- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Rent as high as an elephant’s eye? Housing shortage hits rural US.

- Money first, politics later. Did Bahrain advance Mideast peace?

- Why Queens is the ‘Noah’s ark of languages’

- Trying to change Congress, starting with the lowest rung: interns

- A visit to Korea’s DMZ: Fast food, a pirate ship – and a bit of hope

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

For World Cup finals, US women ready to ‘fight until the end’

Welcome to your Daily. Today we look at solutions to the rural housing crisis and perhaps to Middle East strife, the proliferation of spoken languages in one New York borough, how interns could change Congress, and an oasis of hope on the Korean Peninsula.

First, consider this quote: “Fight until the end.”

That’s from Rose Lavelle, star midfielder for the U.S. women’s national soccer team. Speaking after the Americans beat England to reach Sunday’s World Cup final, she talked about her and her teammates’ relentlessness. That’s why they’ve reached the edge of this championship, she said.

The importance of perseverance is an old sports cliché. It’s up there with “the best defense is a good offense” and “there’s no ‘I’ in team.”

But in this case it looks to be true. Relentlessness is a matter of preparation as much as will. And the U.S. team has assembled more players who are bigger, more focused, and more experienced than their competition is. In a series of tough games they’ve proved that if one part weakens, they can throw in another and keep coming, no matter what.

That’s no guarantee of finals victory. England had chances to beat them. The Netherlands has a 1-in-3 chance to win the final, according to data site FiveThirtyEight.

What it does mean is the current U.S. team is today’s incarnation of a movement, a deep and long-standing dominant force. It’s not novel that America is the favorite. If the U.S. women win, it would be their fourth title in eight World Cups. They’ve won gold in four out of six Olympics.

So watch the game and remember this is not a team, or a sport, on the verge of a breakthrough. It is a dynasty – and deserves to be treated as such.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Rent as high as an elephant’s eye? Housing shortage hits rural US.

Mention a housing shortage, and we’re likely to think of challenges in New York or San Francisco. Our writer on the farm beat found it’s just as big an issue on the wide-open Plains.

Drywall is going up on new homes in Gothenburg, Nebraska, and it can’t happen fast enough. The small community (pop. 3,448) doesn’t have enough housing to offer workers who are considering moving in.

It sounds paradoxical for a region with abundant land, but parts of rural America are facing a housing shortage. It spans the spectrum from low-income families to midlevel professionals. The good news: Washington as well as state governments are focused on the problem.

“We were seeing our local businesses lose out on all of the candidates that wanted to come to work in our community but just couldn’t find housing,” says Nate Wyatt, president of Gothenburg’s economic development group.

Part of the solution is finding what to do with low-income rural apartment complexes, where the maturing of Agriculture Department loans means landlords are no longer required to hold down rents. Another challenge: It costs more to build in rural Nebraska than in Omaha. Gothenburg is taking matters into its own hands. Experts say other communities need to build the local expertise to bring in new housing.

Rent as high as an elephant’s eye? Housing shortage hits rural US.

In one unfinished house of this cul-de-sac, the drywall is so new you can still smell the joint compound. In another, a carpenter works on beveling the counter of the kitchen island.

“We were desperate,” says Verlin Janssen, a city councilman for Gothenburg, of the mini building boom. There was so little available housing in this community of 3,448 that nurses, factory workers, managers, and others were turning down job offers to relocate here because they couldn’t find houses to live in.

It may be hard to believe, given the region’s overall population decline, cheap labor, and abundant land, but parts of rural America are struggling with a housing shortage. It affects everyone from low-income families to midlevel professionals. Even executives of hospitals and banks have to consider whether there are appropriate homes for them – or places to rent while they build a home – when they contemplate a move to rural areas.

Fortunately, in the past year, the plight of these home-starved communities has gained national attention and broad bipartisan agreement that something should be done, even if Democrats and Republicans disagree on solutions.

“I see more attention to housing policy at the federal and presidential level in the last six months than I've seen cumulatively my whole career,” says David Lipsetz, CEO of the Housing Assistance Council, a Washington-based nonprofit focused on rural housing and communities. In the last presidential election, when the Democratic platform made a single mention of rural housing, “my heart started beating: ‘Oh my gosh, somebody mentioned housing!’” he says. “And now it's like every candidate out there has programs that they're pushing that are so detailed I have to study up to figure out what they're talking about. That gives me great hope.”

Solutions are complicated because housing policy is complex and rural America itself is so diverse.

In vast stretches of countryside, small isolated communities continue a decline that’s gone on 80 years or more and may be accelerating. In addition to all the usual forces of rural depopulation – such as the departure of young people for better educational opportunities, the disappearance or relocation of factories to bigger places, the ongoing consolidation of agriculture into bigger and fewer farms – these rural counties face a demographic threat. They’re increasingly unable to offset outmigration with modest population growth because births no longer outnumber deaths in these aging centers, writes Kenneth Johnson, a demographer at the University of New Hampshire in Durham, in a recent report. “Nonmetropolitan counties are experiencing absolute population decline for the first time in America’s history.”

But it’s not bleak for all of rural America. Counties on the edge of metro areas, those with amenities such as rural colleges or tourist attractions like mountains or lakes, and those communities that consolidate the commerce of faltering small towns into a single location are stable or growing. And it’s in these areas that the shortage of homes is focused.

Some of the biggest challenges involve low-income rental housing.

That’s because 50-year federal loans made to build rental complexes in rural America are starting to mature. And when they mature, landlords of those complexes are no longer bound by federal rules mandating that they stay low-rent, and tenants no longer receive federal assistance with their rent. Then one of two things happens: Landlords either jack up the rent (if they’re in a thriving area) or they close the facility, because they can’t afford to run it when their tenants lose federal assistance.

It’s a problem that will build in coming years, ultimately affecting more than 415,000 affordable homes in rural America.

Why rents surged in one Kentucky county

And the problem isn’t limited to subsidized units. Already, 1 in 4 rural renters spends more than half his or her income on housing, according to the Urban Institute. In a 2018 study, the Washington-based think tank found more than 150 rural counties with younger, poorer, more diverse, and yet growing populations where all rental housing is in short supply. Some of these are because of special situations.

