- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Vaping rises as public health concern – especially for teens

Welcome to your Daily. Today we have stories addressing the relics of hate, an African leader’s complex legacy, one man’s alternative to violence, and rising women in both chess and tennis.

But first, one state governor this week took action on a topic of growing public concern. Gretchen Whitmer ordered an emergency ban on flavored electronic cigarettes, making Michigan the first state to take that step.

Two recent deaths in the U.S. have been linked to vaping. Federal and local officials are investigating a possible link to e-cigarettes in more than 200 reports of pulmonary disease from 25 states. In just the year from 2017 to 2018, the share of 12th graders who reported vaping in the past 30 days doubled, to 1 in every 5.

The surge in teenage use is fueled partly by companies pitching candy or fruit flavors that Governor Whitmer alleges aim to “hook children on nicotine.”

A ban is controversial. In this case it applies to adults as well as kids. It brings on a familiar debate over the boundaries between public health regulation and freedom of consumer choice. And the industry has blamed recent illnesses on illegal vaping pens that contain a marijuana-derived compound.

But some say the larger question behind this debate is how society will face up to the addiction risks of a product that’s often billed as safer than smoking. “Kids have such a poor understanding of vaping products – it’s extraordinary,” Michael Blaha, a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Maryland, said in a recent online post. “They’re not trying to quit smoking – they’ve never smoked before.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Fort Worth asks, Can a klan hall become a place of healing?

When it comes to relics of hate, what is the best way forward? In Fort Worth, some say to tear down an old Ku Klux Klan hall. Other Texans want to use it to honor victims of racial violence and promote healing.

The last purpose-built Ku Klux Klan building in the United States stands at 1012 North Main St. in Fort Worth, roughly a mile from where Fred Rouse was lynched in 1921.

The building’s future has sparked a passionate debate in the city that, a century later, is still rife with racial tension. The owner has applied to tear it down, but a group wants to convert it into a community space promoting dialogue, justice, and equity while honoring victims like Rouse. Some residents want it destroyed and others question whether transforming a building’s purpose can lead to wider transformation. But organizers believe that painful history needs to be examined to change the national narrative.

“This is an opportunity to hold that history to account, and to have the kinds of conversations here to make sure that that history is not repeated,” says Daniel Banks. “And to turn a monument of hate into a monument of memory and healing.”

Robert Rouse, grandson of Fred Rouse, still lives in Fort Worth and grew up listening to his father’s and grandmother’s stories. “The building at 1012 North Main was raised on nothing more than hate,” he said at a community meeting. “Let’s turn it into a flower.”

Fort Worth asks, Can a klan hall become a place of healing?

Two weeks before Christmas, in 1921, Fred Rouse was lying in a hospital bed, recovering from being beaten and stabbed by striking meatpacking workers.

Rouse was one of the black workers and immigrants hired to break the strike. He was leaving his shift when he was surrounded and threatened by striking workers, according to Fort Worth Star Telegram reports. Afraid for his life, Rouse shot and wounded two men before the crowd chased him down and beat him so badly police initially thought he was dead.

He had been in the hospital for five nights when about 30 white men came and took him from his hospital bed. He was found dead the next morning, riddled with bullets and hanging by a rope from a hackberry tree.

The hackberry tree was on Samuels Avenue about a mile from the Tarrant County courthouse, and about the same distance from a large meeting hall recently built by the Ku Klux Klan.

The tree is now gone, one of many relics of the past that modern, bustling Fort Worth has left behind. But the klan hall – believed to be the last purpose-built klan building in the United States – still stands at 1012 North Main St. The future of the building has sparked a passionate debate in the city that, a century later, is still rife with racial tension.

Adam McKinney, a dance professor at Texas Christian University, had been working on a piece about Fred Rouse this year when he learned that the owner of the building had applied for permission from the city to tear it down.

“Adam was actually dancing in front of the building” when he found out, recalls Daniel Banks, who with Mr. McKinney co-founded DNAWORKS, an arts and service organization, in 2006.

“So he’s dancing,” Dr. Banks continues, “and I’m sending tweets out tagging the mayor and tagging our councilwoman saying, ‘We have plans for this building. Would you like to hear them?’”

Their plan, still in its infancy, is to convert the former klan hall into a shared community space focused on promoting dialogue, justice, and equity in Fort Worth while highlighting the city’s history of racism and racial violence and honoring its victims. In July, a city commission voted to delay granting permission to demolish the building for 180 days.

“We are in an extraordinary time in history to get it right, and by ‘right’ I think I mean something about healing, and shifting our national narrative around race,” says Mr. McKinney. “The transformation of this building, this joint project, could be something transformational for us as a country.”

“Window dressing”

Public opinion over the building’s future runs the gamut, with the range of emotions felt most keenly in the African American community that makes up almost a fifth of the city.

Before the city commission vote in July, Raymond Brown – a Fort Worth resident for 55 years – stood up to give public comment. Wearing the jersey of football player and social justice advocate Colin Kaepernick, he told the room he had “mixed emotions.”

“I’m still on the fence,” he said. “To preserve it to me feels like the old Fort Worth way.”

Billy Daniels Jr. was the only commissioner to vote against granting the 180-day delay.

“Everything that stands doesn’t necessarily need to be preserved,” he said. “For us to leave this standing would be to perpetuate that racial problem that we have yet to really get a handle on.”

He was referring to a report released in December saying that racism in Forth Worth is “systemic, institutional, and structural.”

The report came from a special task force formed after a 2016 incident in which Jacqueline Craig, an African American woman, was arrested along with her two teenage daughters after she called police to report a neighbor grabbing her 8-year-old son’s neck.

Fort Worth also has seen the deaths of several unarmed black men at the hands of police, including Jermaine Darden during a 2013 raid and Christopher Lowe shortly after being taken into custody in 2018. The task force found evidence of systemic racial disparities: Despite constituting 19% of the population, African Americans accounted for 41% of arrests in 2016 and 2017; all 14 Fort Worth Independent School District schools classified as “Improvement Required” by the state were in minority neighborhoods; and racial segregation in the city, as measured by the federal dissimilarity index, increased between 2010 and 2018.

Outside a Starbucks in Montgomery Plaza, a historic department store converted into a shopping center and condominiums, Michael Bell is skeptical. A community activist since the mid-1980s, he doubts that converting the former klan hall into something devoted to healing race relations will make much difference.

“The real problem is as deep as the sidewalk,” he says. “Those attitudes have been crystallized – concretized, if you will – here in Fort Worth.”

