What archaeology tells us about the Bible

Loading...

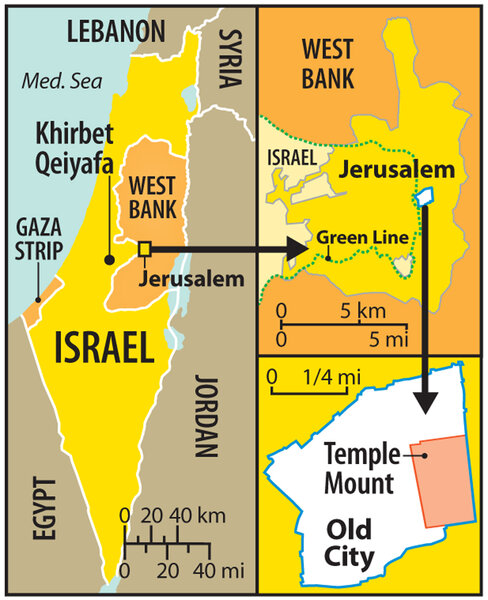

| Khirbet qeiyafa, Israel

The workday is just beginning in Jerusalem, 20 miles to the northeast over folded ridges and misty valleys, but the sound of clinking trowels and creaking wheelbarrows has been echoing across this hillside since dawn. Dust billows up in the morning sun as a worker sweeps away a section of the excavation, where Hebrew mingles with American accents and yarmulkes with wide-brimmed hats.

Clad in soggy T-shirts, the crew sifts through the ruins of a city that some archaeologists believe was part of the biblical realm of King David 3,000 years ago. At 8:30 a.m., Yosef Garfinkel, the codirector of the dig, arrives to survey the project, one of the most prominent and politically sensitive in a country rife with historical excavations.

He grabs diagrams and maps from a trailer and barely settles in under a canopy when a coin specialist, Yoav Farhi, approaches him expectantly. Mr. Farhi extracts a tiny white envelope from his pocket and, with dirt-encrusted fingers, pries open the stiff paper to reveal the treasure inside – a coin from the era of Alexander the Great, imprinted with the visage of the Greek goddess Athena.

"This is the dollar of the ancient world," Farhi tells a visitor. "Mid-4th century BC."

(Editor's note: The original version misstated the date of the coin.)

Mr. Garfinkel, a professor at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, examines the coin, the size of a thick quarter. He smiles. Each discovery delights Garfinkel, but it is more than ancient currency that has drawn the world's attention to this serene hilltop overlooking Israel's Valley of Elah, where David felled Goliath with a sling.

Instead, it is what Khirbet Qeiyafa has revealed about David's reign, about the emergence of ancient Israel, and, by extension, about the historical accuracy of the Bible itself.

For the past 20 years, a battle has been waged with spades and scientific tracts over just how mighty David and the Israelites were. A string of archaeologists and Bible scholars, building on critical scholarship from the 1970s and '80s, has argued that David and his son Solomon were the product of a literary tradition that at best exaggerated their rule and perhaps fabricated their existence altogether.

For some, the finds at Qeiyafa have tilted the evidence against such skeptical views of the Bible. Garfinkel says his work here bolsters the argument for a regional government at the time of David – with fortified cities, central taxation, international trade, and distinct religious traditions in the Judean hills. He says it refutes the portrayal by other scholars of an agrarian society in which David was nothing more than a "Bedouin sheikh in a tent."

"Before us, there was no evidence of a kingdom of Judah in the 10th century [BC]," says Garfinkel. "And we have changed the picture."

But critics question his methods on the ground and his interpretations in scholarly journals.

The dispute transcends the simple meaning of ancient inscriptions found at Qeiyafa, or the accuracy of carbon-dating tests on olive pits. It highlights the whole dynamic between archaeology and the Bible – whether science can, in fact, help authenticate the Scriptures.

"If you are in the trenches of what's going on today, the battle for Qeiyafa looks very important," says Israel Finkelstein, an archaeologist at Tel Aviv University and one of Garfinkel's most prominent critics. "But if you are zooming out, you see that all this is another phase in a very long battle for the question of the historicity of the biblical text, for understanding the nature of the Bible, for understanding the cultural meaning of the Bible."