In one eastern Kentucky county, rents are on the rise because the local medical facility has a large intern program that brings in medical students. But because of the mountainous terrain, space is limited to build more housing, says Corianne Scally, a researcher at the Urban Institute. In touristed rural areas, outsiders snap up second homes, which raises the price of land and homes, sometimes beyond what locals can afford.

Then there’s the lack of contractors and the cost of building materials, often trucked in from urban areas, which ironically make it more expensive to build in rural Nebraska than in Omaha.

“I have five critical access hospitals in my little legislative district,” says Nebraska state Sen. Matt Williams, whose hometown is Gothenburg. “Every one of them is shorthanded of workforce right now.” One reason, he says, is the lack of housing for workers.

Two years ago, he got a bill passed that used $8 million in state funds to offer matching grants to Nebraska communities if they would build homes. The program got twice the number of applicants than it had funding for. “We were just overwhelmed,” Senator Williams says. The state has gone on this past legislative year to pass tax breaks for building homes in rural areas.

Rising demand, thanks to Doritos

Gothenburg didn’t wait for state or federal help. Home to a Frito-Lay plant – “If you eat a Dorito, Tostito or Frito west of the Mississippi River, it most likely came from the Gothenburg facility,” the community proudly proclaims – the town wasn’t bringing in enough talent.

“We were seeing our local businesses lose out on all of the candidates that wanted to come to work in our community but just couldn't find housing,” says Nate Wyatt, president of the Gothenburg Improvement Company, the local economic development group.

The GIC has worked hard to bring companies to town, including the Frito-Lay plant. So the group approached a contractor with the proposition that it would make up for any losses if he would build six homes in town. Those houses were snapped up, and none of the 20 or so local residents who signed loan guarantees up to $10,000 has had to write a check.

Now, the city’s community redevelopment authority has used a similar guarantee to get two contractors to build seven two- and three-bedroom homes in the cul-de-sac, which are now rising from their foundations. The cost: about $240,000 each. Three are already sold, according to Mr. Wyatt, and another two are spoken for.

The city dipped deep into its budget to extend Avenue J several blocks to give access to the cul-de-sac. “We’re not going to make any money on this,” says Mr. Janssen, the city councilman. But already, he’s looking longingly at the acreage across the street as a place to put in even more homes.

Some progress for rural homes at the federal level has come at the regulatory level, where the Trump administration is pushing the federally sponsored home mortgage guarantors Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to guarantee more rural rental projects. And states may come up with more incentives.

But the biggest progress will come only when local communities have the local organizations and know-how to apply for and manage the state and federal resources that will be made available, says Mr. Lipsetz of the Housing Assistance Council.

And a little of Gothenburg’s derring-do might not hurt.

The Explainer

Money first, politics later. Did Bahrain advance Mideast peace?

After decades of disappointments in Middle East peacemaking, it’s easy to be skeptical about new initiatives. President Trump has vowed to succeed where others have failed. Here's how his approach is working.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Taylor Luck Correspondent

The Bahrain conference that marked the long-awaited first phase of the Trump Middle East peace plan unveiled a $50 billion aid package to the Palestinians, Jordan, Lebanon, and Egypt. The conference had come under substantial advance criticism in the Arab world, especially among Palestinians, with many declaring it a failure from the start.

In the aftermath, there certainly is a sense of a missed opportunity. The conference failed to secure funds from the oil-rich Gulf Arab countries or win over the Palestinians and their neighbors. The main sticking point for many was the lack of discussion so far of a political solution. Senior Trump adviser Jared Kushner admitted in Bahrain that “this is a very executable plan if we are able to get a political solution.”

But the White House has insisted on a media blackout to prevent “spoilers” from undermining the plan. So diplomats are all working from a trail of hints, leaks, and speculations as to what the plan may be. Read the full version for answers to five questions, including whether the conference brought Arabs and Israelis any closer to peace, and where the Palestinians go from here.

Money first, politics later. Did Bahrain advance Mideast peace?

At the Bahrain conference that marked the long-awaited first phase of the Trump Middle East peace plan, senior adviser Jared Kushner and White House envoy Jason Greenblatt unveiled a detailed $50 billion aid package to the Palestinians, Jordan, Lebanon, and Egypt.

Among the initiatives: a road and rail corridor between Gaza and the West Bank, regional desalination and energy projects, international investment, and easing borders to integrate the West Bank and Gaza into the global market.

But the conference had come under substantial advance criticism in the Arab world, especially among Palestinians, with many declaring it a failure from the start. One week later, what do we know?

Was there progress, or was it a missed opportunity?

There certainly is a sense in Washington and in European and Arab capitals of a missed opportunity.

The conference failed to secure funds from the oil-rich Gulf Arab countries or win over the Palestinians and their neighbors, leaving many to wonder whether the last two years of political pressure and posturing could have been better spent achieving progress on both the economic and political fronts.

“There is nothing wrong with the ideas. They are wonderful. [Secretary of State John] Kerry and [President Barack] Obama embraced them before,” says Hady Amr, who served as deputy special envoy for Israeli-Palestinian negotiations, specializing in economic issues, under the Obama administration.

“What is new is that they refused to discuss sovereignty and two states. The Palestinians are not interested in a discussion about economic growth unless it is side by side with a conversation on freedoms and sovereignty.”

Without a discussion on a political settlement allowing for Palestinian self-determination and free movement of goods and people, the proposals fell flat. Adding to this was the fact that no Palestinian or Israeli officials were present; only a handful of Palestinian businessmen came.

“There was never even an opportunity,” says Mr. Amr. “You don’t have a conference on a topic if those people won’t talk to you.”

Bahrain was economics. What is the political plan?

Good question. Mr. Kushner admitted at Bahrain that “this is a very executable plan if we are able to get a political solution.” The White House says it will unveil this solution toward the end of this year, insisting on a media blackout to guard against “spoilers” bent on undermining the plan.

Diplomats in Brussels, London, the State Department, and the foreign-policy establishment in Washington all say they are in the dark. Instead, they work from a trail of hints, leaks, and speculations as to what the plan may be.

These include Mr. Kushner’s stated doubts about a two-state solution, Mr. Trump’s relocation of the U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem and recognizing it as the capital of Israel, shutting the Palestinian Authority consulate in Washington, and cutting funds to the Palestinian territories and the refugee organization UNRWA. This has led many to conclude that the plan will call for semi-autonomous cantons in parts of the West Bank and Gaza, short of a state.

