- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- ‘See the fire’: George Floyd and the effects of violent protest

- Feeding America during COVID-19: How food pantries meet record demand

- The pandemic is accelerating mail-in voting. Is the US ready?

- ‘The last person to know’: What the lockdown means for one deaf driver

- During 2020’s wild ride, rediscovering video games

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

On George Floyd, injustice, and being my brother’s keeper

Excessive force by police and destructive protests have deeply shaken America. But two bystander videos posted Sunday may hint at how to deal with both problems.

In the first video, two police officers in Seattle are handcuffing a male protestor on the ground. One cop’s knee is on his neck – the same technique used on George Floyd. Then, the second cop intervenes, forcibly removing his partner’s knee.

That’s what’s supposed to happen, Clarence Castile told NPR, discussing the death of Mr. Floyd: “When one cop sees another cop using excessive force. ... that cop’s supposed to say ...“Yo man, get up off him.”

Mr. Castile became a reserve police officer in St. Paul, Minnesota, after his nephew, Philando Castile, a black man, was fatally shot by a cop in 2016.

A second video on Twitter shows a black female protester confronting two white women spray painting “BLM” on a Starbucks in Los Angeles. She reprimands the vandals as they walk away: “They’re gonna blame black people for this and black people didn’t do it. ... You all are part of the problem.”

Racial injustice is a chronic problem. But Mr. Castile insists progress can be made now if we act as our brother’s keeper. Cop to cop. Protester to protester. “Me accountable to my neighbors, my neighbors accountable to me and everybody helping everybody out,” he says. “We all have a small part to play in the big picture.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

‘See the fire’: George Floyd and the effects of violent protest

Can protest violence ever be a moral act? The United States is grappling with how to respond to the looting and destruction now sweeping nightly through some American cities.

-

By Patrik Jonsson Staff writer

Is violence an effective way to change society?

The question arises because looting and burning have erupted in some cities during protests sparked by the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer. While law enforcement officials and other authorities have condemned the violence as lawlessness, some demonstrators have defended it as means of getting the attention of a nation too eager to ignore the problems of African Americans.

“If all 50 states have to see the fire in order for justice to prevail, then so be it,” said Karen White, a middle-class mom marching in Savannah, Georgia, over the weekend.

Violence against property, despite the risks, may be a last-choice tool for change if a moral imperative makes it justified, say some experts.

“Property damage and social turmoil often do promote more social change as they force the authorities to pay attention,” says Pam Oliver, a professor emeritus of sociology at the University of Wisconsin who tracks media response to social unrest, in an email.

But “property” is a key word. Many people make a big distinction between property damage and hurting people, she says.

Meanwhile, David Harris, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, has a somewhat different opinion. However real the pain and anger, however rational it seems to resort to violence to gain attention, it inevitably allows those who would prefer to ignore real underlying issues to look away and stop discussing what happened.

“The president isn’t talking about George Floyd or a systematic failure to correct police accountability. He’s talking about the violence he sees on his TV screen,” says Mr. Harris.

‘See the fire’: George Floyd and the effects of violent protest

After the killing of George Floyd by a white policeman in Minneapolis last Monday, Karen White cried.

“I cry for George Floyd because I cry for my sons,” the black middle-class Savannah mom said while marching peacefully along with 2,000 people on Sunday.

The killing of a black man by a policeman’s knee to the neck awoke something in Ms. White, by her own account. The old her would have been horrified by images of people looting and setting fires to protest police violence. But now, she says, such offenses against property seem apt in the face of systemic racism.

“If all 50 states have to see the fire in order for justice to prevail, then so be it,” says Ms. White.

As protests intensify from Washington, D.C., to Walnut Creek, California, the morality of protest violence is being debated in new ways in a nation roiled by the reaction to a Minneapolis policeman choking Mr. Floyd.

To be sure, the vast majority of the demonstrations are peaceful.

But some aggressive elements within the crowds continue to clash with police, especially after dark, and especially in places where authorities have responded to protests with their own violent means, such as tear gas and rubber bullets.

The protesters have angered President Donald Trump, who on Monday called state and local leaders “weak” for failing to “dominate” them. Former President Barack Obama, with more measured language, urged an end to the destruction of property in an essay released Monday on Medium.

“If we want our criminal justice system, and American society at large, to operate on a higher ethical code, then we have to model that code ourselves,” Mr. Obama wrote.

Yet to many like Ms. White, what they see as intractable systemic racism and unjustified police killings of black Americans has begun to give legitimacy to what the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. called “the language of the unheard”: riots in the face of injustice.

“There are elements here that I have not seen before, including that I’m hearing the perspective that perhaps the violence isn’t as nihilistic as authorities make it out to be,” says Darnell Hunt, author of “Screening the Los Angeles ‘Riots’: Race, Seeing and Resistance.” “It seems different this time because you are hearing echoes of something bigger.”

American reckoning

The impulse of authorities to blame agitators and step up the response to “dominate” the streets goes back to the 1960s when Richard Nixon rode to presidential victory in part by exploiting racial tensions and promising law and order.

Nixon’s strategy found fertile ground in an America then reeling from widespread riots in the long hot summer of 1967, and following the assassination of Dr. King in 1968. Back then National Guard and regular Army units deployed to city streets to bring widespread looting and burning under control.

Today America as a whole is facing a similar reckoning, says Dr. Hunt. The U.S. has suffered through numerous well-publicized incidents of people of color being killed after being falsely profiled as suspicious. Even before a self-appointed Florida neighborhood watchman named George Zimmerman shot a teenage boy, Trayvon Martin, in 2012, the beating of Rodney King in 1992 and the killings by police of Amadou Diallo in 1999, Sean Bell in 2006, and Oscar Grant in 2009 had been ingrained in the national consciousness.

The death of Mr. Floyd was only the latest such incident. Meanwhile well-armed white men who shuffled inside the Michigan Capitol to “liberate” the state from its pandemic closure were treated gently, says Jennifer Cobbina, author of “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot” and a criminal justice professor at Michigan State University in East Lansing.

