The Berlin Wall fell 35 years ago. Young east Germans fall for relics of the time.

Loading...

| Dresden and Bautzen, Germany

Thirty-five years after millions of East Germans tossed their Soviet-era stuff as quickly as the dump trucks could haul it away, young people who weren’t yet born when communist rule ended are finding joy and identity in certain German Democratic Republic collectibles.

They’re reveling in the pedestrian crossing symbols Ampelmännchen – the plump little traffic-light men – boxy Trabant cars, sleek Simson motorbikes, and the bright-blue clothing of GDR-era youth clubs. An old mustard brand starring in a reel about a sandwich recipe even got 800,000 views on Instagram.

Why We Wrote This

The East-West identity divide did not fall with the Berlin Wall. Young east Germans today take a nostalgic pride in possessing Soviet-era items their parents and grandparents used.

Ostalgie – a combination of the German words for “nostalgia” and “east” – is a gravitation toward symbols of a defunct state and exposes cracks in German unity that were supposed to have disappeared along with the Berlin Wall; it’s also a joyful celebration of an East German identity that young people still connect with.

“I’m not surprised at all. ... They’re pursuing a collective identity that’s different from the West, and also a critique of the way reunification was pursued,” says historian Justinian Jampol, author of “Problematic Things: East German Materials After 1989.” “East German things have gone from being derided to collected to thrown away to exhibited. That ongoing process is a mirror and reflects just how much the history of East Germany is still conflicted.”

For most people, a fork is just a fork.

But when Olivia Schneider spears a stalk of asparagus, she prefers the plastic-handled type dating back to the communist German Democratic Republic (GDR).

It’s the kind of cutlery her East German grandparents eagerly trashed back in 1989 after the fall of the Berlin Wall, 35 years ago this weekend. Finally decades of austerity fell away, and Grandpa and Grandma Schneider set their hearts on filling their house with “really nice West German stuff,” explains Ms. Schneider.

Why We Wrote This

The East-West identity divide did not fall with the Berlin Wall. Young east Germans today take a nostalgic pride in possessing Soviet-era items their parents and grandparents used.

That’s how her grandparents found themselves at one of many impromptu parking lot markets that had popped up, only to be cheated by a West German salesman into paying three times the going rate for cutlery.

“People were just happy they could finally buy things, but they had no idea how much things should cost,” says Ms. Schneider, recounting the tale 35 years later in a café in Dresden, a regional center of the former East Germany.

That silverware scam lives on in three generations of Schneider lore. Ms. Schneider’s brow wrinkles at the story of family indignity as if she’d been personally mistreated. “People just took advantage during the reunification years. It makes me so mad.”

