- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- China’s media push: How Beijing’s messaging winds up around the world

- Russian missiles for Turkey? What’s at stake as collision looms.

- When a city of canals floods, what happens to waterway shantytowns?

- On July 4, memories of a veteran who sought to bridge differences

- Seaweed fudge, anyone? Maine lobstermen try a new, watery crop.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

In border crisis, a false choice between compassion and rule of law

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Welcome to your Monitor Daily. In today’s issue, we look at a new front for Chinese propaganda, what missiles tell us about Turkey’s view of itself, a different way to address floods in the developing world, a Korean War vet-turned-bridge-builder, and seaweed for those with a sweet tooth.

First, let’s turn to a news item that broke yesterday.

At one refugee processing center, inhabitants spoke of “cramped rooms, filthy toilets, suicide attempts, and frequent canteen fights, all punctuated with apparently random deportation swoops.” At another, the mud was mixed with human waste and rotting food. Hearing people screaming in food lines and seeing fences topped by razor wire, one asylum-seeker there said the government “does not see us as human.”

These stories sound as though they could have come from a report released yesterday detailing the conditions for detained migrants in U.S. Border Patrol stations. One senior official said the situation was so dire it is a “ticking time bomb.”

But the examples above come from Germany and Greece – two other countries struggling to cope with the world’s current mass migrations. And they are a reminder of both the stress the migrations are putting on arrival countries and of the urgent need to find solutions that maintain the dignity and humanity of those seeking help.

The situation is not unprecedented. The United States faced similar challenges in the mid-1990s. A solution came from addressing the actual problems – adding resources where needed, using detentions where wise, and thinking carefully about what claims asylum should include, notes an article in Vox. That means deciding that the choice between compassion and rule of law must be both.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

China’s media push: How Beijing’s messaging winds up around the world

China is expanding its media presence abroad, and that is changing the message that many Chinese emigrants hear. It’s one small part of Beijing’s multibillion-dollar bid for global influence.

It’s called the “Grand Overseas Propaganda Campaign”: Over the past decade, China’s Communist Party has aimed to bolster its image and soft power abroad by spreading its messaging via websites, newspapers, and TV. Such outlets broadcast Beijing-slanted news, for example by omitting reports about last month’s protests in Hong Kong, or that criticize China’s human rights violations.

“Before, the West was coming to influence China,” says Zhang Weiguo, a Chinese journalist who lives in Sacramento, California. “So now China’s strategy is to flip this upside down, and use Communist Party ideology to change the West.”

Increasingly, Beijing’s media push goes beyond Chinese-speaking communities. Since China launched the $7 billion campaign in 2009, it has moved swiftly to expand its English-language media in the United States. China Daily is a state-owned English newspaper and China Global Television Network reaches 30 million U.S. households with English programs. Both CGTN and China Daily are registered as foreign agents in the U.S., as required of groups representing foreign powers.

Still, some independent Chinese-language media retain a voice. Assunta Ng, an independent Chinese American publisher in Seattle, says, “We criticize China and Taiwan whenever we like.”

China’s media push: How Beijing’s messaging winds up around the world

As Hong Kong protesters staged huge marches last month over a bill to allow extradition to China, some of Seattle’s Chinese-speaking residents knew nothing about the demonstrations.

One reason: For their news, they rely on China’s propaganda outlets, which didn’t cover the large-scale, politically sensitive demonstrations in the semi-autonomous southern Chinese port city.

“I didn’t hear about any protests in Hong Kong,” says a health worker who moved to Seattle 11 years ago from China’s Guangdong Province, which borders Hong Kong. “I get all my news online from Sina.com – it’s very popular here,” she says, referring to the website of a Chinese technology company that runs news from China’s state-owned media. She declined to be quoted by name.

Over the past decade, the proliferation inside the United States of China’s official news – both in Chinese and English – is part of what the Communist Party calls its “Grand Overseas Propaganda Campaign,” aimed at “grabbing the right to speak” from Western media, according to official Chinese media reports and government websites.

The campaign aims to bolster China’s image and soft power abroad by spreading party messaging among the large Chinese diaspora in the U.S. and other countries – as well as, increasingly, foreigners. But it focuses heavily on millions of Chinese in communities abroad, aiming to mold overseas organizations into “propaganda bases” for China’s “united front,” according to a state-run publication cited in a 2017 report by Anne-Marie Brady, an expert on Chinese politics.

The campaign involves not just promoting pro-Beijing information, but discouraging negative reports. Censorship extends into social media, and is strengthened by Chinese platforms’ suppression of content that authorities deem negative. For example, some U.S. citizens have recently had messages or entire accounts censored on the popular Chinese messaging app WeChat, owned by the firm Tencent.

“It’s quite shocking to me that China’s Great Firewall is coming to the U.S. in digital form,” says George Shen, a technology consultant from Newton, Mass., who had his WeChat accounts banned last month. “It’s a very stealthy, sophisticated censorship. … They are filtering out your messages without even telling you,” he says.

Bankrolled with billions of dollars of government funds, the strategy goes beyond establishing Chinese media entities abroad, to leasing or purchasing foreign news outlets and hiring foreign reporters. This tactic, known as “borrowing a boat to go out on the ocean” – or buying a boat, as the case may be – is aimed at offering a cloak of credibility.

Even as China expands its channels to American audiences, it is increasing restrictions on U.S. media in China. Last month, Chinese authorities blocked several more U.S. media outlets from the internet in China, including the websites of The Washington Post, The Christian Science Monitor, and NBC News.

“The expansion of the CCP’s [Chinese Communist Party’s] media influence is a global campaign, and the United States is among its targets,” writes Sarah Cook, senior research analyst for East Asia at Freedom House, a U.S. government-funded NGO, in a report released last month. “The results have already affected the news consumption of millions of Americans.”

Last September prior to U.S. midterm elections, for example, China’s state-run media placed an advertising section in the Des Moines Register warning of the harm to soybean farmers of the U.S.-China trade conflict – an apparent effort to influence Iowa voters.

The spread of pro-Beijing content, often coupled with a lack of transparency over its origins, makes “the potential for political, electoral manipulation very strong,” Ms. Cook says in an interview.

In an herbal medicine shop in Seattle’s Chinatown, China’s state-owned China Central Television (CCTV) news beams from a flat-screen TV near the entry, as it does from many businesses in the historic district. Shopkeeper Jianhe Hang says he tunes into China’s government broadcasts every day.