Yet peaceful protesters marching in Washington in response to Mr. Floyd’s killing were tear-gassed so President Trump could stand in front of a church.

“There’s a stark contrast in the response to when there were angry white men protesting with assault rifles against lockdown orders and were met by a police force that was very calm,” says Dr. Cobbina. “Yes, people are looting and rioting ... but the contrast remains stark because we see different reactions depending on who is demonstrating. [The situation] shows how the demographics of the people protesting shapes the police response.”

Meanwhile, in Greater Los Angeles, demographics figured in protesters’ larger strategy.

Organizers specifically chose upscale areas such as the gentrified downtown, Beverly Hills, and the beachside community of Santa Monica to bring their message home.

“We’ve been very deliberate in saying that the violence and pain and hurt that’s experienced on a daily basis by black folks at the hands of a repressive system should also be visited upon, to a degree, to those who think that they can just retreat to white affluence,” Melina Abdullah, a Los Angeles Black Lives Matter leader, told KPCC radio on Sunday morning.

In a pattern repeated throughout the weekend, demonstrations would begin peacefully, and then looting would set in into the night.

Los Angeles police and political leaders are publicly voicing support for the peaceful demonstrators and dismay at the death of Mr. Floyd. But they are condemning the looters, who they say are well organized and not from the area.

Similar claims made by authorities in other cities have been undermined by the facts. Minneapolis officials had to walk back charges that many protesters were infiltrators after a media analysis of public records showed that the vast majority of those arrested were Minnesotans. New York Mayor Bill de Blasio argued that the bulk of the troublemakers were out-of-towners, but this week his daughter was arrested during a protest.

The crumbling of the “out-of-towner” trope is evidence that authorities and the mainstream media are having a hard time controlling and shaping the narrative of the Floyd uprisings, says Dr. Hunt, dean of social sciences at UCLA.

Historically, “the media has traditionally parroted the official mind, ... minimizing the importance of what’s actually happening in the streets,” says Dr. Hunt, the dean of social sciences at UCLA. He senses a different arc of coverage this time.

Violence and attention

Nonviolence has a storied position in the civil rights movement. King famously espoused nonviolence as the most effective means of lifting up black Americans.

But violence against property, despite the risks, may be a last-choice tool for change if a moral imperative makes it justified, say some experts.

“Property damage and social turmoil often do promote more social change as they force the authorities to pay attention,” says Pam Oliver, a professor emeritus of sociology at the University of Wisconsin, who tracks media responses to social unrest, in an email.

Historically, she says, that has been a “two-edged sword” as focus shifts from the underlying structures to the scope of violence. But many Americans, she says, seem to be reassessing the meaning of violence with respect to property damage. In Minneapolis, for example, one owner of an Indian restaurant that went up in flames told friends and relatives, “Let my building burn. Justice needs to be served.”

The difference now, “as you are seeing, [is that] many people make a moral distinction between property damage and hurting people.”

David Harris, author of “A City Divided: Race, Fear and the Law in Police Confrontations,” has a somewhat different opinion. He has watched the violence vs. nonviolence scenario play out just miles from his house in Pittsburgh, where protests turned violent Saturday and where there was more conflict Monday night, allegedly exacerbated by the police response.

“The pain and the anger are real and great and, honestly, rational,” says Mr. Harris, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law. “The concern is that when the protests become violent either against property or the police, even if you can make an argument that it is somehow understandable, what happens is that those who would prefer to ignore the underlying and real issues all of a sudden have a way to stop discussing what happened.”

“The president isn’t talking about George Floyd or a systemic failure to correct police accountability. He’s talking about the violence he sees on his TV screen,” says Mr. Harris.

Meanwhile, one positive development highlighted across the U.S. in recent days is evidence that protesters are not strictly anti-police. In Savannah and elsewhere, protesters have urged police to “walk with us!” Some have.

Over the past week, that pattern has sharpened, as police strategy has been divided between escalated use of force and what’s called “negotiated management” where officials take a hands-off approach amid assurances from organizers that protest remains peaceful.

Crackdowns have multiplied violence, says Ms. Cobbina. Acknowledgment and solidarity have won hearts – and limited damage. That dynamic could be seen in Newark, New Jersey, a city where 26 people were killed in riots in 1967, but where there were no arrests on Sunday despite a large, raucous protest.

Staff writer Francine Kiefer contributed to this report from Los Angeles.

Feeding America during COVID-19: How food pantries meet record demand

Our next story is a portrait of generosity in a pandemic. America’s food pantries face dwindling supplies and skyrocketing need. But with tenacity and heart, they’re stepping up to the challenge.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By G. Jeffrey MacDonald Correspondent

