Mandela's conscious role became that of national storyteller

Loading...

| Johannesburg, South Africa

In August 1995, just a year after South Africa's first fully democratic election, President Nelson Mandela made an unusual social call.

Stepping off a helicopter in the windswept town of Orania, 400 miles southwest of Johannesburg, he knocked on the door of 94-year-old Betsie Verwoerd. Her late husband, former Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd, was known as the “architect of apartheid." Mr. Mandela had come to the Verwoerd home for a cup of tea.

In the often surreal moments of that time, as social realities changed in ways no one could imagine, this visit was among the most unusual: Orania was a whites-only town founded in 1990 by right-wing Afrikaners just as the country around it braced for the transition to majority rule. Mandela had spent 27 years in prison under a system Ms. Verwoerd’s husband had pioneered, and now he was calling on her as the nation's first black president.

In many ways, the moment was the epitome of what South Africans found most disarming – and at times most galling – about Mandela: his unswerving commitment to racial reconciliation, particularly in the places where it seemed least deserved.

Mandela's message to his political enemies was always simple, remembers his friend and fellow anti-apartheid leader, Ahmed Kathrada: “Work with us… You don’t have to join the ANC [the ruling party]. The first priority is to build a new nation.”

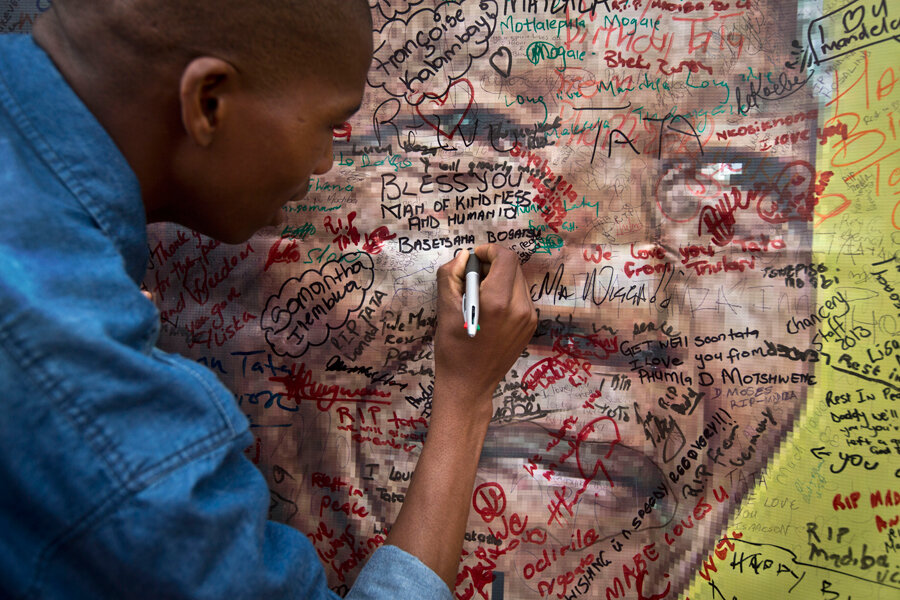

And as South Africans struggled in ways great and small to shape that country, Mandela’s conscious role became that of national storyteller – the man who would act out everything he hoped South Africa could someday be.

“He’s sewn into the fabric of what South Africa is,” says Ferial Haffajee, editor-in-chief of City Press, one of the country’s largest newspapers. “I don’t think we know how we’re going to understand ourselves without him alive.”

On a continent known for earnest revolutionaries who often turned into ironed-fisted strongmen – Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe, Angola’s Jose Eduardo Dos Santos, Libya’s Muammar Qaddafi – Mandela walked a new line. He shared a Nobel Prize with F.W. de Klerk, the head of the government that jailed him for nearly three decades, advocated and granted amnesty to many of apartheid’s henchmen, and stepped down after only a single term as president.

Mandela's life spanned nearly a century of South African history, and in many ways it was also his own story – the rural African from a far-flung corner of the former British empire who rose to become a lawyer, activist, political prisoner, and, finally, president of a majority-ruled nation.

Known to the world by his English name, Nelson, in South Africa Mandela is often warmly called by his clan title, Madiba. It is a small reminder of the enduring closeness that many here feel toward their elder statesman, who always appeared in trademark brazenly-patterned batik shirts and spoke several of South Africa’s official languages in a slow, inflected baritone.

That grandfatherly relationship to the country helped Mandela push the notion that revolution and reconciliation were two sides of the same coin.

“He had an extremely deeply ingrained sense of etiquette and fair play,” says historian Tom Lodge, the author of Mandela: A Critical Life. “He always accorded space for his opponents to behave decently.”

The revolutionary and the reconciler

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was born July 18, 1918 in the village of Mvezo in what is now South Africa’s Eastern Cape, the child of a local chief. His political career began when, as a young law clerk in Johannesburg in the early 1940s, he joined the African National Congress, a political organization primarily made up of black professionals, which then had a decidedly "elite" character.