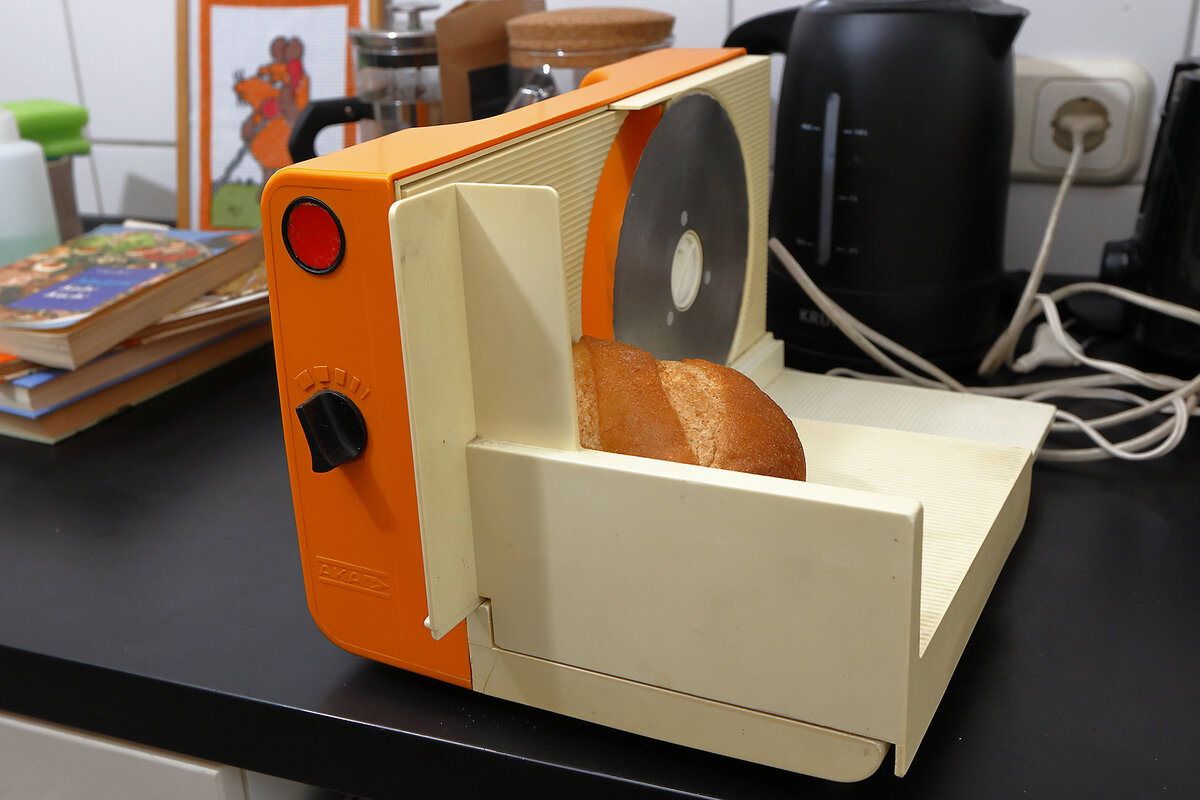

Today, a 28-year-old consumer, Ms. Schneider can buy whatever her budget allows, yet she finds herself choosing the stuff of the now-defunct GDR: that bright-orange bread-slicer, pastel-colored melamine bowls, a stark black veneer dining table.

“I just have this feeling that I want to bring back things that were seen as negative. It’s empowerment to revive them in a better context,” says Ms. Schneider, a social worker and influencer around all things East German with a 30,000-strong Instagram following.

The Berlin Wall fell and landfills swelled with Soviet junk

Thirty-five years after millions of East Germans tossed their Soviet-era stuff as quickly as dump trucks could haul it, young people who were not born when communist rule ended are finding joy in certain GDR collectibles.

They’re reveling in the pedestrian crossing symbols Ampelmännchen – the plump little traffic-light men – boxy Trabant cars, sleek Simson motorbikes, and the bright-blue clothing of GDR-era youth clubs. This gravitation toward symbols of a defunct state exposes cracks in German unity that were supposed to have disappeared along with the Berlin Wall; it’s also a celebration of an East German identity that young people connect with.

“I’m not surprised at all that young people are consuming and presenting East German things. They’re pursuing a collective identity that’s different from the West, and also a critique of the way reunification was pursued,” says historian Justinian Jampol, author of “Problematic Things: East German Materials After 1989.”

“East German things have gone from being derided to collected to thrown away to exhibited. That ongoing process is a mirror and reflects just how much the history of East Germany is still conflicted,” Dr. Jampol adds.

East German goods were built to last

German youth might not use the word Ostalgie – constructed from the German words for “east” and “nostalgia” – yet many hesitate to discard an East German identity the West tried to crush during reunification, says Dr. Jampol.

Their devotion to East German things is exuberant, but also respectful of clean design and construction that was “built to last,” says Benno Auras, 35, a social worker born in 1989.

“East Germany was a country where there was nothing or very little – obviously it was about making products that wouldn’t break the day after tomorrow,” says Mr. Auras. He still tinkers with his Simson using “50-year-old GDR power tools that still work,” he says. “Respect. Nowadays you see only junk which costs a fortune.”

People who collect GDR artifacts certainly aren’t longing for the wall, the Stasi secret police, or the communist regime, explains Katja Hoyer, a historian and author raised in east Germany. “More than that, there’s a personal history, and a family history that’s connected to these items. It’s your cultural product, something that gives you identity and roots especially in times of uncertainty.”

A persistent economic divide certainly feeds Ostalgie, as well as a sense, for some, that “The past has been better, or should be revived in some ways,” says Johannes Kieß, a political sociologist at the University of Leipzig.

East Germans still lag behind west Germans in disposable income and inherit only half as much wealth. Nearly two-thirds of east Germans say they still feel like second-class citizens.

East German, and proud of it

Back in Dresden, Ms. Schneider sips a cappuccino as she recounts her parents’ post-Berlin Wall life paths. Her mother became a chef’s apprentice, and her father landed a job as a Wrigley chewing gum salesman.

They had jobs, yet on a student trip to Hamburg, Ms. Schneider still noticed a gap. Her west German peers got monthly allowances, their mothers didn’t work, and they could travel abroad on a moment’s notice with family funds.

“I was a bit jealous that they had rich parents,” says Ms. Schneider. “No one funded my lifestyle. I always had side jobs, working at the Christmas market, or as a barista or nurse.”

Soon after, she began reading what she dubs the “East German bible” for youth, “Ostbewusstsein.” The full title translates to “Eastern Consciousness: Why Postreunification Children Fight for the East and What This Means for German Unity.”

Today, Ms. Schneider is a social worker and an Instagram influencer whose buoyant missives about East German identity have a defiant undertone. One post about the East German mustard Bautz’ner Senf clocked 800,000 views, and she has attracted brand sponsorships from companies such as Filinchen, the “original GDR crispbread.”

Her parents find it ironic that she is celebrating stuff from the GDR scrap heap; in 1990, East Germans tossed out an average of 1.2 tons of material per person.

“It’s a pity. My parents always told me they threw everything out because they just couldn’t bear to see it anymore in their house,” says Ms. Schneider.

“They had this dream of a unified Germany.”

Editor’s note: This article, originally published Nov. 8, was updated to correct the spelling of the German word Ampelmännchen.