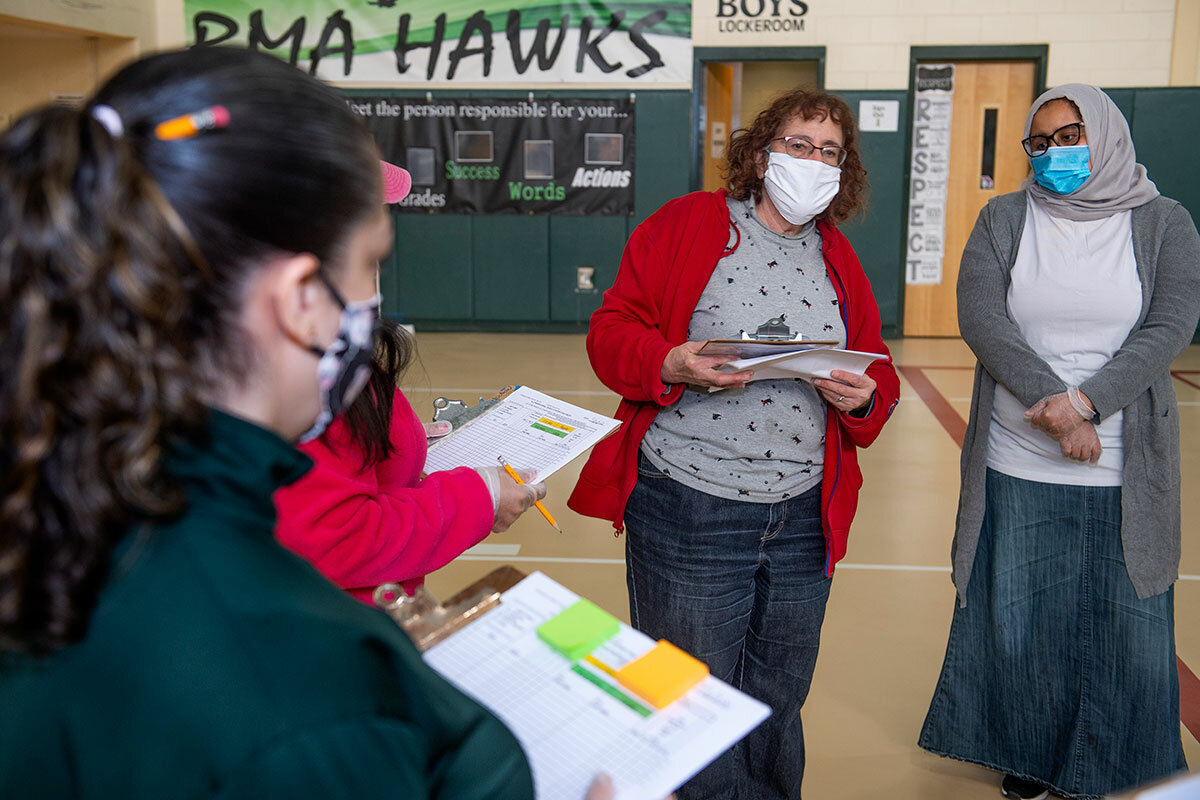

Inside Rumney Marsh Academy, a middle school converted into an emergency food pantry in Revere, Massachusetts, volunteers stuff bags with groceries in assembly-line fashion. Among them is David Eatough, a Revere High School biology teacher. Volunteering comes with health risks. But Mr. Eatough feels the risks are manageable – and worth it.

“I’m helping [the community] and at the same time helping myself by keeping busy,” Mr. Eatough says. Volunteering at the pantry “alleviates some of that sense of helplessness that I think all of us feel to some degree.”

Volunteers like Mr. Eatough are much needed right now. America’s network of some 40,000 food pantries is facing a perfect storm of challenges spawned by the coronavirus outbreak. Needs, costs, and pantry closures have spiked simultaneously. Pantries gave out 32% more food in April than a year earlier, according to Feeding America, as the number of food-insecure Americans jumped from 37 million in 2018 to as many as 54 million today.

“The emergency food system is dependent on charitable organizations, on volunteers, on quick adaptability – and that’s been challenged during this time,” says Alicia Powers, of the Hunger Solutions Institute. “These systems have been tried in ways that we never imagined.”

Feeding America during COVID-19: How food pantries meet record demand

On a crisp May evening, Wendy Baur had earned a rest by the time dusk fell on a middle school gymnasium that was transformed into a supersized food pantry for the pandemic. Responding to a 630% increase in need since mid-March, she and her team of 55 volunteers had just handed out full grocery bags to about 375 families reeling from this gateway city’s economic collapse. It was time to go home.

But Ms. Baur, who’s directed the First Congregational Church of Revere food pantry in Massachusetts for 18 years, wasn’t relaxing as she leaned on a stack of canned soup cases. She was worrying. If even one volunteer tests positive for COVID-19, she said, the operation might grind to a halt as all contacts would have to quarantine. Just as concerning: the prospect of running out of food.

“Every week it’s a struggle to resupply, to get more food,” says Ms. Baur, who also runs a research lab at Tufts Medical Center. “All of the food pantries are competing for a time slot at the food bank warehouse. Some days I can’t even get a slot. ... I get online at midnight when you can pick your slot, but when I get on, they’re all taken. They’re gone within one second.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Such anxieties aren’t unique to this pantry in Revere, a city of 53,000. America’s network of 40,000 food pantries, which give away food as part of a patchwork emergency system, is facing a perfect storm of challenges spawned by the coronavirus outbreak. Need, costs, and pantry closures have spiked simultaneously. Volunteers including Ms. Baur now scramble to prevent what happened in Revere in mid-March, when the pantry ran out of food for the first time in its 36-year history and had to turn people away.

Unprecedented challenges

Nationwide, as many as 10,800 pantries and meal programs have shut down since the pandemic began, according to figures from Feeding America, a network of 200 food banks serving pantries and meal programs. One reason: not enough volunteers. Many were run by seniors who are now high risk and stay home to avoid the virus. Others have had to close after someone tested positive for COVID-19.

Meanwhile, need has skyrocketed. Pantries and meal programs gave out about 32% more food in April than a year earlier, according to Feeding America, as the number of food-insecure Americans jumped from 37 million in 2018 to as many as 54 million today.

“The emergency food system is dependent on charitable organizations, on volunteers, on quick adaptability – and that’s been challenged during this time,” says Alicia Powers, managing director of the Hunger Solutions Institute at Auburn University in Alabama. “These systems have been tried in ways that we never imagined.”

What’s more, staples are getting more expensive – if pantries can find them at all. The Greater Boston Food Bank used to be able to offer pantries more options at no cost, but lists of available free items are getting shorter and shorter, according to Vice President of Distribution Services Jonathan Tetrault.

“At this point, the options to choose from are diminishing because of the supply chain challenges,” Mr. Tetrault says. For no cost, pantries were able to get pasta, white rice, brown rice, black beans, pinto beans, and kidney beans. “Now your option this week is white rice only and one type of bean.”

Grocery chains have been selling out of items like canned vegetables, leaving them with less to donate to food banks, according to Feeding America spokesperson Zuani Villarreal. That leaves pantry organizers having to pay at food banks or buy from stores at a time when everything from eggs to meat is costing more due to heightened demand and scant supply.

Since the pandemic started, “I have to buy more at the store, and I have to pay more for it,” says Linda Crocker, a volunteer pantry coordinator at The Memorial Church of the Good Shepherd in Parkersburg, West Virginia. In normal times, she spends about $1,000 a month to stock her pantry to feed about 45 families. Now with less at food banks, higher prices in stores, and more families seeking help, her spending has jumped by about 30%.

