- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- As nation reels, Trump’s focus is strength, not unity

- Love of country: US ready for mandatory national service?

- Trump and the (not so new) battle over government oversight

- Face masks unleash creativity: ‘You can be part of the bigger story’

- Will the wolf survive? Battle over ‘los lobos’ heats up Southwest.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Why a white, Canadian hockey star is speaking up

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

It seems that Jonathan Toews surprised even himself. In the opening lines of his Instagram post, the white, Canadian hockey star acknowledged that his first reaction to the recent riots across the United States was that they were a “terrible response” to the death of George Floyd.

But then he links to a video of two black men arguing about how the African American community should respond. “They are lost, they are in pain. They strived for a better future but as they get older they realize their efforts may be futile. They don’t know the answer of how to solve this problem for the next generation of black women and men. This breaks my heart.”

The post is more than just one athlete’s musings. For years, black athletes have implored their white colleagues to raise their voices on racial issues – to see through their eyes. Now, that has begun to happen, from Heisman Trophy winner Joe Burrow to Indianapolis Colts head coach Frank Reich – who didn’t start a recent team meeting until players had time to talk about the situation. “Few things stir the human heart and soul like injustice,” he said to the media.

In a long tweet, Philadelphia Eagles quarterback Carson Wentz confessed, “Can’t even fathom what the black community has to endure on a daily basis.”

Former teammate Torrey Smith, an African American, noticed and responded. “You didn’t have to say a thing but you did! Love you bro!”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

As nation reels, Trump’s focus is strength, not unity

Beset by an unprecedented series of crises – from the pandemic and economic catastrophe to unrest over racial disparity – President Donald Trump has made little effort to strike a note of healing.

-

Noah Robertson Staff writer

After days of looting and mayhem in cities around the country, Tuesday night’s protests were largely peaceful. But the nation remains on edge, with President Donald Trump struggling to get his bearings amid multiple profound challenges.

Mr. Trump has largely eschewed the more traditional forms of unity-building. Instead, he has sought to reinforce his image as a “law and order” president, with tough talk and threats to deploy federal troops across the country. With his job approval numbers sagging enough to endanger reelection, Mr. Trump is doing what he knows best: going on the offensive.

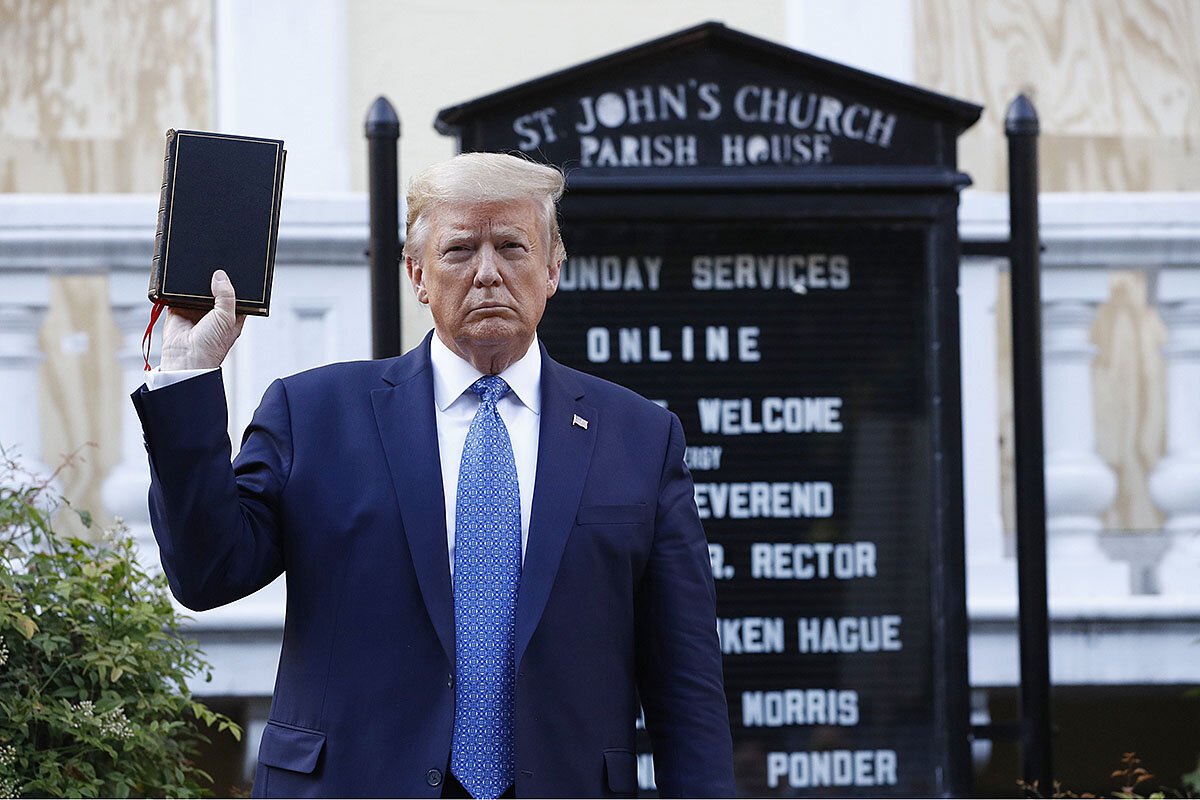

Perhaps the most brazen moment so far of this extraordinary period came Monday, when federal law enforcement officers used chemical sprays to clear peaceful protesters from Lafayette Park, across from the White House, so that Mr. Trump could walk over to historic St. John’s Church. The church’s basement had been briefly set ablaze the night before, and Mr. Trump’s decision to pose outside it while holding up a Bible was widely decried as tone-deaf.

“His only strategy is to disrupt, and anything he can disrupt he will,” says Shirley Anne Warshaw, a presidential scholar at Gettysburg College in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

As nation reels, Trump’s focus is strength, not unity

“This American carnage stops right here and stops right now,” President Donald Trump famously asserted at his 2017 inauguration.

Mothers and children are “trapped in poverty in our inner cities,” rusted-out factories are “scattered like tombstones,” crime and gangs and drugs have “stolen too many lives,” the new president darkly intoned, eschewing the call to unity that is the usual hallmark of an inaugural address.

At a moment of relative peace and prosperity – the nation was already years into a historic period of economic recovery – the dystopian image seemed jarring to many. Still, the speech was classic Trump, fitting for a man elected to shake up a system that had alienated far too many Americans.

Today, however, his words have the feel of foreshadowing for a United States laid low by pandemic, economic catastrophe, and massive social unrest over racial disparity.

To be sure, no one could have predicted what was to come in 2020 – not least President Trump himself – just months before the nation decides whether to give him four more years. The pandemic, in particular, knows no politics or boundaries. But in his response to the events that have transpired, Mr. Trump has set himself apart in the pantheon of American presidents for his seeming unwillingness even to try to unite a nation in distress.

