- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Why US-China trade deal is about more than trade

- How PTSD headlines lead to mirage of the ‘broken veteran’

- What equals justice for opioid crisis: Help victims or punish Big Pharma?

- On Memorial Day, an Israeli-Palestinian experiment in reconciliation

- Kicking it with Mia Hamm: My day with women’s soccer royalty

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The view on tariffs from one Massachusetts bike shop

My local bike store – Frank’s Spoke ‘N Wheel in Waltham, Massachusetts – is gearing up for another strong spring season, but there’s a fly in the ointment. Tariffs. At a minute past midnight tonight, the Trump administration is set to raise the tariffs on Chinese bikes from 10% to 25%, barring some last-minute breakthrough. Since 90% of the bikes sold at Frank’s come from China, that means prices are likely to go up.

“I’m realistic,” says owner Frank Spinoza. “It affects everybody, so if you are going to buy a bike, you’re going to be subject to this. [But] the companies figure out a way to roll it in without affecting everything.”

Companies will raise prices on some items; swallow the cost increase themselves on others. Since it’s the season for new models, it will be hard to make an apples-to-apples comparison on many bikes.

All this adds up as an extra tax on U.S. consumers, but it also pressures China to come to terms or risk losing a big chunk of the U.S. bike manufacturing business. Kent International – a U.S. bike importer and distributor – said its Chinese business partners had plans to build a huge factory in Cambodia to avoid the tariffs. Those plans were put on hold when it looked like the U.S. and China were nearing a deal.

Now, who knows? Trek – a big seller at Frank’s – had similar plans.

The point is that trade weaves through our lives in often unseen ways, and the freer it is, the better off we all are. But it also has to be fair.

Our top story today takes a close look at how President Donald Trump and Congress differ on how to make Chinese trade fairer and what can be done to reconcile those differences. Other stories examine what justice should look like in the opioid crisis, the surprisingly healthy recovery rate of PTSD veterans, and what it’s like to kick a ball around with Mia Hamm and other U.S. soccer stars.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Monitor Breakfast

Why US-China trade deal is about more than trade

Fears of a U.S.-China trade war have triggered shudders in financial markets. But the current impasse also exposes a deeper technology rivalry between two nations that are at once interconnected and in competition with each other.

-

Clarence Leong Staff

If trade talks don’t go well President Donald Trump is poised to jack up tariffs on China Friday. Stocks have already tumbled because of the fear. But the United States’ relationship with China is more complex than any bottom line. These two nations, while economically intertwined, are also rivals in a technology race that will shape their respective futures.

That’s one reason why China apparently backtracked on its pledges in the trade talks last week – including new legal protections against the theft of intellectual property. Mr. Trump’s tariff threats followed, and in a rare moment of bipartisanship some of his staunchest Democratic critics rallied behind him. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer tweeted at the president to “Hang tough on China.”

Regardless of what any deal achieves, the two nations appear to have entered a protracted era of competing for technological advantage – and of managing the related tensions in their relationship. “There’s been a gradual awakening,” Democratic Sen. Mark Warner of Virginia said at a Monitor Breakfast with reporters Thursday. But “I wish I had more confidence that the administration understood what was at stake.”

Why US-China trade deal is about more than trade

With trade talks between the United States and China at a make-or-break moment, the news media and investors are focused heavily on President Donald Trump’s threat to jack up tariffs on China Friday if the negotiations don’t go well.

That focus is fair enough. Stocks have already tumbled because of the fear. The tariffs would impose meaningful burdens on businesses and consumers in the world’s two largest economies.

Often left on the sidelines of this discussion, though, is something essential: Those two nations, while economically intertwined, are also rivals in a technology race that will shape their respective futures. That’s one reason why China apparently backtracked on its pledges in the trade talks last week – including new legal protections against the theft of intellectual property, or IP.

Mr. Trump’s tariff threats followed. And he’s not alone in the concern. In fact, while the president’s own checklist with China may revolve heavily around boosting U.S. exports, frustration over leakage of U.S. know-how to China has been rising from the White House to the Pentagon to corporate boardrooms. Some in Congress are, if anything, even more exercised about the issue of technology transfer than Mr. Trump.

“I commend the Trump administration for not allowing the status quo to go on, [but] I wish I had more confidence that the administration understood what was at stake, particularly as we think about technology and innovation,” Sen. Mark Warner, D-Va., said at a Monitor Breakfast with reporters Thursday. “While I think there is finally, finally the beginnings of a strategy on 5G [wireless networks], I think at least the White House was asleep at the switch for the first two years of this administration.”

Senator Warner said “there’s been a gradual awakening” in the private and public sectors to the problem, but that Mr. Trump and to some degree President Barack Obama before him have failed to rally a global coalition to address an issue regarding China that’s global in scope.

Last year, for example, one bill to guard against cyberthreats passed the House on a 362-1 vote.

“This issue of the Chinese forcing American companies to transfer technology or stealing American technology and IP is one of the few issues that enjoys broad bipartisan support,” says Timothy Heath, a security expert at the Rand Corp., a think tank near Washington. “And the difficulty is what do you do about it.”

An era of competition

This week Democratic leaders joined the president in confronting China.

Similarly, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi of California, while questioning some of Mr. Trump’s methods, said Wednesday: “In any trade agreement if you don’t have enforcement, all you’re having is a conversation, a cup of tea.”

“Hang tough on China, President @realDonaldTrump. Don’t back down. Strength is the only way to win with China,” Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer of New York tweeted on Sunday. That came after Mr. Trump had gone to Twitter with a “No!” to a Chinese “attempt to renegotiate.”

The heightened concern about safeguarding U.S. technology doesn’t necessarily mean the Trump administration will win major breakthroughs in a bilateral trade deal.

Rather, regardless of what any deal achieves, the two nations appear to have entered a protracted era of competing for technological advantage, in areas ranging from aerospace and telecommunications to artificial intelligence, all with big military as well as commercial implications. Managing tensions over the issue is an increasingly important part of the U.S.-China relationship, for both sides.

After a year of intense bilateral negotiations, Mr. Trump had voiced the expectation of a deal soon. With the recent setbacks, the question now is whether those hopes can be revived.

As a nudge, Mr. Trump may impose 25% tariffs on $200 billion in Chinese imports as soon as Friday morning. Yet, by some accounts, he’s been open to concessions on the technology issues in order to reach a deal.

