In Ukraine, war speeds migration away from Russian language

Loading...

| Kyiv, Ukraine

Russian had always been Kyiv native Olena Bondarenko’s mother tongue. That all changed with the invasion and accompanying atrocities last year.

“After Bucha, Hostomel, Irpin, and what was discovered, I just can’t speak the Russian language,” she says. “It’s the language of the aggressor and the language of the occupier.”

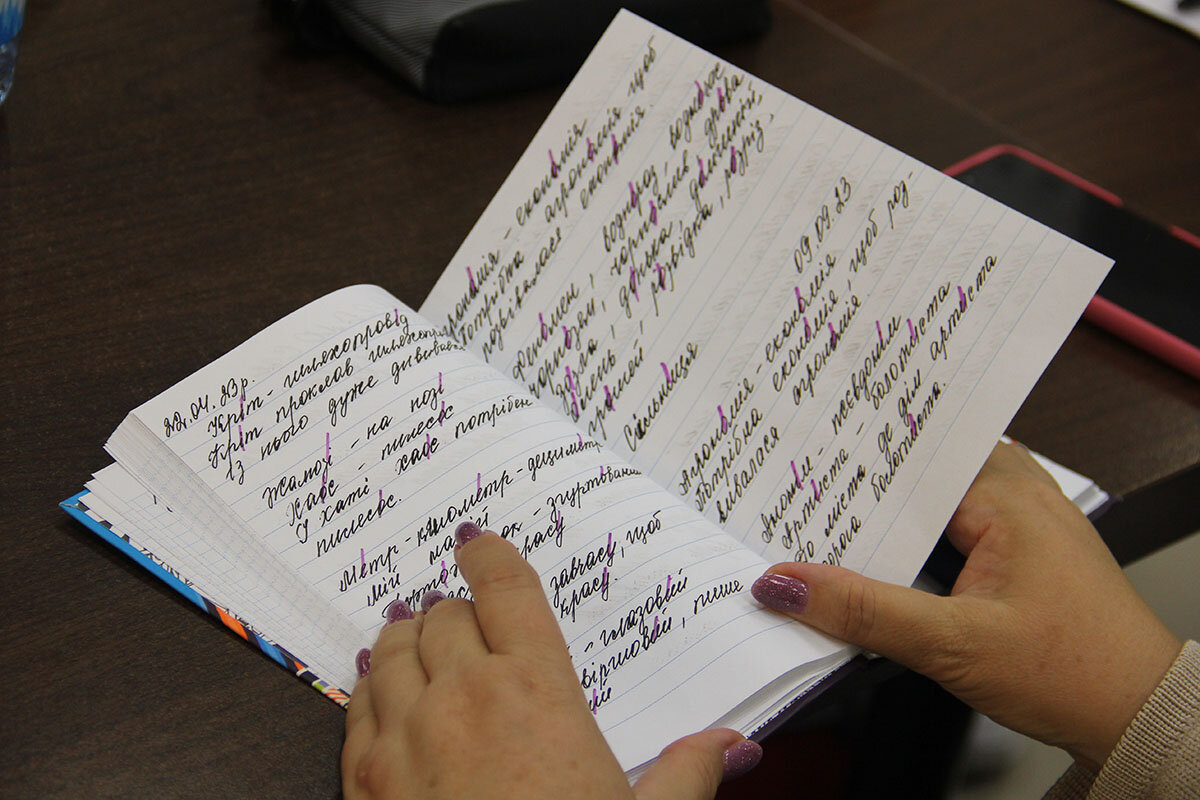

That was what inspired her to come to Anna Pastushok’s weekly Ukrainian conversation group in central Kyiv. But not all the group’s attendees had the same motivation.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onWith the Russian invasion still ongoing, many Ukrainians see the choice between speaking Ukrainian and Russian as more than pragmatic. It is also about patriotism and affirmation of their identity.

“For me, the Ukrainian language is about Ukrainian culture and nurturing it,” says fellow classmate Sasha Voloshchyk. She brought her 5-year-old son, Lev, to the class and showed a home video of them practicing pronunciation emphasis. Originally from the southeastern city of Zaporizhzhia, she switched to speaking Ukrainian in 2017. “When I made the switch, I wasn’t really repelled by Russia. It was simply the attraction of Ukrainian culture and its preservation and respect for my language in my country.”

Whatever their motivation, the students are part of an ongoing movement in Ukraine of people choosing to switch from speaking Russian to their country’s official language: Ukrainian.

In a nation where many people are bilingual, the language people choose to speak is a personal decision and an emotionally charged topic during war. Russian President Vladimir Putin argued his invasion was justified in part by claiming Russian speakers needed to be defended.

But for many Ukrainians, the war with Russia has proven reason to bolster their Ukrainian usage – and for some to abandon usage of Russian entirely. Whether driven by repulsion from Russia or patriotism for their own nation, Ukrainians are changing their lingua franca – and their society.

Language and statehood

Ms. Pastushok’s class, part of a free 28-day online course through the group Yedyni (whose name means “united ones” in Ukrainian), is one example of such efforts to spread the use of Ukrainian. During the conversation group, the students play card games and ask Ms. Pastushok about pronunciation. “People don’t just need knowledge, but also psychological support in the transition because it is difficult,” she says.