Mr. Hang arrived in Seattle 10 years ago from Guangdong to join relatives, and has a green card, but like other residents of the district, he’s cautious about voicing opinions to a reporter. Asked about the protests in Hong Kong, he says he’s aware of them, but declines to say more. “I am middle of the road. I don’t support them, and I don’t oppose.”

CCTV dominates the Chinese-language cable offerings in the U.S., where it is available in about 90 million cable-watching households, far more than the estimated 4 million to 5 million Chinese Americans in the country.

“Here, every day I can watch CCTV or Phoenix TV [a pro-Beijing outlet based in Hong Kong], and when I go to the market I can buy Chinese state newspapers,” says Zhang Weiguo, a Chinese journalist in Sacramento, who was jailed and exiled by Chinese authorities.

The growing saturation of China’s official media over the past decade means some Chinese speakers in the U.S., particularly recent arrivals from China, “are very close to Beijing – in a lot of places their thinking is totally aligned,” he says.

Increasingly, however, Beijing’s media push goes beyond Chinese-speaking communities. Since China launched its overseas propaganda campaign in 2009, with a budget of $7 billion, it has moved swiftly to expand its English-language media in the U.S.

China Daily, a state-owned English newspaper, established a U.S. edition in 2009 with newspaper vending boxes on the streets from Seattle to New York City. China Daily did not respond to calls and email queries about its current U.S. circulation, but in 2012 it was reportedly 170,000. It has also placed paid “China Watch” advertising supplements in U.S. newspapers including The Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post. China Daily has spent nearly $20 million on U.S. influence since 2016, according to U.S. Justice Department reports.

China Global Television Network (CGTN), part of the international arm of China’s state-owned CCTV, reaches 30 million U.S. households with English programs. Recently, CGTN anchor Liu Xin made one of the first major appearances for a Chinese media personality on mainstream U.S. television – a debate on U.S.-China trade with Fox News host Trish Regan.

Both CGTN and China Daily are registered as foreign agents in the U.S., as required of groups representing foreign powers. As a result of its registration this year, CGTN last month was denied press credentials by the Senate Press Gallery. The Justice Department reportedly asked the state-run Xinhua News Agency, which has several U.S. offices, to register as well. Asked about the matter, the Justice Department declined to comment.

China’s involvement is sometimes opaque. For example, pro-China radio content in English is broadcast from about 30 radio stations across the U.S. – from Boston to Los Angeles. The stations are owned or their airtime leased by a U.S. company that is, in turn, controlled by the state-run China Radio International. In another case, a Beijing-linked firm bought a radio station in Mexico and is broadcasting Chinese-language content throughout Southern California, although the FCC has not yet approved the sale.

Such outlets broadcast Beijing-slanted news, for example by omitting reports that criticize China’s human rights violations, while presenting the official line on sensitive issues such as China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea.

“Before, the West was coming to influence China,” says Mr. Zhang, “so now China’s strategy is to flip this upside down, and use Communist Party ideology to change the West.”

So far, China’s rising media presence in the U.S. has been felt most strongly among the Chinese diaspora, while having a relatively limited impact on average Americans, experts say. But the networks give China “the potential of mobilizing Chinese Americans and Americans alike to espouse policies counter to US interest,” according to a report by prominent China scholars published last year by the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. “The constant drumbeat of anti-American reporting in pro-Beijing media outlets headquartered in the United States creates an unhealthy environment.”

Although U.S. authorities have limited tools for countering this influence in an open society, they can work to determine the ownership of Chinese companies buying U.S.-based media and require foreign-controlled media that promote a government agenda to register as foreign agents, the report concludes.

Relaxing near the Chinese pavilion at Seattle’s Hing Hay Park after a 10-hour shift at a local eatery, Tan Ancun reads a free copy of the pro-Beijing newspaper Qiao Bao. “I only read free newspapers,” says Mr. Tan, a slight man with graying hair who emigrated four years ago from Guangdong. Hard-pressed to cover rent for his small room, Mr. Tan says he can’t afford to pay for news.

A U.S. Chinese-language paper with a circulation of about 100,000 in 17 U.S. cities, Qiao Bao has an office in Bellevue, Washington, and also runs a Mandarin-language radio station in Seattle. Qiao Bao’s content echoes China’s messaging – for example in a story Tuesday condemning Hong Kong’s protests. Its founders and other personnel have close ties to Beijing; some formerly worked for state-run media in China.

“Qiao Bao is all over Chinatown,” says Assunta Ng, a veteran Chinese American newswoman in Seattle. “A lot of people like to get freebies, so they don’t care if they read propaganda,” says Ms. Ng, who was born in Guangdong, raised in Hong Kong, and has an M.A. in communications from the University of Washington.

Still, some independent Chinese-language media retain a voice in U.S. cities. For example, Ms. Ng publishes Seattle China Post, which she founded 37 years ago after she noticed Chinatown residents relying on news from a street-corner bulletin board.

Like other independent publishers, Ms. Ng has come under pressure from China’s growing media presence in the U.S. But she’s confident her paper’s combination of hard news and strong local coverage will continue to appeal to subscribers.

“We criticize China and Taiwan whenever we like,” she says, wearing a pink jacket and a baseball cap. Working late as her newspaper goes to press, she sits near a wall lined with prizes and awards for her service. “We are pro-community,” she says.

Russian missiles for Turkey? What’s at stake as collision looms.

As U.S. ties with Turkey have frayed, Russia has stepped in. Now a Russian missile deal has become a pivotal issue of Turkish identity.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The United States and Turkey have been on a collision course for years. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s increasingly authoritarian rule and the close U.S. alliance with Syrian Kurdish militias, whom Turkey regards as terrorists, are among the main irritants.

Now the collision is imminent. NATO member Turkey, which has been on tap to purchase 100 of the Pentagon’s F-35 stealth fighters, is a week away from taking delivery of Russian missiles that are part of a new air defense system.

While President Donald Trump made a last-minute effort in Osaka, Japan, to ease the crisis, the missile purchase risks unraveling the NATO alliance and could bring sanctions from Congress against Turkey’s weakened economy. Yet Mr. Erdoğan seems resolved to move ahead with the deal, because, analysts say, it speaks to Turkey’s long-term direction and even its identity.

“It is an existential question,” says Aslı Aydıntaşbaş at the European Council on Foreign Relations. “Turkey sees that as its ticket to a more independent policy, but in reality it is probably going to make Turkey beholden to Russia far more than it is prepared to be.”