“My concern is that he will perhaps agree to a less ambitious agreement in order to close a deal,” says Orit Frenkel, a former director in the Office of the United States Trade Representative and now president of Frenkel Strategies.

Given both his political promises and the rattled investors on Wall Street, “he feels a lot of pressure to have a deal,” she says. “I think he may compromise on some of the more ambitious asks,” including better market access for U.S. cloud-computing firms in China.

Senator Warner voiced similar concern.

“I am extraordinarily afraid that [he] is gonna do some deal with China where he maybe sells another $100-billion-plus of soybeans and declares victory, and we lose the challenge where the game is: intellectual property, emerging technologies like 5G, AI, quantum. And that would be a detriment not only to our country but to the West for decades to come,” he said at the Monitor Breakfast.

The backdrop for his concern: signs of an unprecedented push by China to catapult itself toward leadership in key technologies – a strategy that Beijing calls the “Made in China 2025” initiative. It’s a multipronged effort that has used channels ranging from legitimate investment to espionage.

“China has effectively used stolen IP to grow its gross national product (GNP) and has derived an incalculable near and long-term military advantage from it, thereby altering the calculus of global power,” a recent report from within the U.S. Navy stated.

Complicating the stakes

Although an actual war would likely be catastrophic for each side, both nations as potential adversaries feel the need to safeguard their futures. And the boundary between the economic and military is blurry.

“There’s a lot of different ways that conflicts are playing out,” says Evan Anderson, who leads a private-sector effort in Seattle to safeguard U.S. companies against IP theft. Cyber misinformation campaigns by Russia are one example. Efforts to pluck economic gems from rival nations are another.

“That’s the world that we’re currently living in. And I think we’re getting close to a place where we’ve woken up to that in the Western world,” Mr. Anderson says.

Senator Warner emphasized the goal of moving the discussion beyond the U.S. to include Europe, Japan, South Korea, and others in a multilateral effort – “to go as a group to China to say, ‘China you are a great nation, we want you part of the world community, but you’ve got to play by the rules.’”

It’s a hard task. Pledges have been made by China before, while enforcement and compliance have been lacking, experts say.

“China realizes that being a tech superpower is fundamental to its ambition so it wouldn’t be willing to make genuinely impactful compromises” in trade negotiations, says Alex Joske, who follows security issues related to China at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s International Cyber Policy Centre.

Even if the two nations reach a deal that includes some of the technology issues, “that’s just the beginning of the challenges both in terms of commercial competitiveness” and in the implications for security, human rights, and more, says Graham Webster, a cybersecurity expert at the New America Foundation.

“The reason for that is pretty simple,” he says. “Neither country has figured out what 5G, artificial intelligence, [and other] huge data-driven services are going to mean for our countries.”

In the U.S., some lawmakers including Senator Warner are proposing new laws to grapple with the issues, from privacy to election security. On China, he’s spearheading a bipartisan bill to set up a White House-based office to better track the cyberthreats and other risks inherent in global supply chains for the military.

Others say that, alongside any security measures, the most basic task for America is minding the health of its own society.

“Our country’s job is to do better innovation here at home,” says John Deutch, an MIT scientist and former director of the CIA. “China will overcome us,” he says, “only ... if we don’t pay attention to our own technology and economy.”

How PTSD headlines lead to mirage of the ‘broken veteran’

When former service members commit isolated acts of violence, news coverage linking their behavior to PTSD can reinforce the ‘troubled vet’ stereotype. The reality is less dramatic: Most veterans don’t have PTSD, and most diagnosed with the disorder recover from or manage it.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Recent news coverage of a handful of violent acts committed by Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans in California has emphasized that the men involved struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder after returning from combat.

The reports obscure the reality that hundreds of thousands of veterans of the two wars cope with PTSD while leading the kind of ordinary life that seldom attracts notice. “But that’s not the story that gets the headlines,” says Dan Klutenkamper, a former Army sergeant diagnosed with PTSD.

Craig Bryan, executive director of the National Center for Veterans Studies, suggests that misconceptions about PTSD could remain despite a growing general awareness about the condition. “There’s this idea that anyone who has the diagnosis is broken,” he says. “That isn’t the case.”

The lack of deeper understanding allows “troubled vet” stereotypes to flourish even as veterans occupy a place of veneration in the national culture. “There’s a gap between the military and civilian populations,” says Army Master Sgt. Tom Cruz, who was on the brink of suicide in 2010. “The only way to make that gap smaller is for us to talk about our experiences.”

How PTSD headlines lead to mirage of the ‘broken veteran’

An Iraq War veteran drove his vehicle into a group of pedestrians two weeks ago believing his intended victims were Muslim. A former Marine who served in Afghanistan fatally shot 13 patrons at a country music bar in November. Last spring, an Army veteran who deployed to Afghanistan shot and killed three mental health clinicians at a residential treatment program for former service members.

All three incidents occurred in California, and in each instance, news coverage emphasized that the veteran involved had struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder after returning from war.

The reports hewed to a “troubled veteran” narrative at once familiar and frustrating to Dan Klutenkamper, who has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder linked to his three Army tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. The former sergeant subdues his condition with counseling, exercise, and pet therapy. He has harmed neither himself nor others since his honorable discharge in 2011.

His quiet recovery makes him one of the hundreds of thousands of Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans who cope with PTSD while leading the kind of ordinary life that seldom attracts public notice. They inhabit an obvious yet unseen demographic that, by news standards, draws as much interest as motorists whose daily commute passes without calamity.

“Look at how many combat veterans have come back and haven’t hurt anyone, who have jobs and families, who are doing good,” says Mr. Klutenkamper, who works for a veterans service organization in Washington. “But that’s not the story that gets the headlines, and that’s not the story most people know.”

An estimated 10% to 20% of the 2.77 million men and women who deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan have been diagnosed with PTSD related to their service. Dropping that statistic into reports about isolated acts of violence committed by former service members can distort perceptions, implying that as many as one-fifth of them pose a lethal threat.

Craig Bryan, executive director of the National Center for Veterans Studies at the University of Utah, suggests that reframing the same statistic could alter the image of the veteran as a ticking time bomb. Viewed from another perspective, he explains, 80% to 90% of Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans returned home without PTSD. He adds that the majority of those diagnosed with the condition either recover from or learn to manage their symptoms.

