- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- With militias on the rise, states boost vigilance

- The election is in 19 days. The legal battles have already begun.

- Ultimatum signals modest US goal in Iraq: Avoid defeat

- Drive-thru Texas state fair: Fried Oreos, yes. Baby animals, no.

- ‘Chicago 7’: Fast-talking court drama is a window on protest and America

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A lesson in perseverance from my preschooler

Husna Haq

Husna Haq

This fall I got a lesson in perseverance from an unlikely teacher: my 4-year-old son.

After six months away from school nestled in the cozy confines of our home, he was – like more than a few children these days – nervous to return to school this September. OK, he was downright hysterical. Morning drop-offs were grim affairs in which we plastered reassuring smiles on our faces as we pried our howling preschooler’s arms from around our necks, then worried all the way home. By Day Five, I was convinced we’d be dropping a teary teen off to college in 15 years.

But in the calmer moments, we talked. About how bravery isn’t the absence of fear, but of knowing our capabilities, and doing the scary thing anyway. “I know it’s hard for you, but I know you can handle it,” I’d tell my kid as he pushed toy excavators on the ground and pretended not to listen. But he was listening. On Day Six, we were stunned when he gave us a smile behind his favorite yellow mask and walked in to school.

During a year marked by exceptional turmoil with no seeming end in sight, it’s easy to give up hope and give in to fear. But a brave little boy reminded me to keep going – to do the scary thing, have the difficult conversation, sit with discomfort – and to know that in the very act of persevering lies progress.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

With militias on the rise, states boost vigilance

Events in Michigan and beyond bring an uncomfortable question to the fore: Under what authority do private militias operate in America? And at what risk to democracy?

-

Noah Robertson Staff writer

With the arrest of 13 people charged with a domestic-terrorism conspiracy to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, Americans are watching the rule of law put to severe new tests. The rise of private militia groups in recent decades – including a group involved in the Michigan plot – is coinciding with broader political unrest.

Armed and politically engaged civilians are showing up on America’s streets in a year of protests, pandemic, and an already divisive election campaign. States are starting to step up their watch. Oregon police say they have begun to check gun permits at rallies. Michigan has a hotline for poll workers, so law enforcement can respond if poll watchers show up armed.

Nationwide, at least 40 bills and ordinances have been introduced to curb violent protests, though most of those have failed on free speech concerns. Yet all 50 states have bans on paramilitary groups, and authorities in many states are considering new efforts at enforcement.

“The Second Amendment does allow people to associate under arms, but not as a paramilitary unit that is unvetted and does not answer to civilian government,” says Brian Levin, an expert on extremism at California State University, San Bernardino. “The statutes, in essence, prohibit impostering the National Guard.”

With militias on the rise, states boost vigilance

Around the time that Sylvia Santana watched armed men pile into the Michigan Capitol in Lansing to protest pandemic restrictions in April, a plot to attack politicians involving at least one of those men, the FBI says, had begun to hatch.

Tempers were stretched. A seemingly fringe idea transformed into an operation.

Members of a self-constituted militia now envisioned themselves as constitutional law enforcers. They would kidnap and try Gov. Gretchen Whitmer on charges of treason. Or, as one said according to an FBI affidavit, they might just knock on her door and shoot her when she answers.

“This is where the Patriot shows up,” said a deciphered message cited in the affidavit. “Sacrifices his time, money blood sweat and tears.”

Thirteen men from two militia groups are now under arrest, charged with a domestic-terrorism conspiracy in which Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam was mentioned as another target, the FBI confirmed on Tuesday. And onlookers like Ms. Santana see concerns that go beyond this one plot.

“Any threat [on duly elected officials] is a threat to all of us,” says Ms. Santana, a first-term Michigan state senator who says she was left shaken by the news.

Americans, in fact, are watching the rule of law put to severe new tests by the rise of armed and politically engaged civilians on America’s streets in a year of protests, pandemic, and an already divisive election campaign.

Some, like those arrested in the Michigan plot, are members of privately organized militia groups. Others are not. Either way, many experts see a slippery slope along the line from constitutionally protected rights such as gun ownership to political violence that could threaten the nation’s democratic framework.

“The Second Amendment does allow people to associate under arms, but not as a paramilitary unit that is unvetted and does not answer to civilian government,” says Brian Levin, an expert on extremism at California State University, San Bernardino. “The statutes, in essence, prohibit impostering the National Guard.”

“It’s unprecedented” in the U.S.

A recent parade of armed Americans flying flags from a pickup truck convoy in Portland “reminded me of the scenes of ISIS mobilizing in armored columns in Mosul,” says Javed Ali, a Michigan-based former senior director for counterterrorism at the National Security Council.

“And I thought, ‘Wow, this is the United States, and yet we’re seeing something that has the iconography of terrorism overseas.’ It’s unprecedented ... and it’s a real sort of challenge: What is the line between protected activity for U.S. citizens and what’s the line into something that looks like terrorism?”

The search for answers is a difficult one, made even more so by a frustrating pandemic, a polarized electorate goosed by a president chosen in part to disrupt the status quo, and a massive trust deficit where over half of Americans now believe in debunked conspiracies, according to a new bipartisan survey.

Traditionally, a militia is a body of citizens who can be called on when needed as a supplement to formal military forces. Legal scholars widely say that when the U.S. Constitution refers to “well-regulated” militia, it means a group regulated by the state. And all 50 states ban paramilitary groups, though 36 allow open carry of firearms at protests.

Amid lax oversight by law enforcement, private militia groups – untethered to the state but sometimes cultivating ties to local authorities – now have a presence across the nation in several hundred groups by some estimates. Growing since the 1990s, and expanding further after the election of Barack Obama as president during the Great Recession, these groups generally espouse firm views on individual liberty, and skepticism of big government.