Over 102,000 people have already taken Yedyni’s course over the past 19 months, says the group’s co-founder Natalka Fedechko. Perfectionism and embarrassment are the biggest psychological barriers.

Suppression and banning of the Ukrainian language dates back hundreds of years. During Soviet times, Russian was the language used to get ahead in careers, and Ukrainian was perceived as a lesser, village language, Ms. Fedechko says. “This inferiority complex, unfortunately, still exists.”

Ukrainian became the state language in 1989, but at first there was no strict implementation. In 2019, Ukraine adopted a new language law, making Ukrainian the default language in many social domains – not just state offices but private companies, too. Quotas in film, TV, and radio also increased the use of Ukrainian.

The trend “is a gradual shift ... from Russian to Ukrainian,” says Volodymyr Kulyk, a visiting scholar at Stanford University who has been studying language practices and attitudes in Ukraine for the last 20 years. “It was very slow until 2022.”

The latest available data from the end of 2022 shows that across Ukraine, 62.6% of respondents reported speaking Ukrainian at home, 19.2% said they speak both languages, and 15.8% said they spoke Russian. That’s compared with data from 2017, when only 49.9% of Ukrainians reported speaking Ukrainian at home, 23.9% reported speaking both, and 25.8% said they spoke Russian.

It will likely be years before researchers will be able to judge the impact of the war on Ukrainian language usage.

Natalya Pipa, a member of Ukraine’s parliament who works on the Ukrainian language environment of educational institutions, says support for the Ukrainian language is growing, but there is still a long way to go.

While some soldiers on Ukraine’s front lines speak Russian, Ms. Pipa argues that everyone who isn’t serving should have the time to study. “Language and statehood are very much connected,” she says.

“It’s also a cultural war”

Before the invasion, Russian was critical to the livelihood of Anton Ptushkin, who grew up in Luhansk, 45 minutes from the Russian border. Mr. Ptushkin co-hosted a popular Russian-language travel show that was broadcast in several countries before making his own content for almost 5.6 million YouTube subscribers. To be successful meant knowing Russian, and Moscow offered much bigger salaries for entertainers.

For Mr. Ptushkin, everything changed on Feb. 24, 2022. He decided to switch to publishing in Ukrainian, even if that meant losing part of his audience. “It was a no-brainer for me. I don’t have any other choice because for us, it’s also a cultural war,” he says. “This is a historical chance to cut these bonds with Russia.”

Some followers were unhappy and even accused him of being paid to switch. Mr. Ptushkin says it was a “100% conscious decision” not to make any Russian content. He estimates that a little less than half of his current YouTube audience is Russian.

Ukrainian was in Mr. Ptushkin’s subconscious, but learning hasn’t been easy amid the lingering stress of war, which research suggests impacts memory and cognitive skills. He has been reading Ukrainian books and building his vocabulary.

Over a year ago, Mr. Ptushkin and his friend Misha Katsurin decided to film a YouTube show about food across Ukrainian cities and to speak in Ukrainian. He hopes growing Ukrainian YouTube content will help younger Ukrainians develop their skills.

Divergent views

Not all Ukrainians have felt compelled to abandon the Russian language. Some, like Olha Chuyeva, hold on to it in spite of Moscow’s campaign.

Ms. Chuyeva was born in Belarus to two ethnically Russian parents but was raised by Russian-speaking relatives in Yalta, Crimea, following her mother’s death. Ms. Chuyeva says she never felt any attachment to the Russian government, and she moved to Kyiv in 2014 following Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

Sitting in her apartment in central Kyiv where Ukrainian flags hang, Ms. Chuyeva says she has not fully shifted to speaking Ukrainian. “Russia does not own my Russian language. Russia has not usurped the Russian language,” she says, speaking in flawless Ukrainian. “And I don’t want to give it up until I decide I will.”

Russia has taken a lot away already. “The language of the aggressor is theirs. But for me, there is my Russian language that is tied to my own personal history and has nothing to do with Russia,” she says.

Ms. Chuyeva will not speak Russian out of respect to anyone who doesn’t want to hear it, and she argues that Ukrainian should be the state language. But she also says that Ukraine should be a democracy and people should have choice in what they speak. She thinks an approach of “gentle Ukrainization” will be more attractive to people. “You don’t have to force it; you have to wait,” she says. “That can sound cynical; there are people who won’t change. They grew up in the USSR.”

Others are not so willing to accommodate.

Oleksandr Shevchenko, 26, is “super aggressive” about the language question. It’s a big change for the information technology manager who grew up in the eastern Ukrainian city of Kharkiv speaking Russian and Surzhyk, a hybrid mix of Russian and Ukrainian.

On the first day of the full-scale war, Mr. Shevchenko heard explosions soon after waking up. He started writing a social media post in Russian “about how bad the Russians are,” but he stopped when he thought that voicing his complaint in Russian “isn’t right, it shouldn’t be this way.”

Mr. Shevchenko instead wrote his post in Ukrainian, and that was the moment his full change began. He moved to the western city of Lviv and began reading Ukrainian books, listening to Ukrainian music, and eschewing Russian entirely. These days, the only Russian he will speak is to his elderly grandparents, and he thinks that people should feel a responsibility to speak Ukrainian. But Mr. Shevchenko also says he is cynical and thinks if people haven’t already switched to Ukrainian, they won’t.

When asked why he ultimately made the switch he responds with a question: “How else could it be?”