The dispute is exacerbated by the imprecision of archaeology, a discipline that is as much art as science. What ancient potsherds reveal about the past is subject to interpretation, which is shaped by prevailing cultural views, history, religion, and politics. And perhaps nowhere in the world is the nexus of religion and politics more combustible than in the Middle East.

Indeed, in a land where the theme of building a nation in the face of hostile neighbors is every much a part of the modern narrative as the biblical one, the debate over Qeiyafa and other digs around Israel reverberates well beyond the field of archaeology.

With each flick of a shovel, with each discovery of an ancient gate, with each sensational TV documentary, new claims and counterclaims are made that inflame modern politics and raise an age-old question: Can science ultimately prove – or disprove – the Word that the Psalmist wrote is forever "settled in heaven?"

• • •

Israel Finkelstein's life arc shares a certain symmetry with that of Israel: He was born in 1949, one year after the founding of the country and the same year an armistice ended Israel's war of independence with its Arab adversaries.

The young Finkelstein grew up just east of Tel Aviv, and by age 13 he had acquired such a curiosity about archaeology that one weekend he and his friends rode their bikes out to the site of Tel Afek, an excavation close to the Jordanian-held lines. His risky expedition drew such a stern reprimand from his father, he wrote years later, that it made him regret for a time his interest in history.

But as both Israels came of age, the adolescent state won the 1967 war with its Arab neighbors in less than a week, in effect pushing the boundary of exploration to the Jordan River. That opened the way for a new generation of Israeli archaeologists to dig into the history of ancient Israel for the first time.

Suddenly, the sojourns of Abraham, the kingdom of Saul, the escapades of David – all were encapsulated in a theater of history that their descendants rushed in to explore. Many hoped to find archaeological evidence that would support the biblical narrative, and solidify the modern state's claims to the land.

True, the Zionist movement that spearheaded Israel's establishment was largely secular. But it also drew heavily on the Bible. Founding father David Ben-Gurion pushed aside the image of bespectacled Jews poring over rabbinical teachings and championed instead the brawny heroes of the Bible, who overcame insurmountable odds to conquer Israel's enemies. These included David and Solomon, who, according to the Bible, joined the tribes of Israel and Judah into a kingdom known as the United Monarchy.

"For Ben-Gurion, the image of a great United Monarchy with territorial expansion ... establishing a nation, establishing a big administration with monumental architecture – this was an image that played back and forth, between that David and this David, between King David and David Ben-Gurion, in a way," says Finkelstein.

Finkelstein himself chose early on to dig at Shiloh, the ancient capital of Israel for more than 300 years before the Hebrew people built a temple in Jerusalem and enshrined it as the heart of their nation and religion. But as he spent the next 20 years exploring the mountainous lands of the West Bank with modern archaeological tools and methods, he began questioning the accepted practices and conclusions of earlier years that had been used to validate biblical stories.

Two of the most prominent proponents of these theories were William Albright, a devout son of American missionaries, and Yigael Yadin, a former Israeli military chief of staff who became one of the country's most lionized archaeologists. Albright sought to illumine the Bible with his finds in the Holy Land, while Yadin shored up Israel's nationalist narrative with what he believed was irrefutable proof of the mighty kingdom that prospered under David's son Solomon. In Megiddo, Hazor, and Gezer, a trio of cities mentioned by the Bible as Solomon's chief building sites apart from Jerusalem, Yadin uncovered monumental gates whose similar styles indicated a common architect. He also found two palaces at Megiddo, which he dated to the same era.

But after the 1967 war, criticism began building of the validity of both biblical and archaeological explanations of ancient Israel. In the 1990s, historians and biblical scholars – concentrated mainly in Copenhagen, Denmark, and Sheffield, England – launched a frontal attack on the Bible as a legitimate historical source. This coincided with Finkelstein's growing conviction that his field had long espoused biblical narratives too indiscriminately, particularly in regard to the era of David and Solomon.