On Wednesday, speaking to reporters, Mr. Kushner hinted that the plan would also promote settling Palestinian refugees in host Arab countries rather than grant them a right to return to ancestral lands in Israel, suggesting that the U.S. again would come down on the Israeli side of a hotly disputed point. He said the U.S. would announce next steps as soon as next week.

“I think it is clear that whatever the political solution is, it will be short of an independent state for Palestinians and will make Jordan and Egypt step in to carry the security responsibilities currently held by the Israelis in return,” one European diplomat in the region said.

Are Israelis on board with what the U.S. is offering?

It depends on the offer and what emerges from Israel’s political paralysis in September’s repeat elections. Israelis broadly support economic development in the Palestinian territories, believing it contributes to regional stability and Israeli security. “Economic Peace” is a core concept pushed by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu since 2008.

But the devil, and the difficulties, are in the details. Linking the Gaza Strip and the West Bank by railway and roads, a core tenet of the Kushner plan, is seen by Israel as a security threat due to the militant Hamas’ control of the Strip.

“I don’t know if it is possible to connect the West Bank and Gaza though rail and roads. As long as Hamas controls Gaza, it is just not going to happen,” says Gen. Michael Herzog, a veteran Israeli negotiator and fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

“It would be very hard for any Israeli PM to say no, but if the plan happens to touch core Israeli interests such as security, it might be the case that Israel does not go along.”

Are Arabs and Israelis closer to peace?

Arabs and Israelis met together publicly in the Gulf for the first time, and it certainly looks very positive: Israeli businessmen chatting up Emirati and Saudi investors; Israeli and American delegates praying in a historic synagogue in Manama. This week, Israeli Foreign Minister Israel Katz visited Abu Dhabi, while Israel announced it will open a representative office in Oman. Mr. Katz was the most senior Israeli minister to publicly visit a Gulf Arab country, but these steps forward do not necessarily mean full ties between Arab states and Israel are imminent.

High-level Israeli visits to the Gulf have occurred on a semi-frequent basis over the last decade unpublicized. But Gulf officials’ enthusiasm is tempered by popular opposition to normalizing ties among Arab publics, politicians, and even royals who demand the establishment of a Palestinian state as a precondition to Arab-Israeli peace. Kuwait, Lebanon, and Iraq boycotted the Bahrain conference.

Jordan and Egypt, the only two Arab states with peace treaties with Israel, sent low-level delegations to Bahrain due to public opposition at home, while Morocco sent a ministry employee. Activists at the “Bahrain Society Against Normalization with the Zionist Enemy” publicly mopped the spot where an Israeli delegate took a selfie outside its Manama headquarters to “cleanse” the building. All this underlines the urgent need for a political solution between Israel and the Palestinians in order for peace with Arab states to follow.

“Gulf states want to move ahead, but they have restraints in the public opinion and cannot rush ahead with normalizing ties with Israel as long as there is no progress on Palestinian-Israeli issues,” General Herzog, the veteran Israeli negotiator, says.

Where do the Palestinians go from here?

After boycotting the Bahrain conference in the face of considerable pressure from Washington, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, Palestinian leaders have emerged like bloodied victors of a marathon prize fight. They have undermined the legitimacy of the Trump peace process, damaged the Gulf’s credibility as brokers, and limited Arab participation by playing up the emotive issue of Palestinian statehood and victimhood. But they hold no other cards.

Palestinian officials say privately they plan to “run down the clock” on the Trump administration, boycotting, obstructing, and protesting the White House’s statements and diplomacy until either the inhabitant of the White House changes or the president becomes distracted with an international or domestic crisis.

But obstructionism will not make their problems go away. Gaza is home to the highest unemployment rate in the world at 52%; the West Bank’s hovers at 19%. The Palestinian Authority is deeply unpopular in the West Bank, while Hamas is facing its own domestic opposition with crackdowns. Corruption is rampant. Gaza is one step away from another conflict, and the West Bank remains dependent on international aid. Passing up the billions at Bahrain looks like a steep price to pay, but for now, Palestinians say it is worth it.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this story mischaracterized the precedent of an Israeli minister’s visit to the Emirates.

A deeper look

Why Queens is the ‘Noah’s ark of languages’

The loss of a single language, legendary linguist Kenneth Hale used to say, “is like dropping a bomb on the Louvre.” Saving the world’s rarest words means travel – hopping a subway to Queens.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

To stand out in New York City, all Alex Paz has to do is open his mouth.

The Queens resident is one of only a handful of people who speaks P’urhépecha, an indigenous pre-Columbian language spoken in southern Mexico. P’urhépecha is not only rare, but also one of a kind, linguistically unrelated to any other known language.

“There are things that can only be said in my language,” says Mr. Paz, who’s been working with linguists to preserve P’urhépecha.

Mr. Paz lives in the most linguistically diverse neighborhood on earth. With as many as 800 distinct languages spoken throughout this sprawling borough, Queens has a diversity of tongues and dialects unprecedented in human history.

Linguists estimate that up to half of the 7,000 languages spoken today are likely to die off by the end of this century. Most will succumb to the homogenizing effects of global capitalism and digital media, as well as the efforts of leaders who believe a single national tongue will strengthen cultural cohesion. It’s not simply nostalgia that motivates efforts to preserve the world’s dying languages, linguists say: Every spoken tongue is rich with the experiences of humanity.

Queens is the perfect place to pursue preservation efforts. “This neighborhood in particular is like, I would say, the Noah’s Ark of languages,” says Daniel Kaufman, executive director of the Endangered Language Alliance.

Why Queens is the ‘Noah’s ark of languages’

Like many immigrants who live near the busy subway hub in Jackson Heights, Tenzin Namdol usually talks to her family and friends with a shape-shifting array of tongues.

She’ll jump from colloquial Tibetan to standard English in the middle of a conversation almost without a thought, and then start speaking what she says has become a third hybrid of slang, combining the phonetics of both. She also speaks fluent Hindi, the language she prefers when hanging out in one of her Queens neighborhood’s famed local restaurants or one-of-a-kind shops.

Despite this easy fluency in a number of very different languages, Ms. Namdol becomes wistful when it comes to one she hasn’t quite mastered – the native tongue of her mother, whose people speak a rare Himalayan dialect called Mustangi.

