s array of cannabis shops and street vendors. She’s heading toward the heart of lower Manhattan’s conservative counterculture, an area near Chinatown recently dubbed Dimes Square.

“New York’s hottest club is the Catholic Church”

In many ways, the Dimes Square scene began when young New Yorkers, skaters and creative types sick and tired of pandemic restrictions, began to rebel.

Some embraced virtual environments and the technology that made them possible, and edgy podcasts and snarky Substack blogs have always been part of the scene’s driving force. But a good number of New York youth saw art and literature as something meant to be shared in person.

Maskless parties started up. A playwright and conservative magazine contributor began staging his work in living rooms. A new local newspaper/neighborhood bulletin called The Drunken Canal began documenting the punklike disregard among local youths for Dr. Anthony Fauci’s rules.

“Young people want presence,” says Tara Isabella Burton, a bestselling novelist and Oxford-trained theologian. “It’s normal, what’s going on. It happened in the 19th century where you saw dandies rebel against automation and industrialization, which affected the politics and the aesthetics of the time.”

The restaurant Dimes at the corner of Canal and Division streets near Chinatown became a haunt for an array of hip New York creatives seeking to liberate themselves from both social and ideological shackles. As a pun on Times Square, the gritty area at the border of the Lower East Side became known as Dimes Square.

“I certainly don’t need to tell you that this place is also, emphatically, not in Brooklyn,” wrote the leftist Substack blogger Mike Crumplar in 2022, with a bit of snark. “You already know how Brooklyn is too political, too woke, too soft, too soy, too consumed by cancel culture to be a fertile climate for artistic expression. You’ve already heard about how the vibes are shifting back to downtown Manhattan, which is grittier and sleazier. It’s a place where older literary men can have younger muses, free from the prudish Robespierres of the North Brooklyn [Democratic Socialists of America].”

The podcast “Red Scare,” begun in 2018 and hosted by cultural critics Dasha Nekrasova and Anna Khachiyan, was among the first to popularize the term “Dimes Square.” Associated with the “dirtbag left” – a term that described zealous Bernie Sanders supporters who eschewed civility and prioritized disruption – the hosts later became disillusioned by the movement and explored the ideas of the “new right,” the Donald Trump-led movement that also stands against neoliberalism, global capitalism, and corporate hegemony. Their guests have included people such as Steve Bannon and Alex Jones.

Ms. Nekrasova is also a devout Catholic, even if she likes to quip, “Catholic, like Andy Warhol.” An actor who had a recurring role in the popular HBO series “Succession,” she has hosted podcasts on obscure theological topics.

“People accuse me of being fascist or a cultural conservative,” she says in an interview. “I actually feel more like a degenerate artistically. ... I’m a free speech absolutist.”

Both she and Ms. Khachiyan have been outspoken against what they see as the godless politics of the left. “No hell, no dignity,” Ms. Nekrasova once said.

Partly because of their influence, the Dimes Square scene began to include a number of artists with more conservative and religious visions. Writers, filmmakers, and fashion designers have been dabbling in pre-Vatican II Catholicism. They play the church organ rather than DJ at nightclubs. Instead of free love and polyamory, they espouse commitment and monogamy. And the flip phone is a favorite accessory – a statement against the herd and its iPhones.

“New York’s hottest club is the Catholic Church,” proclaimed Julia Yost, senior editor at First Things magazine, in a 2022 essay in The New York Times. “Traditional morality acquired a transgressive glamour,” she wrote of the Dimes Square scene. “Disaffection with the progressive moral majority – combined with Catholicism’s historic ability to accommodate cultural subversion – has produced an in-your-face style of traditionalism.

“This is not your grandmother’s church – and whether the new faithful are performing an act of theater or not, they have the chance to revitalize the church for young, educated Americans.”

A literary salon for the 21st century

Jordan Castro looks with wonder at the audience gathered here at Earth, a literary salon and gallery on Orchard Street in the Lower East Side. About 300 people, mostly young and many dressed in monochrome cool, have packed the place to hear the young novelist talk about his work.

Earth’s literary salon has been attracting large crowds of people drawn to a literary scene known for its critiques of liberal hegemony in the arts. Its readings and discussions often feature writers who present ideas with witty and at times caustic, ironic prose.

Mr. Castro has long been an alternative-literature darling, too. He was the editor of New York Tyrant Magazine, an avant-garde publication specializing in experimental writing. Rugged with wild brown hair and kind, dark eyes and wearing an olive fatigue, he wrote an essay in Harper’s Magazine on body building that went viral. He’s like a Christian Ken Kesey with a neck tattoo of Ohio, his home state.

“I think for me, the best literature ... can kind of reveal aspects of life or reality or the psyche or the soul that can reveal those things in sort of unique and compelling ways, so that we can kind of become more attuned to our condition,” Mr. Castro says in an interview. His first book, “The Novelist: A Novel,” is considered a work of “autofiction,” and has received glowing reviews.

