Holocaust papers released: When 'following orders' doesn't cut it

Loading...

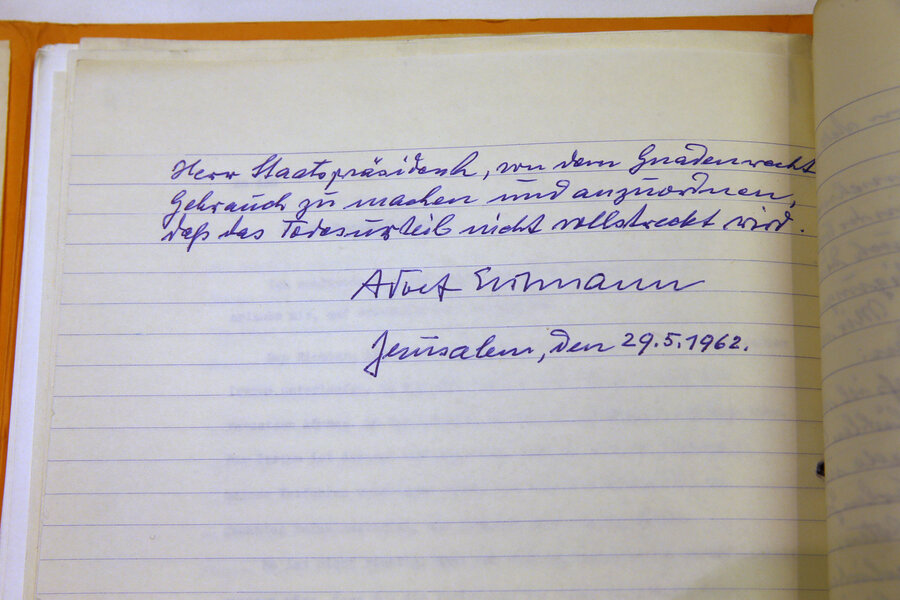

A Nazi war criminal convicted by Israeli courts in 1961 made a final plea for clemency – seen in a note released by Israel's president Wednesday – as he repeated without success an oft-made claim that he had "acted on orders."

The last-minute plea for clemency by Adolf Eichmann two days before his execution on May 31, 1962, was well known, but the release of the note on International Holocaust Remembrance Day shows the futility of bureaucratic pressure as an excuse for committing atrocities, the BBC reported.

"I never gave any order in my own name, but rather always acted ‘on orders,’” Eichmann's note reads. "In their evaluation of my personality, the judges have made a significant error, since they cannot put themselves in the time and situation I was in during the war years."

While some low-level Nazis may have convinced judges that atrocities were above their pay grade, in light of what historians now know about Eichmann, his claim of innocence appears “absolutely absurd given his particular role,” Laurel Leff, a professor at Northeastern University who has researched the Holocaust response, told The Christian Science Monitor in a phone interview.

The world has ignored such excuses in what is both a testimony to the need for individual courage and the reality that some Europeans resisted persecuting Jews at great personal cost. Despite stories about sympathetic Christians who operated underground rescue efforts, historians have also found that many ordinary Germans who could have been excused from participating in massacres chose to continue. In describing a German battalion ordered in 1942 to exterminate a village of Polish Jews, the BBC wrote:

"[Major Wilhelm] Trapp said that those who did not want to take part, could step aside. Of the 500 men standing there that day only fifteen chose to opt out of the killing. The rest went on to massacre all the Jewish women, children and elderly people in the village."

Israeli President Reuven Rivlin released the note, along with similar notes from Eichmann's wife and brothers, on Wednesday with a statement justifying Eichmann's execution.

"Not a moment of kindness was given to those who suffered Eichmann's evil – for them this evil was never banal, it was painful, it was palpable," he said in a statement, according to the BBC. "He murdered whole families and desecrated a nation. Evil had a face, a voice. And the judgement against this evil was just."

Eichmann was captured by Israeli intelligence in 1960 in Argentina, where he had fled. The Israeli government decided to try him and even paid for his defense attorney to demonstrate its commitment to justice and raise awareness of the Holocaust.

The Eichmann trial highlighted the distinctly Jewish suffering of the Holocaust, which had otherwise become somewhat lost in the history of a war that killed millions of civilians, Ms. Leff says. Even the Nuremburg Trials had involved very few witnesses, so the Eichmann trial, featuring testimony by Holocaust survivors, was "absolutely pivotal," she says.

The Eichmann trial was a months-long news event and watershed moment even in Israeli society, where the Holocaust had been overlooked due to both concern with current Israeli affairs and a desire to emphasize Jewish strength over victimization.

Eichmann refused to admit his own guilt and claimed he had asked to be transferred to another post during the war rather than be "forced to serve as a mere instrument in the hands of the leaders." He said he cooperated during his interrogation by Israeli police so the real "perpetrators of these horrors" could be punished, Ofer Aderet reported for the Israeli newspaper Haaretz. His defense attorney's clemency plea blamed politics for Eichmann's actions.

"Eichmann’s actions were caused by political events that occurred more than 17 years ago," defense attorney Robert Servatius, a German, wrote at the time. "He, an unimportant figure, was driven into it by fate … an individual cannot be held accountable for the complexity of events, for the horrors of which the entire German people have been compelled to atone, with large sacrifice and suffering."

The plea of acting strictly under orders was made during the Nuremberg Trials in 1945 with similar results. The prosecutors were determined to hold a fair trial, but they also believed that the bureaucratic nature of their crimes did not absolve Nazi officials. The 1945 statement by Pastor Martin Niemöller has come to symbolize the need for personal responsibility, even before overwhelming pressure:

In Germany they came first for the Communists, and I didn't speak up because I wasn't a Communist. Then they came for the Jews, and I didn't speak up because I wasn't a Jew. Then they came for the trade unionists, and I didn't speak up because I wasn't a trade unionist. Then they came for the Catholics, and I didn't speak up because I was a Protestant. Then they came for me, and by that time no one was left to speak up.