In 1996, he upended the United Monarchy theory with an article in Levant, a British scholarly journal, which argued that the dating method that had been used so far, known as "high chronology," was off by close to a century.

"The biggest question is who and what was Solomon – just a little tribal leader, or a king who had a kingdom and built enormous structures?" says Hershel Shanks, founder and editor of Biblical Archaeology Review, who has challenged Finkelstein's conclusions. Assigning key discoveries to a later period undermined the most compelling proof that Solomon was a notable potentate, since he would have lived before the time of the gates unearthed at Megiddo, Hazor, and Gezer. The result is that "you no longer have any evidence of Solomon," says Mr. Shanks. "What you thought was a kingdom of considerable importance has now disappeared."

But in the nearly two decades since Finkelstein introduced his "low chronology" theory (lowering the start of the period from 1000 BC to 920 BC), research has narrowed the gap between the two schools to 30 to 40 years. Thus supporters of the more traditional timeline feel reinforced by the findings being uncovered at Qeiyafa. "I think the tide is against Finkelstein's low chronology," says Shanks.

• • •

In Israel, nothing from the United Monarchy period has yet been found that is as grand and definitive as the towering pyramids of Egypt, or the nearly intact tomb of King Tutankhamen, with its golden burial mask and sarcophagus. And apart from the Bible, there is only one mention of Israel prior to the 9th century BC – the Merneptah Stele, an inscription from about 1205 BC, which was unearthed in Egypt.

That has given rise to difficult questions. If Israel was such a mighty kingdom under David and Solomon, why didn't other regional leaders mention them? And why was the archaeological footprint of Jerusalem, its capital, so small?

Spades alone haven't been able to answer the questions. "Archaeology is mute," says Amihai Mazar, professor emeritus of archaeology and biblical history at Hebrew University.

But archaeologists are not. To a certain extent, they are storytellers, who fill in the gaps with interpretation. Many are trained in additional fields, such as history, ancient languages, or religious studies, that allow them to explore and hypothesize well beyond the bounds of artifacts and methodical measurements.

That's especially true of the early United Monarchy period, before there were coins or seals with people's names on them that could be used to verify dates, says Eric Meyers, a religion professor and biblical archaeologist at Duke University in Durham, N.C. "There is always an interpretive jump that is made by individuals, and you have to be wary of who's doing it and what they're doing with it."

To be sure, archaeologists working in Israel have developed sophisticated techniques for piecing together ancient history, such as dating certain layers based on pottery shards or on events such as a catastrophic fire.

Picking apart the layers and cataloging the finds is a painstaking process – and carries a note of finality. Once the wheelbarrows of dusty brushes and trowels, the tent stakes and faded canopies have been carted away, and the boxes of discoveries carefully cataloged, there is little recourse if other archaeologists or experts question the findings.

"In experimental science, usually there is a way to rehearse the experiment, to redo it, to rerun it," says Finkelstein. "In archaeology there is no rerun because we destroy our own experiment."

One improvement in recent decades is more-precise carbon dating, which calculates the age of organic matter based on the extent of radioactive decay. But the accuracy of such techniques is still only good to within about 30 years – similar to the gap that remains between Finkelstein's low chronology and the more conservative high chronology.

"The debate around radiocarbon dating, after we invested a lot of money and effort in [it], is whether ... it is refined enough to really resolve such a problem," says Dr. Mazar of Hebrew University, who is widely respected by archaeologists on both sides of the debate. "And that's a big question."

So even after all the painstaking spade work, after all the precise measurements and GPS calibrations, archaeologists are left with only a partial narrative. How they fill in the rest of the story about people who trod the ground here 3,000 years ago is where the interpretation – and controversy – comes in.

"Good scholars, honest scholars, will continue to differ about the interpretations of archaeological remains simply because archaeology is not a science, it is an art," William Dever, a biblical archaeologist, once wrote. "And sometimes it is not even a very good art."