Russian missiles for Turkey? What’s at stake as collision looms.

As the United States and NATO-ally Turkey braced for an inevitable collision over Turkey’s decision to buy a Russian-made air defense system, a ray of hope appeared to emerge from the sidelines of the G-20 summit in Osaka, Japan.

Could the two countries avert a crisis that risks unraveling the NATO alliance, as Turkey turns away from the West and toward Russia for part of its defense needs?

Deliveries of the Russian S-400 missile system are to begin in a week, Turkey says. But U.S. officials have been warning for months that if Turkey goes through with the $2.5 billion purchase, it will result in U.S. sanctions against Turkey’s already weak economy and jeopardize its role in the Pentagon’s F-35 stealth fighter program and purchase of 100 of the planes.

But then President Donald Trump appeared to ease the pressure, after meeting with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Japan.

Mr. Trump blamed Barack Obama for forcing Turkey’s turn to Russia, saying his predecessor blocked sales of the U.S. Patriot missile system – without mentioning that Turkey had, in fact, rejected the sale three times, because its demands for technology and joint production were not met.

Mr. Erdoğan had not been “treated fairly” and wanted the American missile, Mr. Trump stated. The Turkish leader is “a NATO member, and he’s someone I’ve become friendly with, and you have to treat people fairly. ... You can’t do business that way. It’s not good.”

Turkish identity

But can such diplomatic overtures paper over the ever-widening U.S.-Turkey chasm? Analysts say that is not likely because the proposed purchase speaks to fundamental issues about Turkey’s long-term direction and even its identity. Mr. Erdoğan is sticking with a crucial decision that could hamper NATO weapons systems integration and prove an intelligence bonanza for Russia. And it is the U.S. Congress, not Mr. Trump, that will impose sanctions.

More broadly, Mr. Erdoğan’s decision is not only technical but also political, and designed to signal Turkey’s unhappiness with the U.S. and other NATO allies on a host of issues, from criticism of Mr. Erdoğan’s authoritarian rule at home, to his troops’ role in Syria.

“If Turkey proceeds with the S-400 Russian missile system – and all indications are that it will – I think it’s the beginning of the unraveling of Turkey’s longtime relationship with NATO,” says Fadi Hakura, a Turkey expert at the Chatham House think tank in London.

“It’s not happened previously where one NATO member imposes military and economic sanctions on another,” says Mr. Hakura. “The key player in this is not President Trump, it’s Congress. There is total bipartisan consensus [to penalize] Turkey. This is one of the few issues attracting bipartisan consensus in Washington.”

According to Eliot Engel, the Democratic chair of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, this is a “black-and-white issue” for Congress.

“Either Mr. Erdoğan cancels the Russian deal, or he doesn’t,” Representative Engel of New York said in the House in early June after passage of a resolution condemning the planned purchase. “There is no future for Turkey having both Russian weapons and American F-35s. There is no third option. There’s no path for mitigation that will allow Turkey to have its cake and eat it, too.”

‘Existential question’

Indeed, U.S.-Turkey relations have been marked more by clashes than harmony since 2013, when the Obama White House criticized Mr. Erdoğan’s handling of the Gezi Park protests in Istanbul and press freedom.

A host of problems have since marred relations, including, crucially in Turkey’s calculation, devoted U.S. military support for Kurdish militias in northern Syria that battled the Islamic State (ISIS). The Syrian Kurds are linked to militants of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party in Turkey who are fighting Ankara.

In early June, then-acting U.S. defense chief Patrick Shanahan issued an ultimatum to Turkey’s defense minister, warning that if the S-400 deal with Moscow was not scrapped by July 31, the U.S. would shut Turkey out of the F-35 project, which is now being rolled out across Europe. Turkish pilots already in training on the F-35 have been withdrawn from classes in the U.S.

Sanctions will follow, the Pentagon warned, in compliance with U.S. legislation designed to hamper the Russian defense industry.

“It is an existential question. Something like this couldn’t have happened a decade ago, or even five years ago,” says Aslı Aydıntaşbaş, a Turkey specialist at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

“Yes, it does underline Turkey’s yearning to emerge as a more independent global power, no longer entirely dependent on the United States,” says Ms. Aydınstaşbaş.

“Turkey sees that as its ticket to a more independent policy, but in reality it is probably going to make Turkey beholden to Russia far more than it is prepared to be,” she says. “And Turkey’s exit from the West would be a very painful exercise, both in terms of our military culture, and our economy. So S-400s are not just about S-400s. It’s about the identity of Turkey and its place in the world.”

American support for Syrian Kurdish militias, whom Turkey considers to be “terrorists,” has especially grated on Ankara. U.S. and Turkish troops deployed cheek by jowl in Syria, ostensibly fighting with the same anti-ISIS objectives, have at times come close to open conflict.

Unlikely shift toward Russia

But another aim of Turkey in Syria has for years been to topple the regime of Bashar al-Assad. And that is directly opposed to the goal of Russia, which has deployed air and ground forces, alongside Iranian troops and proxy forces, to preserve the Assad regime.

Turkey has nevertheless worked with both Russia and Iran, agreeing in 2017 to create and monitor several de-escalation zones in Syria, in a deal that deliberately shut out the U.S.

Yet Turkey’s shift toward Russia could not be more unlikely, since Ankara “feels threatened by its massive neighbor” to the north, say Soner Çağaptay, a Turkey expert at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, and Andy Taylor, a former congressional staffer, in a recent analysis in The Hill.

“Between the 17th and 20th centuries the Ottoman and Russian empires were deadly rivals,” they note. “Until the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917, Turks and Russians fought 17 major wars, which the Turks overall lost.”

Turkey’s decision to join NATO “was driven by its fear of Russia,” they say, adding that Stalin’s demand for some of Turkey’s land in 1946 prompted Ankara to join the Western alliance in 1952.

“Of course, [Russian President Vladimir] Putin is happy to sell weapons to a NATO member to drive a wedge in the alliance,” the analysts note. “Moscow can use the S-400 system to conduct invaluable intelligence-gathering efforts against the F-35,” a project Turkey has been a partner with from the start.

Turkey-Russia relations took a bitter turn in November 2015, when Turkey shot down a Russian jet fighter that had crossed from Syria into its airspace for 17 seconds. Mr. Putin called it “a stab in the back by the accomplices of terrorists” and imposed sanctions on Turkey.