There are only about 3,000 people left in the world who still speak Mustangi, and most live in a remote Himalayan region in western Nepal. But a few hundred or so of these speakers, including Ms. Namdol’s mother, now reside in the New York borough of Queens.

This also happens to be the most linguistically diverse neighborhood on earth, scholars say. With as many as 800 distinct languages, Queens has a diversity of tongues and dialects unprecedented in human history – and its epicenter is here amid the concentrated din of Jackson Heights.

Linguists estimate that up to half of the 7,000 languages spoken throughout the world today are likely to die off by the end of this century, most succumbing to a number of homogenizing forces in the modern world.

Global capitalism, digital media, as well as the long-standing political efforts of national leaders who’ve believed that a single, nation-binding tongue would only strengthen their country’s cultural cohesion and economic efficiency, are only a few of the reasons so many languages are disappearing today.

“Sadly, my mother didn’t pass down her language to me,” says Ms. Namdol, whose family lived among the Tibetan diaspora in Dharamshala, India, before emigrating to New York. “So it’s hard to really explain this right now, but it’s like, I feel I’m on the outskirts of my own community.”

In many ways, Ms. Namdol’s longings are part of a classic story of immigrants who come to New York. The city has long produced a literature of essays, memoirs, and novels written by new residents and first generation Americans who longed to find an elusive and self-grounding feeling of “home” – even as they chronicle the uneasy liberty America provides to put aside the past and invent the self anew.

Part of this classic story, too, has been the well-intended reactions of immigrant parents like her mother, who raised her daughter to speak the lingua franca of their wider community, the standard Tibetan used for commerce, government institutions, and the traditions of Buddhism. What use could a language like Mustangi offer her daughter?

“Now if I go to a gathering of my mother’s people, I’m not able to understand their words, so they don’t really identify me as one of their own because I don’t know their language,” says Ms. Namdol. “I want to feel connected. I want to sing with them. I want to dance with them. I want to share their stories and laugh with them. I can’t do that.”

Yet as she works through her ambivalent feelings about her “hybrid” identity, an identity particular to this sumptuous diversity of Queens, the recent college grad decided to join a wider-ranging effort to document and preserve the growing number of languages about to become extinct throughout the world.

For the past year, she has begun to learn the words of Mustangi, volunteering with the Endangered Language Alliance, a nonprofit in Manhattan that works with immigrant communities to preserve their dying languages.

Collecting the stories of local Tibetans in their native tongues, she’s been recording them for the alliance’s project “Voices of the Himalayas,” learning more about some of the other seven languages spoken in Jackson Heights’ Tibetan diaspora, including her father’s native tongue, Kyirong, a three-tone Tibetic language spoken mostly in Nepal.

‘Babel in reverse’

Jackson Heights is the perfect place to pursue such preservation efforts. Over the past decade, in fact, linguistics scholars have begun to focus more of their research on such urban immigrant communities, where in many cases there are more speakers of a rare language than in the region where it first evolved.

“This neighborhood in particular is like, I would say, the Noah’s Ark of languages,” says Daniel Kaufman, a professor of linguistics at Queens College and the executive director of the Endangered Language Alliance. Others have used another metaphor from Hebrew Scripture, calling New York “Babel in reverse,” its towers, in effect, acting as magnets for language diversity.

“We linguists talk about places like New Guinea and Vanuatu and Indonesia as having this incredible language density, a density that evolved naturally through a kind of linguistic ‘speciation,’” says Dr. Kaufman, who also heads Queens College’s new Language Documentation Lab. “But this area here came about through immigration.”

And it’s really just a coincidence, Dr. Kaufman says, that Jackson Heights happens to be at the crossroads of language diversity. The immigrant communities clustered here happen to be from countries that already have the most spoken languages in the world, including India, Nepal, the Philippines, and Mexico. Each of these countries has hundreds of indigenous communities that speak their own language.

There are also a number of rare European languages in pockets of Queens. In Astoria, a number of people still speak Vlaski, a Croatian-Istrian tongue that sprang from nomadic shepherds who settled in the Balkans in the 16th century. Most of the world’s remaining speakers of Gottscheer, a Germanic dialect in what is now Slovenia, reside in nearby Ridgewood. Bukhari, the language spoken by Jewish immigrants from Uzbekistan, has more speakers in Queens than in the old countries.

‘The essence of who we are’

Alex Paz, however, may be one of only a handful of people living in New York who speaks P'urhépecha, an indigenous pre-Columbian language spoken in southern Mexico.

Considered an “isolate” among human tongues, P'urhépecha is not only rare, but also one of a kind, linguistically unrelated to any other known language in the world.

“There are things that can only be said in my language,” says Mr. Paz, an immigrant from the small mountain town of Ocumícho in the Michoacán region of southern Mexico. “Even at home, I can see how my language is disappearing, and this means a lot of cultural aspects, too, because language – once we lose our language, I think that’s the essence of who we are.”

P'urhépecha is one of the 68 national languages recognized by the Mexican government, yet linguists say there are actually more than 200 indigenous languages spoken throughout Mexico, making Mexico one of the most linguistically diverse countries in the world.

Today, Mr. Paz, too, has been volunteering for the Endangered Language Alliance, trying to locate and collect everything that’s been written in P'urhépecha over the past few decades. And while he hasn’t found anyone else in New York who speaks his language, Mr. Paz has been immersed in it as he never has before, putting what he finds into a database and then providing word-by-word translations into English and Spanish – a complex and complicated task, he says, since many of his language’s words contain concepts nearly impossible to translate.

Though only in his 20s, he worries that he may be among the last to learn his people’s ancient tongue. After his family emigrated to Pennsylvania 10 years ago, his little sisters haven’t learned P'urhépecha. He learned the language as a child by speaking to his grandmother, who doesn’t speak Spanish. But since she still lives in southern Mexico, they rarely get the chance to see or talk to their grandmother now.

But it’s not simply nostalgia or the immigrant longing for home, however, that motivates efforts to preserve the world’s dying languages, linguists say. Like the evolution of creatures, the complexity of human language virtually defines the species, and every spoken tongue is rich with the experiences of humanity.