Meeting growing needs

New challenges facing pantries are on display every Wednesday night here at Rumney Marsh Academy, which the city of Revere converted to an emergency food hub soon after schools closed for the pandemic. Prior to March, the pantry (Revere’s only one) had been located at the church, where a human chain would pass bundles up from the basement through a hole in the floor. But that was when 8,000 pounds of food and supplies a month was enough. Now the pantry is going through upward of 40,000 pounds a month. Moving temporarily to the larger school facility on a state highway was essential.

Before distribution begins at 7 p.m., more than 100 cars form two lines that wind around the building. Dozens of pedestrians line up beside them on a sidewalk. Everyone is wearing masks. Guidelines to stay six feet apart are loosely followed.

On this night in mid-May, 72% of pantry visitors are Hispanic, up from 33% in mid-March, according to Ms. Baur. Speaking in Spanish, one guest after another tells a similar story of layoffs. Jose Santiago lost his janitorial job at a food processing center. Leticia Restrepo is no longer cooking at a restaurant. Jorge Tovon can’t work at the airport hotel where he’s tended a bar for 14 years. All have stretched their personal accounts for weeks, then started coming to the pantry in May because it was getting tougher to provide for family members who depend on them.

“I was embarrassed to come here, but now we need it,” says Angela, who asked that her last name not be used. She thought her furlough from office work would be brief, but two months later she’s still unemployed.

“People see the need”

Inside, volunteers stuffing bags in assembly-line fashion say it’s just their second or third week at the pantry. Among those answering the call for helpers is David Eatough, a Revere High School biology teacher. He’s seen up close what it means for Revere to have one of the higher infection rates in Massachusetts. Two students at the high school lost a parent to the virus, he said, and a former student has died as well.

Volunteering comes with health risks. But Mr. Eatough feels the risks are manageable – and worth it. Like other volunteers, he wears gloves, keeps his mask on, and fills bags to feel helpful in a situation that’s left many feeling helpless.

“I’m helping [the community] and at the same time helping myself by keeping busy,” Mr. Eatough says. Volunteering at the pantry “alleviates some of that sense of helplessness that I think all of us feel to some degree.”

Behind the scenes, Ms. Baur aims to keep one wall of the gymnasium stacked 6 feet high from end to end with chickpeas, canned tomatoes, pasta, and other goods. She takes pride in stocking protein such as ground turkey, cheese, and frozen eggs, which are stored separately in a school kitchen.

But the logistics can be daunting. On her June to-do list: lining up a reliable volunteer trucker, if needed, to transport supplies.

In the meantime, she stretches her budget by stocking up on whatever she can get free from the food bank, such as cases of USDA peanut butter. For a 5,000-pound midweek delivery, she paid for only three items: 480 jars of jelly – “it goes with the peanut butter” – 2,000 shopping bags, and a case of gloves for volunteers. Total: $601.

Now as she prepares to leave for the night, her phone rings. It’s her pastor with good news: The pantry got a $10,000 donation from a Boston health care organization. She can use it. The pantry spent about $10,000 on food in April, a 10-fold increase from a year earlier.

“Sometimes it can be 6,000 pounds and I’m paying $1,000 because none of the stuff I want happens to be free,” Ms. Baur says. “On the plus side, there have been a lot of donations. People see the need.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

The Explainer

The pandemic is accelerating mail-in voting. Is the US ready?

We know that voting integrity is a democratic cornerstone. But how the U.S. protects the accuracy of the vote during a pandemic is now a matter of hot debate.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Amid concerns that the pandemic will prevent equal access to voting, many states are moving to expand opportunities to vote by mail. Five states – Colorado, Hawaii, Oregon, Utah, and Washington – already vote entirely by mail, which means all registered voters are automatically sent a ballot.

That is distinct from absentee voting, which requires voters to apply for an absentee ballot before being sent one. All states allow absentee voting, though about a third usually require a reason.

Key areas of partisan disagreement: requesting ballots online, free return postage, witness signature requirements, and perhaps most important, how each state will establish standards governing disqualification of ballots. Two dozen legal challenges have already been launched.

Educating voters, scaling up equipment, and refining rules and procedures in a matter of months is a tall order; the five vote-by-mail states gave themselves a year. Rushing it could lead to greater inaccuracies; already, tens of thousands of absentee ballots have been disqualified in previous elections.

With six key swing states allowing “no excuse” absentee voting this November, even relatively minor numbers of disqualified ballots could tip a tight race, and potentially determine who will become the next president.

The pandemic is accelerating mail-in voting. Is the US ready?

Many states have expanded mail-in voting ahead of the 2020 election in order to ensure fair access for all amid the ongoing pandemic. This has led to concerns that the expected surge in people voting by mail, could lead to delays and inaccuracies that would undermine faith in the election results.

Is mail-in voting the same as absentee voting?

No. Absentee voters must request a ballot to be mailed to them. Mail-in voting states send every registered voter a ballot automatically.

Currently, all states allow absentee voting. However, a third require voters to provide a reason for why they cannot vote in person. Most of those states have eased their rules, including by making COVID-19 concerns a valid reason for requesting an absentee ballot.

Prior to the pandemic, five states voted entirely by mail: Colorado, Hawaii, Oregon, Utah, and Washington. Three additional states – California, Nebraska, and North Dakota – allow counties to institute voting by mail if they so choose. And nine more states allow certain elections, such as special elections or nonpartisan issue elections, to be done entirely by mail.

This year, with the pandemic exacerbating concerns about lack of safe access to polling places, at least half a dozen states are mailing every registered voter an absentee ballot application in upcoming primaries. Two of those – Connecticut and Michigan – are doing so for the November general election as well. California Gov. Gavin Newsom has gone a step further, saying he would automatically send the state’s more than 20 million voters absentee ballots without an application process.

What are the challenges to expanding mail-in voting?