As the pastor at Greater St. Stephen First Church since 1985, Dr. Bell has been in similar positions before. In the early 1990s he was part of the Tarrant Clergy for Inter-Ethnic Peace and Justice, a community group that received a local award “for improving and promoting positive human relations.” The group closed up shop a few years later.

“There’s always an effort which is window dressing. There’s always an effort to make it appear that there’s going to be some genuine [change],” he says. “But I’ve been living more than a minute now and I know better. My experience is that it’s not going to happen.”

“History would get lost”

The Fort Worth elite of the 1920s intertwined with the Ku Klux Klan. Texas and Indiana were the most active klan states in the country, and the group would parade hoodless down the city’s streets. Most of the sheriff’s and police departments were klan members, as was a co-founder of one of Fort Worth’s oldest law firms, according to Richard Selcer, a Fort Worth historian and author. Before they built the hall, the klan held meetings in the county courthouse basement.

Mr. Selcer says there were two lynchings in Fort Worth during this period: Rouse and Tom Vickery, a white man who killed a police officer. In both cases, klan members were implicated but the organization itself was not accused of anything.

By the late ’20s the klan was losing membership, influence, and funds. Two years after raising enough money to rebuild the hall after a fire (arson was never proved), the klan sold the building to a grocery. They had already been renting it out for public performances: Harry Houdini appeared there in 1924. Over the years its roots faded from public memory. What became known as the North Main Street Auditorium served at various times as a dance hall, wrestling venue, boxing arena, and – from 1946 until 2000 – a factory for the Ellis Pecan Co.

“The klan hall name is on it, and will never be erased, but it was other things besides a klan hall for many, many more years,” says Mr. Selcer. “I’d love to see it saved.”

That will, among other things, be an enormous financial ask. The building could cost more than $30 million to renovate, he estimates. The Fort Worth Military History Museum is also interested in moving into the building, but “to save a building with that kind of money, you’ve got to have some deep-pocketed individual or group who really wants to save it,” he adds.

What happens when the stay of demolition expires is unclear. Justin Light, an attorney who represented the building’s owner at the July commission meeting, said at the time that a 180-day delay “does not mean that on day 181 the building is going to come down.”

In the meantime, DNAWORKS will be meeting with local groups and individuals, fundraising, and refining its plan for the building. The stakes are high, the organization believes.

“The history of racism and slavery and Jim Crow and lynchings and racial terror, these stories aren’t told enough,” says Mr. McKinney. If the klan hall were torn down, he continues, “I feel like a history would get lost.”

“This is an opportunity to hold that history to account, and to have the kinds of conversations here to make sure that that history is not repeated,” adds Dr. Banks. “And to turn a monument of hate into a monument of memory and healing.”

Perhaps their most significant endorsement came at the July meeting, when Robert Rouse, the grandson of Fred Rouse, made his comments.

He grew up in Fort Worth hearing his father and grandmother tell stories “of what you could and couldn’t do.” You couldn’t drink from the white water fountains. You couldn’t go to certain parts of Leonard’s Department Store. You couldn’t, like his grandfather, try to work at a meatpacking plant.

“The building at 1012 North Main was raised on nothing more than hate,” he said. “Let’s turn it into a flower.”

Liberator or oppressor? For many, Robert Mugabe was both.

For many Western observers, the name Robert Mugabe brings to mind images of brutal control and economic chaos. But for many Zimbabweans, Mr. Mugabe’s legacy is far more complex.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Mxolisi Ncube Contributor

For many in Zimbabwe and abroad, Robert Mugabe was always far more than a president. Like Nelson Mandela or Fidel Castro, he seemed a country personified – in both its brightest days and its most troubled.

By the time of his death Friday, Mr. Mugabe’s failings were long established, from “land reforms” that sent images of weeping, bloodied white farmers around the globe to Zimbabwe’s eventual economic collapse.

Yet, for many, he remains an icon among African leaders. His 37-year reign began with a surge of hope. In the first decade of Zimbabwe’s independence, the country’s rates of infant mortality and malnutrition plummeted, while literacy and life expectancy shot up.

But soon many of his supporters turned into political rivals, as they began to suspect that his revolutionary ideals were at times a mask for a deep and unrelenting paranoia. And he eventually fell from power in a coup led by his former vice president, Emmerson Mnangagwa, in November 2017. But the effects of Mr. Mugabe’s rule will likely be felt in Zimbabwe for a long time to come.

Liberator or oppressor? For many, Robert Mugabe was both.