Gen. James Mattis, Mr. Trump’s former Defense secretary, denounced the president’s approach in a statement published Wednesday by the Atlantic magazine. “Donald Trump is the first president in my lifetime who does not try to unite the American people – does not even pretend to try,” wrote General Mattis. “Instead, he tries to divide us.”

“Law and order” president

Past presidents, even controversial ones like Richard Nixon, “tried to put on a good face” in moments of national or international strife, says David Greenberg, a historian at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey. But “there’s a sense in America right now, more than any time I can remember, of just things falling apart and an absence of leadership in the White House,” he adds.

Mr. Trump has voiced sympathy for George Floyd, the black man whose death in Minneapolis police custody last week sparked nationwide protests and lawlessness. The president spoke of the Floyd tragedy at length in remarks last weekend after the successful SpaceX launch.

But Mr. Trump has not engaged in the more traditional forms of unity-building, such as an address to the nation. Instead, he has sought to reinforce his image as a “law and order” president, flooding the Twitterverse with tough talk and threatening to deploy federal troops across the country after berating “weak” governors for failing to control the streets.

Defense Secretary Mark Esper broke with Mr. Trump Wednesday and said that he does not support invoking the Insurrection Act, a rarely used 1807 statute that the president could use to deploy active-duty troops on American soil. But he left open the possibility that such forces could be deployed if the situation grew worse, “as a matter of last resort and only in the most urgent and dire situations.”

Perhaps the most brazen moment so far of this extraordinary period came Monday, when federal law enforcement officers swept through Lafayette Park, across Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House, using rubber pellets and chemical sprays to clear away largely peaceful protesters.

The reason: Mr. Trump’s decision to walk to historic St. John’s Church, located on the far side of the park, and hold up a Bible. The church’s basement had been briefly set ablaze the night before, a moment of horror captured on live television. Though applauded by his supporters, the visit was widely decried by many others – including church leaders – as a tone-deaf photo op that featured a lineup of top aides who are all white.

But actions such as the aggressive clearing of Lafayette Park, which was reportedly ordered by Attorney General William Barr, are in keeping with the president’s style.

“His only strategy is to disrupt, and anything he can disrupt he will,” says Shirley Anne Warshaw, a presidential scholar at Gettysburg College in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

After looting and mayhem in cities around the country on Monday night, Tuesday night’s protests were largely peaceful. But the nation remains on edge, with a president struggling to get his bearings amid multiple profound challenges, any of which on its own would try a chief executive.

His presidency at a critical juncture, with job approval numbers sagging enough to endanger reelection, Mr. Trump is doing what he knows best: going on the offensive.

For Mr. Trump, a big fear is appearing weak, say political analysts and those who know him. When reports came out that the Secret Service had briefly moved him Friday night to the bunker under the White House, as protests flared outside, a thousand unflattering memes were launched. On Wednesday, the president denied that he went to the bunker to protect his safety but rather said he was there to do “a short inspection.”

Sometimes Mr. Trump’s efforts to appear strong end up backfiring. Last Friday, when he tweeted “looting leads to shooting” and warned that “vicious dogs” would greet any protesters who breach the White House fence, he – whether intentionally or not – conjured painful images of the civil rights era and before that, slavery. The “looting-shooting” comment echoed the words of Miami’s aggressive police chief in 1967. Dogs were deployed to attack black protesters in the 1960s, and before that, slaves.

In the eyes of Florida Democratic Rep. Val Demings, an African American and former Orlando police chief who is on presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden's short list for a running mate, the president’s incendiary tweeting amounts to “walking around with gasoline.”

But he’s remained undaunted in his use of Twitter, issuing a flood of tweets defending his record on race.

“My Admin has done more for the Black Community than any President since Abraham Lincoln,” begins a tweet from Tuesday pinned at the top of his account.

A projection of strength

The pandemic has shattered the Trump economy, until recently his strongest argument for reelection. Though strongly Democratic, the African American vote had been seen as fertile ground by the Trump campaign, with hopes of peeling off just enough black voters in key states to keep Mr. Biden at bay.

Now, Mr. Trump is doubling down on law and order. His threat to use the Insurrection Act, though apparently now receding as a possibility, has renewed discussion about how he relates to the states within the American federalist system. Mr. Trump often defers responsibility to governors, such as in the acquisition of medical supplies to fight the coronavirus, but also projects power by threatening the use of an old law that would boost his image of strength.

“There’s a reason we don’t send our federal troops internally,” says Thaddeus Hoffmeister, a law professor at the University of Dayton. “Only in extreme cases do you want one person in control of everything.”

In most of the incidents in the 1960s when the act was invoked, the governors had requested help. “That’s not the case here,” he says.

Professor Hoffmeister suggests there may be rhetorical value for the president in labeling the unrest an “insurrection,” but “I don’t recall an insurrection where law enforcement actually takes knees with so-called insurrectionists.”

William Banks, a professor emeritus of law at Syracuse University, says Mr. Trump has the right to invoke the law, but notes that it was envisioned for a much larger threat than what we’re seeing now.

“You want to come to the aid of the states when states can’t take care of themselves,” he says.

By threatening to invoke the act, Mr. Trump is trying not to appear weak during a domestic crisis, says Professor Banks. But at the same time, he adds, past uses of the law have been unpopular, and governors in crisis-ridden states today might welcome having Mr. Trump seize the spotlight – and take on any blame.

The danger for Mr. Trump, as he surveys a nation under siege from many directions, is that he may look increasingly small.

“The fact that he stopped having the daily briefings is a very good example of his shrinking presidency,” says George Edwards, a presidential scholar at Texas A&M University. “He has nothing to say – no proposals, no empathy.”

Still, despite everything, it’s far too early to discount Mr. Trump’s chances of winning reelection.

Trump biographer Gwenda Blair is reminded of Mr. Trump’s period of intense acquisition in the 1980s, when he took on a giant yacht, a football team, an airline, the Plaza Hotel, and three casinos in Atlantic City.

“It was all in pursuit of making that brand as big as possible, a juggernaut, and he’d be able to ride over anything,” Ms. Blair says.

By the end of the decade, Mr. Trump was headed for multiple rounds of corporate bankruptcy. But with the help of the banks, he still came out on top.

“It worked,” Ms. Blair says. “You tell people what they want to hear, and they’ll follow you.”

A deeper look

Love of country: US ready for mandatory national service?

Mandatory national service has been raised – and rejected – throughout American history. Now a commission wants to expand non-military service as a civic-inspired way to improve lives.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 11 Min. )

In 1906, the philosopher William James called for America to create a “moral equivalent of war,” programs that would rally the country to greatness and a shared sense of purpose. The solution, he said, is mandatory national service.

The impulse lies at the center of a highly anticipated “grand strategy” put forward in March by the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service. Created by Congress, the commission argues that national service – funded by the federal government – is central to improving Americans’ quality of life, bolstering national security, and strengthening democracy.

Despite high demand, service opportunities for young people through AmeriCorps, the Peace Corps, and other programs have long remained static and require a new level of investment, commissioners concluded. They recommend that lawmakers increase federal funding to boost the number of young people working in national service jobs – from 80,000 today to 1 million by 2031.

