Why can’t the UN stop sexual violence in South Sudan?

Loading...

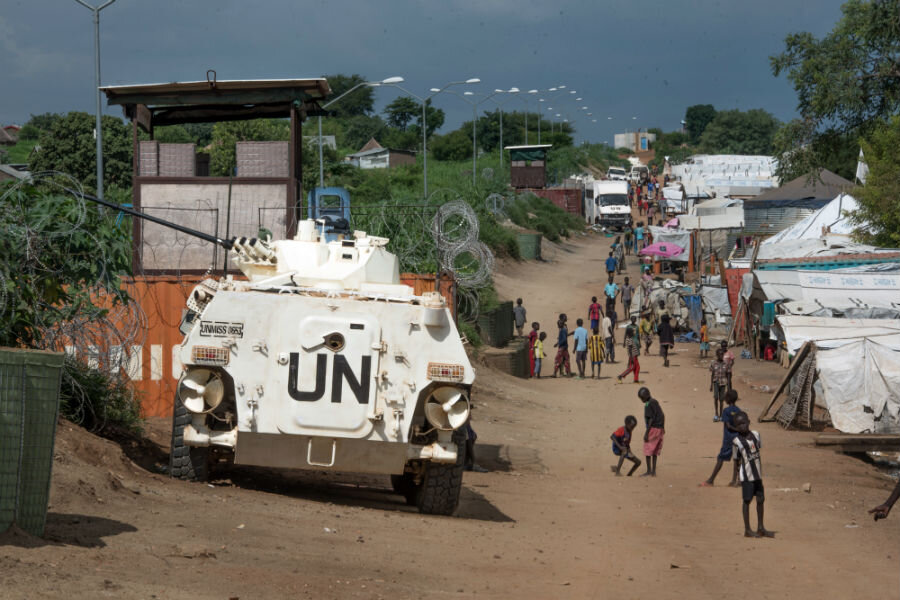

Ethnic hostilities in South Sudan have left the country awash in sexual violence, and some of it may be happening under the nose of United Nations peacekeepers.

The UN said on Wednesday that there had been least 120 cases of sexual violence and rape in the South Sudanese capital of Juba since fighting broke out three weeks ago between forces loyal to President Salva Kiir and those answering to Vice President Riek Machar.

Government soldiers raped dozens of ethnic Nuer women and girls just outside of a UN camp set up to provide shelter for some 30,000 civilians, reported the Associated Press on Wednesday. Two of the victims died from their injuries.

In at least one of the sexual assaults on July 17, armed UN peacekeepers from Nepal and China allegedly witnessed the attack from a guard tower and an armored vehicle.

"They were seeing it. Everyone was seeing it,'' one witness told the AP. "The woman was seriously screaming, quarreling and crying also, but there was no help. She was crying for help.''

Nancy Lindborg, president of the United States Institute for Peace, a federal conflict-analysis group, pointed to a March 2014 decision by the UN to move its emphasis from state building to the protection of civilians.

“I can’t guarantee that these peacekeepers have been fully resourced and trained to carry out that mandate,” she tells The Christian Science Monitor, adding that reports of sexual abuse and other crimes had even come from inside some UN camps, where hundreds of thousands of civilians have sought shelter. “They’re deeply not set up to do what they’re being asked to do in South Sudan right now.”

And the country’s leaders, she noted, are unwilling or unable to rein in forces responsible for abuses.

Government soldiers have blocked the UN from accessing food warehouses, cut off routes to the capital and even looted supplies, causing shortages in the camps, reported The Daily Beast on Thursday. That explains why the women ventured out, according to Angelina Daniel Seeka, regional director of the local human-rights group End the Impunity, who said that the women had gone looking for food.

Ms. Seeka called on military leaders to put a stop to sexual assaults by the rank and file. “We can no longer talk of sexual violence by unknown gunmen. They’re known men who carry out these abuses and walk away without being held accountable,” she said in a statement.

“I want the commanders to direct the military to stop this kind of sexual violence against women.”

On Wednesday, the UN said it was looking into allegations that peacekeepers did not come to the aid of civilians who were sexually assaulted, and pledged “serious repercussions” if allegations were true.

The conflict is effectively the resumption of a war in which rape was widespread. In a five-month span coming in spring and summer 2015, when the war was churning on, the UN recorded more than 1,300 reports of rape in Unity, just one of 10 states in the country.

Alex de Waal, executive director of the World Peace Foundation at Tufts University, said that the sexual violence reflects the military’s “highly irregular” mode of organization.

“It’s not a professional army,” says Dr. de Waal in an interview with the Monitor. “It is a coalition of ethnic militias with each unit loyal to its particular commander.”

“The fighters tend to see their job not as defeating the forces of the other side, but as inflicting punishment and material losses on communities loyal to the other side.”

Frequently, says Ms. Lindborg, soldiers are permitted to commit rapes in lieu of receiving pay. And victims sometimes exchange abuse for their own survival. “It becomes a transactional aspect of survival,” she says.