“People have a more general awareness of PTSD than they did a decade ago,” says Dr. Bryan, who deployed to Iraq with the Air Force in 2009. “But there’s this idea that anyone who has the diagnosis is broken. That isn’t the case.”

‘A big disconnect’

The unease clutched Jason Roncoroni as he drove along a rural road in Pennsylvania in 2011 soon after his third tour to Afghanistan with the Army. The severity of his panic attack forced him to pull over, and as he tried to tame his anxiety in the ensuing weeks and months, a sense of failure shadowed him.

“I thought I was falling apart, that I had a character flaw. It was beyond crushing,” says Mr. Roncoroni, who retired from the Army in 2015 at the rank of lieutenant colonel. He draws on that feeling of despair and his recovery in his work as a mental health advocate and life coach for veterans, whose homeland can resemble a foreign country once they hang up their uniforms.

“There’s a big disconnect between what veterans experienced and what civilians know about that experience,” he says. “Going to war changes everyone, but it doesn’t break most of them. It usually makes them stronger. But civilians somehow see combat veterans as damaged goods. They think ‘veteran’ means ‘PTSD.’”

The country’s 18.2 million former service members make up less than 6% of its population, and less than 1% of American adults serve in the military. Their small numbers reduce them to an afterthought in the daily life of most civilians even as veterans occupy a place of veneration in the national culture, celebrated at sporting events and in political campaigns, given priority at restaurants and airports, and lionized in movies and TV shows.

The lack of deeper understanding about veterans and PTSD provides space for stereotypes to flourish. One study found that a majority of employers, while proclaiming a desire to hire veterans, regard them with concern because of doubts about their mental health.

“Whether you see veterans as damaged or heroic, what that does is effectively keep them at arm’s length and makes their individual experience invisible,” says Dr. Shauna Springer. The senior director of suicide prevention with the Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors, a national nonprofit that aids families of deceased service members, she has counseled hundreds of veterans with combat trauma over the past decade.

“We have this practice of singling out veterans, but that pulls them out of their tribe,” she says. “It gives them no way to navigate being human and find their way forward.”

The latest mission

An average of 20 veterans die by suicide each day. Army Master Sgt. Tom Cruz found himself at the precipice in 2010 after three deployments to Iraq. Following an argument with his fiancée, he threatened to end her life and his own, his thoughts knotted by anger and depression.

She stayed composed during the ordeal, talking through his emotions and attempting to calm him. He emerged from his mental haze seven hours later, and in the aftermath, he agreed to receive a psychiatric evaluation and attend counseling. The couple later married, and they since have shared their story with service members, veterans, and civilians across the country.

“There’s a gap between the military and civilian populations in general and on the subject of PTSD in particular,” Sergeant Cruz says. “The only way to make that gap smaller is for us to talk about our experiences and try to help people understand. They need to hear our stories and realize that PTSD is treatable.”

Research shows that the rate of lethal violence remains low among former service members who deployed to war zones. Yet they can struggle with erratic behavior and aggression that contribute to veterans committing a higher rate of violent offenses compared with civilians.

News coverage of combat trauma over the course of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars has broadened awareness of the psychological burdens that troops carry home.

At the same time, resistance to the idea that PTSD can be overcome still exists, including among clinicians.

“I have heard mental health professionals say there are no treatments that work and you can’t get better,” Dr. Bryan says. “That’s just not true. It takes a lot of work in some cases, but most people do recover or keep their symptoms under control.”

Veterans diagnosed with PTSD, if wishing that civilians held a more nuanced view of their condition, assert that the greater onus falls on former service members to confront their trauma. Sergeant Cruz chides veterans who stop receiving treatment after one or two therapy sessions.

“You have to go into counseling kind of like it’s dating,” he says. “If you don’t like one therapist, go find another one. It isn’t always easy to do that, and it’s natural to get frustrated sometimes. But the alternative is not treating your condition, which isn’t really an alternative.”

Mr. Klutenkamper, the former Army sergeant, approaches his ongoing recovery from PTSD as his latest mission, one undertaken as much for himself as for his cohorts, the country’s new generation of veterans. He believes that, as in Iraq and Afghanistan, lives hang in the balance.

“When there’s a situation where a veteran does something bad and it ends up in the news, it casts a stigma over anyone who has PTSD,” he says. “Vietnam veterans went through that, and you can see some of that happening now with us. We have to do better – and that means both veterans and civilians.”

A deeper look

What equals justice for opioid crisis: Help victims or punish Big Pharma?

Three recent developments in lawsuits against opioid manufacturers and distributors point to different models of justice, from criminal prosecution to a $37 million payout without admission of wrongdoing.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

-

Henry Gass Staff writer

What does justice look like in the opioid crisis? Three recent decisions in bellwether lawsuits offer different models of how best to move forward and help individuals and communities rebuild as more than 1,600 lawsuits chug through America’s legal system.

Last week, a Boston jury convicted five executives of opioid manufacturer Insys of racketeering charges, including bribing doctors to prescribe its opioid medication to patients who didn’t need it. West Virginia and Oklahoma have settled lawsuits with McKesson and Purdue Pharma, for $37 million and $270 million respectively. Both companies denied wrongdoing.

In a crisis that has killed about 400,000 Americans and cost the country an estimated $504 billion in 2015 alone, settlements help ease the financial burdens on cities and states. But some say accountability is key.

“You might say one of the essential functions the courts can play is where one party can hold another to account,” says Adam Zimmerman, an associate professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles. “To not have some kind of adjudication about what happened and who did what and who’s responsible, it feels like something’s lost there.”

What equals justice for opioid crisis: Help victims or punish Big Pharma?

As hundreds of lawsuits against opioid manufacturers, distributors, and retailers chug through the U.S. legal system, a trio of recent decisions gives a hint of what may be coming.

On May 2, a Boston jury convicted the onetime billionaire CEO of Insys Therapeutics and four former executives on racketeering charges, in connection with bribing doctors to prescribe opioid medication to patients who didn’t need it and deceiving insurers into paying for it.