It comes with hurdles, but advocates believe the pandemic has only underscored the importance of such mission-oriented work.

“We’ve been prepared as a country for a terrorist attack or an overseas war,” says Emma Moore, analyst at the Center for a New American Security. “But clearly we haven’t been prepared – culturally or institutionally – for something like this.”

Love of country: US ready for mandatory national service?

When Xavier Jennings was a teenager, money was tight for his single mother, who had five children, and he felt a duty to help out. He applied for jobs at Walmart and McDonald’s, but struggled to be what he calls in hindsight “interview ready.” He started stealing food from a supermarket, and escalated to selling marijuana on the street.

Still, he liked his high school classes and wanted to graduate, even as evictions and spates of homelessness for his family meant switching schools six times in four years. He was devastated when he fell short of credits. “My idea of success was attached to finishing my education.” He felt, he says, like a failure.

Mr. Jennings drifted further toward drug sales, but his older brother pulled him back when he saw him hanging out with the wrong crowd. “He told people he knew [in gangs] to stay away from me,” Mr. Jennings says. “I owe a lot to him – he really saw goodness in me.”

To redirect him, his brother eventually took him to Mile High Youth Corps in Denver, a branch of YouthBuild, a national nonprofit that helps volunteers earn their GED diplomas and pays them minimum wage to work in construction and conservation. As early as the first day on the job, he started to feel differently about himself, he says. “It was planting the seeds of ‘I can make a difference.’”

Today Mr. Jennings has a full-time job as a YouthBuild program coordinator, mentoring young adults while coaching Little League and finishing up his college degree in nonprofit management.

Getting more Americans like Mr. Jennings to serve their country lies at the center of a highly anticipated “grand strategy” put forward in March by the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service. Created by Congress, the commission argues that national service – funded by the federal government – is central to improving Americans’ quality of life, bolstering national security, and strengthening democracy.

While the commission made headlines this spring for recommending that women be required to register for the draft alongside men, it also stressed the need to elevate the status of national service – giving it the same prestige that military recruits enjoy.

To figure out how to do that, the commissioners took a yearlong Alexis de Tocqueville-like journey across the United States, gathering stories such as Mr. Jennings’ in hundreds of hours of testimony. Their conclusions came with a warning: Despite high demand, service opportunities for young people through AmeriCorps, the Peace Corps, and other programs such as YouthBuild have long remained static and require a new level of investment. The report recommends that lawmakers increase federal funding to boost the number of young people working in national service jobs from 80,000 today to 1 million by 2031.

It comes with hurdles, but advocates believe the coronavirus pandemic has only underscored the importance of such mission-oriented work.

“We’ve been prepared as a country for a terrorist attack or an overseas war, but clearly we haven’t been prepared – culturally or institutionally – for something like this,” says Emma Moore, analyst for the military, veterans, and society program at the Center for a New American Security, a Washington think tank. “It highlights in my mind the greater need for national service.”

Adds retired Navy Capt. Steven Barney, a commissioner and a former general counsel for the Senate Armed Services Committee: “This is the answer to how we mobilize for something like a pandemic.”

“Healthier sympathies”

Back in 1906, the philosopher William James, brother of Henry, called for America to create a “moral equivalent of war” through programs of national service that would rally the country to greatness and a shared sense of purpose.

He admitted that it’s hard to beat battlefields for this. “Militarism is the great preserver of our ideals of hardihood,” he wrote in a widely celebrated essay. Those less martially inclined need to acknowledge the appeal of self-sacrifice and camaraderie forged in combat, he advised, and come up with something able to compete with the “dread hammer” of militarism as the “welder of men into cohesive states.”

The solution, he said, is mandatory national service. “To coal and iron mines, to freight trains, to fishing fleets in December, to dishwashing, clothes-washing, and window-washing, to road-building and tunnel-making, to foundries and stoke-holes, and to the frames of skyscrapers, would our gilded youths be drafted off, according to their choice, to get the childishness knocked out of them, and to come back into society with healthier sympathies and soberer ideas,” he wrote. He also observed, “The martial type of character can be bred without war.”

The idea of mandatory national service has been raised – and ultimately rejected – as a possibility throughout American history. Just a couple of decades before James’ treatise, in 1888, Edward Bellamy published the wildly popular “Looking Backward,” a Utopian novel that was only outsold in its day by “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and “Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ.” Written in the wake of the depression of 1873-79 and a series of recessions in the 1880s, the book called for mandatory service for men and women ages 21 to 45. Some 165 subsequent “Bellamy clubs” sprang up nationwide. The Russian translation of the book was banned by czarist censors for its socialist leanings.

In later decades, philosophers, policy analysts, and politicians offered their own proposals for a “moral equivalent of war.” The New Deal yielded the Civilian Conservation Corps, which mobilized, with the leadership of a young George Marshall, 3 million unemployed Americans who planted some 3 billion trees and constructed 97,000 miles of fire roads, among other projects, between 1933 and 1942, notes a November report by the Brookings Institution.

Following the success of the Peace Corps, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara pushed to tie civilian service to the draft in the early 1960s. Anthropologist Margaret Mead advocated a service program that “would replace for girls, even more than for boys, marriage as the route away from the parental home,” according to a 2019 report from the libertarian Cato Institute. When he was governor of Arkansas and a member of the Democratic Leadership Council, Bill Clinton called for a national Citizen Corps of 800,000 young people. During his presidency, his administration ultimately created the more modestly sized Corporation for National and Community Service and AmeriCorps.

Most recently, retired Gen. Stanley McChrystal, former commander of U.S. forces in Afghanistan, extolled the virtues of universal – though not mandatory – national service. He imagined an America in which “one full quarter of an age cohort, serving together to solve problems, will build attachment to community and country, understanding among people who might otherwise be skeptical of one another and a new generation of leaders who can get things done. I saw these effects for 34 years in the U.S. Army,” he wrote. “We need them in civilian life.”

Social cohesion

The national commission on military and public service, too, set out to answer the question of whether national service should be mandatory for young adults, and ultimately declined to recommend taking this step. Few leaders are fond of working with conscripts who might turn out to be surly, particularly when kicking them out is tough to do.

“Policymakers should make every effort to promote voluntary approaches to service, reserving mandatory service as a last resort only in response to national emergencies and to ensure common defense,” the commission concluded.

Yet a growing number of countries have been adopting mandatory national service for young people. France last year launched a program championed by President Emmanuel Macron that will ultimately train some 800,000 teenagers a year. The aim is to strengthen social cohesion in a country that abolished mandatory military service more than 20 years ago, in 1997, and give young people “causes to defend and battles to fight in the social, environmental, and cultural domains,” Mr. Macron said.

For one month, 16-year-olds will live communally and give up their cellphones to learn first aid, map reading, and emergency response. After dinner each evening, they’ll be encouraged to debate social issues, such as gender discrimination and the roots of radicalization. Then they’ll have the chance to use their skills in volunteer jobs. The program will soon be written into the constitution and become mandatory over the next seven years. It is expected to cost $1.8 billion a year to run.

