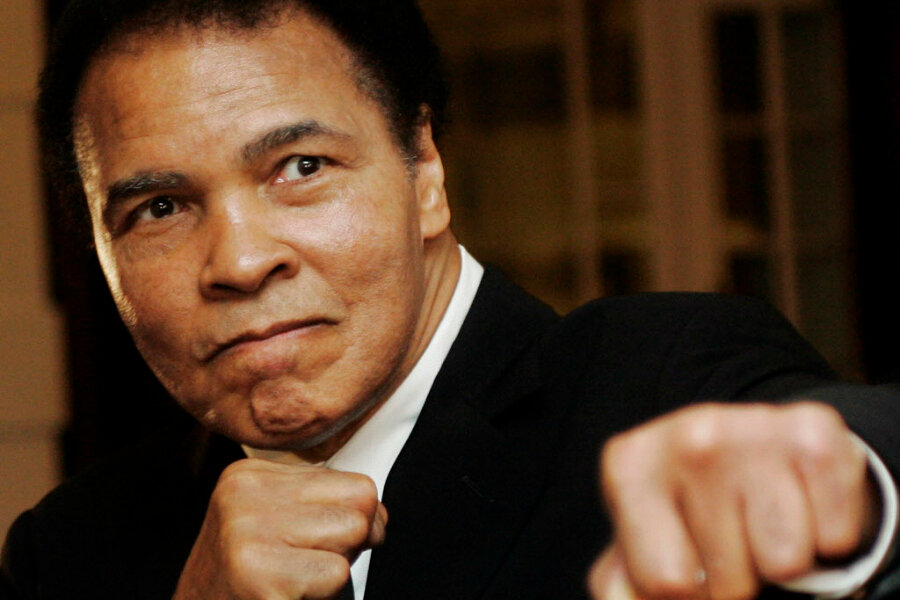

Muhammad Ali: ‘I am America’

Loading...

In 2016, the image of Muhammad Ali isn’t the same as it was for most Americans 50 years ago. And that says something good about US progress on race relations and religious tolerance.

In the 1960s Mr. Ali was a disturbing and sometimes frightening spectacle to Americans, especially white Americans. He was an African-American man who was brash and loud; he bragged and said outrageous things; he was a showman who knew controversy would draw attention to his career.

Born in racially segregated Louisville, Ky., with the given name Cassius Clay, he became an Olympic and professional world champion boxer, earning sobriquets such as “The Louisville Lip,” “Gaseous Clay,” and “The Mouth That Roared.”

Ali, who died June 3, also became a Muslim (and changed his name to Muhammad Ali) at a time when few Americans knew much of anything about that religion.

Perhaps his most controversial stand was as a conscientious objector, refusing to serve in the Vietnam War. But he didn’t flee to Canada; he stood up for what he believed. When asked about the government’s decision to prosecute him as a draft dodger, he said: “They did what they thought was right, and I did what I thought was right.”

Ali was convicted, stripped of his championship title, and wasn’t able to fight for several years. But in 1971 the US Supreme Court ruled unanimously in his favor, overturning his conviction.

Ali helped expand the definition of an American.

“I am America,” he once said. “I am the part you won’t recognize. But get used to me.”

He added:

“Cassius Clay is a slave name. I didn’t choose it, and I don’t want it. I am Muhammad Ali, a free name – it means beloved of God....”

In the 1960s US policy saw Vietnam as a strategic line in the sand drawn to blunt the expansion of Communism. But Ali viewed the war from a different, entirely personal and human perspective:

“My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America,” he said. The Vietnamese “never called me n*****, they never lynched me, they didn’t put no dogs on me, they didn’t rob me of my nationality, rape and kill my mother and father.... How can I shoot them poor people? Just take me to jail.”

In recent decades a lingering illness robbed Ali of his ability to speak forcefully in public. But ironically in his physical weakness he became a more sympathetic character to a nation beginning to mature in its views on race and heal divisions stirred by the Vietnam War.

“A man who views the world the same at 50 as he did at 20 has wasted 30 years of his life,” Ali once said. That might be said of countries, too.

Long before rap and hip hop rose to prominence in American culture, Ali was a proto-rapper. Reading hadn’t come easily to him; his wife, Lonnie, said he compensated by memorizing his own compositions.

He used his rhymes to taunt his opponents. One of his most memorable lines may have originated with his manager, but Ali used it to great effect: “Float like a butterfly/ sting like a bee/ his hands can’t hit what his eyes can’t see.”

By far the most popular show on Broadway today is the hip-hop musical “Hamilton,” which tells the story of Founding Father Alexander Hamilton. Audiences of all ages and ethnicities pack the theater to see a show whose cast is almost exclusively black and Latino playing the part of America’s iconic heroes such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson.

But before there could be a “Hamilton” there had to be an Ali. These lyrics from the musical might just as easily apply to Ali as Hamilton, a man who rose from poverty to make his own mark on US history:

You could never back down

You never learned to take your time!

Oh, Alexander Hamilton (Alexander Hamilton)

When America sings for you

Will they know what you overcame?

Will they know you rewrote the game?

The world will never be the same.