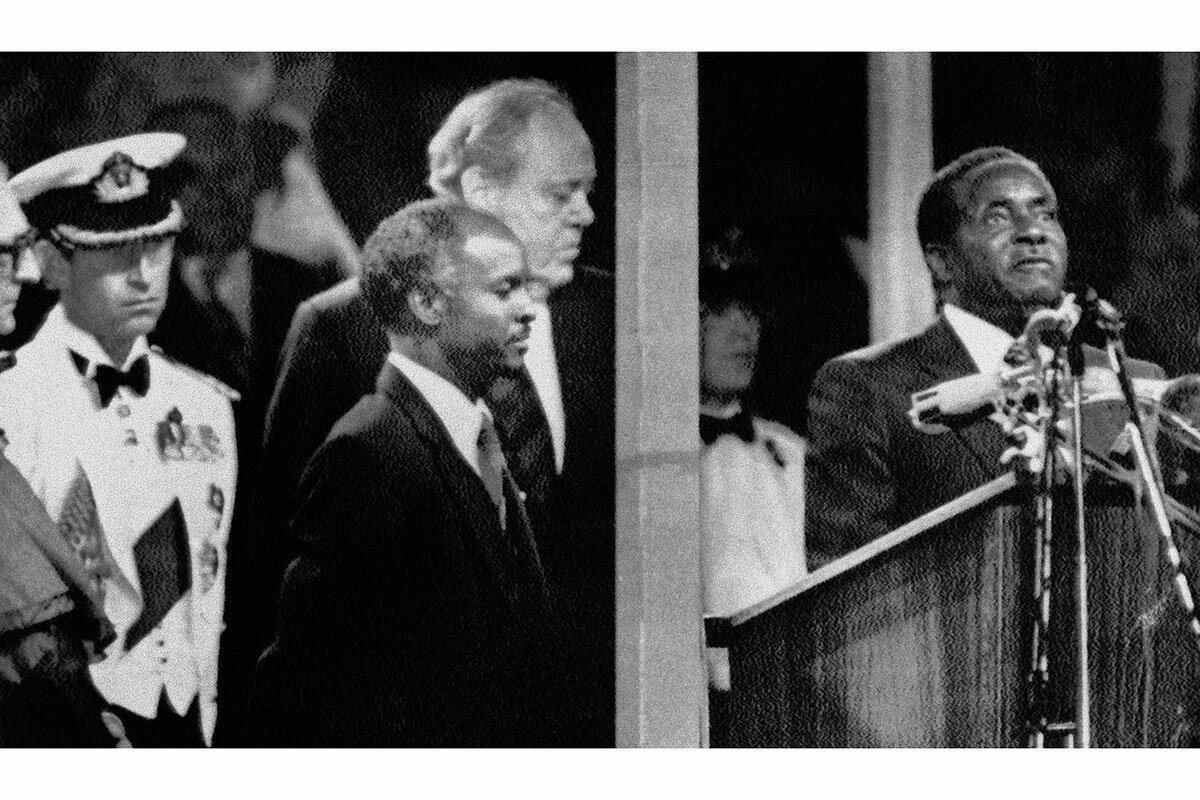

It was just after midnight on April 18, 1980, when a soccer stadium in the Zimbabwean capital, Harare, became the scene of one of the most improbable moments in modern African history.

As foreign dignitaries looked on and millions followed along on television, a cadre of white soldiers dressed in the scarlet uniforms of the colonial government marched lockstep with the camouflage-clad guerrilla fighters they had spent more than a decade locked in a brutal civil war against. Then the two groups stopped, pivoted, and in unison saluted the flag of their newly independent black nation.

“If yesterday you hated me, today you cannot avoid the love that binds you to me and me to you,” promised the prime minister of the minutes-old country, a bespectacled intellectual and former guerrilla leader named Robert Mugabe. “Oppression and racism are inequities that must never again find scope in our political and social system.”

For observers around the world, it seemed the beginning of a new era, a remarkable rewrite of an earlier generation of African independence struggles, which had seen white settlers flee en masse the day a black government took the reins. And few doubted that the man at the podium was the right person for the job.

“Unity, conciliation, respect for the rule of law. This was the admirable tone set by Robert Mugabe,” the Monitor’s Africa correspondent Gary Thatcher reported at the time.

For many in Zimbabwe and abroad, Mr. Mugabe, who died Friday in Singapore, was always far more than a president. Like Nelson Mandela or Fidel Castro, he seemed a country personified – in both its brightest days and its most troubled. He spent 37 years as Zimbabwe’s commander in chief, from the country’s early years as the international poster child for the hopeful possibilities of African independence to its slow-motion economic collapse at the turn of the 21st century.

Even after his fall from power in a coup led by his former vice president, Emmerson Mnangagwa, in November 2017, Mr. Mugabe’s legacy hung low over a Zimbabwe marred by economic decay and political brutality.

“The way he spoke of unity at independence, telling people to change their guns into ploughshares, spoke of a leader who was determined to make the country work and be a model democracy in the continent,” said Joice Mujuru, Zimbabwe’s vice president from 2004 until she was ousted by Mr. Mugabe a decade later, in a 2016 interview with the Monitor. But by the end of his life, she says, many had come to believe he had scuttled it all, leaving their country “the laughing stock of the world.”

Yet if Mr. Mugabe’s failings were, by the time of his death, well established, for many, he remained an icon among African leaders, unafraid to take the West to task for its past and present sins on the continent.

“Comrade Mugabe was a shining beacon of Africa’s liberation struggle,” wrote Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta in a statement Friday. “He spent a lifetime challenging Africa to find its place and voice among the Community of Nations, and stand tall. For all these and many other achievements, he will be fondly missed and remembered.”

The hope of a young revolutionary

Mr. Mugabe was born Feb. 21, 1924, in the Zvimba district of what was then Southern Rhodesia, a lush British colony dotted with rolling green farms – home to the country’s large and prosperous white settler population. Like many families, the Mugabes believed the best way for their children to navigate the vastly unequal colonial world they were born into was education. He was schooled at South Africa’s University of Fort Hare, the alma mater of African statesmen from Nelson Mandela to Julius Nyerere. He departed transformed.

“When I left Fort Hare I had a new orientation and outlook,” he later said. “I no longer believed that change was possible from within the system.”

But change was still a long way off for Southern Rhodesia, a fact that frustrated Mr. Mugabe, a young teacher, immensely. In 1960, he left teaching and joined the independence movement. Four years later, he was thrown in jail for “subversive speech.”

When Mr. Mugabe emerged from prison a decade later, the contours of the world around him had changed dramatically. Once buffered by other white-ruled states, Rhodesia was fast becoming an international pariah. But Ian Smith, the segregationist prime minister, still had a white-knuckled grip on power. In 1976 he declared, “I do not believe in black majority rule – not in a thousand years.”

In fact, it would take just three. A grueling guerrilla war led by Mr. Mugabe soon pushed Mr. Smith to the bargaining table, and in September 1979, he agreed to new elections – with universal suffrage – the following year.

The first years after independence were buoyant, and Zimbabwe’s new head of state was the West’s darling, recalled Simba Makoni, then a young deputy minister of agriculture and a rising star in Mr. Mugabe’s Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU–PF) party, in a 2016 interview with the Monitor.

“[He] made us believe we had the greatest leader we could ever get,” said Mr. Makoni, who would go on to become Zimbabwe’s finance minister, and later, to challenge Mr. Mugabe for the presidency.

A hard turn

In the first decade of Zimbabwe’s independence, the country’s rates of infant mortality and malnutrition plummeted, while literacy and life expectancy shot up.

But the cracks were beginning to show.

As the world celebrated Zimbabwe’s progress, the country’s army was carrying out a brutal campaign against the president’s political rivals. Between 1983 and 1987, as many as 20,000 people, many unconnected to the opposition, were murdered across southern Zimbabwe by Mr. Mugabe’s notorious North Korean-trained Fifth Brigade. The operation was called Gukurahundi, or “the rain that washes away the chaff.”

“That was the first time the nation was divided into two,” Ms. Mujuru says. It was then, those close to Mr. Mugabe say, that they began to realize that his revolutionary ideals were at times a mask for a deep and unrelenting paranoia.

“He carried some war-time grudges for the rest of his life,” Mr. Makoni says. “He thought he was surrounded by enemies, especially among fellow liberation war fighters.”

Zimbabwe’s economic backslide, meanwhile, began as it did in much of Africa – with rigid austerity measures imposed by global lending institutions and their Western donors in the early 1990s. The country’s economy contracted sharply. Inflation spiked.