The first challenge is the rushed time frame. Most of the current vote-by-mail (VBM) states gave themselves a year between enacting the legislation and conducting their first elections by mail. One reason for that is the need to bring voter lists up to date. Some also establish a database of voter signatures used to certify the authenticity of absentee voting.

Second is the infrastructure required. A surge in mailed ballots would require much more powerful scanning machines at centralized locations, rather than smaller ones in each precinct. The $400 million that Congress allocated this spring to help states safely run elections amid the pandemic is not likely to cover such a major equipment overhaul.

Another issue is voter education campaigns to ensure that citizens are clear on the revised rules, including when ballots need to arrive in order to be counted. Such campaigns can present substantial up-front costs. (However, in the long run VBM can cut costs; Colorado saved 40% on election administration costs after switching to the VBM model.)

In addition, there are concerns about the reliability of the U.S. Postal Service, which was already in deep financial trouble before the pandemic led to a double-digit drop in mail volume.

While both Republican- and Democrat-led states are making it easier to cast a ballot by mail, key areas of partisan disagreement are: requesting a ballot online, free postage, witness signature requirements, and perhaps most important, how each state will establish standards governing disqualification of ballots. Two dozen legal challenges have already been launched.

What are the concerns?

Democrats are concerned that without increasing vote-by-mail options, certain groups will not be able to cast ballots without risking their health, therefore undermining a pillar of U.S. democracy. They have proposed billions of dollars in federal funding for states that institute uniform practices, including adopting VBM systems. Republicans argue that such a move trespasses states’ rights under the Constitution, and raises the possibility of substantial inaccuracies.

Among the concerns are ballot design flaws that mislead voters, voter confusion over the deadline for submitting ballots, delays in tallying votes, and signature mismatches that result in disqualification of ballots. In previous years, substantial numbers of absentee ballots have been disqualified – sometimes many more than the margin of victory. For example, when Al Franken won the 2008 Minnesota Senate race by 312 votes, giving Democrats the majority they needed to pass Obamacare, about 12,000 absentee ballots were thrown out. In some elections, such as Florida in 2016, minorities and young people have seen their ballots disqualified at far higher rates.

While the number of known cases of voter fraud is extremely low – one study put it at less than 0.00000013% of ballots cast in federal elections – absentee voting is more susceptible to fraud than other forms. A bipartisan commission on federal election reform co-chaired by former presidents Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter concluded that absentee voting cases are “especially difficult to prosecute, since the misuse of a voter’s ballot or the pressure on voters occurs away from the polling place or any other outside scrutiny.”

A little-noticed change to California law in 2016 paved the way for anyone – including paid campaign workers – to collect absentee ballots on behalf of voters, raising concerns about coercion not only from friends or family members, but campaigns themselves. In the 2018 midterms, Republicans were caught off-guard by this practice, which they dubbed “ballot harvesting,” as tight races tipped against them after absentee voters were counted.

Meanwhile, a GOP operative from North Carolina was charged with several counts of obstruction of justice for allegedly filling in ballots for absentee voters. The election was ordered thrown out and redone.

With “no excuse” absentee voting in the six key swing states likely to determine the winner in November’s presidential election – Arizona, Florida, North Carolina, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin – even relatively minor numbers of disqualified ballots or other irregularities could tip a tight race, and potentially determine who will become the next president.

‘The last person to know’: What the lockdown means for one deaf driver

One of the ironies of the pandemic is that although we face a common challenge, everyone’s experience is very different. Our reporter takes an empathetic look at what lockdown has meant for a deaf boda-boda driver in Uganda.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By John Okot Correspondent

Denish Komakech felt like he was the last person in the world to learn about the coronavirus.

Since he lost his hearing at the age of 2, he has navigated the world without sound. And that means he often misses important announcements, including the Ugandan government’s lockdown order in late March.

“Do you know how it feels like to always be the last person to know about any serious issue because you are deaf?” he says in an interview with the Monitor through a sign-language interpreter.

For Uganda’s informal workers, especially those living with disabilities, the lockdown creates a complicated situation.

Being a motorcycle, or boda-boda, driver in Uganda is tough work in the best of times. Although motorcycles are allowed on the streets during the lockdown, drivers are only permitted to carry cargo, and only until 5 p.m., before a nighttime curfew goes into place.

Mr. Komakech cannot help but get his hopes up that one day soon, the restrictions will ease. For now, all he thinks about is the day ahead. To survive it and see another – for now that will have to be enough.

‘The last person to know’: What the lockdown means for one deaf driver

Most people would have noticed the quiet. When Uganda introduced more restrictive COVID-19 lockdown measures in late March, it was as though someone had turned down the volume on the entire country. Gone were the throaty revs of cars starting and stopping in the choking rush-hour traffic, and the frantic voices of sports commentators spilling out the doorways of the city’s ubiquitous sports betting centers, the fresh eggs sizzling in pans at roadside omelet and chapati stands, the chatter of taxi touts and hawkers gathered on street corners.

But motorcycle driver Denish Komakech didn’t miss any of that. Since he lost his hearing at the age of 2, he has navigated the world without sound. So what struck him that first day of the lockdown wasn’t the quiet but the stillness. As he rode his motorcycle into town looking for passengers, he saw that the streets were nearly empty except for baby-faced soldiers with big guns and a few plucky vendors selling bits of soap, salt, or sugar to the occasional passerby. Finally he stopped to ask a friend what was going on. A lockdown, the man explained in sign language. To stop the coronavirus.

“Do you know how it feels like to always be the last person to know about any serious issue because you are deaf?” says Mr. Komakech, speaking to the Monitor through a sign-language interpreter. “That is how I felt – like I had been that last person to hear about the lockdown and the pandemic.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Being a motorcycle driver in Uganda is tough work in the best of times. The country’s urban roads are choked with bikes, known locally as boda-bodas, swerving precariously through traffic as they rush to carry riders and the teetering stacks of their cargo across town as quickly as possible. Profit margins are razor thin, and police harassment and accidents common. (A 2010 study at the country’s largest hospital found that a full 75% of patients admitted for trauma injuries sustained in traffic accidents had been involved in boda-boda crashes.)