The room is hot, so the door stays open as the overflow builds just outside the gallery’s storefront space. A young woman peers inside on the shoulders of a friend or lover. An imposing figure whose head practically met the ceiling just outside the door scans the crowd looking like Jesus. Some stray voice in the crowd calls him “LePuff.” Young people in grunge-inspired fits and fashion-forward couture squeeze into the corner by the refreshments.

Other readers include the doyenne of Dimes Square, Ms. Nekrasova of “Red Scare,” and Tao Lin, another autofiction writer. Mr. Castro’s wife, the writer Nicolette Polek, hosted a reading a month ago from her new book, “Bitter Water Opera,” which The New Yorker magazine called one of the best books of 2024.

True monogamy and traditional Christianity are the last taboos to many, says Mr. Castro, who fell in love with the Eastern Orthodox liturgy and converted a few years ago. He explains how true faith and love freed him from moral rot and a past life consumed by heroin addiction.

“I strive to be undistracted,” he remarks. “Christianity has taught me to pay attention to the important things. I love Jesus, man. Especially when he’s ranting at the spoiled temple in John.”

He reads poems and stories with a charisma that beams through his smile. The crowd giggles at his insights and claps louder at his lyrical flourishes. Often awkward around strangers, he is comfortable on this makeshift stage. “Trad culture is not bad for you. Neither is having an objective standard of meaning and not wanting to sleep with 10,000 people,” he says.

As a writer and artist, Mr. Castro believes the power of literature can be an entryway into deeper faith – the same theme his wife, Ms. Polek, pursues in her fiction.

“I think that when people get rid of a transcendent standard of meaning – you know, get rid of a sort of idea of a truth that we can all agree on, something that sort of transcends our own individual whims or preferences – I think when you get rid of that power, it’s sort of just your will versus my will.

"And then, you know, if we’re going to live harmoniously, harmoniously with each other," he continues, "we have to have something that can unite us, that sort of transcends our desires, which can change at any moment and which are sort of, you know, untrustworthy.”

A taboo against taboos

Click clack. Salomé steps into the screening room of Sovereign House, a subterranean loft and underground artists space in Chinatown.

She’s wearing a sheer black gown and an Arctic fur stole, and she holds aloft a bouquet of roses and baby’s breath. Fans gather in a circle to greet the musician and model. She’s a well-recognized presence in the Dimes Square scene. It’s a screening for her most recent creative turn: She acted in a short film titled “Envy/Desire.”

“We’re just kind of reinventing, like, how do you make a movie?” Salomé says. “It’s made by someone who’s not a filmmaker, and acted by people who are sort of not actors. Yeah, it’s like a new thing. It’s not so much like an intentional, ‘Oh, we’re going to do this because we’re going to insert this belief.’”

The film recalls the do-it-yourself quality of a John Waters film, and it’s about a transgender woman who believes she may have found the man of her dreams. But his interest in her may reveal his own questions about his gender. Afterward, the crowd claps for the creative team as it takes bows under warm stage lights, and many linger for the Q&A.

Sovereign House is a salon started by Nick Allen, a New York tech worker who wanted to create a space for more dissident Dimes Square artists. They host parties for newly launched magazines, stage new plays, and even just engage in conversations about art and literature. (The tech entrepreneur Peter Thiel has also helped fund an “antiwoke” film festival in Manhattan.)

The underground event space has rustic columns separating the foyer from the screening room area. Ironically, the patio out back overlooks the headquarters of the Democratic Socialists in New York.

A general vibe in Dimes Square is that no ideas are off-limits – a reaction to what many artists see as the stifling censorship of left-wing “cancel culture.” The salon at Sovereign House has hosted speakers such as Steve Sailer, a far-right thinker. In the past, Mr. Sailer has said Black people “possess poorer native judgment than members of better-educated groups” and need moral guidance from society.

But the underground salon in Chinatown has also included a number of religiously conservative artists and thinkers.