“Today’s convictions mark the first successful prosecution of top pharmaceutical executives for crimes related to the illicit marketing and prescribing of opioids,” said United States Attorney Andrew E. Lelling in a statement. “Just as we would street-level drug dealers, we will hold pharmaceutical executives responsible for fueling the opioid epidemic by recklessly and illegally distributing these drugs, especially while conspiring to commit racketeering along the way.”

The same day, West Virginia settled for $37 million with McKesson Corp., the country’s largest pharmaceutical distributor. And in March, Oklahoma settled with manufacturer Purdue Pharma, for $270 million. These settlements could provide a blueprint for more than 1,600 opioid lawsuits pending in courts around the country, most of which have been consolidated under a federal judge in Cleveland.

While the substantial payouts will help states fund treatment and other services, the drug companies involved in both settlements have denied any wrongdoing, and experts say the settlement amounts are not large enough to change corporate behavior. That underscores a key question: What does justice look like? Is it most important that drug companies are held accountable, or compelled to change? That the public understands where the blame lies, and why? Or is it more important that resources to combat the problem are mobilized so the suffering can end?

“You might say one of the essential functions the courts can play is where one party can hold another to account,” says Adam Zimmerman, an associate professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles and an expert in the type of multidistrict litigation (MDL) being used in Cleveland. “To not have some kind of adjudication about what happened and who did what and who’s responsible, it feels like something’s lost there.”

But for communities struggling to cover the tremendous public costs of the opioid crisis, from staffing for 911 calls to overdose-reversal drugs to treatment facilities, settlement payouts provide urgently needed funds.

At the first hearing in the opioid MDL, Judge Dan Polster in Cleveland declared that his objective was “to do something meaningful to abate this crisis, and to do so in 2018.” While he has missed his self-imposed deadline, he has sought a global settlement that would enable communities to rebuild – rather than getting bogged down in years of litigation.

West Virginia Attorney General Patrick Morrisey also sought to settle quickly rather than await the uncertainty and likely delays of a trial. His office says that the McKesson payout is the largest won from any pharmaceutical distributor in the country, and tops the state’s previous settlements with Cardinal Health ($20 million) and Amerisource Bergen ($16 million). In total, the attorney general has now won $84 million from more than a dozen distributors, bolstering his efforts to reduce the supply and demand of opioids.

But for some in West Virginia, the McKesson settlement amount pales in comparison to the devastating impact of the opioid epidemic.

“I thought it was a joke,” says Justin Marcum, a former state legislator and lawyer involved in the MDL. “Big Pharma has basically just ruined America and targeted the innocent, working people.”

West Virginia blamed McKesson for ‘reckless’ actions

Those people include the 400 or so residents of Kermit, a coal town in Mingo County that Mr. Marcum represented in the statehouse until last year.

In 2006 and 2007, McKesson supplied nearly 5 million doses of hydrocodone to a single pharmacy in Kermit. The attorney general’s complaint against McKesson calculates that its supply of hydrocodone and other prescription opioids to Mingo County in 2007 was enough to provide every patient with a dose every hour and 15 minutes. Physicians cannot prescribe more than one dose every four hours.

The complaint charges that the state “has been damaged by the Defendant’s intentional and reckless actions in failing to investigate, report, and cease fulfilling suspicious orders” across the state. McKesson denied it was liable, and the settlement says the deal is not to be construed as an admission by the company of any “wrongdoing, negligence, or failure to comply with any law or regulation.”

Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin, who served as governor from 2005 to 2010, called the settlement a “sweetheart deal” that sells out the state and prevents it from recouping billions of dollars in damages.

Attorney General Morrisey’s press secretary, Curtis Johnson, dismisses that as political hypocrisy.

“While Attorney General Morrisey and subsequent governors have fought to realize historic recoveries from drug distributors, it seems [Mr.] Manchin’s most significant impact in the opioid epidemic was the record breaking numbers of pills he allowed to proliferate throughout the state during his watch,” said Mr. Johnson.

Mr. Morrisey has fashioned himself as a fighter who is cleaning up West Virginia, bringing more accountability and record settlement amounts. He launched the lawsuit against McKesson and sued the Drug Enforcement Administration over quotas on opioid pill production.

But before coming to office, Mr. Morrisey earned $250,000 for lobbying Congress on behalf of an association of drug distributors, though not on opioid issues. His wife, meanwhile, is listed on disclosure forms for lobbying on legislation to tighten restrictions around the prescription opioid hydrocodone, dubbed America’s No. 1 most abused drug. The bill failed, but the federal government enacted the change the following year.

Under Mr. Morrisey, the flow of opioid pills into West Virginia has dropped 35 percent. But overdose deaths have risen to more than 800 per year as addicts have turned to heroin and fentanyl.