The armed groups aren’t necessarily anti-democratic, “because there are different definitions of democracy,” says Vasabjit Banerjee, a Mississippi State University political scientist who studies rural insurgencies in developing countries like India, Mexico, and Colombia. “This idea that militias exist outside of normal politics is actually something that isn’t true.”

In fact, politicians may tacitly tolerate militia or other armed groups. President Donald Trump, when asked in a September debate if he would denounce white supremacists and militia groups, told one right-wing group merely to “stand back and stand by.”

And, while not directed overtly at militias, presidential tweets such as “Liberate Michigan” or “Liberate Virginia” risk being interpreted as calls to action, some experts on extremism say.

Meanwhile, as protests rocked the streets of Kenosha, Wisconsin, amid controversy over a fatal shooting by police, some videos showed police voicing appreciation for a turnout of armed civilians – shortly before one of those civilians killed two people with his rifle.

The test for law enforcement

To Mr. Banerjee, ”the problem that always lies in the delegation [of power to armed auxiliaries] is that the control of the bus slips out of your hand.”

All of that can put law enforcement in a bind as armed people have taken to the streets to protect buildings and confront other protesters, sometimes with lethal results. The Michigan plot also included threats to police officers. An elected Michigan sheriff, meanwhile, has appeared on stage with some of the alleged conspirators, and in recent days broached that they may have been seeking to use legitimate citizens-arrest powers in face of tyrannical leadership.

Acts of far-right domestic terrorism have waxed and waned, partly in sync with political tides, spiking around the 2008 election and again in 2016. Last year was among the most lethal since 1995, when the bombing of an Oklahoma City federal building was carried out by men who by some reports had ties to a Michigan militia. The bulk of last year’s 29 deaths by extremist violence are attributed to white supremacists, according to numbers from the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism.

Violence this year includes what experts say is the first left-wing killing of a protester – in Oregon, in the wake of the truck convoy that troubled Mr. Ali.

“Today, we have a shift where extremists change their activities based on whether they think they are operating in some ways with some kind of relationship to the mainstream – or they’re in an insurgency against it,” says Mr. Levin. “We are in a new era.”

One militia member in Virginia

Many Americans who join militias see the groups as operating within the laws of the land – and in support of the rule of law. Early this year Paul Cangialosi joined the Nelson County Militia just outside Charlottesville, Virginia.

The militia, he says, is 70-strong and has weekly trainings that include first aid, firearm safety, wilderness survival, and military tactics. They often coordinate with other militias with similar goals.

Mr. Cangialosi looks no further than the Virginia Constitution for validation. It states that “a well-regulated militia, composed of the body of the people, is the proper, natural and safe defense of a free state.”

“We’re not trying to have some secret organization that plots to kidnap government officials or plots to overthrow anything,” says Mr. Cangialosi. “We’re behaving in a defensive fashion. Everything we train for is to defend our way of life, not to be aggressors.”

Shunning the anarchist tendencies that he observes in some militia-style groups, he says his focus is on individual liberty. ”I’m anti-intrusive government and I’m anti-big government and I’m anti-overstepping government.”

But parsing whether such groups are bulwarks of American liberty or prospective domestic terrorists is part of the challenge for U.S. leaders and law enforcement, as the Michigan kidnap plot makes clear.

Mr. Cangialosi says the local sheriff doesn’t work with the Nelson County Militia directly, but they do keep in contact about weekly militia training and operations. They also exchange prayers for each other’s families.

For Mr. Cangialosi, the militiaman in Virginia, the Constitution makes the decision about whether government overreach translates to tyranny an individual one.

Right now, “I don’t know what the line in the sand is for most people,” he says. “And I think everybody has to decide that for themselves. I think that’s one of the things that we all try to work through as a group.”

What states are doing

For Mary McCord, the former acting assistant attorney general for national security at the U.S. Department of Justice, the danger to democracy posed by militias is clear.

“A lot of these groups are running around on private property playing army on the weekend, so law enforcement hasn’t really turned their attention to that,” she says. But now, “even if militias aren’t plotting anything as sinister as a kidnapping of a governor, their heavily armed presence on the street without political accountability has had terrible results.”

States are starting to step up their watch. As Americans gird for a contentious and possibly disputed election, Oregon police say they have begun to check gun permits at rallies. In Michigan, Senator Santana is working to increase security at the capitol. The Michigan attorney general has also set up a hotline for poll workers, so law enforcement can respond if poll watchers show up armed.

Ms. McCord, now legal director for the Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection, appeared last week at a press conference in Philadelphia with District Attorney Larry Krasner to warn armed groups that any voter intimidation will be dealt with by law enforcement. She also recently spoke to the Major Cities Chiefs Police Association Convention on the issue.

Nationwide, at least 40 bills and ordinances have been introduced to curb violent protests, though most of those have failed on free speech concerns.

And some politicians are calling for a tempering of a broader challenge – the militancy of public discourse. Republican Sen. Mitt Romney of Utah wrote this week, “The rabid attacks kindle conspiracy mongers who take the small and predictable step from intemperate word to dangerous action.”

Amid the growing vigilance, there are still some potential gray areas, legally, about militias. "No court has ever had to decide whether a group of armed individuals or three guys bearing firearms are doing it under the guise of self-defense or as an unlawful paramilitary organization," Ms. McCord says.

Still, she sees a shift away from apathy about the risk of armed insurgents in America.

“What [police] really should be doing is saying, ‘No, thank you. Your help is unlawful and don’t come here or we’re going to enforce the law.’ But I think law enforcement leaders are starting to get it and understand.”

The election is in 19 days. The legal battles have already begun.