But the job had always been harder for Mr. Komakech, who communicates with his customers on slips of paper and via text messages.

And on top of that, these are certainly not the best of times.

In mid-March, before Uganda had even a single confirmed coronavirus case, President Yoweri Museveni announced a 32-day ban – since extended – on public gatherings, and closed schools, churches and restaurants. He followed up at the end of the month by banning all public transport except for cargo, effectively shutting down business for most of the country’s boda-boda drivers.

Although motorcycles are allowed on the streets during the lockdown, drivers are only permitted to carry cargo, and only until 5 p.m., before a nighttime curfew goes into place. Police have been impounding boda-bodas from drivers who violate these restrictions, and ordering them to pay a hefty fine to have their bikes returned.

For Ugandans like Mr. Komakech, that creates a complicated situation. He is part of the 80% of Uganda’s workforce that works informally, according to government estimates – millions of cleaners, drivers, hawkers, and others who make their living day to day, in cash.

Most, including Mr. Komakech, have received no support from the government since the lockdown began. And if they can’t work, many have asked, how will they eat?

“When I realized that we had been stopped from riding our boda-bodas, many thoughts ran through my mind, like how it was going to be tough to look after my family,” he says.

But Mr. Komakech is no stranger to health crises. He was only two years old when he and his brother were diagnosed with measles. His brother died. Mr. Komakech survived, but lost his hearing.

Since then, he has relied on a combination of sign language, written notes, and lip-reading to get by. He says he is often harassed by the police and cheated by his riders when they realize he will struggle to argue back.

Ugandan activists for people with disabilities say people like Mr. Komakech are especially at risk during the country’s coronavirus lockdown: in part because, doctors say, some disabilities compromise the immune system, but largely because people with disabilities have often had traumatizing experiences with the health care system, or are afraid to seek medical care. And many, like Mr. Komakech, don’t have the same access to public service announcements, billboards, or other forms of public health messaging as the rest of their community.

“The government failed to consider people with disabilities right from the beginning when they came up with lockdown restrictions,” said Denis Lakwonyero, an activist and Gulu district councilor representing persons with disabilities in local government. “Yet people with disabilities are the most vulnerable in this crisis.”

For now, though, Mr. Komakech is less worried about the disease and more worried about how he will keep paying his family’s bills. Those thoughts press down hard on him as he rides his boda-boda into town each morning, looking for people who need items transported somewhere.

As Uganda’s government has begun to loosen restrictions on cars, buses, and taxis in recent weeks, Mr. Komakech has listened hopefully for an announcement that boda-boda drivers will once again be able to carry passengers. So far, however, President Museveni has said that motorbikes will still only be allowed to carry cargo because of the close physical contact required to ferry people.

Still, Mr. Komakech cannot help but get his hopes up that one day soon, the restrictions will ease. He has a large, unpaid bill for a recent hospital stay by his daughter, and soon his family will need to hire someone to help them clear their small plot of farmland to prepare for the planting season. Before the lockdown began, he had been taking driving lessons and saving to buy a secondhand car. There is more money, after all, in driving taxis than in driving boda-bodas.

For now, however, the restrictions remain. And so Mr. Komakech has tried to reign in his horizons. For now, all he thinks about is the day ahead. To survive it and see another – for now that will have to be enough.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

During 2020’s wild ride, rediscovering video games

In a pandemic, some people bake. Our reporter is among those who are finding comfort, companionship, and relief in video games.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

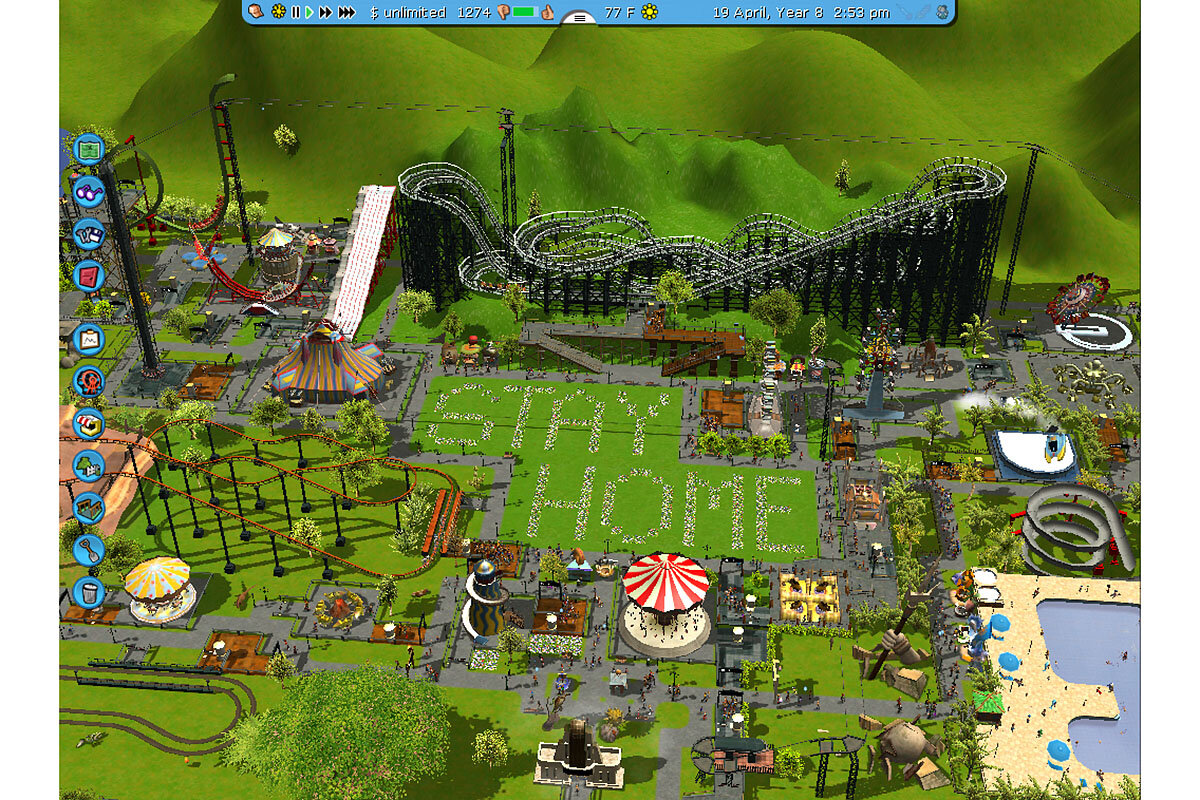

It’s not easy being a roller coaster mogul, but someone has to do it. At least, that’s what I told myself as I logged into RollerCoaster Tycoon for the third night in a row.