After abolishing a year of compulsory military service for men in 2011, Germany is now mulling the idea of bringing back a year of mandatory national service as well, in part to address chronic staff shortages in nursing homes and hospices. It would also be required for all adult asylum-seekers, as a way to better integrate migrants, say officials who point to an increasingly polarized society.

In the U.S., demand for government-sponsored volunteer jobs consistently outpaces the number of open slots. After 9/11, there were more than 150,000 requests for applications to the Peace Corps, for example, but only 7,000 positions available, notes the Brookings Institution report. That trend has continued, with the Peace Corps estimating that, on average, there are three to five times as many applications as slots available. These trends have been mirrored in AmeriCorps applications over the past decade, with three to five applicants for every one open position.

The programs seem to have a good effect on those who do get in. AmeriCorps surveys indicate that more than 80% of the program’s national service alumni credit their experience with making them more likely to attain a college degree, vote, volunteer, care about community issues, and fashion practical solutions to problems, the Brookings report says.

Yet expanding such programs is expensive. Convincing Congress to fund them, particularly given the cost of stimulus programs in the wake of the coronavirus epidemic, will likely prove difficult.

While the call to “serve your country” still means joining the military in the minds of many Americans, some 70% of 18- to 24-year-olds don’t meet eligibility standards. Sharell Harmon, for her part, longed to enlist in the Air Force. But when she didn’t qualify, she applied to YouthBuild in Elkins, West Virginia, instead.

The orientation was heavy on trust-building exercises. A black woman in a predominantly white rural area, she wasn’t surprised that her teammates were mostly “guys who wear hunting gear on the back roads, living their best life.” What she didn’t foresee was that they’d become her “brothers” – the sort of battle buddies she’d once hoped to find in the armed forces. “They’re in my everyday,” she says. “We check in. They’re having kids now – we’re family. I didn’t qualify for the military, but it’s important to keep that structure, that support for folks, that possibility of service.”

The commissioners agreed, concluding that the concept of service must not only be “demilitarized,” but also better linked to government. Their recommendations include, among other things, creating a position on the National Security Council to coordinate military and civilian service, and adding slots in U.S. military academies for those interested in civilian government work. Studying and training together, the commission notes, could improve “whole of government” approaches to crises like the current coronavirus.

These steps could also spur the creation of a national database of volunteers that can be cross-referenced with the skills they bring to any crisis, “rather than just calling for them on Twitter,” Ms. Moore adds.

Revamping civics education

Prior to his time on Capitol Hill, serving on the Senate Armed Services Committee and as a staffer for the late Sen. John McCain, Mr. Barney was a Navy lawyer for 22 years. Though he was aware of national service, he still didn’t fully understand what it was, he says. To help remedy this, he and his fellow commissioners traveled to 22 states to ask: Why do or don’t you serve, and what are the obstacles to serving?

In many cases, the answer to that last query, they discovered, was financial. While military service comes with a salary as well as free health care and college tuition, government-backed volunteer programs such as AmeriCorps are less financially liberal. Designed to be intentionally modest, living allowances are often so low that “members cannot sustain themselves without outside assistance,” the commission’s report notes.

When Mr. Barney spoke at a kickoff event last spring for AmeriCorps in Boston, he was surprised to learn that the group’s initial training included a tutorial on how to register for food stamps. Many volunteers who skipped this step acknowledged that the only reason they could participate in the program is that they had family willing to support them. In 2018, the average budgeted living allowance for full-time AmeriCorps volunteers was $15,370.

If volunteers can manage to make ends meet, however, they often come away with valuable skills. Before Maya Gonzalez discovered Mile High Youth Corps in Denver, she wasn’t earning enough working in construction to support her wife and stepchildren. But there were opportunities in energy conservation, program coordinators told her.

“I didn’t know or care much about energy efficiency,” she says. “But they said, ‘You should look into it.’” She did, and through the program became an expert in LED lightbulbs and water-efficient toilets. “I didn’t know toilets mattered,” but by replacing an old model using upward of 1.6 gallons per flush with a new one using half that amount, “You can only imagine how much that saved on water bills,” she says.

What Ms. Gonzalez particularly loved was working with low-income residents. “I’m this Hispanic girl with tattoos – I grew up in the projects – and right away they get the sense I come from a certain background,” she says. “One client told me, ‘I love that it’s you walking in. You feel my pain.’ And, OK, that’s kind of stereotypical, but I’m glad they know they’re not getting judged. All of a sudden they’re making you breakfast while you change a lightbulb.”

Keeping volunteers in their own communities is ideal, says Mr. Barney, who, along with fellow commissioners, recommends creating federally funded fellowships. Under these, people interested in national service would be given a card they could take to any organization and say, “I’m here to help you, and this gives you everything you need to bring me on board.” This might help locals pinpoint sources of need in their neighborhoods.

Better civics education is key, too, the report stresses, since it teaches students how Americans have worked in the past for positive, fundamental change – and overcome efforts to thwart it. As the commissioners traveled the country, “nearly every conversation included a passionate call to improve civic education,” the report points out, noting that the federal government spends more than $3.2 billion for science, technology, engineering, and math programs, versus about $5 million annually on civics.

A handful of states has revamped these courses in ways that could serve as a model for the country. Illinois now requires classroom discussions of “current and controversial events,” and also encourages some volunteering. Florida law mandates that all middle schoolers get one semester of civics, and Massachusetts calls for its high schoolers to take part in at least one “nonpartisan” civics project.

“You need to have service learning opportunities, starting in kindergarten,” Mr. Barney says. “Our vision is that by the time a person graduates, someone will ask, ‘What is your plan to serve?’ and they’ll have a ready answer.”

As a mentor, Mr. Jennings helps his students think through such questions. Hearing their stories helps him point them toward a path that’s right for them. He still aches, though, for the friends and family who didn’t qualify, or weren’t chosen, for programs that have altered the course of his life.

“My story isn’t unique – a lot of folks face adversity at a young age. Opportunity,” he adds, “is the fork in the road.”

Trump and the (not so new) battle over government oversight

Everybody wants checks and balances in government. Except, at times, those governing. President Trump’s targeting of inspectors general is an example of why oversight has become harder.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The American battle over government accountability is as old as the Constitution. But obliging the government to control itself has gotten harder, particularly when it comes to oversight of presidents and their administrations. Polarized partisanship accounts for much of the problem. Parties in Congress walk in lockstep with – or against – the president. In the process, they cede more power to the executive branch.

Since early April, President Donald Trump has fired, transferred, or moved to replace five inspectors general or acting IGs, as well as a whistleblower scientist who crossed the president on the coronavirus. They were in high-profile departments such as intelligence and the Pentagon, and they were looking into sensitive matters, such as favoritism, federal spending, and preparedness on the pandemic. One fired inspector general, Michael Atkinson of the intelligence community, received the whistleblower tip that triggered the impeachment inquiry.