• • •

The dig at Qeiyafa is not likely to be mistaken for an "Indiana Jones" movie. There's no one strutting around with swagger and derring-do. No one is carrying a curled-up bullwhip on the hip, though codirector Saar Ganor does have a pistol tucked in his pants. Instead, the scientists and volunteers from Israel and the United States, trowels, brushes, and shovels in hand, toil patiently among the ancient walls on the last days of an excavation that began in 2007.

And then there's Garfinkel, passionate but unassuming, moving among the ruins in his red baseball cap. The avuncular archaeologist is more accustomed to obscurity than the spotlight. He once worked on a prehistoric dig in the Golan Heights that yielded hundreds of figurines, some of which ended up in the Louvre in Paris and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. But "nobody cared," he says.

Qeiyafa is different, however. It taps into the legacies of one of the most revered historical figures in the Israeli mind, King David.

On a vista overlooking the Valley of Elah, Garfinkel points out the fortress walls of the ancient city in which residences abutted the outer city wall. Judean civilization, perhaps foreshadowing kibbutz life, was tightknit, he says. Then he scrambles farther down the hill to a wide gate – one of two in the city wall.

The presence of a second gate, an unusual feature for a city of that time, has led him to conclude that this is Shaaraim ("two gates" in Hebrew), which is mentioned in the Bible's description of the aftermath of David's battle with Goliath.

He knows well the criticisms of his conclusions. But he remains unmoved by them. As he sits down on the stony ledge where the gate once stood, he says he is satisfied, after seven seasons of excavation, with the portrait he has sketched of Qeiyafa in the 10th century BC – of a small, fortified city that stood on a regional border between the Judean kingdom and larger Philistine cities.

In addition to the urban planning reminiscent of Judean civilization, his team found a 70-glyph inscription containing Hebrew words such as judge and king. The ruins of what he believes was the governor's palace in the middle of the city, together with a large storeroom, point to a social hierarchy indicative of regional politics rather than a loose confederation of tribes or independent shepherds. Remains of pottery jars with matching indentations suggest to him a primitive form of central taxation, in which the jars would be distributed to citizens, who would then return them full of agricultural produce.

Clues also come from what was not found. In Canaanite cities of the time, pig bones have accounted for 2 to 3 percent of all animal bones discovered, while in Philistine cities, such as Gath, it was as high as 15 to 20 percent, he says. In Qeiyafa, not a single pig bone has been found among the thousands of skeletal remains excavated, suggesting a custom of not eating pork.

Likewise, Garfinkel's team didn't find any cultic figurines in more than 60 rooms. "We don't have any naked ladies," he says, drawing a contrast with Canaanite or Philistine cultural practices. But he did find a model of a shrine reflecting a new type of architecture, which he says closely matches detailed technical descriptions of Solomon's temple in the Bible.

While all this may sound convincing to the average person, it doesn't to Finkelstein. In 2012, he and a colleague from Tel Aviv University, Alexander Fantalkin, wrote an article that rebutted Garfinkel's assertions point by point. It concluded with a scathing commentary on the "sensational way in which the finds of Khirbet Qeiyafa have been communicated to both the scholarly community and the public."

"Khirbet Qeiyafa is the latest case in this genre of craving a cataclysmic defeat of critical modern scholarship by a miraculous archaeological discovery," they wrote.

Yet Mazar, perhaps Finkelstein's most articulate debating partner over the past 15 years, has written a critique of the critics. He has argued that "one cannot avoid asking whether scholars who are trying to deconstruct the traditional 'conservative bias' are not biased themselves by their own historical concepts. In other words, it seems to me that the same charges used against conservative traditional biblical archaeologists can be made against a broad spectrum of minimalists, revisionists, post-modernists, or whatever term we use for a variety of current writers."

Still, despite all the controversy surrounding the dig, many experts see the work at Qeiyafa and other sites around the country yielding something vital – bringing the Bible to life.

"In my own mind, it's helped me say, 'Geez, these things are not coming out of thin air,' " says Jonathan Waybright, a professor of religious studies and archaeology at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, who has worked on digs in Israel for 25 years, most recently at Qeiyafa. "It's adding substance to the biblical story."