Decline of a ‘trustable ally’

While that relationship has clearly been patched up – and several million Russian citizens have been allowed again to each year enjoy their vacations on Turkey’s Mediterranean coast – the S-400 deal marks a concrete repudiation by Turkey of the U.S.

“It is certainly going to be quite a historic alienation between the two, if indeed Turkey does go through with the purchase,” says Sinan Ülgen, a former Turkish diplomat and head of the Center for Economics and Foreign Policy Studies, a think tank in Istanbul.

“The technical aspect is it has taken the U.S. far too long a time to come up with a package that could satisfy Turkey’s needs,” says Mr. Ülgen. “But this has come on top of a political atmosphere which has been quite poisonous, in the sense that there has been a very clear and widespread erosion of trust in the U.S. commitment to Turkey, and Turkey’s security.”

The result is that the U.S., instead of being viewed as a “trustable ally,” is seen in Ankara as disregarding Turkey’s core national security interests “by aligning itself with and weaponizing” Kurdish militias in Syria, says Mr. Ülgen. “It’s the trust void that’s been left by the U.S., which has allowed Russia to become so aligned with Turkey over this time, and that’s quite remarkable.”

Climate realities

When a city of canals floods, what happens to waterway shantytowns?

Many Southeast Asian nations have turned to the bulldozer to manage big-city slums. But some flood-control efforts are finding success in a new tactic: actually talking to communities. This story is part of an occasional Monitor series on “Climate Realities.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

-

By Trudy Harris Contributor

Offer a slum dweller a new home close to his old one, and he still might not want to move. Sopon Lee helped convince 650 other residents along a Bangkok canal that it was a good idea. After allaying fears about size, cost, and whether the authorities could be trusted, he, with the others, finally reached agreement with the government.

The slum’s relocation is a successful example of authorities working with the poorest people to protect them from the rising threat of floods. Asia’s megacities have struggled with unchecked development, poor urban planning, and exploding populations. Climate change is exacerbating the problem. But there’s been a shift toward resilience projects that work closely with marginalized groups.

As Bangkok has boomed, residents along the canal say they have watched as condos and office towers have been thrown up with little regard for the environment, their waste dumped directly into once-pristine waters. “This canal ... we used to drink from it. We remember when there were rice fields here and buffaloes grazing,” says Narong Sangwew, a retired printing press worker.

Mr. Sopon says he feels that with the relocation, he has secured his family’s future. “And we still have water views,” he says.

When a city of canals floods, what happens to waterway shantytowns?

Sopon Lee recalls the dirty, stinking water that regularly swept through his wooden home in a slum on the edge of a Bangkok canal. Thailand’s annual monsoon rains often brought flooding to the city, forcing members of his family to grab their sodden belongings and race to higher ground.

“It was part of normal life for us,” he says, remembering how the rubbish-filled water reached waist level one year. “Then you repair and rebuild as best you can.”

When the government came knocking three years ago with a flood prevention plan to raze the illegal settlement and build new homes a few yards back from the water, Mr. Sopon saw a rare opportunity.

“We had no legal right to be there, no security, so we never knew what the future would bring. This was our chance,” says Mr. Sopon, whose family had lived along the canal rent-free for years.

But there was a catch. Mr. Sopon and other community elders needed to convince all 650 residents of their community to agree to the plan, or the deal was off. After 12 months of tirelessly working to allay fears not only about the size and cost of the new homes, but also about whether the authorities could be trusted, they finally reached agreement.

“There were so many meetings, day and night. We visited other sites; we talked with government officials to get questions answered. It was exhausting. But I was retired; I had the time,” Mr. Sopon says, sitting with other elders on the small front porch of one of the new homes, surrounded by potted plants and wind chimes.

The slum’s relocation along Lat Phrao Canal is a successful example of authorities working with the poorest people to protect them from the rising threat of floods. Asia’s megacities have long struggled to cope with flooding because of unchecked development, poor urban planning, and exploding populations. Experts in the region say they are seeing a shift toward projects that directly involve marginalized communities, as authorities try to build resilience across their cities.

But climate change is exacerbating the problem, bringing rising sea levels and abnormal weather patterns like increased rainfall and more powerful typhoons. In recent years, Bangkok has been dredging canals, moving slums that block them, and building tunnels and barriers in efforts to prevent the kind of disastrous floods that hit the Thai capital in 2011, killing more than 800 people nationwide. The experts warn much more needs to be done, especially to protect the most vulnerable people.

Uniquely positioned to flood

“Almost every major Asian city in this region has suffered major flooding in the last 10 years,” says Abhas Jha, a manager in the region for urban development and disaster risk at the World Bank. “The situation will become worse. What we used to call a one-in-a-100-year event is happening more frequently,” he says. “The wet places will become wetter and the dry places will become drier.”

East Asian cities face high risks of natural disasters and climate change, according to a World Bank report. Cities like Bangkok; Manila, Philippines; and Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, are all low-lying, coastal behemoths, built in the deltas of major river systems.

But Bangkok, with a population of 10 million, is also sinking under the weight of its own frenetic development. The city is built on what was once marshland, which includes a layer of soft clay. Natural land subsidence, or sinking, has been made worse by decades of overpumping of groundwater, a practice that authorities have successfully stemmed. Without groundwater, the clay dries out, leaving it susceptible to more subsidence.

Concrete urban jungle has also taken over natural drainage sites and green areas, preventing rain from replenishing the groundwater. Instead of seeping into the ground, much washes into the canals and underground drainage network that once managed the flow of Bangkok’s mighty Chao Phraya River. Some of these are now clogged with garbage, or have been developed over.

Bangkok risks being submerged in less than 15 years unless urgent action is taken, a 2015 study by Thailand’s National Reform Council warned.

As with most flood disasters, poor populations are likely to be hit hardest. Across Asia, millions of rural poor people have flocked to the cities seeking better-paying jobs resulting from booming development, squeezing into whatever housing they can afford. East Asia is home to the world’s largest slum population of 250 million people, many of whom live in poor-quality housing on flood-prone land with limited access to basic services, the 2017 World Bank report said.

In Indonesia, court battle over forced moves

In another of the world’s fastest-sinking cities, Jakarta, Indonesia, officials have also tried moving slums, homes for tens of thousands often clustered on stilts along the Indonesian capital’s canals, clogging the waterways.