“The loss of local languages and of the cultural systems which they express, has meant irretrievable loss of diverse and interesting intellectual wealth,” wrote the legendary linguist Kenneth Hale. “Only with diversity can it be guaranteed that all avenues of human intellectual progress will be traveled.”

The loss of any one language, he used to say, “is like dropping a bomb on the Louvre.” When a language goes extinct, in many cases thousands of years of accumulated human knowledge are lost. Every language has enormous reserves of cultural, ecological, and even botanical information considered vital for local communities.

“This idea that sets of experiences became words and languages is not really correct, as if we’re just kind of setting old experiences to a set of new words,” says Dr. Kaufman. “When people get into the revitalization of indigenous languages, it’s really that those words have their own special use and their own special contexts, that really you’ll only ever learn experientially.”

Yet the ever-branching tree of human language has long been replete with slowly changing hybrids and offshoots that often meet their linguistic end. And since hunter-gatherer times, violence and cultural dominance have been a major part of the evolution of languages. Modern English, in fact, began to form after the invasion of William the Conqueror in 1066, and the subsequent cultural domination of French speakers in Anglo-Saxon lands.

Similarly, centuries of colonialism and myriads of nationalist projects in countries around the world during the 20th century created an active process of linguistic suppression and even elimination.

These external forces then gave rise to the more subtle internal forces that Ms. Namdol and Mr. Paz both know well: shame.

Even in the Tibetan communities in Nepal, there is a hierarchy of value attached to its many tongues. “We speak the Lhasa dialect, the standard Tibetan language, part of Buddhist religion, and if you speak Lhasa, then you are respected. Others are what you would call, I’d say, a village language,” says Ms. Namdol.

‘She wanted me to become my own person’

On the one hand, older Mustangi women often assert their generational identity by cluck-clucking the ways of the young, decrying what’s being lost in their culture. They tend to shame Ms. Namdol, however subtly, as an outsider. Yet at the same time, her mother made a conscious decision not to teach her daughter the language of her ancestors.

“There were a lot of layers to this, and from her perspective, she’s right,” Ms. Namdol says. “She didn’t want me to deal with a lot of the caste system that was involved in the society of Nepal itself, or even in India. So she wanted me to become my own person, separate from my own community.”

“But now we’re living in the generational world. We have to live in a cultural setting, and at the same time we have to adapt to the newer, modern world,” she continues. “But then we also have to stay grounded, while we have that pressure to stick with our culture and everything. Yet from a language perspective, we have a lot of people, the next generation, I would say, most of them, they don’t even speak Tibetan now.”

Mexico has made a lot of efforts to preserve its linguistic diversity over the past few decades, but Mr. Paz laments the educational policies that emphasize Spanish, and the similar kinds of shaming and intracultural racism when it comes to the country’s array of indigenous people and the marginalization they often feel.

“It’s like the language is the only thing that we have left, and its concepts,” Mr. Paz says. “I don’t want to read somewhere, or have to say, ‘Back in the day in Michoacán we used to speak this language, P'urhépecha.’ It’s sad, and I want to at least try to keep it alive, and to keep it real.”

Trying to change Congress, starting with the lowest rung: interns

Most Capitol Hill internships are unpaid, making them out of reach for many aspiring public servants. The nonprofit College to Congress is trying to change that – and bring socioeconomic diversity to the halls of Congress.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Interns are key cogs in the machinery of Washington. About 8,000 arrive in the city every year. On Capitol Hill, particularly during the summer, they can be found doing everything from answering constituent calls and opening mail to conducting policy research. Most congressional staffers get their start as interns.

For years, however, these posts were largely out of reach to all but the wealthy and well-connected. The vast majority of internships here are unpaid, in a city where the median rent for a two-bedroom apartment is about $1,570.

The organization College to Congress is trying to change that. The nonprofit, now in its fourth year, helps low-income students secure congressional internships and covers their housing, food, clothing, and transportation needs.

The goal is to open up the Hill’s staffing pipeline to more than just those who can afford to work for free, says Audrey Henson, who started the program.

She hopes to address one of Congress’ most long-standing problems: a lack of diversity – not only in race and gender, but also in socioeconomic status. “We’re not just trying to change [a] student’s life,” she says. “We’re trying to change Congress.”

Trying to change Congress, starting with the lowest rung: interns

Ana Aldazabal nearly missed the vote.

She’d rushed to the gallery in the House of Representatives just as members were preparing to vote on HR 6, the American Dream and Promise Act of 2019. She watched as the bill – which would provide a path to citizenship for young immigrants like her – passed, 237-187.

For Ms. Aldazabal, it was a powerful moment. Not only because she’d waited almost her entire life for a bill like this, but also because she watched it all happen from a seat on the inside, as an intern for California Rep. Gil Cisneros.

“I was like, ‘Wow. I’m really here, as an undocumented immigrant in the most powerful city in the world, walking through the hallways that presidents have walked through,’” she recalls from a coffee shop at Union Station about a week later.

A Capitol Hill internship once seemed an improbable dream to Ms. Aldazabal, who grew up in La Habra, California. She had the qualifications – she’d been on the dean’s honor list and president of the university student union when she graduated from Cal State Fullerton in May.

But she had assumed there was no way she could afford a summer in Washington. Most Hill internships are unpaid, and interns here often work part-time jobs or take out loans to make ends meet. Her family came to the United States from Peru without immigration documents, so Ms. Aldazabal didn’t have those options.

The only reason she made it to Washington, she says, is because of College to Congress, a nonprofit that helps low-income students secure internships on the Hill. The program covers their food, housing, clothing, and transportation needs, and offers leadership and networking training throughout the summer.

The goal is to open up the Hill’s staffing pipeline to more than just those who can afford to work for free, says Audrey Henson, who started the program in 2016. Raised by a single mother in St. Petersburg, Florida, Ms. Henson lived off loans when she first came to Washington to intern on the Hill. She understands the challenge of being asked to split a bill with co-workers when you ordered only tap water on purpose, or trying to look professional every day when you own just one dress.

More broadly, Ms. Henson hopes to address one of Congress’ most long-standing problems: a lack of diversity – not just in race and gender, she says, but also in socioeconomic status.

“We’re not just trying to change [a] student’s life,” she says. “We’re trying to change Congress.”