One party wants expansion of the electorate, the other wants to contract it. How that plays out on and around Election Day will be battled by legal teams both presidential campaigns have assembled to challenge how voters’ ballots are cast and counted.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

In the presidential race, hundreds of election law disputes are percolating nationwide. And the pandemic’s disruption of normal voting patterns has intensified a fight over how ballots are cast and which are counted.

Both campaigns have built legal war rooms for Election Day challenges that could go all the way to the Supreme Court. But even if there’s no replay of the razor-thin margins in the 2000 litigation of Bush v. Gore, election law rulings by courts on contested issues like ballot collection and verification could shape the rules for future elections.

The election rules being litigated vary, says Justin Levitt, a former deputy assistant attorney general in the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division under President Barack Obama, noting, “One of the political parties sees its future in the expansion of the electorate and the other party sees its future in the contraction of the electorate.”

This battle has been supercharged by the pandemic and by problems experienced in states that switched to mail-in ballots during primaries and struggled with timely counts. With so many transactions among so many people and in such a charged political atmosphere, “some irregularities are bound to develop,” says Michael Morley, an assistant professor of law at Florida State University, in Tallahassee.

The election is in 19 days. The legal battles have already begun.

Two decades ago, a presidential election was decided by Bush v. Gore, a Supreme Court ruling that put a stop to ballot recounts in Florida and handed victory to George W. Bush by a margin of 537 votes.

That postelection legal battle in 2000 turned on incompletely punched paper ballots and a faulty ballot design in one Florida county.

Now, in the race between President Donald Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden, hundreds of election law disputes are percolating in jurisdictions nationwide. And the pandemic’s disruption of normal voting patterns has intensified a fight over how ballots are cast and which are counted.

In the event of a close margin in a battleground state, some of these cases could prove pivotal. Trailing in the polls, President Trump continues to make claims of systemic fraud by Democrats and refuses to commit to a transition of power if he loses on Nov. 3.

Both campaigns have built legal war rooms to prepare for Election Day challenges that could go all the way to the Supreme Court. But even if there’s no replay of the razor-thin margins in Bush v. Gore, election law rulings by courts on contested issues like ballot collection and verification could shape the rules for future elections.

“Most election litigation contests an election after the election is done,” says Barry Richard, a Tallahassee, Florida, attorney and Mr. Bush’s general counsel in the state in 2000.

Many of these lawsuits are dropped because the number of contested ballots are too few to swing the outcome. “This time it’s different because we’ve got a huge amount of litigation challenging things before the election happens,” he says.

What’s also different, he adds, are repeated attacks on the legitimacy of the election.

“In the past, nobody questioned the integrity of the system. Nobody suggested that the vote was fraudulent or that the election wasn’t fair. It was just a question of how you fix the problem,” says Mr. Richard, who has represented Democratic and Republican candidates in litigation.

Expansion vs. contraction of the electorate

Republicans contend that the rapid expansion of mail-in voting in November’s election opens the door to ballots improperly cast.

“Democrats are working to shred election integrity measures one state at a time, and there’s no question they’ll continue their shenanigans,” Matthew Morgan, the Trump campaign’s general counsel, said in an email. Specifically, suggests the Republican National Committee’s Protect the Vote website, the Democrats are using the pandemic and courts to eliminate election safeguards by legalizing ballot harvesting and implementing a nationwide mail-in ballot system.

Democrats argue that the greater risk is voter disenfranchisement and that postal ballots can be secure, as demonstrated in several states that already hold universal mail-in elections. They accuse Republicans of seeking to suppress turnout by limiting the number of ballot drop boxes, for example.

The election rules being litigated vary, says Justin Levitt, a former deputy assistant attorney general in the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division under President Barack Obama, noting, “One of the political parties sees its future in the expansion of the electorate and the other party sees its future in the contraction of the electorate.”

This battle has been supercharged by the pandemic and by problems experienced in states that switched to mail-in ballots during primaries and struggled with timely counts. These may portend what lies ahead in battleground states, say legal scholars.

With so many transactions among so many people and in such a charged political atmosphere, “some irregularities are bound to develop,” says Michael Morley, an assistant professor of law at Florida State University in Tallahassee.

In California, where ballots are being mailed to all voters ahead of the election, over 2,000 registered Los Angeles County voters recently received mail-in ballots that didn’t have a section to vote for a president. Officials apologized and said new ballots would be sent.

Minor errors or rampant fraud?

Minor bureaucratic mistakes, say election law experts, don’t add up to the rampant fraud alleged by President Trump and his allies.

Spotlighting minor errors “is different from taking small-bore problems and saying it’s chaos and can’t be successful,” says Richard Hasen, a professor of law and political science at the University of California, Irvine.

Disputes over postal ballots involve questions such as: Do you need a witness? How are signatures verified? Does the ballot need to arrive on Election Day and what if the post is late? Can a deadline be extended once early voting has begun?

Courts have already weighed in on some of these disputes after an initial flurry of lawsuits during the primaries. The Supreme Court ruled on one case in South Carolina on Oct. 5, siding with Republicans over signature validation rules. Another pending case involves Pennsylvania, where the Republican-controlled legislature wants to overturn a three-day extension for ballots mailed by Election Day that Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court upheld. The court is also reviewing a similar extension in Wisconsin, another battleground state.

These cases could set important precedents, even if the vote in those states isn’t close, says Professor Hasen. “If it [the Supreme Court] rules the state legislatures have more powers than courts to set the rules, then that has important implications.”

Not all the disputes involve mail-in voting. Battles are being waged over the rules for in-person voting in precincts that often have long lines because of what Democrats say are deliberate suppression efforts.