Residents of these informal settlements, or kampungs, complain of being forced to move to new homes far from their jobs and question officials’ motives behind the resettlements, in a city where land is scarce and corruption a problem. Authorities say the relocations are critical for cleaning up the waterways to prevent regular flooding and protect everyone, but they have been met with angry resistance. One kampung won a court case against the government trying to push the residents out.

“There can’t be top-down solutions to these problems. If you want this to be successful, communities need to be consulted, to be more included in the decisions,” says Elisa Sutanudjaja, a kampung advocate and executive director of the Rujak Center for Urban Studies in Jakarta.

“Most of them want to stay together. There is a social cohesion and structure to these communities that is a traditional part of Indonesian life,” says Ms. Sutanudjaja, adding that communities were confident in a more inclusive approach from the city’s new governor.

In a sign of just how dire the situation has become in Jakarta, Indonesian President Joko Widodo announced in April he was considering moving the entire capital somewhere else. Jakarta, choked with traffic and pollution, sits on a swampy plain on the shores of the Java Sea. North Jakarta has sunk by an alarming 8 feet in the last 10 years. At that rate, 95% of north Jakarta will be underwater by 2050, affecting more than a million people, according to the World Economic Forum.

Ms. Sutanudjaja, however, scoffs at the president’s suggestion. With a population of almost 30 million, including the Greater Jakarta area, too many livelihoods are at stake. “This has been raised many times before, but I don’t believe it will happen,” she says.

Despite the kampungs’ battles, Mr. Jha from the World Bank says extensive consultation with poor communities about protection from flooding and other climate change impacts is increasing in the region. A shift is occurring in the way authorities tackle the problem, he says, because of increasing evidence that community-led development projects work. He points to large-scale upgrading of slums in Vietnam as well as Indonesia that included connecting them to basic services (rather than bulldozing and forcing people to relocate to new homes, often miles away), improving drainage, and involving local community networks in disaster risk management plans.

Green spaces and better planning

Not every community along the Lat Phrao Canal has agreed to move. But Bangkok’s slum project has been largely successful because it prioritized community participation, including empowering members and addressing their specific needs, a study by the United Kingdom-based development think tank Overseas Development Institute found.

More work is needed, however, including to ensure that early warning systems reach poor communities and that they are clear on what action to take. While big infrastructure projects like dikes and underground drainage are important, so too are green spaces, rainwater harvesting, and other innovative, cost-effective solutions, experts say.

A park with playgrounds and lawns opened at a university in Bangkok last year with an unusual feature – an underground container that, along with a pond, can hold a million gallons of water if flooding hits. The new green haven is a big deal in Bangkok, which has among the lowest ratios of green space in Asia, 3.3 square meters (35.5 square feet) per person compared with 13.5 (145 square feet) for Shanghai and 19.3 (207.7 square feet) for Washington, D.C., the Siemens-sponsored Green City Index showed.

More urban planning is also needed based on research, mapping, and understanding of the risks, and those policies need to be enforced so that property is not built on flood plains and on earthquake fault lines, Mr. Jha adds. “There are a great number of people and assets in harm’s way.” The floods that swept Thailand in 2011 caused an estimated $46.5 billion in losses and damages, with factories and industrial estates inundated, residents evacuated, and planes grounded at Bangkok’s second, smaller airport.

Mr. Jha applauded the painstaking work by Bangkok’s Community Organizations Development Institute (CODI), a government agency charged with ushering through the rebuilding and relocation of some 7,000 poor households along a large stretch of the Lat Phrao Canal. The project, however, was running behind schedule and would not be finished for another two to three years, according to officials.

Lengthy negotiations with the communities were partly responsible for the overrun, with some reluctant to move, unsure of whether they could afford the nominal cost of the new homes, Bangkok’s chief resilience officer, Supachai Tantikom, explains.

“They cannot go on living there. It’s dangerous because it’s blocking the water. But we can’t do the dredging and we can’t build the walls and we can’t build the new homes until they agree to move,” says Dr. Supachai, a civil engineer who oversees flood upgrading projects.

Residents were partly blamed for the 2011 floods because their rubbish blocked the murky waterways, causing them to overflow, he adds.

It's the upscale growth, too

Mr. Sopon and the other elders dismiss this as scapegoating. As Bangkok has boomed over the years, they say they have watched in dismay as condos and office towers have been thrown up with little regard for the environment, their waste dumped directly into what were once pristine waters.

“This canal used to be our lifeline. We used to drink from it. We remember when there were rice fields here and buffaloes grazing,” says Narong Sangwew, a retired printing press worker who started squatting on the state land on the canal’s edge years ago, building a home as best he could and raising his family.

Mr. Narong and the others say they have no regrets about accepting the government’s offer. They pay about 1,000 baht ($30) a month toward the 200,000 baht ($6,500) construction cost of their new two-bedroom homes, after taking out low-interest loans through CODI. Mr. Sopon, who used to own a small business selling papaya salad before retiring, shares two slightly bigger homes with his family of nine, including four grown sons.

Mr. Sopon says he feels like he has secured a future for them. Under the deal, he and his family will eventually own the homes and can live there for at least another 30 years, paying 40 baht ($1.25) a month to the city in land rent.

“And we still have water views,” he says.

This story was produced with support from an Energy Foundation grant to cover the environment.

A letter from

On July 4, memories of a veteran who sought to bridge differences

A trip to Seoul reminded the author of his former editor, a Korean War veteran who became Nevada’s governor and who believed that a sense of independence can coexist with a desire to unite.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