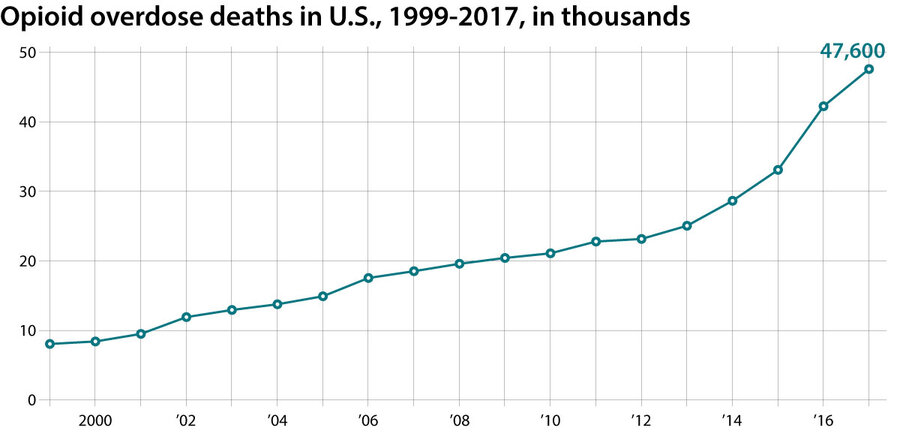

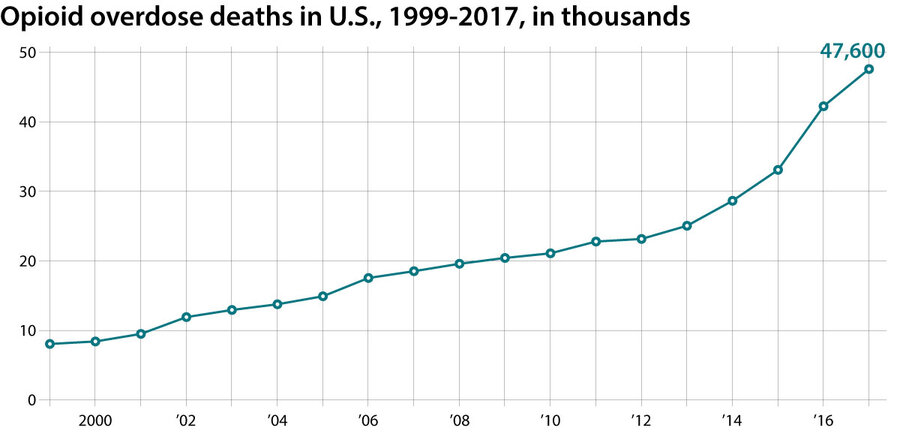

Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics

Chelsea Carter, who was addicted to opioids as a teenager but turned her life around and now serves as lead therapist at Ohio Valley Health in Logan County, says drug companies should acknowledge that they pushed drugs into West Virginia and provide money for treatment. But, she adds, it would be wrong to pin the blame on drug companies alone.

“Everybody has to take responsibility, from the drug companies to the pharmacies to the doctors to the people who take the drugs and get addicted,” she says. “The only difference is they [the drug companies] have the money to try to help the problem instead of making the problem worse.”

Rehabilitating lives, and reputations

McKesson is one of the wealthiest corporations in the world and is ranked sixth on the Fortune 500 list, ahead of Amazon. Its annual revenue in 2018 was $198 billion.

“McKesson is committed to working with others to end this national crisis, however, and is pleased that the settlement provides funding toward initiatives intended to address the opioid epidemic,” the company said in a statement last week, noting that the funds it is paying to West Virginia are aimed at rehabilitation, job training, and mental health, among other areas.

Settlements can have an avalanche effect, providing a framework and baseline that leads to more settlements, which can boost subsequent efforts – or limit them, if early settlements set too low a bar.

“We see this movement [of settlements] as helpful, certainly, but we haven’t even begun to see the types of settlements that are necessary to start to impact this epidemic and to change the practices” of drug manufacturers, distributors, and chain pharmacies, says Jayne Conroy, a partner at Simmons Hanly Conroy, a firm representing plaintiffs in the MDL.

A study from the American Enterprise Institute in Washington estimates the opioid crisis’s annual cost to West Virginia’s economy at more than $8 billion, including lost productivity of those who have died. Nationwide, the crisis has killed 399,202 people from 1999 to 2017, taking an economic toll of more than $500 billion on the country.

“It seems to me even if the drug companies pay a large amount of money, $20 to 30 billion, that’s chicken feed compared to the social costs of the addiction problem,” says Richard Ausness, a professor at the University of Kentucky College of Law who has been following opioid lawsuits across the country.

Oklahoma as a model

The Oklahoma case comes closest to what most experts and lawyers consider the ideal outcome in a settlement of this nature: a large payout that not only compensates plaintiffs but also makes a significant investment toward stemming the crisis that prompted the lawsuit in the first place.

That the case involved Purdue Pharma, maker of the prescription painkiller OxyContin, could be significant. The manufacturer – and its owners, the Sackler family – have emerged as the “the poster child for really bad corporate behavior,” according to Professor Ausness, while distributors like McKesson have had a lower profile.

Part of that is due to their different roles in the supply chain, with Purdue manufacturing opioids and McKesson distributing them. The claims being made against them, and the standards of proof and possible penalties, are thus different as well.

As allegations of Purdue’s role in fueling the opioid epidemic have emerged, there have been protests outside the company’s Connecticut headquarters, museums have begun turning down Sackler family donations, and mothers of victims have asked Harvard University to remove the Sackler family name from campus buildings. Oklahoma had initially sought billions of dollars in damages in its case against Purdue and the other defendants.

For Purdue, Professor Ausness says, the Oklahoma settlement “is a small step, maybe, to rehabilitating their reputation.”

While not a party to the Oklahoma lawsuit against Purdue, the Sackler family voluntarily pledged $75 million toward the addiction research and treatment center being established through the settlement.

“We have profound compassion for those who are affected by addiction and are committed to playing a constructive role in the coordinated effort to save lives,” the family said in a statement after the settlement.

That kind of long-term approach to healing root causes of the crisis did not happen in the $200 billion Big Tobacco settlement in 1998, says Professor Ausness – though funds from the 1998 settlement do fund an anti-smoking advocacy group.

The case for court trials

But other states don’t seem as willing to settle. “We will continue to aggressively pursue our case against Purdue and the Sackler family,” said Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey in a statement to the Monitor. “Families in Massachusetts and across the country deserve answers and accountability from this company and its executives and directors.”

On May 28, Oklahoma is slated to become the first state to go to trial against opioid companies, confronting remaining defendants Johnson & Johnson, Allergan, and Teva Pharmaceuticals USA.

Trials and convictions can bring that sense of accountability, especially when, as is the case with the convictions of the five former Insys executives this month, it could involve prison time. Having to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt is such a high standard, however, that criminal charges have been rare in opioid litigation so far.

“I’m hopeful that we’ll see more criminal convictions of executives for opioid manufacturers in the future,” says Andrew Kolodny, an M.D. at Brandeis University who is involved in the Oklahoma case. “If you want to deter corporations from killing people in their pursuit of profit, I believe criminal prosecutions are required. I don’t think fines and civil litigations are adequate. They can be seen as the cost of doing business.”

Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics

On Memorial Day, an Israeli-Palestinian experiment in reconciliation

On Memorial Day, nations typically grieve for those who sacrificed for the homeland, the political embodiment of a collective identity. Expanding the grief to include an adversary’s fallen is challenging, but for some, healing.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Dina Kraft Correspondent

Israel typically observes Memorial Day with ceremonies extolling sacrifice and perseverance in the face of its enemies. The notion of a joint Israeli-Palestinian ceremony is an outlier – and controversial. Yet from the 200 people who attended the first such event 14 years ago, it has grown to the 9,000 who attended Tuesday evening in a park in Tel Aviv. Among them were about 100 West Bank Palestinians who attended after Israel’s Supreme Court overruled Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s ban on their entering Israel.