Key cogs in the D.C. machinery

Interns are key cogs in the machinery of Washington. About 8,000 of them arrive in the city every year, according to the Congressional Management Foundation. On Capitol Hill, they’re tasked with everything from answering constituent calls and opening mail to conducting policy research. Most congressional staffers get their start as interns, and many more who end up working in nonprofits or lobbying firms also put in time on the Hill.

A 2017 survey by the advocacy group Pay Our Interns found that about 90% of House interns served unpaid. At the same time, the cost of living in Washington has soared. As of June, the median rent for a two-bedroom apartment in the city is about $1,570. Add to that the cost of meals, the Metro, and networking over drinks and coffee – a very real part of what it takes to succeed – and it’s no wonder students like Ms. Aldazabal see internships as out of reach.

“My family is not in the financial position to just be like, ‘Here’s $5,000 to go and train in Congress,’” she says.

College to Congress fills the gap with an investment of about $10,000 in each of its students over the course of a summer. The funding covers airfare to and from Washington, a room in an apartment near the Capitol, three meals a day, a clothing allowance, a Metro card, and, as of this year, $300 in Lyft credits for the 2 1/2 months the interns are in town.

When Jay Cho first heard about the program – particularly the clothing stipend – he found himself thinking about his old suit.

Mr. Cho, who spent more than four years as a congressional staffer before going corporate in 2018, still keeps as a memento the one polyester suit he wore to his Hill internships when he was in college. His parents didn’t have the money to get him through four years at American University, so he lived on a mix of grants, loans, and the wages he earned working at the pizzeria beside campus. Now a member of College to Congress’ corporate leadership council, Mr. Cho says he often walked the 6 miles from school to Capitol Hill to save on bus and Metro fare. His suit, stapled together in places to keep it from falling apart, would set off the metal detectors at the Cannon House Office Building.

“A lot of people [on the Hill] do not have any idea what it’s like not to have any money, what it’s like to see that $6 balance in your bank account,” says Mr. Cho in a phone interview. “These are the people doing the work to create programs that help low-income students and families. When these discussions are happening, I want there to be someone in the room who knows what it’s like.”

Intern boot camp

Once they land in D.C., students are whisked into an intensive weekend boot camp, where they learn both the nitty-gritty of congressional office work and the soft skills – like networking and time management – that are vital to success in Washington.

The program is explicitly bipartisan. Ms. Henson’s own politics lean Republican – she interned for former Rep. Joe Barton of Texas and current Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida before becoming a staffer for Rep. Bill Johnson of Ohio. And College to Congress interns are chosen with an eye to diversity in ideology and experience, in addition to race, culture, and gender. The program says Ms. Aldazabal, who landed a spot at a freshman Democrat’s office, is its first undocumented intern. But her peers in the program include a pair of military veterans (working for Republican offices), several first-generation college students (from both sides of the aisle), and a survivor of a school shooting (also Republican).

Each student is paired with a Hill staffer from the opposite party who serves as a mentor throughout the summer.

“Everything on Capitol Hill is built around relationships,” Ms. Henson says. “If you only meet your opponent on the House floor when you’re yelling at each other ... then you’re never having that chance to build camaraderie, to build friendship, to look for areas to work together.”

Still, there’s only so much one nonprofit, even combined with others, can do. The reality is that Washington is expensive, and the cost of living remains a major barrier for many talented young people across the country with dreams of working in public service.

Lately, Congress – in the face of much lobbying and shaming – has begun to recognize that fact. Last year, it approved $14 million in internship funding that became available to member offices in March. Each House office now has $20,000 to spend on interns, while Senate office funding is broken down according to state size.

For Ms. Aldazabal, her immigration status means she can’t go on to work in government, but she’s looking at nonprofits, maybe law school – somewhere she can combine her newfound knowledge of the legislative system with her interest in immigration policy.

Right now, she’s just thankful for the opportunity College to Congress is providing.

“It’s one thing to ask for diversity in Congress, but it’s another to actually do the work,” says Ms. Aldazabal. “The program is ... revolutionary.”

A visit to Korea’s DMZ: Fast food, a pirate ship – and a bit of hope

The 155-mile-long Demilitarized Zone that divides South and North Korea contains its share of the absurd and the solemn. It also holds reason for hope that one day, it won’t be needed.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

From Seoul, South Korea’s teeming, tech-savvy capital, North Korea seems as remote as the moon.

But it’s actually just 30 miles to the Demilitarized Zone, the barrier dividing North and South. As Monitor correspondent Martin Kuz set off to visit the DMZ, he imagined barbed-wire views and a grim perspective on war.

Instead, he discovered, the reality could have been titled “Universal Studios Presents: The DMZ!” – even before last week’s geopolitical fever dream of a sitting U.S. president setting foot in North Korea.

In truth, the meeting between President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un reflected the day-to-day blend of absurdity and solemnity that awaits tourists drawn to the DMZ. Between the pirate ship ride, Popeyes fried chicken, and the “infiltration tunnel,” they might discover something even more unexpected: a sense of hope.

A short film for tourists declares that, until reunification, “The DMZ will be alive forever!” But the final tour stop contradicts that fatalism: a dormant train station connecting the Koreas. One sign points the way to Unification Platform. Above locked doors, another reads “To Pyeongyang.”

For now, it is the last station in the south. One day, it may be the first station to the north.

A visit to Korea’s DMZ: Fast food, a pirate ship – and a bit of hope

The Super Viking pirate ship surprised me. So did the Popeyes fried chicken, the soldier mannequins, and the DMZ action flick.

I had imagined that a trip to the Demilitarized Zone, the 155-mile-long barrier dividing South and North Korea, would provide only barbed-wire views and a grim perspective on the cruelties of war. The reality instead could have been titled “Universal Studios Presents: The DMZ!” And I visited a month before last week’s geopolitical fever dream that saw a sitting U.S. president set foot in North Korea for the first time.

In truth, the meeting between President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un reflected the day-to-day blend of absurdity and solemnity that awaits the 1.2 million tourists drawn to the DMZ each year. Between the amusement park and the “infiltration tunnel,” they might also discover something even more unexpected: a sense of hope.

I traveled with a group of U.S. journalists to the border zone from Seoul, South Korea’s teeming, tech-savvy capital, where North Korea seems as remote as the moon. Our shuttle bus skirted the wall and guard towers that demarcate the DMZ’s southern edge before reaching Imjingak, a park dedicated to the Korean War and its enduring fallout. The collision of contrasts began.