Still, most of the scenarios for postelection legal showdowns relate to disputes over the validation of postal ballots. Polls suggest as many as one-third of all voters will mail their ballots. Studies show that a higher proportion of them are likely to be disqualified.

The success of postal voting in states like Oregon and Colorado, which both Republicans and Democrats have hailed for their efficiency, may be an imperfect guide to what could happen elsewhere, warns Professor Morley. “It might look smooth today, but that’s only because it took numerous election cycles to get to that point.”

“Mistakes will happen,” says Franita Tolson, a law professor at the University of Southern California, in Los Angeles. “That’s the importance of giving time to count the vote and to get an accurate count.”

Wide victory margin averts disputes

In the Florida race in 2000, the Supreme Court had to adjudicate between state officials who wanted to certify the initial results and the state’s highest court, which ordered a halt to the recount of disputed ballots. The Supreme Court ruled that the recount process was flawed and no recount could be held in time for the deadline for deciding Electoral College seats.

President Trump said in the Sept. 29 presidential debate that the Supreme Court could decide this year’s election: “I’m counting on them to look at the ballots, definitely.”

That is not a position Chief Justice John Roberts would relish, given the rancor over Bush v. Gore, says Professor Tolson. “He’s very concerned with the legitimacy of the court, and I do think on some level he has internalized the lessons of the 2000 election,” she says.

Mr. Richard, who litigated for Mr. Bush in Florida in 2000, concurs: “I think the Court will not take a case to decide this election unless they absolutely have no choice.”

Some of the top lawyers in Mr. Biden’s camp cut their teeth on the Florida recount battle, including Marc Elias, who is overseeing efforts to protect voter access and ballot counts. Republicans have also hired lawyers from large firms and recruited scores of volunteers and poll watchers to scour for irregularities in swing states.

With just weeks to go, and millions of votes already cast, some legal scholars are looking at polls and wondering if worst-case scenarios – contested ballot counts, postelection unrest – may be averted by an indisputable defeat for Mr. Trump.

“We may squeak by this time,” says Professor Hasan, referring to a clear-cut result. But that’s cold comfort if the same flaws occur next time, in the absence of greater professional and nonpartisan administration of how Americans vote. “Our election system is quite weak.”

Ultimatum signals modest US goal in Iraq: Avoid defeat

In Iraq, the Trump administration is wrestling with two competing goals: its stated desire to halt America’s “endless wars,” and the need to be seen to be withdrawing on its own terms.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s threat last month to shutter the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad if Iraq didn’t rein in militia attacks on American targets was a stunning admission of weakness, analysts say. And it revealed the scale of the dilemma faced by the Trump administration, as it seeks to draw down American forces in Iraq without appearing to be running away from Iran-backed groups.

Further evidence of its dilemma: Despite the attacks, the Pentagon announced last month it was cutting U.S. troop levels by nearly half to 3,000, due to “confidence” in Iraqi forces’ “increased ability to operate independently.”

Washington’s conundrum shows it is a far cry from “deterring” Iran, which U.S. officials claimed to have done by assassinating Iran’s powerful general, Qassem Soleimani, and Iraqi militia leader Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis in a pre-dawn Baghdad drone strike last January.

Indeed, the militia attacks continued up until Secretary Pompeo’s threat, often in the name of revenge for the dead commanders.

“The idea [that the assassinations] would somehow restore strategic deterrence has been blown out of the water,” says Professor Toby Dodge, an Iraq expert at the London School of Economics. “The American footprint is small and getting smaller.”

Ultimatum signals modest US goal in Iraq: Avoid defeat

The threat by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo seemed extreme. The United States would shutter its own embassy in Baghdad if Iraq didn’t rein in Shiite militia attacks on American targets.

The ultimatum late last month – which came with the promise of a “strong and violent” response if the attacks did not stop – was a stunning admission of weakness, analysts say. And it revealed the scale of the dilemma faced by the U.S. in Iraq, as it seeks to draw down American forces without appearing to be running away under fire from Iran-backed groups.

It’s a distillation of how the Trump administration is torn between its stated desire to halt America’s “endless wars,” from Iraq and Syria to Afghanistan, while also withdrawing on its own terms.

The U.S. threat to close up shop also risks making the fragile Baghdad government – buffeted already by the COVID-19 pandemic, shrunken oil revenues, political infighting, chronic corruption, and a year of public protest – even more vulnerable to influence from outside powers.

Mr. Pompeo’s ultimatum may have been issued only to encourage Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi to take a firmer stand against Iranian influence, and do more to rein in the powerful militias. But it highlighted the challenge the White House is navigating between the oft-competing policies of imposing maximum pressure on Iran, which sees in Iraq an opportunity to strike back at the U.S., while simultaneously in Iraq trying to deter Iran.

Further evidence of its withdrawal dilemma: Despite the attacks, the Pentagon announced last month that it was cutting U.S. troop levels by nearly half to 3,000, due to “confidence” in Iraqi forces’ “increased ability to operate independently.”

The rocket and other attacks by Iran-backed militias have now eased, but few believe that U.S. deterrence has been established, or that an offer this week of a temporary truce by some key Shiite militias – including Kataib Hezbollah, which said a “conditional” cease-fire would depend on the U.S. providing a timetable for its “retreat” – is anything more than waiting out the American election cycle.

“The U.S. is trying to avoid defeat,” says Abbas Kadhim, head of the Iraq Initiative at the Atlantic Council think tank in Washington.

“They don’t want to show that they were defeated in Iraq, and were expelled, specifically because Iran has made it clear that their sense of victory would be accomplished by forcing all American forces out of Iraq,” says Mr. Kadhim.

