As Kenyan troops retreat from Somali towns, fears of insecurity grow

Loading...

Kenya’s military forces withdrew from two towns in southern Somalia on Tuesday, a move seen by many as a blow to Kenya's efforts to create a buffer zone between the Somali-based militant group Al Shabab and its border.

The retreat from El Adde and Badhadhe comes over a week after a deadly attack on the Africa Union (AMISOM) base in El Adde by the Islamist group.

Kenyan officials have been tight-lipped about the death toll, vowing to release the figure after they complete an investigation. But Al Shabab claimed that about 100 people were killed in the Jan. 15 attack, making it the deadliest incident involving Kenyan troops since they entered Somalia in 2011. A special memorial to commemorate the attack is scheduled for Wednesday in Kenya.

The timing of the troop withdrawal is significant. It comes just as Kenya is entering its fifth year in Somalia as part of the AMISOM force tasked with retaking territory from Al Qaeda-allied Al Shabab, and as Somalia is preparing for an election later this year. The militant group released a statement claiming it had recaptured El Adde as soon as the Kenyan troops left.

While AMISOM and Somali forces have forced Al Shabab out of its strongholds, including the capital Mogadishu, the group still launches deadly guerrilla attacks that carry an inescapable message: We are still here.

That message has been reverberating throughout Somalia, which has made significant headway towards recovery after decades of conflict. In November, a United Nations official said that Somalia was no longer a failed state but that the threat posed by Al Shabab remained its greatest challenge.

With Somali politicians divided on how to carry out the election later this year, Kenya’s retreat does not build confidence. That's especially true within Kenya, where doubt over its presence in Somalia has been building.

“This looks like it’s Al Shabab saying ‘We’re here, this is what we can do and we haven’t gone away’,” Cedric Barnes, the Horn of Africa project director for the International Crisis Group told the Financial Times. He added that this month's raid was likely timed to coincide with an election planning conference.

'The mission is still on'

The Kenyan government has described the withdrawal as a relocation that will strengthen Kenya’s presence by allowing its military to set up new bases closer to the border. Military spokesman David Obonyo told local papers that there is little chance of Kenyan troops leaving Somalia all together, reiterating that they are fully committed to AMISOM’s mission in the country.

“After all, there is a reason that took us to Somalia, which is to liberate and pacify those areas, and the mission is still on,” he said. Kenya contributes about 4,000 troops to the 22,000-strong AMISOM force.

Questions over Kenya’s presence in neighboring Somalia peaked after Al Shabab’s deadly attack on Garissa University last year, The Christian Science Monitor's Ariel Zirulnick reported at the time:

The attack on Garissa highlighted Al Shabab’s deadly reach in Kenya, which has deployed peacekeepers to help pacify Somalia. And it revived a national debate over the wisdom of that participation amid a steady uptick in terrorist attacks on Kenyan soil.

[Outside of supporting the AMISOM campaign], Kenya had another goal in Somalia: to make its territory safer after a spate of border incursions by Al Shabab and the kidnappings of aid workers and tourists. Yet this intervention has led to bloody reprisals, from a high-profile attack on a Nairobi mall in 2013 to a slew of killings of Kenyans on buses, in schools, and at mining camps. Critics call it blowback, and blame Kenya’s government for wading into a war it can’t win.

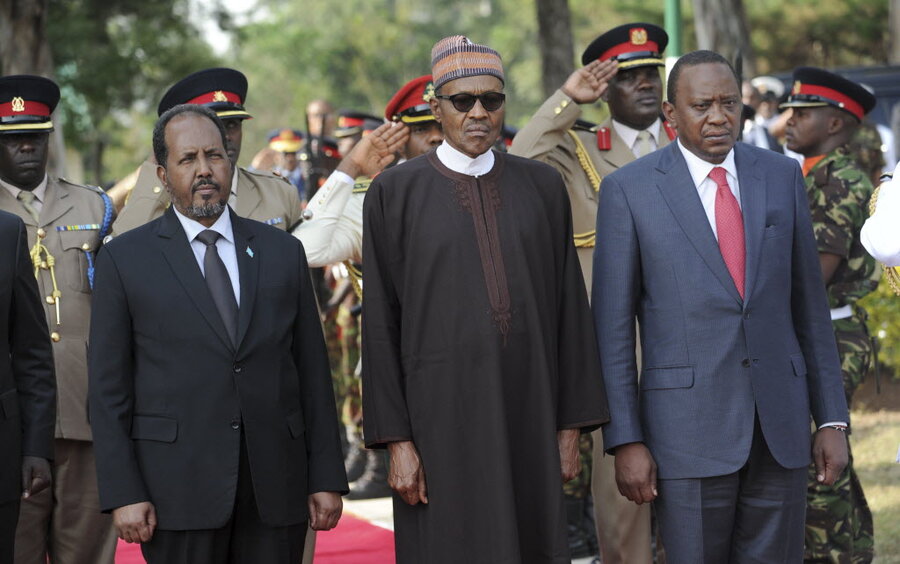

Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta will attend the memorial service Wednesday alongside Somalia's President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud and Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari.

“We will not be cowed by these cowards,” Mr. Kenyatta said in a statement after the Jan. 15 attack. “With our allies, we will continue in Somalia to fulfill our mission. We will hunt down the criminals involved in today’s events. Our soldiers’ blood will not be shed in vain.”