The evening was organized by two joint reconciliation groups, Parents Circle Families Forum, a group of Israeli and Palestinian family members who have lost loved ones to the conflict, and Combatants for Peace, made up of former Israeli soldiers and Palestinian militants.

“It has had the resonating effect of bringing hope to people who never usually see the ‘other’ side,” says Robi Damelin, whose son David was killed performing military reserve duty in the West Bank in 2002. “These would usually be the least likely people on earth to have any contact whatsoever, but yet they feel this absolute need to continue with the work of peacemaking.”

On Memorial Day, an Israeli-Palestinian experiment in reconciliation

The brother and sister sat under the night sky with thousands gathered in an exceptional Memorial Day scene: Israelis and Palestinians mourning their war dead together.

Among them were bereaved families like them who lost children, parents, or siblings to the ongoing conflict between their peoples.

In their case, it was their two older brothers who were killed, more than half a century ago, on the same June day during the 1967 Middle East war.

Mira Samet was 17 at the time, and her younger brother was celebrating his 11th birthday, when the news came that their brothers, Amram, 28, and Yochanan, 22, had both been killed.

“This feels like the most sincere and authentic way to share the pain that we have experienced and still experience, sharing the pain with not just people from our side of the tracks, but recognizing the pain of the other side of this conflict,” Mrs. Samet says. “The fact that we can mutually recognize that [shared] pain is possibly the only way to avoid a repetition.”

Controversy

Israel typically observes Memorial Day with ceremonies extolling sacrifice and perseverance in the face of its enemies. The joint Israeli-Palestinian ceremony is an outlier – and controversial.

Yet it has grown steadily, from the 200 people who attended its first event 14 years ago to the 9,000 who attended Tuesday evening. Among them were about 100 West Bank Palestinians who were allowed to attend after Israel’s Supreme Court overruled Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s order barring them from entering Israel.

Mr. Netanyahu lamented the court decision, saying, “There should not be a ceremony that equates the blood of our sons to the blood of terrorists.”

Even among Israel’s center-left there are some opposing the ceremony, saying it should not be held on Israel’s Memorial Day, which they argue is only intended to mourn the country’s own fallen soldiers and victims of war and terror attacks.

As those attending arrived, a group of far-right demonstrators, cordoned off by police, shouted epithets, including, “Traitors, shame on you. Ameleks!” referring to the Biblical enemies of the Israelites.

The evening was organized by two joint reconciliation groups, Parents Circle Families Forum, a group of Israeli and Palestinian family members who have lost loved ones to the conflict, and Combatants for Peace, made up of former Israeli soldiers and Palestinian militants.

This year, events were also held in New York, London, Berlin, and other cities.

“It is being held over the world because it has had the resonating effect of bringing hope to people who never usually see the ‘other’ side,” says Robi Damelin, a spokesperson for the Parents Circle, whose son David was killed at age 28 performing military reserve duty in the West Bank in 2002. “These would usually be the least likely people on earth to have any contact whatsoever, but yet they feel this absolute need to continue with the work of peacemaking.”

Addressing criticism of the event voiced by other bereaved Israeli families, Ms. Damelin says, “I don’t have any right to criticize another parent, but they too should respect our decision.”

Loss in Gaza

The ceremony, held in Hebrew and Arabic with translations broadcast on a large screen, was held on the grassy field of a Tel Aviv park and for the first time was broadcast to Gaza. Just the day before, a 48-hour burst of fighting between Hamas ruled-Gaza and Israel ended in a cease-fire after claiming 25 Palestinian and four Israeli lives. It was the worst fighting since a 2014 war between the sides.

Fathima Muhammadin, a young woman from Gaza who is currently living in Ramallah, in the West Bank, gave a recorded speech that was broadcast to the audience.

“It is difficult to describe life in Gaza. We live under horrific conditions,” she told the crowd, describing the pain of losing her brother to an internal Hamas conflict and her friend to an Israeli sniper. Her friend, Rouzan al-Najjar, a 20-year-old medic, was killed during one of the weekly demonstrations along Israel’s border fence.

Addressing her friend, she said, “I remember when you joked with your friends. ... I will never forget your last breaths saying goodbye to the world. ... We hoped we would live in peace.”

“I know politics are complicated, but let’s put our hearts, minds, and hands together,” she said.

Mohammed Darwish, a Palestinian boy, told of watching his friend and soccer mate die after he was shot in clashes with Israeli soldiers near Bethlehem.

“Stories that are told to us repeatedly about this land supposedly being worth human blood are untrue. I ask future generations to stop adopting this line, which is against the people’s interests,” he said. “I ask you to help return us to the harmony we were rightfully born to.”

Toward changing minds

Among the Israeli speakers was Mika Almog, a writer and co-host of the event and the granddaughter of Shimon Peres, the former Israeli president and prime minister and Nobel Prize winner. She spoke of the evolution of national identity until empathy with the adversary can be achieved.

In an interview, she acknowledges how difficult that path is.

“I approach the whole issue with a great deal of humility ... and an acute awareness of the fact that the story of Israel is the story of the Israel-Palestinian conflict,” she says.

“There is so much pain involved, so much loss. Human beings seek a clear narrative. It is easier for people to find solace in a story that is black and white, that has good guys and bad guys,” she says.

In response to the backlash against the joint ceremony, she wrote an op-ed in the Israeli daily Yediot Ahronot, headlined, “What is so scary?”

“It’s so threatening because it touches upon a truth,” she says, something that requires a major shift in thinking on both sides. “The truth that force is not a solution.”

Kicking it with Mia Hamm: My day with women’s soccer royalty

For most of us, heroes dwell in an untouchable realm. But this month, our reporter got the chance of a lifetime to share the soccer pitch with Mia Hamm, Kristine Lilly, and Tisha Venturini Hoch.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

This is not a dream. I've got a soccer ball at my feet and Kristine Lilly – yes, soccer legend Kristine Lilly – is waving at me from midfield for a pass.

I played soccer for nearly three decades, but it’s been at least six years since I touched a ball in competition. Today, I’m back on the pitch with my idols as part of an adult women’s soccer fantasy camp with Ms. Lilly and fellow World Cup champions Mia Hamm and Tisha Venturini Hoch.