We joined the stream of visitors pouring out of tour buses and climbed up to a viewing platform. The deep-fried aroma wafting upward from Popeyes mingled in the morning air with the squeals of children riding the Super Viking, the main attraction of Peace Land, a theme park down the hill. In the opposite direction, the so-called Freedom Bridge stretched to the north across the Imjin River.

Some 13,000 prisoners of war returned to the South here in 1953, after the signing of an armistice established the DMZ and two Koreas. A chain-link fence blocks the entrance, and visitors have adorned the barricade with colorful ribbons and small flags depicting the Korean Peninsula that bear handwritten messages. Most plead for peace or express yearning for family beyond the border.

We stepped back on the bus and rode past Daeseong-dong, or Freedom Village. The lone South Korean town within the DMZ is home to 200 residents and a 323-foot-tall mast topped with the nation’s flag. A mile away, a North Korean flag rises 200 feet higher above Kijong-dong, or Peace Village, the North’s retort to its neighbor. South Koreans refer to the apparently empty enclave as Propaganda Village, with its brightly painted buildings and tidy lawns at odds with the North’s prevailing poverty.

The dueling flags waved in the breeze as we gazed through telescopes across the 2.5-mile-wide border zone from the Dora Observatory. The lack of human activity for more than 60 years has turned the DMZ into an accidental nature reserve. Black bears, musk deer, cranes, and dozens of other species flourish here – as long as they avoid the 800,000 land mines.

The lush landscape further obscures that the DMZ delineates an unmarked mass grave. Below the surface lie the remains of an estimated 10,000 South Korean soldiers and 2,000 U.S. troops, along with an unknown number of North Korean personnel.

The sleek, silver observatory opened last fall, replacing its former confines, a Brutalist-style blockhouse painted camouflage. But it was the slogan on the old building’s facade – “End of Separation, Beginning of Unification” – that trailed me to our next stop, where we hunch-walked down the “3rd infiltration tunnel.”

Three concrete barriers block the center of the tunnel, one of four entering from the north that the South Korean military has discovered. A small window cut into the third barrier offers a glimpse of the second. Until the past year, I thought, the dark space between them could have served as a tomb for the prospects of peace.

Mr. Trump and Mr. Kim, encouraged by South Korean President Moon Jae-in, had met twice to discuss ending North Korea’s nuclear weapons program before their “handshake summit” last week in the Joint Security Area of the DMZ. Meanwhile, talks between the two Korean leaders have brought gradual changes in relations between their countries, including the razing of 10 guard towers on each side of the border and a ban on weapons in the security area. The small steps, if criticized as largely symbolic, represent the most progress toward detente in a decade.

We had learned earlier that the security area was closed, so our only brush with poker-faced guards occurred outside the tunnel entrance. There, a pair of South Korean soldier mannequins stood in requisite sunglasses and requisite taekwondo stance – arms stiff at their sides, hands balled into fists – as they posed without complaint for photo after photo.

A few steps away, a gift shop stocked an array of DMZ-themed items, ranging from T-shirts and baseball caps to keychains, fridge magnets, and car air fresheners. Pieces of “authentic” barbed wire from the border fence, neatly mounted on plaques, suggested an entrepreneur’s cynical flair for monetizing conflict.

Tchotchkes in hand, we walked outside toward a small movie theater, passing by a set of large D-M-Z letters that visitors hugged as if greeting old friends. We watched a short film on the Korean War and the border zone that resembled an extended trailer for a summer blockbuster, complete with simulated on-screen explosions and WrestleMania voice-over. As the video concluded, the narration reached a crescendo, reassuring us that until the day of reunification, “The DMZ will be alive forever!”

Our final tour destination contradicted that fatalism. The Dorasan train station opened in 2002 near the DMZ’s southern boundary. A rail line runs into North Korea, but since a spurt of freight traffic a decade ago, the route has remained dormant.

The station, bright and clean, includes an area for customs processing, an electronic timetable, and an arrow pointing the way to Unification Platform. Above the locked doors leading to the tracks, another sign reads “To Pyeongyang.”

For now, it is the last station in the south. One day, it may be the first station to the north.

Reporting for this story was made possible by a travel fellowship provided through the East-West Center.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