“If you want government to be honest, then Congress has to have the right to investigate, inspector generals have to have the right to investigate, whistleblowers have to whistle,” says former Senate historian Don Ritchie. Temptations to abuse power abound in every administration, he notes. They need to be thwarted.

Trump and the (not so new) battle over government oversight

Ask Don Ritchie about the furor over President Donald Trump’s recent targeting of five internal watchdogs from prominent government agencies, and the former Senate historian cites James Madison’s argument for a government with checks and balances.

“If men were angels” there would be no need for government, the Founding Father posed, and if angels ruled, there would be no need for controls on government. Since neither is the case, Madison concluded: “You must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.”

But obliging the government to control itself has gotten harder, particularly when it comes to oversight of presidents and their administrations, say Mr. Ritchie and others inside and outside government.

Polarized partisanship accounts for much of the problem. Parties in Congress walk in lockstep with – or against – the president. In the process, they cede more power to the executive branch.

In May, President Trump’s lawyers sought to strengthen that shift by arguing against certain congressional subpoena power before the Supreme Court. Additionally, the government’s inspectors general – the independent guardians against waste, fraud, and abuse within federal agencies – are in the president’s crosshairs, with little complaint from his party, which controls the Senate.

“If you want government to be honest, then Congress has to have the right to investigate, inspector generals have to have the right to investigate, whistleblowers have to whistle,” says Mr. Ritchie. Temptations to abuse power abound in every administration, he notes. They need to be thwarted.

Congressional response

One of the most recent inspectors general to lose his job, Steve Linick, was fired from his State Department post May 15, reportedly while investigating arms sales to Saudi Arabia and looking into misusing a political appointee for errands for the secretary and his wife. Today he met virtually with lawmakers from the House and Senate, defending the integrity of his work.

Since early April, President Trump has fired, transferred, or moved to replace four other inspectors general or acting IGs, as well as a whistleblower scientist who crossed the president on the coronavirus.

They were in high-profile departments such as intelligence and the Pentagon, and they were looking into sensitive matters, such as favoritism, federal spending, and preparedness on the pandemic. One fired inspector general, Michael Atkinson of the intelligence community, received the whistleblower tip that triggered the impeachment inquiry.

The president nominated a permanent replacement for the acting inspector general at Health and Human Services, Christi Grimm, after she released a report on shortages on coronavirus testing and protective gear; ousted Glenn Fine from acting inspector general at the Pentagon after he was selected to oversee more than $2 trillion in coronavirus spending; and removed the Department of Transportation’s acting Inspector General Mitchell Behm amid reports of favoritism by the department secretary.

Danielle Brian, executive director for the Project on Government Oversight, says she is “increasingly alarmed” that a weak response from Congress is being perceived as a green light for the president to wage “war” on the inspector general system. That produces a “chilling effect” in the IG offices and discourages potential whistleblowers, says Ms. Brian, whose organization describes itself as a non-partisan independent watchdog.

“In a way, it’s really clever of the White House to target this particular universe of offices … because they are uniquely able to ferret out misconduct and corruption, which is why they were created in the first place,” she says.

Watergate legacy

Today’s corps of 74 inspectors general has its roots in reforms following the Watergate scandal, which led to President Nixon’s resignation in 1974. Created by Congress, the posts are meant to be independent, nonpartisan watchdogs inside the government who conduct audits and investigate wrongdoing. People can report tips to them, and IG offices can investigate those tips, make findings, and recommend changes. They report to both the agency head and to Congress.

In recent years, inspectors general have found the armed services lax in reporting sex offenders to the FBI; concluded that the FBI had cause to investigate alleged links between the Trump campaign and Russia (strongly disputed by the president and still being investigated today); and that a troubled solar panel company, Solyndra, misled federal officials and cost taxpayers half a billion dollars during the Obama administration. They have uncovered the torture of post-9/11 detainees, and billions in waste in Afghanistan reconstruction projects.

Ms. Brian calls President Trump’s actions against these agency guardians an unprecedented attack that she believes is not over yet. Critics of the president’s rapid-fire changes describe them as retaliatory, and complain that replacements are political allies of Mr. Trump with conflicts of interest.

Republican Sen. Charles Grassley of Iowa, who has vigorously defended inspectors general and whistleblowers over his long career, wrote to the president demanding he follow the law, requiring a full explanation for the firings. Last week the White House responded, defending the president’s right to remove an inspector general in whom he simply has lost confidence.

Democratic Rep. Gerry Connolly of Virginia, of the House Oversight Committee, says he is not impressed with Senator Grassley’s letter-writing.

“Where’s the firebrand Chuck Grassley who’s the Thor with the hammer protecting the independence of IGs and insisting on oversight and accountability no matter what it takes?” asks Representative Connolly. The congressman has co-written a bill that would further protect inspectors general from undue political influence and retribution by allowing removal only for cause, and by requiring documentation of that to Congress.

Transfer of power

The law allows the president broad discretion, and when it’s unchecked, it’s going to get taken advantage of, says former Rep. Tom Davis, a Virginia Republican who chaired the House oversight committee during the presidency of George W. Bush. The president is well within his rights, he says, but he doesn’t believe the law envisioned retaliatory firings or “these particular cases.” He adds that in his experience, “not all IGs are good.” Indeed, in 2008 Congress added a special council to oversee inspectors general.

But the problem with oversight is bigger than the IG law, says Mr. Davis. “What we’ve seen over the last 20 years is a huge transfer of power from Congress to the executive branch,” he says.

“This has been going on for some time. The president just accelerated it.”

Congressional investigations of the executive branch tend to be highly partisan in divided government – think of the months that Republicans spent investigating the Benghazi attack under President Barack Obama, and of course, the impeachment of President Trump, says Ms. Brian. “For successful oversight, you’ve got to have buy-in from both sides or the public will not see the effort as legitimate,” she says.

She points out that the Obama administration prosecuted more whistleblowers than any other administration. President Obama also fired an inspector general over a sensitive matter saying merely that he lacked confidence in the official. But the hue and cry, including congressional investigation, over that one case held a lesson for the president and that was the last time he did that.

“We have been trying to enhance protection for IGs since the Bush administration. This was a foreseeable problem,” says Ms. Brian.

Conservative values

Ms. Brian says she is working on inspector-general reform legislation with Senator Grassley’s office and reaching out to a few other Republicans in the Senate – the chokepoint of any such reform because of GOP loyalty to the president. The IGs need “guardrails” she says. They need “for-cause” removal protections, and also ways to prevent sidelining of their investigations when they leave their posts; they should not be replaced temporarily by the president’s political allies.

She sees a “glimmer of hope” in the interest of a few other Senate Republicans. And anecdotally, she was pleased that when she appeared as a guest on a recent C-SPAN show, about half of the Republican callers said that firing the inspectors general “was not OK.”

“This is the kind of accountability … in government that is important to conservative values, and it is making more Republicans uncomfortable than we’ve seen before,” she says.