US-Iraq tensions

The vast U.S. Embassy complex – the largest in the world, built to house 3,000 diplomats, but now operating with a skeleton crew due to both security risks and pandemic dangers – is reportedly already in the process of being shuttered.

The threat to close it was a gift to factions in Iraq and Iran that want the U.S. to depart.

“If Iran and its friends’ highest priority is to drive U.S. forces out of Iraq, and you tell them that if they continue to do these attacks, we will take the troops out and shut the embassy, what do you expect them to do, less or more of that?” says Mr. Kadhim. “It seems like an invitation to step these [attacks] up.”

The growth of dozens of mostly Shiite militias – and the overt Iranian backing of several of the most powerful, which operate beyond government command structures – has been an increasing source of tension between Baghdad and Washington.

Stopping those Iraqi militia attacks was a top priority of President Donald Trump when he held a “strategic dialogue” with Prime Minister Kadhimi, a former head of Iraqi intelligence, at the White House in August. The U.S. drawdown was discussed, and the Iraqi leader said afterwards that an American presence was still required in Iraq to help fight remaining Islamic State sleeper cells.

Known as the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), or Hashd al-Shaabi, the Shiite militias were formed in 2014 to help defend the nation as ISIS swept south from Syria, gobbling up a third of the landmass as the U.S.-trained Iraqi army disintegrated.

Since the 2017 defeat of ISIS, however, the PMF have broadened their influence in political circles, deepened their control of economic networks, and angered citizens for leading a crackdown on Iraqi protests that swept the country beginning last October. The heavy-handed measures included the use of snipers and disappearances, which left an estimated 700 dead, as well as the murder of opponents.

Those backed by Iran have increasingly targeted U.S. facilities and troops, forcing American commanders to consolidate their positions in response, at the expense of the anti-ISIS battle.

Far from deterrence

But Washington’s conundrum shows it is a far cry from “deterring” Iran, which U.S. officials claimed had been achieved by assassinating Iran’s powerful general, Qassem Soleimani, and Iraqi militia leader Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis in a pre-dawn Baghdad drone strike last January.

Indeed, the militia attacks on American targets continued, often in the name of revenge for the two dead commanders.

“It looks like the assassination of Soleimani and Muhandis was the last roll of the dice of a Trump policy, and an act of ultimate stupidity and folly,” says Toby Dodge, an Iraq expert at the London School of Economics.

“The idea it would somehow restore strategic deterrence has been blown out of the water. The idea it would shift the balance has been blown out of the water. The American footprint is small and getting smaller,” says Professor Dodge.

The warning to close the embassy signaled two things, he adds. First, it laid out a two-step process that culminated in a threat to use military force – and therefore a recalculation.

“The Iranians and their allies sat up and took notice and thought: ‘We’ve got until November, and then the transition. This man [President Trump] is unpredictable.... So, let’s put things on the back burner, we’ve got what we want,’” says Professor Dodge.

But second, he adds, the pressure on an ostensible ally in the prime minister “shows you how poor U.S. elite analysis of Iraq is,” because it is counterproductive to demand an unambiguous pro-American stance in a country where every politician has “felt the hot breath of Iran down their neck ever since ‘maximum pressure.’”

“The Iranians have been rather astute, and have waited the Americans out,” says Professor Dodge. “You could argue that the Americans have achieved some kind of deterrence by taking their football and going home, but that [shrinking American presence] somehow yields the territory you want to operate deterrence over to your enemies.”

Call for “strategic patience”

The threat to close the Baghdad embassy provoked a firestorm. Former U.S. Ambassador Ryan Crocker, who served in posts from Beirut to Baghdad to Kabul, called for “strategic patience” in Iraq, and told an Al-Monitor podcast that closing the embassy would be “incredibly irresponsible.”

“What we need to stop doing is blaming al-Kadhimi for a situation that he didn’t create but that we did,” said Ambassador Crocker. “It almost sounds as though we are looking for an excuse, now that we’ve pulled out most of our troops, to pull out our embassy as well.”

Others suggested closing the complex, which is “only slightly smaller than Disneyland” and features 20 office buildings, six apartment blocks, and cost $750 million, and instead buying something smaller and “commensurate with its actual mission, role, and influence in Iraq,” notes Steven Cook, a Middle East analyst at the Council on Foreign Relations.

“If the existing complex speaks to the arrogance of the past two decades, a new home for the embassy would symbolize American humility after a misbegotten invasion and occupation,” Mr. Cook writes in Foreign Policy magazine this week.

Yet military withdrawal would be “ultimately counterproductive,” he argues. “Leaving Iraqis to the dangers of the Islamic State and the will of the Iranians would only perpetuate Iraq’s weakness and instability, handing Tehran a strategic victory.”

A letter from

Drive-thru Texas state fair: Fried Oreos, yes. Baby animals, no.

The state fair – in whatever state – is an American tradition. And our Texas correspondent reports that despite a long line, a $65 entry ticket, and his first-timer's skepticism, the new socially distanced drive-thru event is still a communal experience.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

It’s late September, which for 134 years has meant one thing in Texas: the start of the state fair.

I’ve wanted to visit the State Fair of Texas since I moved here in 2017, since I’d read about the funnel cake bacon queso burger and the time Big Tex burst into flames.

This year is the Plague Year, though. Recreation has been banned, frivolity outlawed, until the curve is as flat as a half-empty Topo Chico left in the sun.

But one does not simply move to Texas and reach straight for the funnel cake bacon queso burger. One spends years building gastrointestinal resiliency, as I have. Now it’s 2020, so this year’s offerings are more limited, and available only via drive-thru.