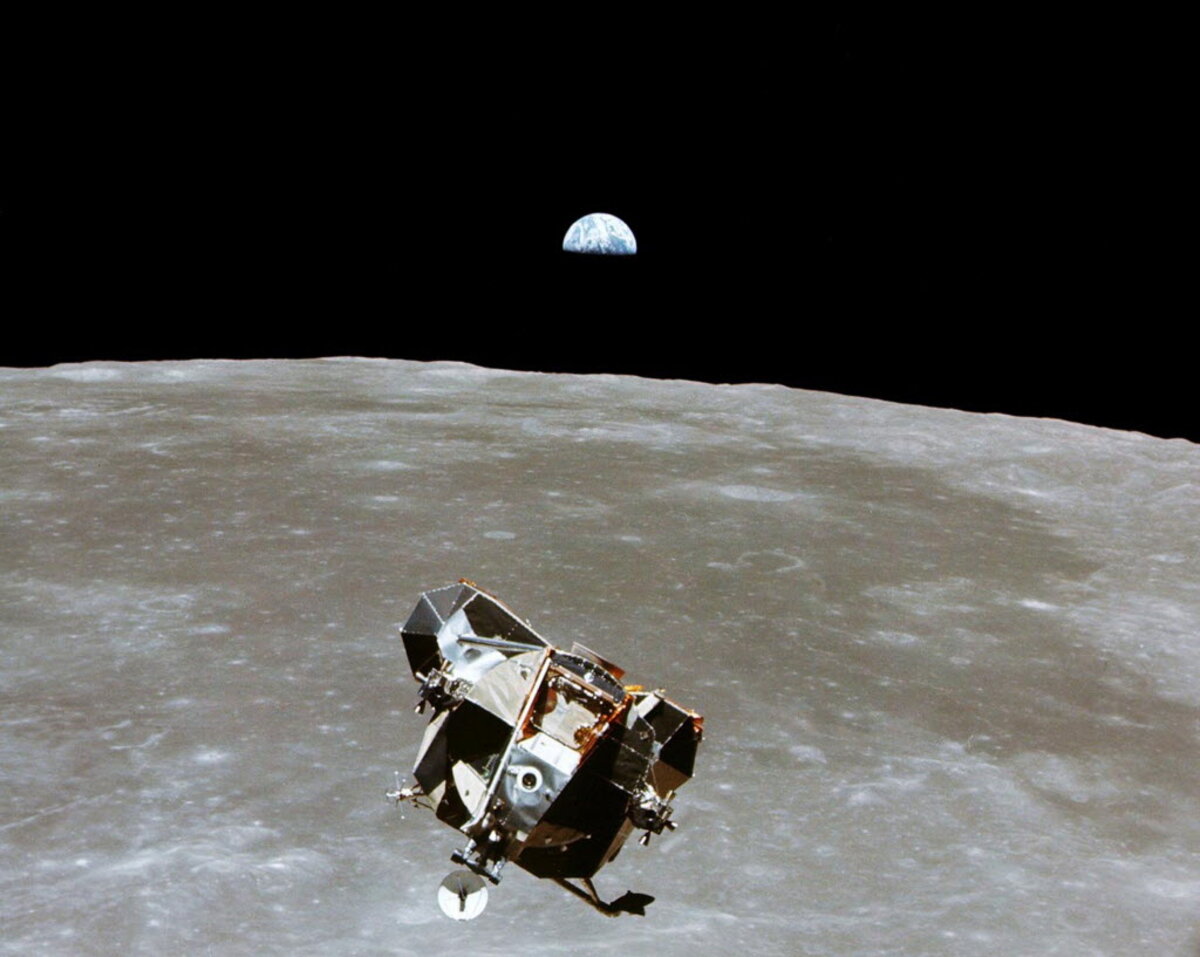

50 years on, why the moon landing still inspires

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

From the moment of the moon landing in 1969, history became divided into “before” and “after” the first visit to another celestial body by humans. The landing was not just a boost to human confidence or new physical comforts. “I want my children ... to see a country that stands for something more than just consumption,” said former NASA administrator Daniel Goldin.

The globally televised event was a transcendent moment that reflected an unmet need to know and understand creation. “I do believe that there is a deficiency in the American spiritual diet which space exploration can help us remedy,” noted American historian Daniel Boorstin. That ongoing “diet” is represented in the name of a NASA rover on Mars since 2012: Curiosity.

The world of 2019 presents no lack of problems on Earth. Yet solutions now seem easier because that landing by the Apollo 11 astronauts keeps reminding us that when motives are lifted up, the limits in the human experience are left behind, too.

50 years on, why the moon landing still inspires

The new movie “Yesterday” imagines what the world would have missed if the Beatles had never existed. A similar question might be asked about what life would be like today if, in July 1969 as the Fab Four were recording “Abbey Road,” three American astronauts had not landed on the moon.

From the moment they did land, history became divided into “before” and “after” the first visit to another celestial body by humans.

A half-century later, another compelling question is this: What if Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin had not safely made it to the lunar surface or had failed to return their Eagle spacecraft to the orbiting command module and Michael Collins? Earlier missions had vividly demonstrated the dangers of space exploration. As in any great discovery, expecting the unexpected is the norm. And fear is only one more obstacle to conquer.

In the turbulent times of the 1960s, one common question was this: “Why spend so much money on NASA at a time of war and social unrest?” Why look to the stars when so many suffer on Earth?

An answer to that question came in a call by President Richard Nixon to the astronauts as they left their bootprints on the Sea of Tranquillity. “Because of what you have done, the heavens have become a part of man’s world,” he said, and “it inspires us to redouble our efforts to bring peace and tranquillity to Earth.”

New tools for human tranquillity were indeed a NASA spinoff. Writer Norman Mailer wrote that the project set engineers and computer programmers to dream “of ways to attack the problems of society as well as they had attacked the problems of putting men on the moon.”

The landing was not just a boost to human confidence or new physical comforts. “I want my children ... to see a country that stands for something more than just consumption,” said former NASA administrator Daniel Goldin.

The globally televised event was a transcendent moment that reflected an unmet need to know and understand creation. “I do believe that there is a deficiency in the American spiritual diet which space exploration can help us remedy,” noted American historian Daniel Boorstin. That ongoing “diet” is represented in the name of a NASA rover on Mars since 2012: Curiosity.

Religious texts have long expressed the human wonder about creation and the eagerness to understand it. “When I consider thy heavens, the work of thy fingers, the moon and the stars, which thou hast ordained; What is man, that thou art mindful of him?” the Bible’s psalmist asked, and then concluded, “Thou madest him to have dominion over the works of thy hands; thou hast put all things under his feet” (Psalms 8:3-6).

A recent Gallup poll found 91% of Americans said they were proud of the country’s scientific achievements, a higher percentage than were proud of the military (89%) or economic achievements (75%). When thought soars, achievements follow. “The devotion of thought to an honest achievement makes the achievement possible,” the founder of The Christian Science Monitor, Mary Baker Eddy, wrote more than a century ago.

For Armstrong, the landing was only a beginning: “There are great ideas undiscovered, breakthroughs available to those who [search them out]. There are places to go beyond belief.”

The world of 2019 presents no lack of problems. Yet solutions now seem easier because that landing by the Apollo 11 astronauts keeps reminding us that when motives are lifted up, the limits in the human experience are left behind.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Claim freedom!

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Laura Bantly

“No need to feel forever trapped,” assures this poem, which highlights everyone’s God-given right to progress, safety, and strength.

Claim freedom!

No need to feel forever trapped

by years of wasted time

and effort brought to naught.

Shut out bleak images of

barren days gone by

and what they’ve left undone.

Your heritage is strength divine

to do the right,

reject the wrong.

Use that strength

to leave the wilderness

of doubt and fear behind.

Securely held in God’s embrace,

emerge from darkness into light.

He’ll tell you what you ought to do

and what you need to know.

Did you not know?

You’re one with Him!

The past is naught;

there is just now!

Safe with Father-Mother Love,

progress ever will unfold.

You are the child of God!

Claim freedom as your prize!

Originally published in the Oct. 8, 2018, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

A castle in ruins

A look ahead

Come back Monday. We’ll have a story about what to do when you love someone but hate their politics. Protect your close relationships in a partisan world.