Mr. Mugabe countered in the early 2000s with what was to become his most controversial legacy – his fast-track land reform program, so called because those acquiring the land needed neither to ask nor pay for it. The country’s remaining commercial white farms were taken over, often violently, by groups loyal to Mr. Mugabe.

As images of weeping, bloodied white farmers circled the globe, Western countries rushed to impose sanctions against Mr. Mugabe’s regime, sending the economy further into a tailspin.

But to the president, it hardly mattered. By that time Mr. Mugabe “believed that he was a political god” – untouchable and unassailable – said Jabulani Sibanda, a former leader of the Zimbabwe National Liberation War Veterans Association and a leading participant in the violent farm takeovers, in a 2016 interview.

A complicated legacy

Like much of what Mr. Mugabe did in his lifetime, the legacy of his land reform programs is more complicated than it appears, with a number of studies in recent years remarking that, despite its violence, the program did achieve its goal of transferring arable land into the hands of the poor majority.

What is not in doubt, however, is Zimbabwe’s startling economic collapse near the end of Mr. Mugabe’s life. In late 2008, hyper-inflation in the country reached a darkly comical 79.6 billion percent as the country scrambled to print enough 100 trillion notes. Between 2000 and 2015, the country’s economy halved, and emigration escalated.

Still, Mr. Mugabe continued to rig elections and unflinchingly eviscerate any international observers who dared question their legitimacy. But in the end, his political maneuvers went too far. In 2017, Mr. Mugabe fired his vice president and longtime confidant, Mr. Mnangagwa. In retaliation, Mr. Mnangagwa and the head of the country’s armed forces, Constantino Chiwenga, sent tanks rolling into Harare.

Mr. Mugabe stepped down. Mr. Mnangagwa became president. But the “New Zimbabwe” looked remarkably like the old. The economy, or what little was left of it, continued its tumble. At times, Mr. Mnangagwa’s crackdown on his rivals and dissidents seemed even more extreme than his predecessor’s.

“At the end, Mr. Mugabe was tired. He was ready to go,” said Progress Garakara, whose daughter Aleeya was born the day Mr. Mugabe resigned as president, in an interview with the Monitor last year. “But these [new] guys, you can see they are here to stay.”

‘I’m shooting images instead of people.’ Former guerrilla changes his lens.

Last week by video, militants in Colombia declared war against the government once again. Here’s why Ferley Vargas, both a victim and perpetrator of past violence, won’t be joining them.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Sarah R. Champagne Contributor

For Colombians like Ferley Vargas, violence was a normal part of life. His dad died in his mother’s arms in their kitchen when Ferley was 5. The family fled their home several times with only the clothes on their backs. At 13, Ferley witnessed his mother being dragged from their home by soldiers, accused of collaboration with FARC, the guerrilla movement.

“I didn’t even know that this was conflict,” says Mr. Vargas.

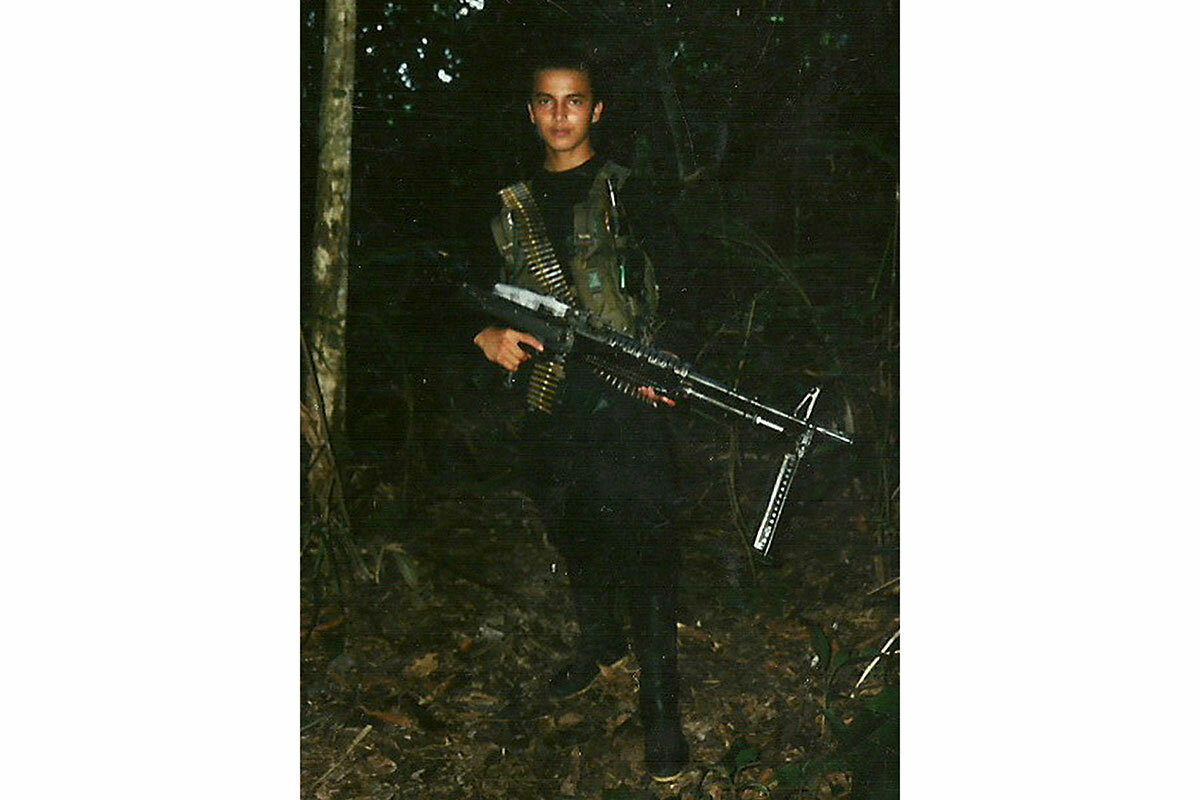

As a teen, he himself joined FARC, also known as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia. “I was never a revolutionary. I liked the war the way a child looks for protection,” he says. After a few years, he wanted out.

Eventually, Mr. Vargas went to school and became a videographer. “I’m shooting images instead of people,” he says. Expressing himself helped reverse his emotional numbness, as he found his voice again. And slowly, he has restored his faith in humanity. “I had to go out of the war to figure out that I was part of it,” he says. “But if I did it, the country can do it too.”