It had been 15 years since I played that classic video game, but during the pandemic, it has provided a crucial escape from the small Rhode Island apartment I’m sharing with three other people. Video games tend to have a bad reputation, but they’ve become a source of comfort for many in a time of physical and social restriction. Game sales spiked in March and April, and the influx of new and returning players is helping chip away at gamer stereotypes.

Allegra Frank, host of a video game podcast, has spent much of her down time playing the wildly popular island-life simulator called Animal Crossing: New Horizons. She sends pictures of the game to friends, and “Even if we’re not playing together, we’ll compare notes,” says Ms. Frank. “So games that aren’t multiplayer can still be social. And I think that’s also a really important part of why these games are so pleasurable right now.”

During 2020’s wild ride, rediscovering video games

On day 60 of the lockdown things were not going well in my universe. My guests were starving. Families were trapped on a merry-go-round. And an ostrich named Ophelia was on the loose.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. My return to the RollerCoaster Tycoon video game after a 15-year hiatus was supposed to be an escape from the cramped Rhode Island apartment I’m sharing with three other people, an opportunity to regain the sense of power and control I felt playing as a kid. Instead, mayhem.

But logging on to the classic amusement park simulator is still a refreshing change of pace, and it seems I’m not the only one finding comfort in video game nostalgia. According to NPD Group, U.S. consumers spent more than $3 billion on games, consoles, and accessories in March and April, as lockdowns spread across the country. While some folks are using this time to unplug, finish home projects, and bake bread from scratch, others are leaning into digital hobbies.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

“A lot of people do play [video games] as a form of escapism,” says Jose Aviles, an assistant professor of communications at Albright College in Reading, Pennsylvania, who studies gaming. “In a time where a lot of people are stressed out, and not sure what’s going on around them, they could turn to video games” for relief. Used in moderation, says Dr. Aviles, video games offer a chance to build problem-solving skills and connect with other players – a bonus at a time when the masses are practicing social distancing.

This trend is no more apparent than in Nintendo’s Animal Crossing: New Horizons. Like the Tycoon and Sims franchises, Animal Crossing has been around for a couple decades, but the latest edition has broken sales records since its March 20 release.

It’s also been dominating the down time of Allegra Frank, Vox culture editor and co-host of the gaming podcast “The Polygon Show,” and a longtime Animal Crossing fan. In the six weeks after New Horizons was released, she clocked more than 125 hours on the game.

“Which, compared to a lot of my friends, is actually not that much,” she says, “but for me it certainly is.”

The primary goal of Animal Crossing is to build a community on a deserted island. Players can spend their days collecting rare fish and fossils to build an island museum, or plant dozens of fruit trees to encourage visitors. Like RollerCoaster Tycoon, the charming island life simulator keeps the stakes low and encourages creativity. The newest installment also features multiplayer mode, where people can travel to other islands to trade resources, get inspiration for their own town layout, or just hang out.

Minus an officiant and the paperwork, some people have hosted wedding ceremonies on Animal Crossing, dressing their avatars in formal wear and relaying vows via speech bubbles. Others have used the platform to gather friends for parties or an island-wide game of hide and seek. People have even interacted with celebrities or elected officials. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., an active Animal Crossing player, delivered on May 8 what she called her “first ever commencement address” at a small virtual ceremony for a graduate from Tulane University in New Orleans.

But even without multiplayer mode, these games act as a social buoy by offering something novel to talk about.

“I will send pictures of my Animal Crossing islands to my friends, even if we’re not playing together, and we’ll compare notes,” says Ms. Frank. “So games that aren’t multiplayer can still be social. And I think that’s also a really important part of why these games are so pleasurable right now.”

The stereotype of an antisocial basement-dweller addicted to violent games is fading, and it definitely doesn’t compute with Ms. Frank’s Animal Crossing experience. And as the video game industry expands, different types of games and players are becoming more visible.

“I talk to my parents and I tell them, I think you would like Animal Crossing. It’s so chill and cute. It has great music and funny writing,” says Ms. Frank. “And they’re not totally shocked to hear me say that.”

But Animal Crossing is an investment – the game and the device it runs on are expensive and can be difficult to find. For beginners seeking an easy on-ramp into the video game world, Ms. Frank recommends Neko Atsume, a free mobile app where players take care of stray cats. The Untitled Goose Game is another popular option available on Mac and PC via Steam, a free-to-download gaming software that I use for RollerCoaster Tycoon. The game lets you play as a terrible goose wreaking havoc on a British town. There are puzzles to complete – pull the groundskeeper’s rake into the lake, trap the boy in the phone booth, steal the man’s slippers – but they don’t take too much time or controller savvy.

“For people who are new to this, but want something to do right now that’s sweet, easy, and simple, those are my two,” she says.

And of course, you could try moonlighting as a roller coaster mogul.

Problem solving and socializing, as much as childhood nostalgia, have certainly been a part of my gaming experience. All my park’s challenges, from escaped birds to deadly waterslides, I tackled with the help – or at least commiseration – of my brother, friends, and partner. That’s why I’m sticking with RollerCoaster Tycoon.

At least until the real world becomes a little sweeter, easier, simpler.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Justice for George Floyd, one trial at a time

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Keith Ellison, the lead prosecutor in the case involving the death of George Floyd, is choosing his words carefully these days. He says he seeks no rush to judgment against Derek Chauvin, the former Minneapolis police officer charged with the homicide. He wants the trial to be fair “to all parties.” He says he simply wants the “facts and the law” to prevail.