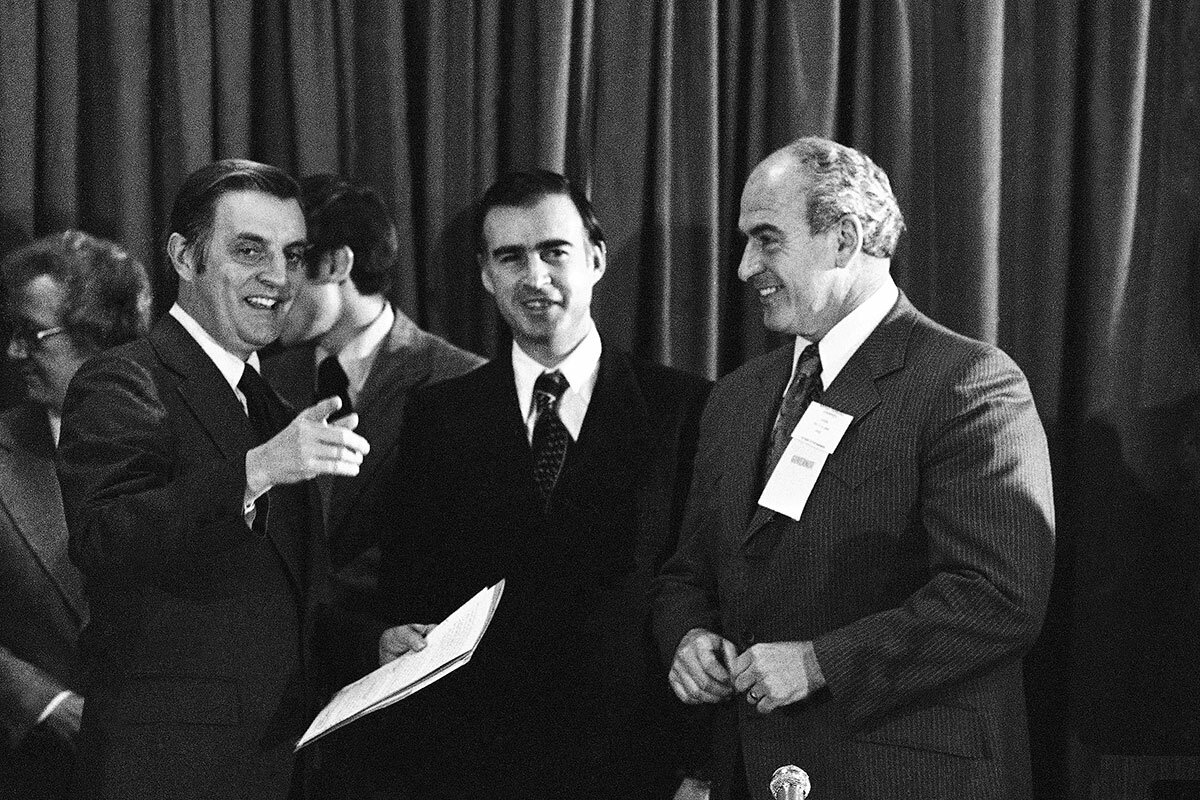

In 1997, I went to work for the Las Vegas Sun, where a former two-term Nevada governor named Mike O’Callaghan served as the executive editor.

With his highway-wide shoulders and oil-drum chest, “Governor,” as most people called him, brought to mind an aircraft carrier cutting through high seas when he strode across the newsroom. He radiated what could be described as an imposing benevolence, resolutely devoted to the principles of inclusion, tolerance, and fairness – and unafraid to raise his booming baritone to emphasize his point.

The Korean War forged the raw toughness that Mike had displayed as a teenage boxer in Wisconsin. The Army platoon leader proved his mettle in 1953, when an enemy mortar round shredded his left leg and killed a U.S. soldier next to him. Refusing medical evacuation, he cinched his leg with a telephone wire and crawled back to the unit command post. Over the next three hours he directed his platoon’s movements, giving orders by phone until North Korean troops retreated.

Mike’s actions earned him the Silver Star. While a partial leg amputation ended his boxing dreams, the slight limp caused by his prosthetic leg neither slowed his gait nor dimmed his sense of purpose. As he once told a reporter, “There were plenty of things I wanted to do, and doggone it, you don’t have to have a foot to be a governor.”

On July 4, memories of a veteran who sought to bridge differences

A statue outside Korea’s national war museum depicts two soldiers standing atop a granite dome as they share an embrace that at once suggests love, anguish, and longing. The two men are brothers and adversaries – one fighting for South Korea, the other for North Korea – whose sibling bond conquers their military allegiances. As they clutch each other, their feet remain on opposite sides of a crack that runs across the dome, a tableau symbolic of two countries bound by history, geography, and family yet divided by war.

I saw the sculpture on a recent visit to Seoul, and its portrayal of aspirational unity reminded me of one of the few Korean War veterans I have known. His service on behalf of another country pursuing its independence endures as a feat of valor and sacrifice. But as July Fourth approaches, and as America at this moment appears unified only in the pages of the Constitution, it is his life’s work after the military that offers a useful lesson for a polarized nation.

In 1997, I went to work for the Las Vegas Sun, where a former two-term Nevada governor named Mike O’Callaghan served as the executive editor. The title sounded much too tame for a man of his physical and figurative stature.

In bearing, with his highway-wide shoulders and oil-drum chest, “Governor,” as most people called him, brought to mind an aircraft carrier cutting through high seas when he strode across the newsroom. In spirit, he radiated what could be described as an imposing benevolence, resolutely devoted to the principles of inclusion, tolerance, and fairness – and unafraid to raise his booming baritone to emphasize his point.

The Korean War forged the raw toughness that Mike had displayed as a teenage boxer in his native Wisconsin. The Army platoon leader proved his mettle in 1953, when an enemy mortar round shredded his left leg and killed a U.S. soldier next to him. Refusing medical evacuation, he cinched his leg with a telephone wire and crawled back to the unit command post. Over the next three hours he directed his platoon’s movements, giving orders by phone until North Korean troops retreated.

Mike’s actions earned him the Silver Star, and while a partial leg amputation ended his boxing dreams, he chased his future without any loss of optimism, ambition, or Irish cheer. The slight limp caused by his prosthetic leg neither slowed his gait nor dimmed his sense of purpose. As he once told a reporter, “There were plenty of things I wanted to do, and doggone it, you don’t have to have a foot to be a governor.”

He made a few stops between the Army and Nevada’s top office, including high school teacher and boxing coach, county probation officer, and state health and welfare official. In 1970, running as a Democrat for governor, Mike steered his low-budget, grassroots campaign to an upset over the favored Republican candidate. Four years later, he received twice as many votes as his two opponents combined.

His bipartisan appeal testified to a rapport with voters across ideological and demographic lines as he moved between the state’s halls of power and its small towns. He possessed a cinematic presence and back story but showed a common man’s touch, enabling him to advance causes ranging from affordable housing and rural schools to child welfare and prisoners’ rights.

He practiced politics with great energy and profound humility, aware of his mandate as much as his flaws. He brought those traits – along with his salty sense of humor and cackling laugh – to the newsroom after leaving office. Writing a regular column for the Sun, he continued to advocate for the dispossessed with blunt candor, guided by the moral compass that led him to South Korea decades earlier.