Others are less optimistic, with Mr. Davis predicting that things get worse before they get better, and that more tussles between Congress and the president will end up in court. A Supreme Court ruling against congressional subpoenas of the president’s financial records would “completely upend the ability of Congress to do any meaningful oversight at all,” says Representative Connolly.

Mr. Ritchie suspects that the tightening of the IG system will wait until after the election, when a consensus develops that “something is wrong.” That’s what happened after Watergate.

“I’ve lived through a lot of big scandals,” he says, “and they do tend, in the end, to right themselves.”

Face masks unleash creativity: ‘You can be part of the bigger story’

When life gives you lemons, make lemonade. And when you wear a face mask – well, why not make it a beautiful one? Resourceful artists are adapting to produce, and often donate, stylish options.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Whitney Eulich Correspondent

-

Ryan Lenora Brown Staff writer

Three months ago, in much of the world, face masks were a no-nonsense medical tool. But today, as the pandemic drags on, they’ve become part of daily attire, from the Czech Republic to Sierra Leone. And as more public health officials have recommended face coverings, shortages in vital protective gear have turned citizens, designers, and luxury brands into lifesaving mask-makers – fashionable ones, at that.

COVID-19 has wrought chaos, but also unleashed an international wave of creativity and solidarity as artists adapt. Designs vary, but the underlying ethos is the same: This pandemic is ugly, but we can respond with beauty.

In Mexico, for example, many artists are harnessing the nation’s vibrant culture, and traditional mask designs, to save jobs and keep each other safe. Out-of-work lucha libre wrestlers make masks mimicking sparkly, lace-up ones worn in the ring. Artisans who typically craft wooden or leather masks now print them on fabric. Designer Carla Fernández partnered with a beverage company to produce tens of thousands of masks covered in brilliant images, donated to frontline workers and for sale to the public.

Mexico is “a country of masks,” says Ms. Fernández. “We dance with masks; there’s lucha libre, carnivals, parties. Now we’re using them in different ways.”

Face masks unleash creativity: ‘You can be part of the bigger story’

Pink flamingo masks in Florida. Lucha libre wrestler masks in Mexico City. Futuristic masks on Parisian catwalks and bold prints splashed across Sierra Leonean markets.

Three months ago, in much of the world, face masks were a no-nonsense medical tool. But today, as the pandemic drags on, they’ve become a de rigueur part of daily attire – from DIY superhero masks for kids to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s pantsuit-coordinated silks. As more public health officials have recommended face coverings, shortages in vital protective gear have turned ordinary citizens, fashion designers, and luxury brands into lifesaving mask-makers.

At times, it’s a political act. At times, a gesture of generosity. And increasingly, a fashion statement. COVID-19 has wrought chaos, but also unleashed an international wave of creativity and solidarity. Mask designs vary, but the underlying ethos is the same: This pandemic is ugly, but we can respond with beauty.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

“By wearing a mask you’re indicating that you care about the people around you,” says Valerie Steele, director of The Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York. “It is so easy to include a mask with your ensemble.”

Luxe look

The meaning and look of masks depends largely on where you come from. Western culture is not keen on masks – sometimes associated with thieves, or even beak-like bubonic plague doctor attire – and many European countries ban face coverings.

“Choosing a fashionable mask, color-coordinating it with your outfit, is taking that extra step towards making it seem friendly,” says Dr. Steele. She predicts masks will remain in the Western wardrobe post-pandemic, but less so than in Asia, where they have been common for years to protect against colds and pollution.

Major luxury brands in Europe played good Samaritan during the worst of the crisis, making face masks for health workers and linking mask purchases to charitable donations. Many remain hesitant to chase profits, but other retailers are charging ahead.

French designer Marine Serre proved prescient, featuring masks in her collections since 2019. One even included a high-end air filter. “Fashion is just a translation of what is happening around us,” says Ms. Serre, who found inspiration biking in polluted Paris.

Now, her priority is to make masks that are safe, not just fashionable. “The pandemic has broken an ice wall,” she says. “We can wear masks and it is fine and we can also have fun. Let’s see how the mask evolves with our lives.”

The Czech Republic was one of the first European nations to make masks mandatory, sparking a sewing frenzy. A Facebook group called “Czechia sews face masks” gathered a following of more than 40,000 people, mainly women willing to make free masks for health workers. In some areas, sewers hung up their creations on “mask trees” outside, where anyone in need could take them.

An exhibit at the National Museum in Prague showcased this outburst of solidarity. “People wanted to wear something that is interesting, that is fashionable,” says curator Mira Burianova. Some masks are by local designers, but most are homemade creations quickly stitched together to confront the crisis.

“It is a symbol of this period, but I hope that our children will not need to wear masks,” she adds.

“A country of masks”

Masks in Mexico, meanwhile, reflect a history of creative resilience.

“Mexico is a country of masks,” says designer Carla Fernández. “We dance with masks; there’s lucha libre, carnivals, parties. Now we’re using them in different ways.”

The coronavirus pandemic snuffed festivals and tourism. But many are harnessing the nation’s vibrant culture to save jobs and keep each other safe. Out-of-work wrestlers make masks mimicking sparkly, lace-up ones worn in the ring. The designs of artisans who typically craft traditional wooden or leather masks, such as of animals or devils, are now printed on fabric.

Ms. Fernández worried COVID-19 would hit the nearly 60% of Mexicans in the informal economy especially hard. She teamed up with a beverage company to produce 50,000 masks donated to public transportation workers and medical professionals. More are for sale to the public. The pivot helped keep afloat the 175 artisans and 20 employees she regularly works with, and 25% of all sales go back to the traditional mask-makers whose images are being used.

Even for Ms. Fernández, a well-established designer, finding appropriate fabric and functional patterns was a challenge. But the results are masks covered in brilliant images, like the sharp, triangular-toothed, bright-orange jaguar. She says Mexican adaptability – dating back to indigenous practices mixing with Spanish culture – is evident in how citizens reacted.

“There’s always someone to give you a hand,” says Ms. Fernández, and it’s typically not the government. “Family, friends, and community are a pillar of society. It’s in our blood: If you see a problem, you help.”

Jesús Ortiz shares that instinct. The father of three went to the United States when he was 19 and was deported almost 10 years later, separating him from his family. Lately, he’s spent his Fridays traveling across Mexico City, delivering face masks made by fellow deportees and returnees. “It keeps me busy and it’s a way to help fewer people get exposed,” he says. It also helps counter stereotypes that deportees are criminals or victims.

“It’s really important for deportee and returnee communities to mobilize together because they often don’t have those family safety nets that many Mexicans – and even Mexican public policy – rely on to respond to crises,” says Jill Anderson, co-director of Otros Dreams en Acción (ODA), an organization Mr. Ortiz belongs to, which supports deportees and returnees. Three members make masks covered in cactuses to donate or to sell.

Experts credit a past pandemic in Mexico for its openness to face masks. In 2009, when the H1N1 “swine flu” emerged here, masks were the central measure pushed by the government, not stay-at-home orders, notes urban anthropologist José Ignacio Lanzagorta.

