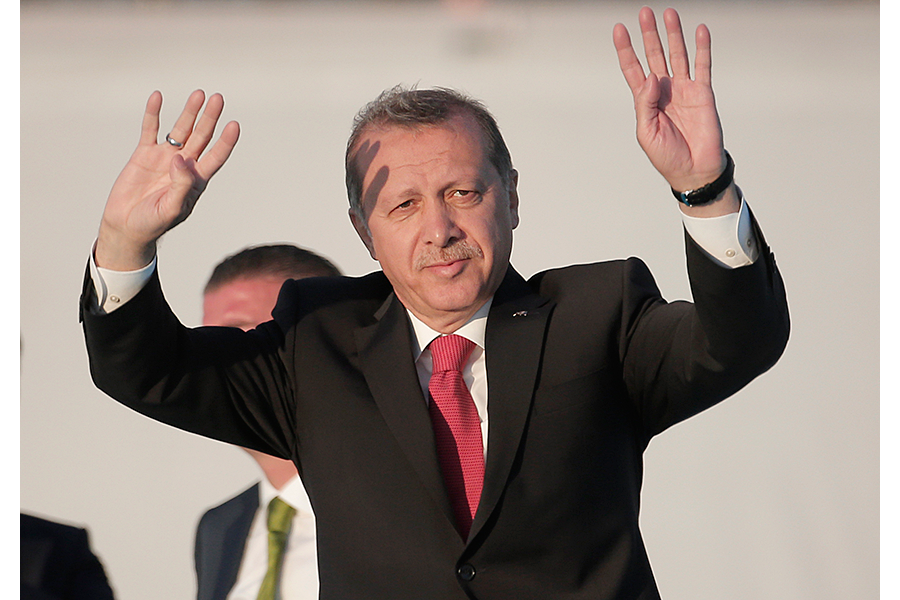

Turkey's Erdogan appears to be back in control, taking aim at new elections

Loading...

| Ankara, Turkey

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan appeared a shadow of his former self after his party suffered major losses in June elections – embattled and no longer in control of his political fate. His once-dominant movement was forced into the humiliating position of seeking a coalition with opposition parties intent on reining him in.

Two months on, the shrewd politician seems to be back in the saddle. The coalition-building he reportedly opposed has collapsed, and Turkey is now edging closer toward the repeat elections that he has been angling for.

Erdogan appears to be betting that a new ballot could revive the fortunes of the Islamic-rooted party, which he founded and led for more than a decade. That would put him back on course to reshape Turkey's democracy, giving the largely ceremonial presidency sweeping powers that would allow it wield control over government affairs.

Last week, he claimed that since he was elected by popular vote instead of by Parliament, Turkey now had a "de facto" new system with a more powerful president, and a new constitution was needed to reflect the change. Erdogan has already been overstepping the bounds of his symbolic role, and is believed to be calling the shots on most matters of state, including Turkey's fight against terror.

But new elections at a time of escalating violence between Turkey's security forces and Kurdish rebels – and amid Turkey's deeper involvement in the U.S.-led campaign against Islamic State extremists – could backfire.

In recent weeks, dozens have been killed in renewed clashes between Turkey's military and the rebels of the Kurdistan Workers' Party, or PKK. Turkish jets have conducted air raids on IS targets in Syria and Kurdish rebel positions in northern Iraq, while U.S. jets last week launched their first airstrikes against IS targets in Syria from the key Turkish base at Incirlik, close to the border with Syria. The truth is Erdogan is already calling the shots, including on military affairs, behind the scenes.

"Erdogan is back in the driver's seat," said Svante Cornell, Director of the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute. "But the car's wheels are falling — and the car is breaking down."

The ruling Justice and Development Party, or AKP, came first in the June 7 elections, but fell short of a majority for the first time since it came to power in 2002. A coalition government would have limited Erdogan's ability to steer the government from behind the scenes.

After weeks of stalling, Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu, a former foreign minister and Erdogan adviser, embarked on talks with Turkey's pro-secular party leader, Kemal Kilicdarogu, to seek a common ground for possible with coalition. The power-sharing talks failed on Thursday, days after Kilicdaroglu accused Erdogan of obstructing the coalition efforts – a view shared by many. Erdogan denied he stood in the way of the coalition efforts.

Davutoglu held a failed last-ditch coalition meeting with the leader of Turkey's nationalist party just days before the Aug. 23 deadline for the formation of a government runs out – leaving Turkey with little option but to hold new elections, probably in November.

Erdogan is apparently betting that this time around the party could reverse its losses, with many voters who deserted the party returning to avoid the prospect of another uncertain coalition.

Opponents have accused Erdogan of launching the military operations against the PKK in a bid to win nationalists' support and discredit a pro-Kurdish party, whose gains in the June elections deprived the AKP of its majority. Last week, Erdogan cited the violence – which has wrecked a nearly three-year old peace process – in stressing the need for a strong government.

The government rejects any political motivation behind the military strikes, insisting that the operations were launched in response to a series of PKK attacks on police and the military.

"The gamble is that the people will go back to the safe embrace of the AKP," said Cornell. "But people will see through it. He is gambling the peace of the country and even the economy for the sake of his personal gains."

In the lead up to the June elections, Erdogan defied rules that require the president to be neutral, and openly campaigned on behalf of the AKP, unleashing fierce attacks on rival parties. Erdogan appeared to have kicked off an official campaign again last week, addressing neighborhood administrators and representatives of non-governmental organizations, and mounting an attack on the pro-Kurdish party's leaders.

"To go the polls at a time when people are being killed every single day can have a downside," said Sinan Ulgen, chairman of the Istanbul-based EDAM think tank and a visiting scholar at Carnegie Europe. "The arithmetic in Parliament won't necessarily change."