‘I’m shooting images instead of people.’ Former guerrilla changes his lens.

Ferley Vargas might be standing on his former comrades’ graves, but he can’t remember well.

What he does remember is the viscous sensation on his feet a few days after the fight in this green, hilly tract, when he had to carry an injured fellow fighter on his shoulder. Her blood trickled down his uniform and filled his rubber boots. “That kind of thing is hard to wash away,” he says.

Today, Mr. Vargas is also wearing rubber boots, but he holds a camera, not a gun. A TV cameraman, he’s one of more than 10,000 demobilized rebels from FARC, also known as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, which signed a landmark peace accord with Colombia’s government in 2016.

“I’m shooting images instead of people,” he says.

When Mr. Vargas goes back to his childhood village, old acquaintances come to shake his hand; others congratulate him for leaving the FARC and making a go of civilian life.

More than 400 miles south of Bogotá, the road to the tiny strip of houses in Caquetá department is muddy and luminous at the same time, just like Colombia’s path to peace.

Last week, a former top FARC commander known as Iván Márquez issued a new call to arms in a video, accusing the government of failing to uphold the 2016 peace agreement. Alongside him was Jesús Santrich, a former FARC leader and lawmaker who is wanted by the United States for alleged conspiracy to export 10 tons of cocaine.

In total, as many as 3,000 dissident fighters, scattered in small groups, are estimated to be resisting the deal, according to Insight Crime, an organization that tracks organized crime. Mr. Márquez is now trying to unite these factions and work with other guerrillas. President Iván Duque’s government has vowed to track down and capture the rebels in the video, while expressing support for the rehabilitation of former FARC members.

The country has long been divided over ex-combatants’ role in society. Critics of the 2016 peace deal say it was too soft on the guerrillas, granting them 10 seats in parliament. Its defenders argued that it was not a total amnesty, and that the agreement struck a necessary balance between peace and justice.

Weapons down, a first step

Despite this polarization, most people agree that surrendering weapons was just the beginning of a long journey to building a lasting peace in Colombia. After more than five decades of conflict that left 200,000 dead and displaced 6 million people, it can sometimes seem that this country of 49 million has never known anything else.

That was the case for Mr. Vargas. “I didn’t even know that this was conflict. I had to go out of the war to figure out that I was part of it,” he says, his voice rising above the sound of his car wheels spinning in the mud. “But if I did it, the country can do it too.”

Even before “vanishing into the jungle,” he says violence was a normal part of life. When he was 5, his dad died in his mother’s arms in their kitchen. The family fled their home several times with only the clothes on their backs. At age 13, he witnessed his mother being dragged by soldiers from their home to take her to prison, accused of collaboration with the FARC.

Soon after, Mr. Vargas joined the guerrillas. For four years he carried a picture of his father in a coffin. It was his only personal item. The promise he wrote on the back reads, the person “who did that to you will die by my hands. I’m going to take revenge for you so you can rest in peace.”

“I was never a revolutionary. I liked the war the way a child looks for protection,” he says, walking toward the cemetery where his former comrades are buried. Passing a one-story house with closed wooden doors painted in black and a sign that says “Disco,” he stops to shoot a short video with his personal camera: “This is the house where my dad was killed.”

Nearly 3,700 children, 1 in 5 under the age of 15, joined FARC between 1999 and 2016, according to Colombia’s child welfare agency. International humanitarian law forbids the recruitment of soldiers under 15.

It’s hard to know their motives precisely. A 2012 United Nations study of Colombian child fighters suggests that many joined because they believed an armed group would offer them an income, food, or security.

Seeking a way to farm without coca

Leaving FARC behind forced Mr. Vargas to find another way to survive. In Caquetá, the region where the 28-year-old now lives, that is easier said than done. Many farmers in the area still rely on coca for cash income to supplement their subsistence crops.

In San Isidro, three men share a milkshake at a small bakery, before joining a meeting next door with 25 other farmers. The meeting is about converting their coca fields to other crops, and it’s the reason why Mr. Vargas is there. Top of the agenda is the muddy road to town.

“Transportation of goods is the main obstacle for substitution here. What do you want them to grow if they can’t sell anything?” says Balvino Hurtado Polo, a local leader, when Mr. Vargas turns on his camera.

The only visible government presence in San Isidro is a handful of soldiers, who are not here to fix the road but to support a national coca substitution plan.

Colombian government officials insist that peace is only possible if coca growers in former FARC regions like Caquetá convert their crops. “There is a direct relationship between the drug trade and violence,” says Emilio Archila, a presidential counselor for stabilization and consolidation who runs the substitution program.

The program has yet to show results. Since the 2016 peace accord, Colombian coca planting has increased, with a small drop in 2018 to 208,000 hectares, according to the White House’s Office of National Drug Control Policy.

One man’s transition to peace

At the beginning of 2007, Mr. Vargas learned that a member of the FARC was responsible for his father’s execution. His father was accused of being an Army informant; Mr. Vargas says this was untrue.

He deserted the guerrillas soon after, intending to join an anti-FARC paramilitary group. His contact in the paramilitary turned him over to the Colombian police, where he feared he would be shot dead when they officers asked him to surrender. They spent 15 days debriefing him about the guerrillas. Mr. Vargas lied about his age so he could go through the demobilization program faster. But an administrator found out he was still a minor, and he was transferred to a foster home in Bogotá.

The conversion to civilian life was hard: It took him five years to find his purpose. He went back to school and became one of the few demobilized combatants to pursue higher education. He now works for one of Colombia’s largest broadcasters.

“Most of my childhood friends who joined the FARC didn’t have the chance to go out of it,” he says.

Expressing himself helped reverse his emotional numbness, as he found his voice again. And slowly, he has restored his faith in humanity. As the truck roars over the mud, he looks out at a landscape that holds dark memories. “It’s like I can still hear the bullets sometimes. But now I know right from wrong,” he says.