“We’ve assimilated to the use ... little by little,” he says.

Covered, and beautiful

Many African countries, meanwhile, have already made face covers compulsory. And the continent’s designers have responded with masks designed to turn a drab public health protocol into something beautiful.

“I thought, we can find a delicious way to be safe and fashionable at the same time,” says Cape Town designer Tracy Gore, who introduced masks to match her flower print tops and bomber jackets when masks became mandatory in South Africa.

Mask-wearing took root fairly easily across many parts of Africa, thanks in part to a culture of made-to-order fashion, facilitating companies’ pivot toward the latest health accessory.

In Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone, thousands of tailors usually work from tiny studios tucked between barber shops and corner stores, or in clattering rows in the fabric section of markets. When the government began restricting movement and enforcing social distancing measures, customers disappeared. No one needed a new dress for church or a birthday or a wedding.

But Mary Ann KaiKai, who runs a label called Madam Wokie, found purpose and opportunity. Ms. KaiKai had noticed how most of the thousands of women who sold fish, plantains, and neon orange bottles of palm oil in overcrowded markets didn’t wear masks. She rustled up donations, hired 100 out-of-work tailors, and turned her three-story atelier into a mask-making assembly line. Within three weeks, her team had made and distributed 72,000 masks across Freetown.

“Our question was, how do you make something that addresses this need but also is something where people will say, ‘This is colorful, this is vibrant, and I want to keep wearing this because it’s beautiful,’” says Ms. KaiKai, who made luxury clothes before the crisis. The masks she designed are made from ankara, a printed fabric known for its swipes of bright colors and angular geometric patterns.

“Especially with the health system in Sierra Leone being weak, it’s important to protect yourself before you get sick,” she says. “I’m not going to win any fashion awards producing masks. But it’s about how you can be part of the bigger story of defeating this disease.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Will the wolf survive? Battle over ‘los lobos’ heats up Southwest.

Is it ever right to kill a protected species? In New Mexico and Arizona, a 24% increase in Mexican gray wolves is cause for celebration – and consternation.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Melissa Gaskill Correspondent

John Oakleaf is a clandestine matchmaker. He sneaks captive-bred wolf pups into wild dens.

“We go through a lot of effort, rubbing the pups together to make them smell alike,” says Dr. Oakleaf, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “Wolf mothers are pretty good, but fortunately, they can’t count.”

A recent count suggests that those efforts are starting to pay off. In March, Fish and Wildlife announced that it counted at least 163 Mexican gray wolves in New Mexico and Arizona. The very next week, however, the agency authorized the killing of four wolves.

For conservationists, a protected species must be protected – no matter the cost. But the federal government has long taken a more nuanced approach, instituting protections and managing captive breeding programs but also allowing sanctioned killings to remove problem individuals.

The current debate is one more in a long line of regulatory battles that have pit advocates and the Fish and Wildlife Service against each other, though at heart, the two sides have a unified goal.

“We need to get more wolves in the wild, give them the space to roam, and learn to accept them on the landscape,” says environmental attorney Kelly Nokes.

Will the wolf survive? Battle over ‘los lobos’ heats up Southwest.

John Oakleaf has learned to rejoice in small victories.

One such victory came on March 17, when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) announced it counted at least 163 Mexican gray wolves in New Mexico and Arizona. That may not sound like much. And indeed the number is still perilously low. But it also represents a 24% increase over the previous annual count and follows a 12% increase the year before that.

The uptick is a testament to the power of protection under the federal Endangered Species Act, says Dr. Oakleaf, a biologist with FWS.

The very next week, however, the agency authorized the killing of four wolves, a twist that underscores the complexities involved in protecting an apex predator. For conservationists, a protected species must be protected – no matter the cost. But the federal government has long taken a more nuanced approach, instituting protections and managing captive breeding programs but also allowing sanctioned killings to remove problem individuals.

As field coordinator for the Mexican gray wolf recovery program, Dr. Oakleaf and his team have gone to great lengths to bolster the population, including placing captive-bred pups in wild dens.

“We go through a lot of effort, rubbing the pups together to make them smell alike,” he says. “Wolf mothers are pretty good, but fortunately, they can’t count.”

To advocates, lethal removals undermine that painstaking effort and threaten the long-term survival of a species that the government has vowed to protect. For Kelly Nokes, an attorney with the Western Environmental Law Center, the current debate is one more in a long line of regulatory battles that have pit advocates and FWS against each other, though at heart, the two sides have a unified goal.

“We need to get more wolves in the wild, give them the space to roam, and learn to accept them on the landscape,” says Ms. Nokes.

The saga of los lobos, as the Mexican gray wolf is known in Spanish and colloquially, traces a familiar path. It once roamed portions of Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Mexico, but had been nearly wiped out by the 1970s. FWS listed it as endangered in 1976 and brought the seven known remaining lobos into captivity. In 1998, the agency released 11 captive-bred animals in a small area on the Arizona-New Mexico border now known as the Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area.

Conservation groups have repeatedly taken the agency to court, most recently suing over what they say are shortcomings in and discrepancies between a 2015 rule for reintroduction and a recovery plan revised in 2017. Among the reasons cited: The rule sets arbitrary limits on population numbers and range, and the plan departs from the best available science and includes politically motivated obstacles to recovery.

One major point of contention hinges on a population cap of 325 outlined in the 2015 rule.

“Best available science shows that, at minimum, a population of 750 is required for recovery, including three separate populations of at least 250 wolves each,” says Ms. Nokes.

In 2018, a federal judge found that the 2015 rule “fails to further the conservation of the Mexican wolf” and sent it back to the agency for rewriting.

The Fish and Wildlife Service is in the process of adapting that rule, which was based on research into how much space wolves need, to better meet the long-term goals of the most recent recovery plan, says the agency's policy coordinator, Tracy Melbihess.

Ms. Nokes argues that the plan does not address all threats facing the species, as required by the Endangered Species Act. In particular, she says, it has no method to address the population’s lack of genetic diversity.

To conservation groups that have waged these battles for decades, the discussion of lethal removals feels like one more setback on the road to recovery for los lobos.

But to Nelson Shirley, lethal removals are a vital last resort.

Owner of Spur Lake Cattle Co. headquartered in New Mexico, Mr. Shirley says he lost about 120 of his 2,000 cows to wolves last year. Both wolf packs involved in the lethal removals have been on Spur Lake ranches.

“I am not in favor of wiping wolves out, just in favor of removing the wolves actually killing livestock,” he says. “I can only go from my personal experience that when we have been successful in trapping and removing a wolf that has been implicated in depredation, those stop immediately, like flipping a light switch.”

Mr. Shirley employs several nonlethal methods to control wolf depredation, but questions their effectiveness – and their cost.

The focus on cost frustrates wolf advocates. Bryan Bird, southwest program director for Defenders of Wildlife, argues that removing livestock from public land, not wolves, could more effectively reduce depredation.

“Bottom line, this is a hotspot for conflict between wolves and cows,” Mr. Bird says. The Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area is on national forest land.