It’s been 20 years since the United States women’s national soccer team defeated China in a nail-biting penalty-kick shootout that captured hearts around the globe and launched a soccer boom in the U.S. Today, many of the ’99ers are still involved in efforts to grow the sport, offering clinics for girls and young women around the country. The children they coach barely recognize them, but for waves of parents – and for us fantasy campers – they are soccer royalty.

Kicking it with Mia Hamm: My day with women’s soccer royalty

I’m doing my best at left defense at the Atlanta Silverbacks soccer stadium. A woman (20 years my junior) is hurtling toward me with the ball, her hair streaking out behind like the tail on a racehorse. I size her up; I decide I can take her. I step up and strike the ball with the inside of my right foot. The ball stops, and momentarily so does the play as the impact of the block throws me off balance and ... I crash to the turf.

She takes off with the ball, but within moments our center defender is sending it back to me. I look up to make a pass. I see Kristine Lilly – yes, soccer legend Kristine Lilly – waving at me from midfield, wide open. Before I lose my nerve, I send her a pass in the air. She lifts her knee and gently settles the ball to the ground with her foot. The play surges toward the other goal.

I raise my hand for a sub. It’s been 2 minutes and 10 seconds, and I’m exhausted.

This is not a dream. I’m at an adult women’s soccer fantasy camp with Ms. Lilly and fellow World Cup champions Mia Hamm and Tisha Venturini Hoch. I’m here with 55 other campers ranging in ages from 23 to 63, and we are ready to party like it’s 1999.

Most professional sports fantasy camps, where participants can get coaching and autographs from the pros, last from three to five days and can cost $3,000 to $10,000. But the target audience is middle-aged men. Few are intended for or coached by women.

So when Ms. Lilly tweeted an announcement for a three-hour women’s soccer fantasy camp for $150 in Atlanta, I immediately began booking my flights.

It’s been 20 years since the United States women’s national soccer team defeated China in a nail-biting penalty-kick shootout, when Brandi Chastain ripped off her shirt in victory, and the record-breaking 90,185 fans at the Rose Bowl Stadium shattered the moon with their cheers.

Today, many of the ’99ers are still involved in efforts to grow the sport. Ms. Lilly, Ms. Hamm, and Ms. Venturini Hoch formed TeamFirst Soccer Academy and offer clinics for girls and young women around the U.S. The children they coach at the clinics barely recognize them as soccer royalty, even though Ms. Lilly remains the most experienced international soccer player (male or female) of all time.

But waves of parents still ask for autographs, and they are the reason for the TeamFirst fantasy camp. They are the ones who first pinned posters of the women’s national team on their bedroom walls. This is what I am thinking about as I pull into the parking lot and a familiar pregame feeling settles over me: I want to throw up.

I played soccer for nearly three decades, but it’s been at least six years since I touched a ball in competition. I step tentatively on the pitch to warm up. My borrowed socks and shinguards are pulled up high, my boots are stiff with age, and the waistband on my shorts feels a tad tight. I clutch my ball to my stomach, trying to settle my nerves.

Soon, a familiar voice commands us to get on the line. It’s Ms. Hamm dressed incognito as a soccer mom in long black pants, a long-sleeve red T-shirt, and a black cap low over her eyes.

“This is how the women’s national team warms up!” she bellows. We laugh nervously and then do a series of gentle runs and calisthenics. We’ve been at it for about 15 minutes and we are wilting. The coaches send us to the pavilion for staff introductions.

I meet Betsy, another camper, wearing a muscle shirt and a weathered tattoo across her right bicep. She tells me she’s been playing soccer for 40 years. She asks my vintage and sniffs, “You had the luxury of Title IX programs,” she says. “If we wanted to play soccer, we had to hunt it out.”

And then it’s back to the pitch. Ms. Hamm demonstrates some drills with the dexterity of a Las Vegas casino dealer. We cycle through stations and then scrimmage. I relax. I’m having fun even though my whole body hurts. Storm clouds gather and lightning forks the sky. We scurry under the pavilion for shelter and dinner. I chat up Michelle Akers, you know, the FIFA Female Player of the Century, over a bowl of tortilla chips. She had shown up as a surprise guest. I tell her I saw her play in an international friendly in 1995 in Decatur, Georgia, on a grassless field leading up to the World Cup in Sweden.

She fixes her steely gaze on my face. “Those ’91 and ’95 fans – those were the hard-core fans.”

I swell with pride.

Now it’s storytime, which feels like a giant sleepover with our soccer idols telling us one inside joke after another. Someone asks, do people still recognize you? Ms. Hamm grins.

The icon who once appeared on a Wheaties box and judo-flipped Michael Jordan in a Gatorade commercial now drives a carpool for her children and their friends as Mrs. Garciaparra, wife of former All-Star shortstop Nomar Garciaparra. She tells us about Angus, a young soccer player, who rides in the back. Ms. Hamm asked him if he’s going to watch the World Cup kicking off on June 7. “There is a World Cup this summer?” Yes, she replied, the Women’s World Cup in France. “They have that?” One of the other kids piped up, “She played in the World Cup!”

Angus paused thoughtfully and asked, “Did you know Mia Hamm?”

We laugh and our faces grow wistful. It’s almost time to leave.

A woman who looks to be about my age raises her hand. “I was in Atlanta for the ’96 Olympics, but I couldn’t afford a ticket,” she says. She watched as much as she could when the U.S. won gold – but NBC broadcast only a few minutes of the game. “I don’t actually have a question,” she says, folding a hand over her heart. “I just wanted to say thank you – for the memories.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Mother’s love and loving our mothers

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The birth of a boy to Britain’s royal family has put the joys of motherhood on international display just in time for Mother’s Day in the U.S. But it also brought questions about how he would be raised by his mother. While many more fathers these days embrace parenting, mothers continue to be a strong influence on their children. In a survey in the U.S., for example, Christian teens identified their mothers as the person they most likely sought out for advice, encouragement, and sympathy – more than fathers. In a 2008 survey of Australian women about the sources for their inspiration, “Virtually all women nominated their mother as role models,” the survey found.