Bucking against convention

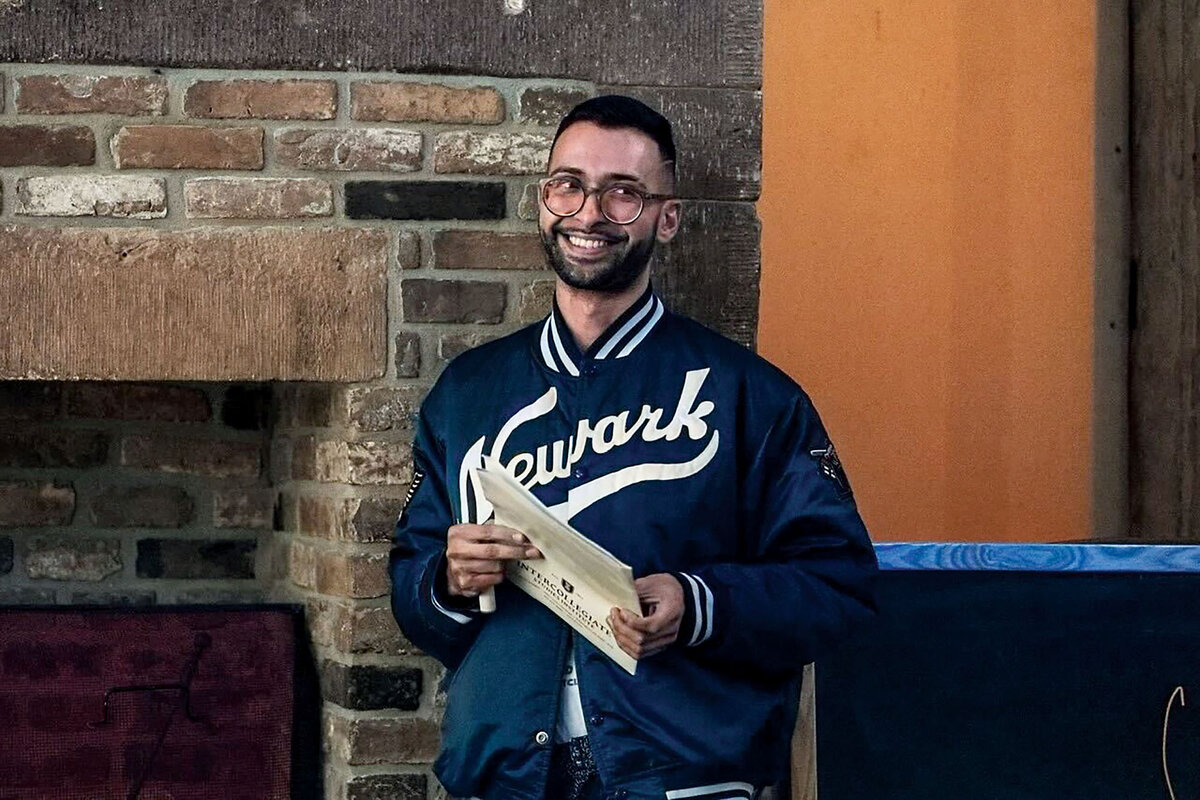

On a cold October night last fall, Stephen G. Adubato was chatting up guests at Sovereign House while wearing a “Newark” patched bomber jacket and sporting a freshly cut fade. Around his neck is a gold cross – the writer and professor of philosophy and religion is a devout Catholic.

He’s here to talk about the latest issue of his project Cracks in Postmodernity, which includes a Substack, zine, and podcast. It’s been catching on with a downtown set of writers, and a big crowd has gathered to hear him read from his latest issue.

The master of ceremonies for the evening, Brennan Vickery, a local bartender who is a regular presence at Sovereign House, contributes to Mr. Adubato’s project. He warms up the crowd.

“Alex Jones, who I by no means am a fan of, but he said this thing that kind of stuck with me, and it is kind of true,” he says afterward. “He’s like, Do you want to go to a house party that’s with liberal people or conservative people? If you go to a liberal party these days, it’s like, you can’t say this, you can’t say that. ... It’s going to be subdued. No one can be offensive. So who do you want to party with?”

Like Salomé, Mr. Adubato only accepts the label Catholic. He says he does not consider himself a conservative, per se, but he accepts the full moral teachings of Catholicism. He initially said his project was intended “to explore the ways that our contemporary culture points us to the truth of Christ.” He changed it to an edgier description: “subverting subversiveness through pretentious and ironic cultural commentary that gives precedence to aesthetics and ontology over ethics and politics.”

“I don’t want anyone to say anything conventional,” Mr. Adubato says in an interview. “I don’t want anything predictable. I don’t want anyone to sound like they’re reading off of a script. That being said, I also think there’s a certain limit. I like to be risqué. I like to poke fun at conventional discourse. I’m trying to serve a higher purpose. There’s a point where it could become self-indulgent. Where you can say something very hurtful to somebody.”

He’s nervous tonight. Onstage in a pair of white Nikes, he shakes a bit with his eyes glued to the pages in front of him – a short story about a blue-haired liberal “getting owned” by a believer in the Almighty.

Mr. Adubato has been visiting other downtown venues to publicize his project. At another event at The Catholic Worker Maryhouse on Third Street in the East Village, not far from Church of the Most Holy Redeemer, over 120 people come on a cold Monday night.

He discusses the growing interest in religion in these downtown Manhattan haunts.

“People are tired of pure secularism. It’s a dead end. It doesn’t promise anything,” he says in an interview afterward. “There are people who are still into this spiritual thing and not being tied to any institutional religion. Some people are still into the new age stuff, which in a way has a value. I get why people are still drawn to it.