Points of Progress

Meet America’s top-ranked female chess player

Percy Yip thought chess was just for boys – until he saw how well his daughter played. His subsequent push to shift perceptions of the game is emblematic of changes underway in the sport.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

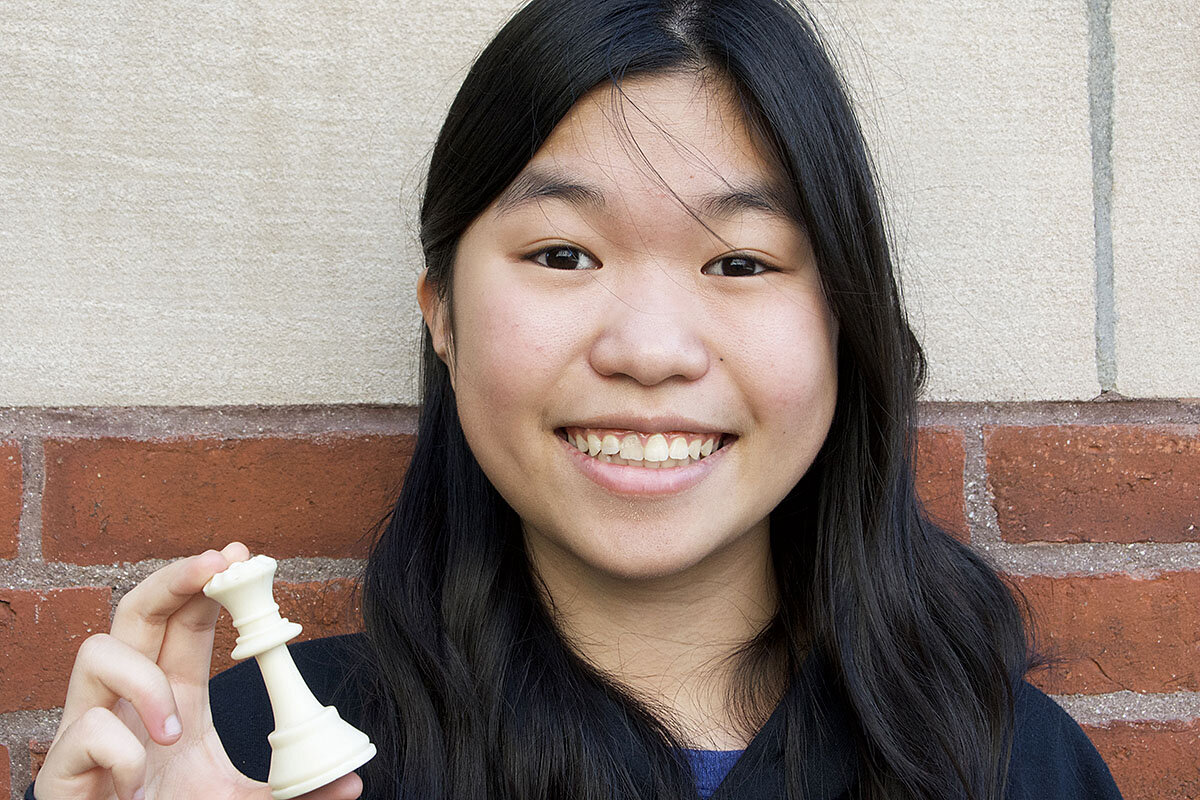

During the summer Carissa Yip, who turns 16 on Sept. 10, spends almost six hours every day studying puzzles and tactics for chess. She is ranked first among women players in America, according to the International Chess Federation, and she’s one rank away from grandmaster.

But decades ago, her success would have been almost unthinkable – not because Carissa is just a high school junior, but because she is a girl.

Until recently there were so few female chess players in tournaments that many questioned whether women could ever be as good as men.

“Why couldn’t a girl be just as good in chess as a boy?” says Susan Polgár, a former top-tier player and women’s chess pioneer. “While it sounds obvious perhaps to most people today, it certainly was not then.”

In 1991, Ms. Polgár was one of the first women grandmasters. Today, more than three dozen women hold the title. In all, 13,000 girls and women are currently competing in the U.S. Chess Federation, the highest number ever, says Jennifer Shahade, former champion player and program director for the USCF’s Women in Chess initiative.

“I can’t imagine my life without chess,” says Carissa.

Meet America’s top-ranked female chess player

Just days before her 11th birthday, Carissa Yip became the youngest female chess player to defeat a grandmaster. Pushing her opponent, Alexander Ivanov, to the back of the board, Carissa pounced on a crucial knight and pinned his queen. A few moves later and the match was over.

“I was feeling really proud of myself for that,” says Carissa, who turns 16 on Sept. 10. “Because when I was younger, I was like, ‘Dang, grandmasters are so good,’ and then I beat one.”

Carissa learned the game from her father, Percy, at the age of 6. She’s now one rank away from grandmaster; last year, she won the girls’ division in the United States Junior Championships. According to the International Chess Federation, she is ranked first among women players in America. Her success – so great and so quick – is remarkable.

But decades ago, it would have been almost unthinkable – not because Carissa is just a high school junior, but because she is a girl. Until recently there were so few female chess players in tournaments that many questioned whether women could ever be as good as men.

“Why couldn’t a girl be just as good in chess as a boy?” says Susan Polgár, a former top-tier player and women’s chess pioneer. “While it sounds obvious perhaps to most people today, it certainly was not then.”

Twenty years ago, fewer than 1% of U.S. Chess Federation players were women, according to Ms. Polgár. Now that number is almost 14%. Jennifer Shahade, former champion player and program director for the USCF’s Women in Chess initiative, says the 13,000 girls and women currently competing in the USCF is the highest number ever.

Large obstacles remain in the way of equal pay and participation, and a fifty-fifty gender ratio may still be far off, Ms. Shahade says. But the numbers are clear: Women are on the rise in chess competitions.

Organizations like the USCF encourage girls to participate through tournaments that network female players at a young age. Having women succeed at the sport’s highest levels makes it easier for more to follow. In 1991, Ms. Polgár was one of the first women grandmasters. Today, more than three dozen women hold the title.

In addition, a larger share of female players boosts the overall quality of women’s chess, Ms. Polgár says. This was also the chief finding from a 2008 study published by the Proceedings of the Royal Society B journal in London. It found that the perceived difference in performance between men and women chess players was a matter of statistics, not a biologically determined skill. The higher number of male players makes it more likely that men will disproportionately rank in the sport’s Top 100 list.

Debunking misogynist theories that men are genetically superior players promotes a more open culture, says Ms. Polgár. The sport’s gender imbalance was so strong that even Mr. Yip was skeptical when his daughter started playing. Wasn’t chess just for boys? Carissa’s success quickly changed his perceptions. Now he’s pushing for a similar shift in others’.

“The reason that it didn’t happen in the past [doesn’t] mean that it will not happen in the future,” he says, referring to equal gender representation in the sport.

In a 1989 interview, chess legend Garry Kasparov commented that there were two kinds of chess: “real chess and women’s chess.” In 2002, Mr. Kasparov lost to a woman – Judit Polgár, Susan’s sister. And in 2016, Carissa received instruction from Mr. Kasparov – now a supporter of women in chess – at a three-day camp for top young players in the U.S.