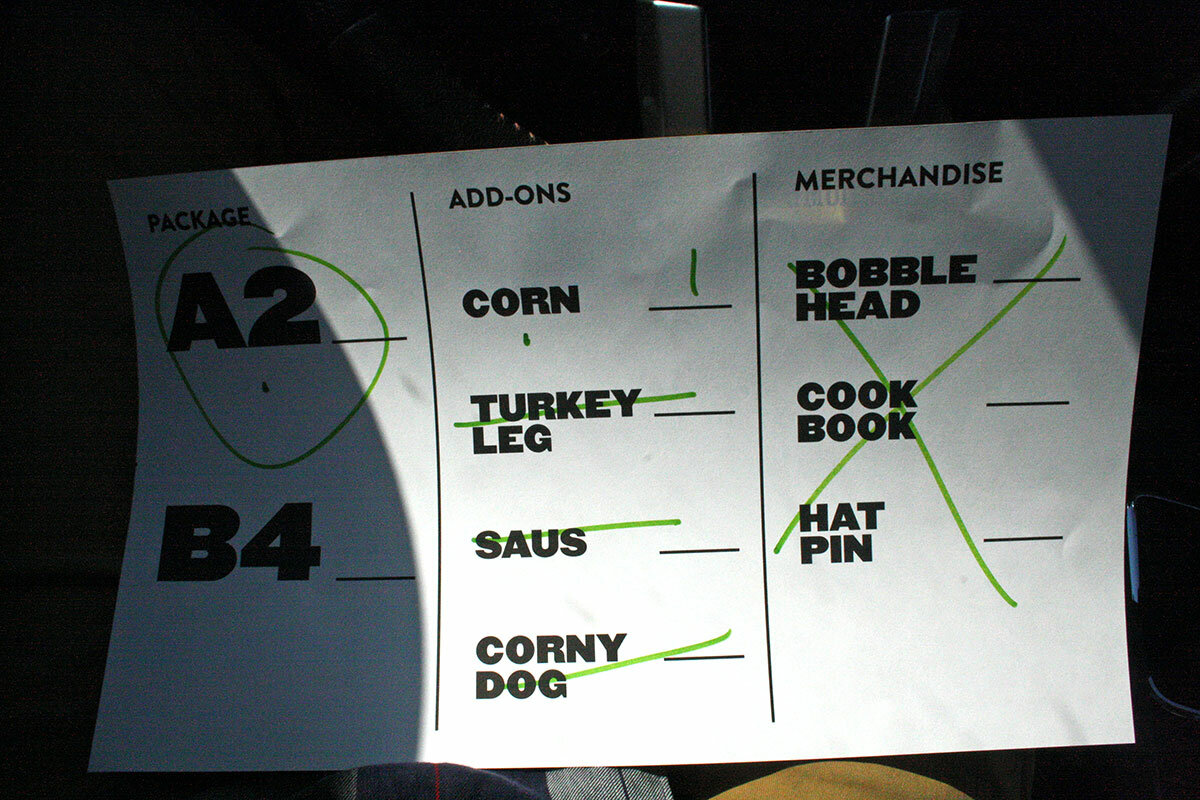

My $65 ticket guarantees me a corn dog, fries, cotton candy and deep-fried Oreos – but no guarantee of when. We arrive at noon and spend the next four hours in the car inching toward food and Big Tex, the 55-foot-tall animatronic cowboy we're all here for. Strange. It feels like we only just entered Gate 11, just like it feels like it was March only last week.

I grew up in England, and deep-frying everything was, I’d thought, an exclusively Scottish pastime. The highlight of my first State Fair of Texas experience? Deep-fried Oreos. Must inform Scotland.

Drive-thru Texas state fair: Fried Oreos, yes. Baby animals, no.

It’s a warm, sunny day, and the drive north up Interstate 35 is as smooth as you can expect that drive to be. It’s going to be a good day, reader.

It’s late September, which for 134 years has meant one thing in Texas: the start of the state fair.

This year is the Plague Year, though. Recreation has been banned, frivolity outlawed, until the curve is as flat as a half-empty Topo Chico left in the sun.

Still, this is my first state fair. I grew up in England, and deep-frying everything was, I’d thought, an exclusively Scottish pastime.

I’ve wanted to visit the State Fair of Texas since I moved here in 2017, since I’d read about the funnel cake bacon queso burger and the time Big Tex burst into flames.

But one does not simply move to Texas and reach straight for the funnel cake bacon queso burger. One spends years building gastrointestinal resiliency, as I have. Now it’s 2020, so this year’s offerings are more limited, and available only via drive-thru. My ticket guarantees me a corn dog, fries, cotton candy and deep-fried Oreos.

Traffic is beginning to swell as I peel off I-35. A Ferris wheel towers above the trees, “TEXAS” emblazoned on its spokes. Enter Fair Park through Gate 11, the ticket instructs. We obey, but the line to enter begins at Gate 5. My girlfriend – here for corn on the cob, not to be quoted in this report – let out a snort of frustration. It is just past noon.

Reader, our frustrations are only just beginning.

We’re in the parking lot now. It’s 1:30 p.m. Another snort of frustration. My girlfriend slips out of her shoes and opens a book.

The cars snake across the concrete in a long, curving U. We’re following a silver Chevy Tahoe. Peering into the other cars – there is nothing else to look at – I see smiles and laughs. I feel the same. The line is long, but it’s moving.

It is a warm sunny day. The Texas summer heat has broken, finally. Or is that just the air conditioning? No, I taste the cool air as I lean out the window to photograph the chain of taillights in front of us.

People are getting out of their cars, even though signs say you shouldn’t. They’re going to the portable toilets. Or walking aimlessly. One man is pushing a stroller.

I take more pictures of lined-up cars, through the car windows this time. Something more artsy.

I should mark the time we entered the gate, just in case!