Ms. Nokes of the Western Environmental Law Center thinks in terms of cost too, costs to the recovery of the Mexican gray wolf.

“The 163 wolves in the wild is definitely a bump up from last year, which we’re really excited about,” she says. “But just think what could happen if we actually aided their recovery instead of hampering it.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Peacemakers rescue the protests

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Three months before George Floyd died under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer, top law enforcement officials in Minnesota recommended a way to reduce such deadly force encounters. They would designate a peacemaker. The position has yet to be created. But the role was amply demonstrated last Monday – by Mr. Floyd’s brother.

Terrence Floyd visited the spot where his brother was killed and addressed the rioting and looting in Minneapolis and dozens of other U.S. cities. “Do this peacefully, please,” he said. He then defined peacemaking as a positive force, not merely the absence of violence.

In many other cities, peacemakers have rushed to deescalate the kind of violence that overtook peaceful protests following the May 25 killing. These violence interrupters may not win the Nobel Peace Prize but surely they deserve credit for bringing restraint and understanding to the protests.

Peacemakers rescue the protests

Three months before George Floyd died under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer, top law enforcement officials in Minnesota recommended a way to reduce such deadly force encounters. They would designate a peacemaker. A state official would mediate disputes and promote healing in communities. The position has yet to be created. But the role was amply demonstrated last Monday – by Mr. Floyd’s brother.

Terrence Floyd visited the spot where his brother was killed and addressed the rioting and looting in Minneapolis and dozens of other U.S. cities. “I understand you’re all upset,” he told a crowd. “Let’s switch it up. Do this peacefully, please.”

He then defined peacemaking as a positive force, not merely the absence of violence. He urged people to channel their anger into educating themselves and using their power at the ballot box. He also led a prayer circle at the site.

In many other cities, peacemakers have rushed to deescalate the kind of violence that overtook peaceful protests following the May 25 killing. These activists range from church clergy in Columbus, Ohio, to former light heavyweight champion Chuck Liddell in Huntington Beach, California.

In New York state, the anti-violence group Buffalo Peacemakers promoted dialogue. A similar group, Cure Violence Global, was active in New York City. During protests Tuesday in Philadelphia, a plane flew over the city pulling a banner reading: “Bless the peacemakers for they shall inherit earth.”

These violence interrupters may not win the Nobel Peace Prize but surely they deserve credit for bringing restraint and understanding to the protests.

Last year, 47 of the world’s 195 nations witnessed a rise in civil unrest, according to the political analysis firm Verisk Maplecroft. In most of them, protesters had to decide whether the use of violent tactics would help or hinder their cause. In Hong Kong, for example, activists are severely divided on this question. The record is clear, however, on which path is better. A 2013 study by scholars Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan found that campaigns of nonviolent resistance were more effective than violent insurgencies from 1900 to 2006.

To activists trying to prevent violence, peace is a verb. “At the center of nonviolence stands the principle of love,” stated Martin Luther King Jr. Out of love for his brother last Monday, Terrence Floyd stood up to protesters using violence and showed that, for many on the streets of Minneapolis and elsewhere, peace really is a verb.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Taking down the real enemy

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Nancy Humphrey Case

It can seem there’s no end to the destructive influences in the world. But the recognition that evil has no legitimacy in God or any of God’s children can shift our thought from focusing on a problem to finding a solution.

Taking down the real enemy

I was intrigued by a recent Monitor article describing how Estonia has developed a comprehensive system for preventing foreign interference in its democracy in the wake of destructive rioting and cyberattacks, evidently orchestrated by Russians, in 2007 (see “Cybersecurity 2020: What Estonia knows about thwarting Russians,” Feb. 4, 2020).

Uncovering whatever deception and manipulation of public thought may be going on is a good first step in combating evil in the world. The discoverer of Christian Science and founder of this news organization, Mary Baker Eddy, encouraged alertness to evil’s attempts to provoke discord while remaining hidden. Using the term “animal magnetism” to refer to the deceptive, mesmerizing nature of evil, she writes: “The mild forms of animal magnetism are disappearing, and its aggressive features are coming to the front. The looms of crime, hidden in the dark recesses of mortal thought, are every hour weaving webs more complicated and subtle” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 102).

The good news is that we are well equipped – even divinely empowered – to counter evil. Based on the Bible, in particular Jesus’ teachings, Christian Science defines God as purely good and supremely powerful, neither creating nor sanctioning evil in any form. God has created everything as spiritual, and sees it as totally good. In one of his parables, Jesus explains evil as coming from “an enemy” in the dark of night, “while men slept” (see Matthew 13).

Exposing evil as having no divine authority or part in God’s creation doesn’t mean ignoring or taking a naive approach to it. On the contrary, it enables us to respond more powerfully, by making a critical distinction between the evil itself and the person or group of people who seem to be giving it life and power. Because if everything God created, including man (meaning each one of us), is actually spiritual and good, then evil is not personal at all. To define it as a person or group is to leave evil still hiding behind a mask, making it look like it has intelligence, power, and influence.

Instead, we can ask, What is the real enemy at the bottom of it all?

In the last chapters of the Bible, the sum total of all evil is epitomized by a great red dragon maliciously intent upon destroying good. In effect, it stands for the notion that there is a power opposed to God, good, and that it can win against God. But the dragon, identified as a deceiver, was “cast out into the earth” (Revelation 12:9) – into dust, nothingness – and the reign of God, or good, was realized.

Here is a model of hope for humanity. Whatever tries to tear us apart, to divide us, to destroy all that is good, to claim that it’s more powerful than God, is a liar. And when it’s exposed as such, it can be proved powerless.

A friend of mine had trouble with a neighbor who was expressing hostility toward him. The situation escalated to the point where it was interfering with my friend’s work. In an effort to restore calm, he was spending so much time analyzing comments and composing emails, it seemed he couldn’t think about anything else.

My friend was also praying, though. And as he did it became clear to him that the root of the problem wasn’t a person needing to be mollified. It was impersonal evil that would fixate his attention on antagonism, so preventing him from doing anything useful.

Recognizing this evil as powerless to stop God’s expression of good in all His children (including the neighbor) brought my friend peace and dominion over being drawn in by the trouble. He was no longer intimidated. This mental victory occurred completely within his own prayer-lighted consciousness. Shortly after, he found an appropriately firm but cordial way to respond to his neighbor, who in turn replied respectfully. The verbal attacks ended.

It’s a small example in the grand scheme of things, but to me it’s encouraging evidence that ultimately, evil has no inherent ability to stop or reverse the activity of good, of Spirit, God, who is infinite and has no legitimate opposite. And the same rule applies to big things. Divine Spirit cannot be divided, torn apart, pulled down, or destroyed. Neither can His creation, His expression of good.

Alertness to destructive influences and their underlying illegitimacy will help us stop being dismayed by evil and instead prove, little by little, the powerlessness of evil and the God-empowered nature of good.

A message of love

Pride and joy

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when Christa Case Bryant looks at the bad actors who are seeking to exploit nationwide protests for their own advantage.