“But I am seeing more people being drawn to organized religion, whether it’s Catholicism or branches of Protestantism or Islam or Judaism, because there is something a little more concrete about the promises that practicing these religions gives you.”

The communal spirit at these events focusing on religious issues has been growing.

“When you go to a church, it’s very clear what’s being asked of you, and you can share that path with other people. We want that. We want to be together,” says Mr. Adubato. “We want to understand what our lives are for. We don’t want this vagueness anymore.”

In search of community

Audrey Horne hangs her winter coat on the wicker chair before she sits down to a hot cup of coffee at Café Kitsuné in Manhattan’s West Village. Her blue eyes scan the Saturday afternoon crowd. In the corner, a man in a two-piece suit adds final touches to a fashion sketch in front of him, an emerald-hued pastry reduced to crumbs beside him.

She’s made a name for herself as a writer and thinker simply by posting on online forums and the social media site X, where she has 32,000 followers, including editors and writers from Harper’s and The New Yorker.

She spends a lot of time in Washington, D.C., where she’s become part of a similar scene of religious thinkers and seekers meeting to discuss art and literature. But she remains a voice in the Dimes Square crowd.

“I kind of grew an audience through fighting people online and telling people how lonely I was, and just being really brutally honest,” she says. “People responded to that in a really unprecedented way.”

Sitting upright, Ms. Horne doesn’t telegraph “bohemian layabout.” But her attendance at downtown readings and literary salons speaks to the curiosity that had remained unquenched in her youth. She spent much of her childhood in the Two by Twos religious sect, witnessing an FBI raid on what has been labeled a cult. She now says she’s a nondenominational Protestant Christian.

She was living in Seattle before the pandemic, and she describes how she became weary and even a bit alienated from the politics of women’s marches, liberal arrogance, and political correctness.

“And then I listened to this podcast from New York, ‘Red Scare,’” she says. “It was really exciting, because these are women who historically, I would assume, would be totally opposed to me. But they were saying things I kind of felt and agreed with deep down. ... At the time, there was, like, a sense of almost revenge, and it was kind of delicious. Yeah, I was just intoxicated.”

So she moved to the East Coast – just before the COVID-19 shutdown. Isolated and lonely, she began to get into arguments online in the style of “Red Scare.” As she got noticed, she started getting out and hitting up Dimes Square watering holes, where she met up with like-minded artists rebelling against what they saw as liberal hegemony. For the first time, she felt comfortable in a secular world of artists and bohemian layabouts, bon vivants, and culture vultures.

But all the aggressiveness and snark and irony now seems to have gone too far in the scene, she says.

“I’ve had to learn to hold a lot of complexity,” Ms. Horne says. “And that has made me, I think and I hope, far less judgmental, far more open, and far more forgiving of myself and of others and their forms of exploring.”

Part of this spirit of tolerance, she says, is arising out of many people’s earnest search for meaning. And a lot of that has to do with a growing interest in religion. “There’s something in the air right now that does feel much more open to faith,” says Ms. Horne. “I think that culture now feels a lot more – a lot softer, like people are curious about it and seeking it. And not just seeking it, but the real truth underlying the life of faith. ... It has made space for me to jump in and express what I believe to be true.”

“We want something pure. We want something earnest,” she continues. “I hate to say a new sincerity, but it feels like a return to sincerity. I do think that that’s what feels most fresh right now [in the arts]. Like, it’s not even funny to be anti-irony. Like, just don’t even reference yourself; don’t talk about postirony, post-culture war. That’s what we’re kind of tired of.”

A sense of belonging

Mr. Vickery, Cracks in Postmodernity’s emcee, is standing outside the salon, hanging out near Sovereign House with a crew of bushy-haired 20-somethings. The conversation turns to the place of gay men in the LGBTQ+ community.

Despite being gay himself, Mr. Vickery says gay men are not really a part of this “intersectional” identity. “We’re different historically,” he says.

He never felt he fit in with the other tribes of gay men clustered in Hell’s Kitchen and Chelsea on the West Side, those who were onto “a new cause every week.”

“I think the reason that [artists here] are socially conservative – or at least they pretend to be in this punk kind of element – is because they don’t want to be told what to do and what to make and what not to say.”

He tried his hand at acting and painting and publishing after he left the Florida Panhandle for New York, and he grew at odds with a lot of the decadence and ugliness in the city, he says. But he fits in here with aggressive, free-thinking conservatives.

“A lot is so dirty and confusing now,” Mr. Vickery says. “People want order. They want something beautiful. But will this scene live on? Will the ideas matter? I’d be interested in seeing if it’ll have an effect.”

Editor's note: This story has been edited to correct Ms. Khachiyan's religious status.