Kurdish crisis: As masses seek refuge in Turkey, fighters rush back to Syria

Loading...

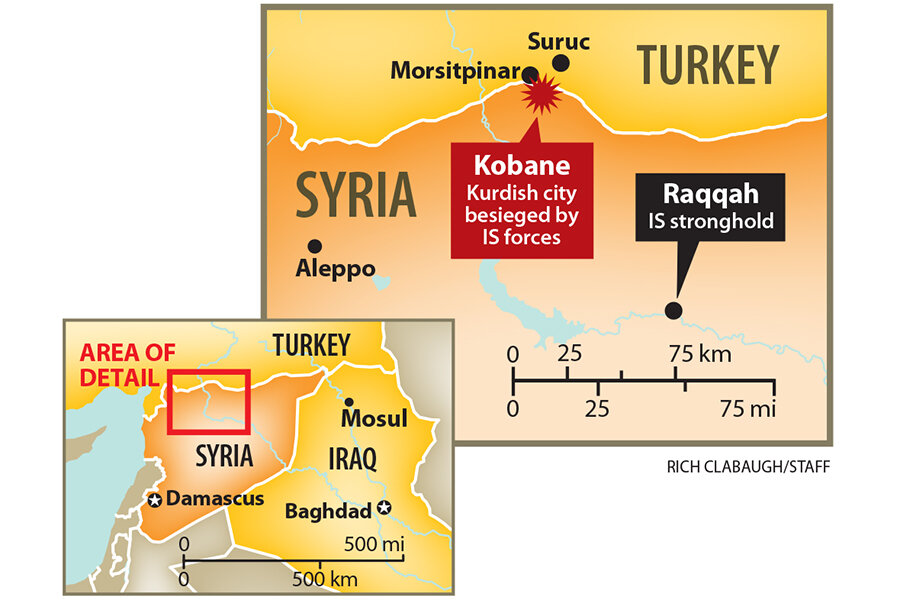

| Mursitpinar, Turkey

Hundreds of Kurdish men streamed into Syria from Turkey Monday, saying they hoped to defend a strategic border town from an onslaught by Islamic State, a jihadist group bent on expanding its so-called “caliphate” in Syria and Iraq.

The clamor to enter Syria marked a dramatic reversal in the cross-border traffic after several days in which Syrians, most of them Kurds, fled the IS advance in Syria, seeking refuge in Kurdish areas of Turkey. Officials Monday put the number of Syrian refugees to cross into Turkey over the weekend at 130,000.

“I’ve been waiting for two days to enter” Syria, says Mahmoud Ahmed, a 19-year-old Syrian Kurd from the besieged town of Kobane, also known as Ayn Arab. He was one of hundreds of men, young and old, to line up to cross Monday. “Yesterday we pelted Turkish soldiers to pressure them to let us in. Today they opened the gate,” he explains.

Fit Kurdish men jogged to the border gate of Mursitpinar eager to join the wave crossing into Syria. “The Islamic State will not set foot in Kobane as long as we are alive,” vows Mohammed Mohammed, a native of the town, who says he flew from Morocco to Turkey to join the fight.

“We ask the Turkish government not to close the border and not to be complicit in the crimes of the Islamic State. Every Kurdish man from age 7 to 70 is willing to take up arms. We are all with our brothers of the YPG,” he adds.

The Syrian Kurdish YPG, or People’s Defense Units, had carved out a semi-autonomous region in northeast Syria. It is a sister faction of the PKK, or Kurdish Workers Party, which has bases in northern Iraq and is branded a terrorist organization by Turkey, the European Union, and the United States. In the fight against Islamic State, ethnic Kurdish solidarity visibly transcends borders and creates diplomatic pickles.

Kobane surrounded

“A lot of young people reached the center of Kobane today to fight alongside the YPG. There are fierce clashes against the Islamic State,” says Anwar Moslem, a Kurdish defense official reached by phone in Kobane. IS fighters have the town surrounded from the east, west and south. Its forces have overrun dozens of villages in the area and are just five miles from the heart of the town.

Lightly armed, the PKK and YPG have established themselves as forces to be reckoned with in both Syria and Iraq, much to the chagrin of Turkey's government, which has opposed Kurdish autonomy. On paper, peace talks are underway between the PKK and the Turkish government, which fought a war that claimed 40,000 lives since 1984. Turkey is now under pressure from the US and other Western powers to join their anti-IS coalition.

Monday afternoon, border area tensions spilled over near the town of Suruc. Police resorted to tear gas and water cannon to disperse Kurds who arrived from all corners of Turkey to defend their kin in Syria. Some demanded to cross over while others denounced Turkey for not doing enough to stymie IS and to help Kurds.

Kurdish protesters charge that Ankara sponsors and arms IS, facilitates the flow of fighters and weapons into Syria, and provides medical treatment for its wounded. Those charges have echoed to a degree in Turkey in parliament and some media; Turkey's government denies the charges.

The linchpin of the suspicions here is the confluence of recent events. On Saturday, Turkey announced that it had secured the release of 49 Turkish hostages held by IS in Iraq since June. At the same time, Kurds were fleeing the Kobane onslaught by IS fighters.

“They (the government) don’t want to support Kurdish fighters on the other side of the border because in their hearts they are with IS,” charges Nazmi Yasser, a Turkish Kurd fleeing a stinging cloud of tear gas.

Soaked from head to toe after getting caught up in the clashes with police, Mahmoud Hassan, a native of Kobane, says he has a simple appeal to the Turkish authorities: “We ask our Turkish brothers to facilitate the passage of civilians because women and children are paying the highest price.”

Mosques for shelter

Meanwhile, the UN refugee agency announced Monday it is stepping up its response to help the Turkish government provide assistance to an estimated 130,000 Syrians who have crossed into Turkey since Friday.

Residents of Suruc and other Kurdish villages dotting the border have taken in a large portion of the refugees. Those without relatives or acquaintances in the area have turned to mosques for shelter, where good Samaritans brought boxes of food and gallons of water. Armored vehicles patrolled the streets.

Anticipating a protracted crisis, some refugees have already set about finding work. One Syrian Kurdish family busily picked the cotton fields of their hosts. A little girl, Samira, sat nearby clasping a jar of earth she scooped up from Kobane. “She didn’t want to forget the smell of her land,” explains her mother, Wardi Ahmed, fighting back tears.

Ms. Ahmed, a lawyer still dressed like she was heading to the office, says she regrets leaving her children’s schoolbooks behind. “All we could do was flee in time to protect our children from slaughter. But what will we do? In Turkey you can’t make enough money to support a family, the same goes for Iraq, and Syria is at war.”