Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370: Why is it taking so long to find?

Loading...

When Air France Flight 447 from Rio de Janeiro to Paris went down over the Atlantic on June 1, 2009, resulting in 228 deaths, floating debris and a jet fuel slick were found within two days.

It's been three days since Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370 disappeared over the Gulf of Thailand.

Why can't this aircraft be found?

Are there any lessons to be learned from the Air France flight?

In both cases, there was no "mayday" or distress call from pilots. The planes just "disappeared" from the sky.

In the case of AF447, bad weather was a factor. The Air France pilots didn't radio for help because they didn't realize, until it was too late, the severity of their problems. And as some pilots have noted, they don't see a lack of communication as necessarily a sign of a terrorist bomb or the catastrophic failure of the aircraft. As one put it, the priorities are "aviate, navigate, and then communicate."

All reports so far indicate that MH370 encountered no bad weather.

In the case of AF447, good clues quickly emerged as to the aircraft's last location and what might have gone wrong. Brazilian air traffic control had recent contact with the Air France jet and the aircraft had sent a series of electronic messages over a three-minute period from an on-board monitoring system via the Aircraft Communication Addressing and Reporting System (ACARS).

Four days after the crash of AF447, the airline released a transcript of the ACARS data, which indicated that in the last four minutes of the aircraft's flight there were six failure reports and 19 warnings involving navigation, auto-flight, flight controls, and cabin air-conditioning. The ACARS data gave early clues to what went wrong. Ultimately, among the causes of the crash were pilot errors in response to faulty readings from air-speed sensors.

It's not clear whether Malaysia Airways Boeing 777 was equipped with ACARS. Flightglobal reportedly asked Malaysia Airlines about signals from the 777’s ACARS, but the carrier declined to comment citing “pending investigations” by Malaysia’s Department of Civil Aviation.

If authorities had ACARS data telling them what went wrong with the Malaysia Airways flight, that might give them a better idea of where to look.

The last reported position of Flight MH370 – and last radar contact – was over an area of sea between Malaysia and Vietnam. The aircraft disappeared about an hour after taking off from Kuala Lumpur bound for Beijing.

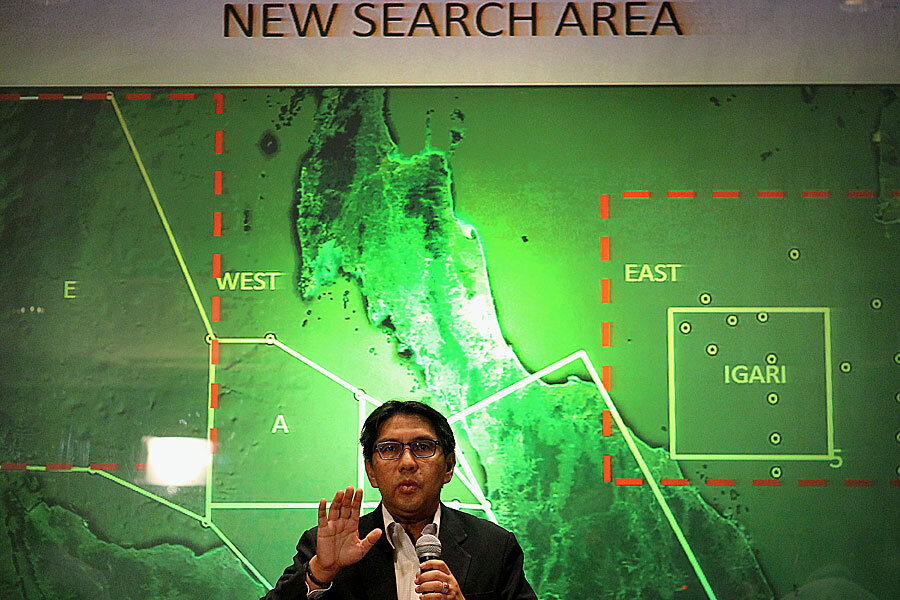

As of late Monday, no debris had been found, and authorities said they were widening the search area. But a map of the widened search area is now raising new questions about how much Malaysian officials know about the missing aircraft's last position.

The search area map now includes not only a wider area around the last publicly reported position of the aircraft, but also a new area in the Strait of Malacca, on the west side of Malaysia peninsula.

That raises new questions about how much authorities know – but aren't telling the public.

Rodzali Daud, the Royal Malaysian Air Force chief, told reporters Sunday that military radar recordings had revealed the possibility that the aircraft had turned back from its scheduled flight path.

That would be highly unusual and under normal circumstances the pilot would have called Malaysia air traffic control to signal a change in the original flight path.

If the aircraft had turned back toward Malaysia, and flown over it, that might explain why the search area now includes both the Gulf of Thailand and the Strait of Malacca. It wouldn't explain why an aircraft would overfly land, and possibly airports, without landing or radioing its position or its transponder giving away its position.

Normally, an aircraft transponder would enable air traffic controllers to locate its position. Assuming, of course, the transponder was still functioning and hadn't been turned off.

This new search zone, and the lack of any debris found in the original search area, has commenters on global aviation sites speculating (in the absence of new facts) that Malaysia Airways Flight 370 was hijacked or taken on a suicide mission by one of its pilots.

"Looking on the other side of the peninsula is just odd, it means they [Malaysia authorities] saw the airplane go over the peninsula on radar, or there are parts of the peninsula that lack radar coverage," writes Web500sjc, who's listed on Airliners.net as a commercial flight instructor in the US.

As another commenter noted, if the engines had died on a Boeing 777 at 35,000 feet, the glide slope would indicate that it could be about 100 miles from the last known location. The Strait of Malacca is more than 250 miles away.

Of course, Malaysian officials may simply be as confounded as everyone else. They certainly sound that way:

“Unfortunately, we have not found anything that appears to be an object from the aircraft, let alone the aircraft … There are many theories that have been said in the media; many experts around the world have contributed their expertise and knowledge about what could happen, what happened … We are puzzled as well,” said Azharuddin Abdul Rahman, Malaysia's civil aviation chief late Monday.