In other words, justice in the case will be individual. It will not be directed at a group, such as white policemen. Any punishment will be solely for an unlawful act, not a racist motive.

His approach sends a message to protesters attacking police buildings or other government buildings. The justice system must judge individuals on their acts, treating them without dehumanizing stereotypes – even if they treated their victims with dehumanizing stereotypes. Black protesters who fear they or their loved ones might be the next victim of police deserve to have that message made loud and clear.

In a trial, society does not seek broad-brush solutions but individual justice – truth-telling and accountability. The best answer to the inequality of police brutality is the practice of equal justice for all.

Justice for George Floyd, one trial at a time

Keith Ellison, Minnesota’s attorney general and now lead prosecutor in the case involving the death of George Floyd, is choosing his words carefully these days. He says he seeks no rush to judgment against Derek Chauvin, the former Minneapolis police officer charged with the homicide. He wants the trial to be fair “to all parties.” He pleads for patience from protesters seeking a swift conviction. The trial could take months. He says he simply wants the “facts and the law” to prevail.

In other words, justice in the case will be individual. It will not be directed at a group, such as white policemen, or at a class, such as a wealthy establishment. Any punishment will be solely for an unlawful act, not a racist motive.

Inside the courtroom, Mr. Ellison will not be seeking systemic change or social justice. He merely wants, as he says, “the highest level of accountability” for Mr. Floyd’s death. Winning the case would be enough because, he says, too many other trials for alleged police brutality in the United States have not resulted in convictions.

His approach sends a message to protesters attacking police buildings or other government buildings. The justice system must judge individuals on their acts, treating them without dehumanizing stereotypes – even if they treated their victims with dehumanizing stereotypes. Black protesters who fear they or their loved ones might be the next victim of police deserve to have that message made loud and clear.

The former Democratic congressman is not against systemic reform. He seeks to diminish the power of Minneapolis’ police union. He supports a bill in Congress that would require federal officers to use force only when necessary to prevent imminent death or serious bodily injury.

In a trial, however, society does not seek broad-brush solutions but individual justice – truth-telling and accountability. The best answer to the inequality of police brutality is the practice of equal justice for all.

Law, fairly administered to each individual, is not the enemy of social justice. Rather, it ensures that individual rights remain at the heart of ending group inequities.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

It’s time to elevate the human race

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Barbara Vining

There is a crying need for all of us to get to know and truly value men and women of all races as our brothers and sisters in God’s family, in order to heal the wounds of injustice. Each of us is capable of expressing God’s universal, healing love through active compassion and caring.

It’s time to elevate the human race

Important strides have been made toward improving race relations in the United States in the 50-plus years since the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. And there is certainly cause to celebrate progress made in appreciating cultural differences and diversity. But it is sadly obvious that deeply held negative feelings still divide the races. One only has to consider the frequent violence erupting between law enforcement and the black community to realize that the time has come to elevate the human race above the ignorance, injustice, fear, and hatred perpetuated by the long-held belief that we are inherently divided by skin color.

There is something each of us can do – individually, and collectively – by making a decision today that Dr. King, a deeply Christian man, made. He said: “I have decided to stick with love. Hate is too great a burden to bear.”

Hatred springs from ignorance of those we don’t truly know, fear that arises from the unknown, and injustices that have been perpetrated on innocent people. These can be burdens indeed. So, it’s time to “stick with love” – with the courage to have our ignorance, our unjust thoughts and actions, and our fears uncovered and overcome by divine Love, which forgives and heals. In doing so, we can do our part in helping to lift racial prejudice.

The Jan. 10, 1901, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel published an article regarding the building of a monument to the Jewish philanthropists Baron and Baroness de Hirsch “in commemoration of the eradication of racial prejudice.” It contained a letter by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, that was later published in her book “The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany.” In it she said, “Love for mankind is the elevator of the human race; it demonstrates Truth and reflects divine Love” (p. 288).

“Love for mankind.” That’s where we need to start. This involves demonstrating Truth and reflecting divine Love, which is spiritual and universal – so it’s much more than a human emotion. It means elevating our thoughts above defining one another by physical characteristics, and realizing instead that we have one common creator: God, divine Truth and Love, who created us as His spiritual image – one race, that has nothing to do with skin color or human heritage.

This is where we begin to truly know one another. But this understanding also needs to be made practical. And the first step in healing racial divides is to care enough for one another to recognize the challenges and mental wounds that have built up through time, and that pose as barriers to overcoming fears, misconceptions, and injustices. There is a crying need for all of us to get to know and truly value our brothers and sisters of all colors – both spiritually and humanly – and to heal the wounds of injustice through the love that reflects the unchanging love of God.

If progress in elevating humanity seems exceedingly slow, we can take heart from this statement from Mrs. Eddy: “An improved belief is one step out of error, and aids in taking the next step and in understanding the situation in Christian Science” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 296). The situation is understood in Christian Science in proportion as we learn, through step-by-step Christly caring, how to love and value each person as a member of God’s universal family.

Christian Science places the responsibility on all who study it to put into action what they are learning about the universal truth of man and woman made in God’s likeness. We need to let divine Truth inform us that as children of one common Parent, divine Love, we share inherent goodness and purity with all. We need to open our hearts to understand what needs healing in others’ hearts and minds – and to let divine Love move us to repent of unjust thoughts and actions, remove our ignorance and fears, reform our own hearts and minds, and lead us to dialogue and actions that heal. This humble approach is a living prayer that reflects the love that “worketh no ill to his neighbour” and is “the fulfilling of the law” (Romans 13:10).

All humanity is in need of being elevated to that love for others that demonstrates Truth, is just toward everyone, reflects God’s pure love, and brings healing to hearts. In proportion as this is done – through genuine caring and active compassion – the elevation of the human race beyond racial division and strife is accelerated.

Adapted from an editorial published in the Jan. 16, 2017, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

May I take your order?

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’ve got a story about service to the country – and why some want mission-oriented youth programs to have the same status as military service.

Want to stay on top of breaking news? Here’s a window on some of the faster-moving headline news that we’re following.