The line splits into two lanes. Now we’re behind a black Ford F-150 Texas Edition. It’s a bit dustier than the Tahoe. Or is it a clean car viewed through a dusty windshield? As I’m about to say something to my girlfriend about perspective, a car breaks out of line abruptly and heads for the exit.

Strange. It feels like we only just entered Gate 11, just like it feels like it was only March last week! We should play a game, I say. She suggests alphabets, and we hunt surrounding license plates for A’s, B’s, C’s, D’s, etc.

There are no I’s in Texas license plates, apparently. Is there some kind of ban? Do they look too much like a “1”? The game ends.

Oh look, Big Tex! Or a mascot, at least. Children spill out of cars to take pictures with him. That’s nice. I wonder why I can’t yet see the real Big Tex, given he’s a 55-foot-tall animatronic cowboy.

Can you get sunburn through car windows? The back of my shirt is very sweaty. “Wash me” is written in the dust of the F-150 Texas Edition’s tailgate, I notice. My girlfriend has gone for a walk. She’ll be back soon!

More cars left. My surroundings have transformed. They must be photographed, I know. But I’m not sure why.

Right, the reporting trip. Reporting trips have been rare this year. That dining room table was starting to feel claustrophobic! Ah look, my girlfriend is back. And look, we’re at the fair entrance! And it’s not even 5 o’clock!

Fries: Good. Remind me how hungry I am.

Corn dog: Tasty, but dense: B–.

Corn on the cob: Good, my girlfriend says. She eats only one.

Deep-fried Oreos: The highlight. Must inform Scotland.

“With it being a new event it comes with its challenges,” Karissa Condoianis, spokesperson for the State Fair of Texas, tells me a few weeks later. “We’ve fixed it now.”

The lines are shorter now, she says. But while they don’t know how many people are in each car, overall attendance is down too, from more than 2.5 million last year to about 30,000 cars for the four-weekend event that ends Oct. 18.

It’s part of an attempt to replace the fair in aggregate. There’s been a shortened market week and some virtual events as well. The organizers know it’s not a perfect substitute, says Ms. Condoianis, but “it was more about keeping the state fair spirit alive.

On Film

‘Chicago 7’: Fast-talking court drama is a window on protest and America

Movies can enhance our understanding of America. With the arrival of Aaron Sorkin’s “The Trial of the Chicago 7,” film critic Peter Rainer examines the intersection of popular culture and events that define a nation.

-

By Peter Rainer Special correspondent

‘Chicago 7’: Fast-talking court drama is a window on protest and America

Aaron Sorkin’s “The Trial of the Chicago 7” debuts at a time when the political temperature in the United States is practically at full boil. It’s based on the notorious 1969 trial in which seven (originally eight) defendants were charged by President Richard Nixon’s Justice Department with conspiracy to incite violence in the wake of the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Although Sorkin originally wrote the script in 2007, it’s inevitable that the movie is now being promoted, rightly or wrongly, as a mirror image rendering of the civil unrest happening across the U.S.

As a writer-director, Sorkin, by his own admission, is most in his element when his characters are jabbering and pontificating in a confined space, à la his TV hit “The West Wing.” His new film often cuts away from the trial proceedings – including period documentary footage and flashbacks to the street clashes between protesters and the police and National Guard – but the meat of the action, and its best scenes, take place inside Chicago’s U.S. District Court.

Sorkin transforms the prolonged political theater into a showcase for a motley crew of provocateurs, among them, defendants Jerry Rubin (Jeremy Strong), co-founder of the radical Youth International Party (Yippies) and a prankster who looks like he might have stepped out of a Cheech & Chong movie; Abbie Hoffman (Sacha Baron Cohen), another Yippie instigator, whose courtroom antics, by design, are catnip for the media; and Tom Hayden (Eddie Redmayne), co-founder of the somewhat more temperate Students for a Democratic Society, who, amid this company, stands out as the voice of reason.

Their co-chief counsel William Kunstler is played by Mark Rylance in a distracting longhaired wig that makes him look, no doubt intentionally, like a superannuated hippie. Yahya Abdul-Mateen II plays Black Panther Party co-founder Bobby Seale, whose angry outbursts in the courtroom prompt the defendants’ nemesis Judge Julius Hoffman (Frank Langella, sounding like a testier version of his Nixon from “Frost/Nixon”) to bind and gag and eventually sever him from the case.

Sorkin draws on and often embellishes the actual trial proceedings. Some of the film’s best lines were, in a sense, already written for him. When, for example, Judge Hoffman asks Abbie (no relation) if he is familiar with the concept of contempt of court, his gleeful comeback is, “It’s practically a religion for me, sir.” Sorkin overplays the grave jollity inside the courthouse, but as beautifully played by Baron Cohen in easily the film’s best performance, Abbie is the one character whose showboating clearly fronts a deeper concern. When at one point he is asked what his price would be to call off the “revolution,” he answers simply, “My life.”

Clearly Sorkin sees the Chicago 7 as victims of the vilification of dissent. He also sees them as exemplars – this is his version of a superhero movie – and the idealization at times gets a bit sticky. (Hayden, in particular, practically comes equipped with his own halo.) For Sorkin, protest is the highest American virtue. He closes out the film with the Chicago protesters’ rallying cry: “The whole world is watching.”

We can choose to look to this film for confirmation that, even before the pandemic, things have not really changed for the better – that civil rights abuses, racial injustice, demagoguery in high places, and so much else are still rampant. But there are large differences from that time, too – the Vietnam War, for one, without which it’s inconceivable the counterculture would have arisen as it did.