In his columns, as in war and politics, Mike sought to uphold liberty and opportunity as ideals without boundaries. He supported Falun Gong members persecuted in China, Kurds in northern Iraq victimized by Saddam Hussein, and Mexican journalists targeted by drug cartels and police alike. In a 1999 piece, he called for increased U.S. aid to Central America, a region familiar to him from numerous visits, to alleviate the privations of countries “grasping for democratic principles and economic survival.”

Evidence of Mike’s legacy of public service abounds in and around Las Vegas, where a middle school and a military medical center bear his name. In 2004, months after his death, the governors of Nevada and Arizona announced that a new bridge spanning the Colorado River between the states would be named for him and Pat Tillman, the Army infantryman and former NFL player killed in Afghanistan that year.

The tribute to Mike’s memory aligns with his unrelenting efforts to connect with people and bridge the differences between them. On the Fourth of July, in a spectacle that can seem like a grand contradiction, we celebrate the nation’s independence by coming together. But as he showed throughout his life, and as represented by two Korean brothers hugging on the battlefield of a war not yet over, a belief in freedom can coexist with a desire to unite.

Seaweed fudge, anyone? Maine lobstermen try a new, watery crop.

Kelp may be coming to a seafood menu near you. Not just because it’s healthy and climate-friendly, but because it could change the industry.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

Joe Young symbolizes a transformation on the Maine coast. After relying on lobstering for almost 40 years, he now grows oysters and also kelp in a tidal pool on his property. And, even as lobster remains king of Maine’s maritime industry, Mr. Young plans to expand as part of a booming aquaculture business in the state.

Cultivating seaweed allows fishermen a hedge against the uncertainties of lobstering. And seaweed beds absorb the carbon dioxide that has made waters less habitable for marine life, according to the Bigelow Laboratory of Ocean Sciences. The World Bank has touted nutrient-rich seaweed as one potential solution to global food insecurity.

“So many more people than you would think are really open-minded about seaweed,” says Josh Rogers, who owns Heritage Seaweed, a Portland, Maine, shop. Some evidence: This May’s kelp harvest coincided with Maine’s first Seaweed Week, which drew foodies to a crawl of more than 60 Portland eateries that offered seaweed-inspired delights.

“We have a seaweed fudge,” Mr. Rogers says. “That always makes people giggle.”

Seaweed fudge, anyone? Maine lobstermen try a new, watery crop.

When Luke’s Lobster opened a wharfside restaurant in Portland, Maine, in early June, there was more to the menu than the brand’s signature crustacean. For one, a summer salad features a kelp buttermilk dressing.

Luke’s Lobster co-founder Ben Conniff sings seaweed’s praises. “It’s great for the environment. It’s extremely healthy,” he says.

The dish is emblematic of a turning tide in Maine. The seafood company prides itself on the sustainable business it has built with Maine fishermen, who increasingly look to aquatic crops like kelp for off-season income. Mr. Conniff says he wants to help “ease people into the conversation about how great [seaweed] is.”

In a state where lobster is king – an industry with a billion-dollar economic impact each year – aquaculture, or the farming of aquatic species, is becoming a contender.

Maine has around 150 aquaculture lease sites for operations that include oysters, finfish, and seaweed. In the decade since 2007, the total economic impact of Maine’s aquaculture has almost tripled, to $137 million, according to a report from the University of Maine.

China and Indonesia produce the bulk of the world’s seaweed, mostly for human consumption. But Maine has become an aquaculture leader in the U.S. as home to the country’s first commercial seaweed farm, Atlantic Sea Farms. It helps that seaweed aquaculture tends to be less capital-intensive than fishing.

Off-season income aside, cultivating seaweed allows fishermen a hedge against lobster’s uncertain future. With changing industry practices, a bait crisis, and warming waters affecting lobster fishing, an environmentally friendly crop like cultivated kelp seems like a good option to many.

“I don’t think anyone is disputing that the Gulf of Maine is a different place now than it was 30 years ago,” says Merritt Carey, board member of the Maine Seaweed Council and founder of Tenants Harbor Fisherman’s Co-op.

Wild kelp isn’t immune to that shifting world, either. Climate change and invasive species are contributing to the decline of Maine’s southern seaweed beds, according to researchers.

But that’s where kelp farmers can help: Cultivated beds absorb the carbon dioxide that has made waters less habitable for marine life, according to the Bigelow Laboratory of Ocean Sciences. And seaweed is a “zero-input crop” that doesn’t need pesticides or soil to flourish. The World Bank has touted nutrient-rich seaweed as one potential solution to global food insecurity.

Despite its sustainability, aquaculture comes with controversy. Lobstermen compete to fish in places that are also desirable as aquaculture sites, and homeowners are protective of their waterfront properties. Maine’s Department of Marine Resources might amend its rules regulating the size and location of aquaculture leases.

Training programs, such as the Maine Sea Grant’s “Aquaculture in Shared Waters,” help fishermen transition into aquaculture. The 11-week course offers aquaculture training that covers topics like site selection and financial management.

“There’s a very strong and very intentional outcome of this – meeting your colleagues and making a professional network. That helps to build community,” says program leader Dana Morse, extension associate for the Maine Sea Grant program and University of Maine Cooperative Extension.

Joe Young from Corea, Maine, was an inaugural student. A sixth-generation fisherman, Mr. Young relied on lobstering for almost 40 years. But in 2013, he realized his lucrative industry was weathering some uncertainty.

News of the Aquaculture in Shared Waters program piqued his curiosity; he cobbled together enough fishermen to hold a class. Now semi-retired, he grows oysters and kelp in a tidal pool on his property and plans to expand.

Mainers are keen to spread the gospel of seaweed to grow local demand. Luke’s Lobster provided a grant through its Keeper Fund to research kelp’s ability to curb ocean acidification.

This May’s kelp harvest coincided with Maine’s – and possibly the country’s – first Seaweed Week, a food crawl of more than 60 Portland eateries that offered seaweed-inspired delights. Josh Rogers, the event’s producer, said foodies came from as far away as Washington, D.C.

“So many more people than you would think are really open-minded about seaweed,” says Mr. Rogers, who sells homemade seaweed tea. “They just don’t know how to get it into their diets.”

Mr. Rogers owns Heritage Seaweed, a Portland shop that claims to be the first of its kind in North America dedicated to the trending algae. He says people are familiar with seaweed cosmetics, but surprised to find it in so many edible forms.