During the summer, Carissa says she spends almost six hours every day studying puzzles and tactics. Most of her games now last more than four hours. Developing the necessary patience has been difficult, especially for someone with a self-described “killer instinct” on the board. But for her, it’s worth it. She wants to be a grandmaster at the very least.

“I can’t imagine my life without chess,” she says. “I can’t imagine my life before chess, too. ... It’s just a huge part of me.”

Winning, Canada-style: Bianca Andreescu inspires at US Open

Warmth and politeness aren’t the first qualities that leap to mind when we think of top-flight athletes. But for this rising tennis star, those Canadian values mesh seamlessly with power and finesse.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

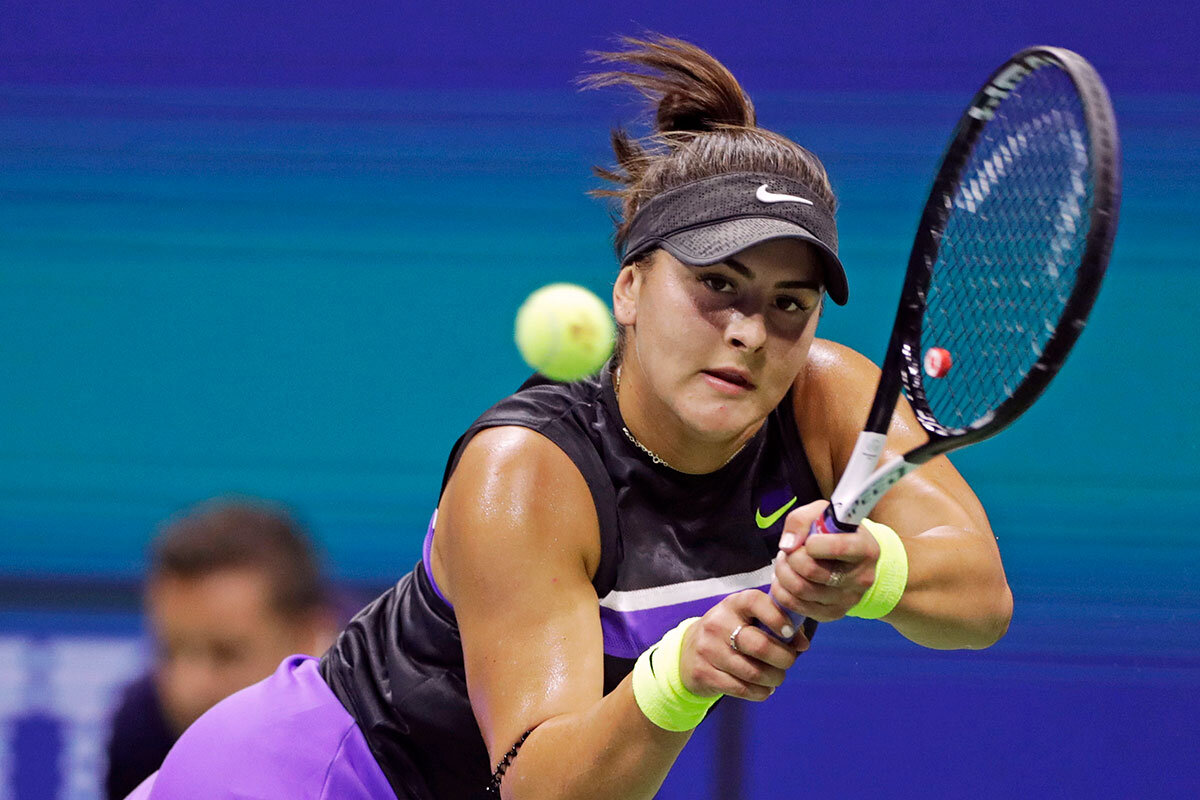

As Bianca Andreescu prepares to play in the U.S. Open final on Saturday night – the first Canadian singles competitor to ever do so – she has Canadians enthralled, and perhaps seeing a bit of themselves in her.

For many Canadians, the Ontario teen and daughter of immigrants seemed to come out of nowhere. For tennis experts, who have watched her gutsy play for years, it’s her “toolbox” that has catapulted her to the top. “She can do a lot of everything,” says Canadian sports broadcaster Ben Lewis.

But her appeal is about so much more than sport. She knows how to play the crowd and those who watch her say she seems to genuinely love it. She has also come of age navigating social media – and thus her branding – but she manages to do it all without being too over the top.

“You could say maybe she has sort of the Canadian politeness,” says Mr. Lewis. “I want to say she's confident but not arrogant. At the same time I think maybe for whatever reason, she hasn't taken notice of just how fantastic a tennis player she is.”

Winning, Canada-style: Bianca Andreescu inspires at US Open

After clinching victory to become the first Canadian to reach a singles final at the U.S. Open, Bianca Andreescu gripped her head looking up to the crowd at Arthur Ashe Stadium and repeated, “Oh my gosh, oh my gosh, oh my …”

It’s that display of disbelief, incongruent to the ferocity of her game, that has endeared the Ontario teen, the daughter of immigrant parents, to the Canadian public.

As she faces Serena Williams Saturday night – a rematch of sorts after the Rogers Cup, where her grace and poise sealed Ms. Andreescu’s place in the national consciousness – she has Canadians enthralled, and perhaps seeing a bit of themselves in her.

Her ascent comes on the heels of another fairy-tale Canadian sports story – the Toronto Raptors becoming the 2019 NBA champs. With #WeTheNorth signs still hanging off balconies across Toronto, the nation woke up Friday to a new hashtag: #SheTheNorth.

Even Prime Minister Justin Trudeau weighed in with a tweet today: “You’ll have a whole country with you tomorrow, @Bandreescu_! #SheTheNorth.”

You’ll have a whole country with you tomorrow, @Bandreescu_! 🇨🇦 #SheTheNorth https://t.co/hhYK8cxnuQ

— Justin Trudeau (@JustinTrudeau) September 6, 2019

For many Canadians, she seemed to come out of nowhere. For tennis experts, who have watched her gutsy play for years, it’s her “toolbox” that has catapulted her to the top. “She can hit hard. She can hit heavy spin. She can use drop shots. She can slice. She can change angles. She can do a lot of everything,” says Canadian sports broadcaster Ben Lewis.

And she just turned 19. The Globe and Mail gushed this morning, “She looks like our next Gretzky.”