Mother’s Day is often criticized as little more than an excuse to sell cards, flowers, and restaurant meals. That was not the case in 1870 when American activist Julia Ward Howe saw a much different role for mothers. Her “Mother’s Day Proclamation” urged women to become advocates for international peace. Though her concept of the holiday failed, the idea that mothers might play a political or diplomatic role lived on. Women’s groups have been instrumental in peace efforts in many places.

Mother’s love and loving our mothers

The birth of Archie Harrison Mountbatten-Windsor, the latest addition to Britain’s royal family, put the joys of motherhood on international display just in time for Mother’s Day in the U.S. Rumors abounded about how the boy, born Monday to Prince Harry and Meghan Markle, Duchess of Sussex, might be raised. Will they employ an American nanny (gasp!)? How will his mother guide him along the way?

While many more fathers these days embrace the tasks of parenting, mothers continue to be a strong influence on their children. In a new survey in the United States, for example, Christian teens identified their mothers as the person they most likely sought out for advice, encouragement, and sympathy – more than fathers or even friends. Two-thirds said it was their mothers who supported them during their last personal crisis, according to the survey from Barna, a Christian research group. In a 2008 survey of Australian women about the sources for their inspiration, "Virtually all women nominated their mother as role models," the survey found.

Worldwide, the lives of mothers continue to improve. Since 1994 maternal deaths while giving birth have fallen by 40%. Fewer teens, often unprepared for motherhood, are giving birth. But according to the International Labour Organization, women still spend three times as much time on child care and domestic chores as men, though the gap is slowly closing.

Mother’s Day is often criticized as little more than a commercially driven excuse to sell cards, flowers, and restaurant meals. That was not the case in 1870 when American social activist Julia Ward Howe saw a much different role for mothers. Her “Mother’s Day Proclamation” urged women, as nurturers of children, to become advocates for international peace at a time when wars were becoming more violent in scale.

“Arise, all women who have hearts,” she wrote. “Our sons shall not be taken from us to unlearn all that we have been able to teach them of charity, mercy and patience. We, women of one country, will be too tender of those of another country, to allow our sons to be trained to injure theirs.” She urged mothers to “solemnly take council with each other as to the means whereby the great human family can live in peace, man as the brother of man.”

Though her concept of the holiday failed, the idea that mothers might play a political or diplomatic role lived on. Women’s groups have been instrumental in peace efforts in places from Northern Ireland and the Korean Peninsula to Nigeria, Liberia, and Yemen. Sixteen women have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Motherhood itself can provide great training for political leadership. “It teaches you sacrifice. It certainly teaches you negotiation because you’re always negotiating between children,” Utah’s first and only woman governor, Olene Walker, once told an interviewer.

Choosing to raise a child can come with a high price for women who seek other pursuits. One recent study connects first-time motherhood with a 30% drop in future pay, money that may never be recouped over the course of a career. (Another study suggests fatherhood provides an opposite 20% bump in pay for men.)

The more society puts a value on motherhood – even if only for one day a year – the more it can find ways to help mothers gain and not lose from their central role as shapers of future, and perhaps peaceful, generations.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

To end painful memories

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Pamela Cook

After suffering from PTSD for years, today’s contributor turned to God in heartfelt prayer. The realization that God’s peace and goodness are permanent freed her from the mental baggage without a long recovery or rebuilding process.

To end painful memories

In childhood, I had an experience that left me feeling unworthy, afraid, and burdened with a painful memory. For years I suffered from diagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD – a problem cropping up frequently in the news lately, especially in stories of individuals returning from military service in war zones. Years of psychotherapy and medication did nothing to lessen the pain or diminish the effect of the memory that disturbed me.

Then, yearning to be free of this ball and chain dragging me down, I turned to God in heartfelt, silent prayer.

What came to me was a rather shocking realization: The only place this experience was taking place was in my thinking. The haunting memory was not a current experience; it was simply a current thought. A few years earlier, I’d started to study Christian Science. From this I’d been learning that everyone, as God’s spiritual offspring, reflects all the goodness that God is, and this was a solid, spiritual basis for rejecting troubling thoughts and claiming my freedom from suffering. Even though the memory’s hold on me felt very real, it had no legitimate power to hurt me because it was not part of my true, God-given identity.

I realized at that moment that the memory was a thought I didn’t have to nurture and hang on to as part of me forever. I could choose to discard it. So that’s what I did. I resolved to release it. That very day, it lost its hold on me. Within a couple of days, the sense of burden and pain was gone completely.

And after all those years, suddenly my sense of self-worth began to change because the starting point for defining myself had changed from that of a person weighed down by a horrible past experience to that of an individual living in the now, one with God, loved and protected by divine Love, always.

There wasn’t a long recovery or rebuilding process; I simply felt like myself, without the baggage of memories that had seemed to define me for so long. Internally, I was jumping for joy with gratitude to God and for Christian Science for bringing me this release from mental bondage. I saw the key was realizing that there had only ever been one reality, and that is the reality of God’s permanent goodness.

The spiritual lesson I’d learned is one that each one of us has access to: namely, that nothing from the past has the authority to disturb one’s peace, infiltrate one’s thinking, and define one’s present identity. Jesus said, “The kingdom of God is within you” (Luke 17:21). To me, that means that each individual’s consciousness is stocked full with heavenly, Godlike thoughts. The kingdom of God could not possibly include painful memories. Instead, this kingdom of God – this infinite realm we all live in and where God, the divine Mind, is the supreme governor – is naturally filled with peace, security, and serenity. And no matter how traumatic a memory may seem, God holds your hand and guides you away from it and toward Him.

It’s liberating to know that one doesn’t have to wait for new experimental drugs, medical advances, or a certain amount of time to pass to let go of painful remembrances. We each have a choice, every moment, about what we entertain in our thoughts, and we can choose to discard thoughts that aren’t from God. Thoughts that are joy-filled and peaceful are derived from God and therefore are permanent and real. These are the keepers.

As we let thoughts of peace – thoughts of God – fill us up, our day-to-day experiences actually reflect this serenity. We become increasingly joyful and secure. Peace becomes the norm. Now becomes the only influence and the only reality of existence. And painful memories fade away.

Adapted from an article published in the July 6, 2009, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

What a long neck you have

A look ahead

That’s a wrap for today. Come back tomorrow when we examine the latest twists and turns in the Iran nuclear deal.