“We have a seaweed fudge,” he says. “That always makes people giggle.”

Editor’s note: This article has been updated to clarify the economic impact of Maine’s lobster industry.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Take a cue from Britain on sports gambling

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In the year since the U.S. Supreme Court allowed states to legalize betting on sports, at least a dozen states have rushed to pass legislation. Yet Americans should hit the pause button in light of the following news: In Britain, where youth have found it relatively easy to gamble on sports online, the government is setting up the first health clinic for children with gambling addiction. In recent years, the number of children with a gambling problem in the U.K. has exploded.

Britain is not leaving the problem to chance. A new law requires gambling companies to check on a person’s age before taking his or her money. The industry has agreed to ban advertising around live sports. And with evidence of more children committing suicide after running up gambling debts, Parliament has begun a probe of the gaming industry.

Meanwhile in the United States, 18 states have so far rejected sports betting legalization bills for 2019. Perhaps those states have concerns about luring children to gamble on sports. They also may want to keep encouraging young people to pursue careers and wealth through education and talent rather than a superstitious belief in luck.

Take a cue from Britain on sports gambling

In the year since the U.S. Supreme Court allowed states to legalize betting on sports, at least a dozen states have rushed to pass legislation. More tax-hungry states may follow. Yet Americans should hit the pause button in light of the following news from across the pond:

In Britain, where youth have found it relatively easy to gamble on sports online, the government is setting up the first health clinic for children with gambling addiction. Another dozen clinics are in the works. Children as young as 13 will be eligible for treatment.

In recent years, the number of children with a gambling problem in the U.K. has exploded. More than 55,000 are problem gamblers, the government estimates, or about 1.7% of children under 16. Overall, more children place bets than consume alcohol, tobacco, or illegal drugs.

Britain is not leaving the problem to chance. A new law requires gambling companies to check on a person’s age before taking his or her money. The industry has agreed to ban advertising around live sports during the daytime. And with evidence of more children committing suicide after running up gambling debts, Parliament has begun a probe of the gaming industry.

In one smart move, the Gambling Commission recently conducted a survey of children who have chosen not to gamble in order to better understand their moral reasoning. The hope is that those who abstain can influence those inclined to gamble. This is a welcome step in preventing children from trusting their lives to the deceptive promises of chance.

In its latest move, the government has twisted the arm of the five leading gambling companies to contribute more revenue in support of safer gambling. Their contributions will rise from the current 0.1% of gross gaming yield to 1.0% by 2023. The industry will also increase spending on gambling addiction treatment services and help better identify problem gamblers.

“As [gambling] technology advances, we will need to be even more sophisticated in how we respond,” says Britain’s culture secretary, Jeremy Wright.

Meanwhile in the United States, 18 states have so far rejected sports betting legalization bills for 2019, according to The Associated Press. Perhaps legislators in those states have concerns about luring children to gamble on sports. They also may want to keep encouraging young people to pursue careers and wealth through education and talent rather than a superstitious belief in luck.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Finding true independence

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Allison J. Rose-Sonnesyn

With Independence Day in the United States just around the corner, here are two healings that shed light on what it means to truly be free – and our God-given ability to experience that.

Finding true independence

Many countries around the world annually commemorate a time when citizens shook off the bonds of political tyranny to establish the freedom to be their own people or nation. Independence Day in my country is special to me, because it causes me to express gratitude for all the ways in which I can freely think and act to stand up for good and love in the world.

Yet even in countries that have made gains in overcoming political oppression, it too often seems that freedom, whether from disease, uncertainty, or other burdens, is under threat. Can we truly find freedom from these types of bondage? I had an experience that helped me see that yes, we can!

Following a terrorist attack on my country, I started experiencing recurring severe headaches and a tremendous fear of crossing and being trapped on a particular tall bridge on my commute to work. I began to pray for myself, as I had found helpful in prior challenges. I’d seen before that instead of feeling helpless or in bondage to my body or my environment, I could take a stand for my spiritual independence, my God-given freedom to live and think beyond what the situation seemed to be – to look to God for a truer, spiritual understanding of reality.

As I prayed, a passage from the Bible especially spoke to me: “Where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is liberty” (II Corinthians 3:17). I reasoned that since God is everywhere and is all good, as Christian Science explains, there isn’t any place God’s children can be where they are in bondage to evil.

I also prayed with a passage in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science and founder of this newspaper: “Love is the liberator” (p. 225). God, who the Bible tells us is Love itself, liberates us from anything unlike Love because God is the only legitimate power and presence. Evil is not more real or powerful than God, good.

Cherishing this focus for my prayers, I felt free to express joy and love in my daily activities. I realized that fear or pain could not usurp my God-given ability to reflect such qualities. Very soon, the headaches ceased, and a short time later my fear of crossing the bridge disappeared, too. I’ve since crossed that bridge many times without fear. And this experience has also enabled me to help others looking for freedom from illness and fear in their lives.

For me, the Bible has been an indispensable guide in thinking more deeply about freedom, which is a central theme throughout its pages. In the Old Testament, for instance, are accounts of Moses, who led the children of Israel out of slavery in Egypt; Elisha, who saved a woman’s sons from being taken into slavery; and Daniel, who found freedom in the face of an unjust death sentence.

Christ Jesus brought the concept of freedom to an even higher level. He showed that true freedom isn’t limited to the ability to do and move as one wants; it is the right to understand one’s true nature as God’s spiritual image and likeness. Jesus explained, “Ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free” (John 8:32). All of us are the sons and daughters of God, and so are inherently free, not confined by mortal, material concepts about life and existence. This is the basis of our permanent and unimpeachable freedom.

This spiritual sense of freedom is not limited to any one group of individuals. No one is ever left out of it. We are all able to live our nature as the children of God’s creating – expressed in health, joy, love, peace, and an abundance of good – and to overcome limitations that would impede or prevent us from doing so.

Science and Health encourages: “Citizens of the world, accept the ‘glorious liberty of the children of God,’ and be free! This is your divine right” (p. 227). We can claim for ourselves and everyone our God-given freedom – on Independence Day and every day.

A message of love

Total eclipse

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. On Friday, we’ll look at solutions to the rural housing shortage.

Tomorrow is a federal holiday in the United States, so we’ll have a special holiday feature – a video of a small slice of American culture. Our photo editor, Alfredo Sosa, attends a robust demonstration of cannons and other Civil War-era firearms in the Virginia countryside.