Over the next several years, he and other young recruits chipped away at the ANC’s eliteness, transforming it into a broad-based multiracial movement for the rights of South Africa’s African, Indian, and mixed race (or “coloured”) people, who together comprised more than 80 percent of the country's population.

But the movement had a formidable opponent in South Africa's white government. As an undertow of anticolonial impulses pulled much of the continent toward independence in the 1950s and early ‘60s, South African leaders responded with a vicious crackdown on their own country’s freedom movement.

In 1963, Mandela and several other members of the ANC’s leadership were charged with sabotage and attempting to violently overthrow the government. At the sentencing hearing the following year, Mandela delivered a now iconic speech describing the radical turn the movement had taken.

“Who will deny that thirty years of my life have been spent knocking in vain, patiently, moderately, and modestly at a closed and barred door?” he asked the court, before ending his speech with an unwavering proclamation.

“I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society,” he said. “It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

The court spared Mandela and the others, including Mr. Kathrada, the death penalty, instead sentencing them to life in prison.

Over the next three decades, Mandela would watch from behind bars as activists continued their assault on the system of apartheid from in and outside of South Africa. By the late 1980s, white rule sagged under the weight of both violent conflict sweeping through the country and international diplomatic pressure and sanctions.

Still, the country’s government kept a white-knuckle grip on power, seemingly impervious to the international disdain that churned around them.

So the world was stunned when, in February 1990, President F.W. De Klerk made the surprise announcement that he would release Mandela from prison, remove the ban on the ANC and other political groups, and begin negotiations with the anti-apartheid movement.

Building a new nation

In April 1994, nearly 20 million South Africans – most of them first-time voters – turned out at the polls to sweep Mandela and the ANC into power for the first time.

Then the real work began.

For his five-year term as president, Mandela presided over a young country tasked with the outsized job of reversing centuries of racial hierarchy overnight.

And he did so by playing to both the politics and theatrics of reconciliation.

He organized a truth and reconciliation commission, which offered amnesty to hundreds of perpetrators of politically-motivated crimes during apartheid. And he put on the green and yellow jersey of the Springboks, white South Africa’s beloved national rugby team, and cheered them to victory in the 1995 World Cup.

Ms. Haffajee, the newspaper editor, remembers that at the time, she and her fellow young radicals found the president’s reconciliatory posture cloying.

“I think my generation expected him to be radical,” she says. “He wanted us to go and watch rugby and at the time that was hugely inexplicable to me … it was the personal magnetism of the man that enabled us to take political leaps that [we weren’t] really that fond of.”

The job of equalizing a nation, however, was a Herculean task, and Mandela never had the stomach for many of the grittier tasks it demanded, says Rehana Roussow, a retired political journalist who covered the Mandela presidency.

“I feel that Mandela spent far too much time on building this rainbow nation, which was and still is a huge myth,” she says, describing his efforts as a series of gestures that often did little to dismantle the vast economic and political structures that animated apartheid.

"He was a brilliant symbol [but] a flawed hands-on president," she says.

The incomplete revolution

Indeed, in the years since Mandela was first elected, the skin color of the country’s elite has changed. But the gap between its rich and poor has actually grown wider. South Africa is now perhaps the single most economically unequal nation on earth and has one of the world’s highest murder rates. Ten percent of the population is HIV positive.

“We were no longer second-class citizens,” Kathrada says. “But, we also realized, there’s no dignity in poverty. There’s no dignity in hunger. There’s no dignity in unemployment.”

And though he will always be remembered first and foremost as the father of the nation, Mandela was no political saint, says Lodge, the historian.

“He was loyal to his comrades, sometimes to a fault,” he says. “He was willing to put people into powerful positions who were not simply incompetent but also dishonest. The current political back-scratching can be traced to Mandela’s time.”

Mandela married three times, most recently to former Mozambican first lady Graca Machel, and was the father of six children, three of whom he outlived. His eldest daughter, Makaziwe, died as an infant; his son Thembi was killed in a car accident in 1969, while Mandela was imprisoned; and another son, Makgatho, died of complications from AIDS in 2005.

In his personal life he is perhaps best remembered for his tumultuous second marriage to Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, whom he met when she was a young social worker in Johannesburg in the late 1950s. A fiery and controversial political activist in her own right, she became a leading figure in the student uprisings of the 1970s. At the time, Mandela was writing her regularly from prison, counseling her to find such inner qualities as simplicity, sincerity, and a "pure generosity," and to overcome hatred.

RECOMMENDED: Nelson Mandela and 'the foundations of one's spiritual life'

Yet later, as Mandela sat imprisoned at the end of the 1980s, she earned a reputation as an iron-fisted and often violent enforcer of loyalty to the ANC, at one point explicitly endorsing the practice of burning black apartheid collaborators alive using a tire soaked in gasoline (a practice known as “necklacing”). The couple separated shortly after Mandela’s release from prison.

He is also survived by Ms. Machel, his other three children, and a nation that he was the linchpin in building.

“When a man has done what he considers to be his duty to his people and his country, he can rest in peace,” Mandela said in a 1994 interview.

“I believe I have made that effort.”