But her appeal is about so much more than sport. After victory on Wednesday, she wondered out loud, “I need someone to pinch me right now, is this real life? Is this real life?”

She knows how to play the crowd and those who watch her say she seems to genuinely love it. A teenager, she has also come of age navigating social media – and thus her branding – but she manages to do it all without being too over the top.

“You could say maybe she has sort of the Canadian politeness. I want to say she’s confident but not arrogant. At the same time I think maybe, for whatever reason, she hasn’t taken notice of just how fantastic a tennis player she is,” Mr. Lewis says.

Fair enough. She ended last season ranked No. 178. After Saturday, she will sit in the top 10.

Her rise has come so fast that tennis commentators haven’t gotten all the details right, says Mike McIntyre, who with Mr. Lewis runs the podcast Match Point Canada.

“They went on the air and were saying she was born in Romania, that she was Romanian and moved to Canada. Well that’s not actually what happened. She was born in Canada and spent a couple of years over in Romania. So that just goes to show you that even the experts don’t know all that much,” he says.

They certainly do now – as do the Canadians, many of whom might not have ever even watched a game, reveling in a feel-good immigration story.

One Canadian news director tweeted: “Bianca Andreescu is the superstar Canada needs. Humble, determined, talented, classy. She’s the daughter of immigrants. Her story is THE Canadian story. I love Serena, but Go Bianca!”

Bianca Andreescu is the superstar Canada needs. Humble, determined, talented, classy. She’s the daughter of immigrants. Her story is THE Canadian story. I love Serena, but Go Bianca! #SheTheNorth

— Charmaine de Silva (@char_des) September 6, 2019

Ms. Andreescu just might be the superstar the world needs right now, and it's why the game on Saturday will be so special no matter who prevails. Ms. Williams had to drop out of the Rogers Cup last month due to an injury and was on the bench in tears. Her opponent, Ms. Andreescu, who’d win the competition because of it, came over and wrapped Ms. Williams in a hug.

“I'm so sorry ... I’ve watched you your whole career. You’re a ... beast,” Ms. Andreescu told her courtside.

Ms. Williams laughed – and continued to cry – and later called Ms. Andreescu an “old soul.”

“Bianca just seemed to know how to handle that moment – to cut the tension and to get the crowd to not only feel that sympathy for Serena but also to really see Bianca in a different light that we haven’t seen before,” Mr. McIntyre says. “I asked Serena, ‘What was the most positive aspect of your week here?’ thinking she was going to answer something other than that day where she was injured, and she said this is the most positive moment because of the way Bianca handled it and the way that she sort of reached out to me in that way.”

It’s a moment that some commentators have called one of the best moments in sports this year – and a show of camaraderie that spans well beyond Canada and the world of sports.

Don’t miss it.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Africa rises for immigrant rights

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Since the end of colonial rule, Africans across the continent have rarely experienced spontaneous, grassroots unity around a shared interest. Any solidarity is usually top-down on international issues such as trade or aid. This week, however, thousands of people from Ghana to Mozambique rallied in support of a shared interest: immigrant rights. They did so by condemning violent attacks on hundreds of immigrants in South Africa. At least 10 people died in the black-on-black riots.

The continent-wide reaction made clear that xenophobia – or what some call Afrophobia – should not be in Africa’s future.

This is a hope for shared Pan-African values that can keep in check the kind of nationalism that feeds off fear of foreigners.

Treatment of immigrants is often a litmus test for how a nation sees its identity and relates to other countries. In asking South Africa to change its ways, the rest of Africa is asking for a bigger concept of African identity. The unity behind this request is itself a step toward a different and better continent.

Africa rises for immigrant rights

Since the end of colonial rule, Africans across the continent have rarely experienced spontaneous, grassroots unity around a shared interest. Any solidarity is usually top-down on international issues such as trade or aid. This week, however, thousands of people from Ghana to Mozambique rallied in support of a shared interest: immigrant rights. They did so by condemning violent attacks on hundreds of immigrants in South Africa. At least 10 people died in the black-on-black riots.

The continent-wide reaction made clear that xenophobia – or what some call Afrophobia – should not be in Africa’s future. Two big stars in African music, Burna Boy and Tiwa Savage, announced they would not perform in South Africa. Soccer teams from Madagascar and Zambia declined to play in the country. Demonstrators in Congo stood outside the South African Embassy with signs that read “Don’t kill our brothers” and “No xenophobia.” Many flights to the country were canceled, while officials declined to attend a big meeting on trade in Cape Town.

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa joined the criticism: “There can be no excuse for the attacks on the homes and businesses of foreign nationals.”

Other African leaders went further and called for a Pan-African spirit of unity. “I call for peace between countries and African people,” said Senegalese President Macky Sall.

Twice before, in 2008 and 2015, similar anti-immigrant attacks in South Africa have raised concern on the continent. But with Africans even more connected on digital devices today and with a continental free trade zone just starting, more people are aware of protecting basic rights. Violence among Africans will only hinder “our aspirations for a shared and sustainable prosperity,” says Nigerian billionaire Aliko Dangote.

This hope for shared Pan-African values can keep in check the kind of nationalism that feeds off fear of foreigners. South Africa itself is trying to better connect to its neighbors. This year, for example, students will be taught a common African language, Kiswahili, with the goal of promoting social cohesion with other Africans.

Treatment of immigrants is often a litmus test for how a nation sees its identity and relates to other countries. In asking South Africa to change its ways, the rest of Africa is asking for a bigger concept of African identity. The unity behind this request is itself a step toward a different and better continent.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Comfort

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Brian Kissock

Here’s a poem, originally written in response to a 1998 bombing in the author’s homeland of Northern Ireland, with a message of shelter and assurance in support of those impacted by Hurricane Dorian and other troubles.

Comfort

There is here and there, and everywhere,

A refuge;

A house and habitation;

There is a constant calling to each,

Sean, Samuel, Ruth, Mary.

There is here and there, and everywhere,

A shelter;

Not made with hands,

But high among the peaks,

Whispering stillness.

There is here and now, and evermore,

A Mind;

A Love and a gentling;

There is a peace saying,

Be still, I am, I am that peace.

There is here and there, and everywhere,

A goodness;

A life without blemish,

A way of looking on the world,

Undisturbed.

There is here and now, and evermore,

A rest;

Protection from the storm,

Always hid with Christ,

In God, eternally.

Originally published in the June 30, 2003 issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Photos of the week

A look ahead

Join us again Monday, when we’ll feature a report from Uganda on what a promised influx of Chinese investment really means for Africa.