It’s tempting to try to learn about America by looking at its movies. It’s also a trap. This country is too complex for that. Too much, especially in the racial realm, has been left out. As Sorkin has acknowledged in interviews, what comes closer to the truth is that American films – think of the best of John Ford or Frank Capra – can express a longing for a time that never really existed except in our fantasies. This is a different kind of American history. It’s a history of what we want to believe. For all its documentary-like aspects, “The Trial of the Chicago 7” also falls into this category. It represents the sanctification of a time and a people whose spirit Sorkin sees as our salvation.

Peter Rainer is the Monitor’s film critic. “The Trial of the Chicago 7” debuts on Netflix on Oct. 16, and is in select theaters.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A ‘Club Med’ of peaceful petro-states?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

On Wednesday, officials from Israel and Lebanon – two neighbors still technically at war – met inside a tent for their first talks on a nonsecurity issue in three decades. The tent, which belongs to United Nations peacekeepers in southern Lebanon, was an apt metaphor. It symbolizes a widening tent for countries in the eastern Mediterranean to collaborate in tapping newly discovered oil and natural gas in their offshore seabed.

The talks between Lebanon and Israel were limited to resolving a maritime border dispute that is holding up petroleum exploration. Yet their main goal, said Israeli Energy Minister Yuval Steinitz, is to create security and stability for the benefit of all the people in the region.

In different parts of the world, peace has often become a reality when longtime foes find a common interest such as sharing resources. Peace talks between the Palestinians and Israelis, for example, began in the early 1990s over a joint desire to resolve issues over water resources.

What binds neighbors is often greater than what divides them. And supporting each other in tapping natural wealth is preferable to risking conflict.

A ‘Club Med’ of peaceful petro-states?

On Wednesday, officials from Israel and Lebanon – two neighbors still technically at war – met inside a tent for their first talks on a nonsecurity issue in three decades. The tent, which belongs to United Nations peacekeepers in southern Lebanon, was an apt metaphor. It symbolizes a widening tent for countries in the eastern Mediterranean to collaborate in tapping newly discovered oil and natural gas in their offshore seabed.

The talks between Lebanon and Israel were limited to resolving a maritime border dispute that is holding up petroleum exploration. Yet their main goal, said Israeli Energy Minister Yuval Steinitz, is to create security and stability for the benefit of all the people in the region.

In different parts of the world, peace has often become a reality when longtime foes find a common interest such as sharing resources. Peace talks between the Palestinians and Israel, for example, began in the early 1990s over a joint desire to resolve issues over water resources.

Israel and Lebanon are eager to tap the oil and gas off their shores mainly out of domestic pressures for prosperity. Over the past decade, other nearby countries have joined in this quest. In September, Cyprus, Greece, Egypt, Israel, Italy, Jordan, and the Palestinian Authority formed the East Mediterranean Gas Forum, an entity designed to allow friendly coordination in exploration and production.

The outlier has been Turkey. Under the legal norms of the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, its options for offshore drilling are limited. In a belligerent move, it has sent exploration ships into waters claimed by Greece and Cyprus – often accompanied by warships. Greek and Turkish ships actually collided in August. Both the European Union and NATO are trying to calm the tensions caused by Turkey’s actions and extraterritorial claims.

This makes the Israel-Lebanon talks even more important. Formal peace talks between the two countries are not expected. Yet the talks do help widen the tent for regional cooperation.

What binds neighbors is often greater than what divides them. And supporting each other in tapping natural wealth is preferable to risking conflict.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Freed from cynicism, alcohol use, and chronic illness

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By David Olson

Resentful of society, frequently sick, and living a wild lifestyle, a grad student began to yearn for a healthier, less cynical path. Then he came across a magazine about Christian Science healing, and what he learned as he began studying this Science more deeply turned his life around completely.

Freed from cynicism, alcohol use, and chronic illness

During the 1960s period of the Vietnam War, I was a graduate student living with a group of other grad students and involved in political protests, wild parties, and frequent use of alcohol. We thought we were sophisticated, but with hindsight I realized that we were actually hateful and cynical. Often, I would return from political protest marches filled with resentment toward society.

This riled-up state of thought was often accompanied by illness. In fact, I would frequently find myself at the campus health care center with symptoms of flu, mononucleosis, and pneumonia.

My parents were Christian Scientists and took me to the Christian Science Sunday School when I was young, but in college I stopped attending church or studying this Science. Eventually I got tired of being so frequently sick, though. I thought, Why not get back to the healthful lifestyle I had when living with my parents?

One day, I was doing my laundry at a local laundromat and saw a rack containing copies of a magazine called the Christian Science Sentinel. I picked up an issue and read it. The way I felt as I read the articles reminded me of the comforting, spiritual atmosphere I used to feel when attending church.

The following week I met the man, a Christian Scientist, who had left the magazines at the laundromat. He was a very sweet recent immigrant employed as a barber. His manner was such a contrast with the hateful, cynical, pseudo-sophisticated atmosphere that I felt pervaded my apartment.

The barber directed me to the local Church of Christ, Scientist, and I started to attend services there and read the weekly Bible Lessons (found in another publication, the “Christian Science Quarterly”) once again. This led me back to a harmonious and stable lifestyle. I’m so grateful for that happy barber who brought me back to Christian Science and a happy, healthy life.

Soon after returning to studying Christian Science, I realized I was completely free of dependence on the use of medicine and alcohol. I never again missed a day of grad school, and for the next 34 years until retirement, I never had to take a sick day from work. I learned that as God’s children, all of us are governed and maintained by God, divine Mind. As we come to understand this spiritual reality, healing and peace are natural results.

I learned, too, that it didn’t help to resent society for its misdeeds, but it does help to see everyone as the sons and daughters of God, reflecting God’s qualities. Christ Jesus was the best example of how this results in healing. Mary Baker Eddy wrote in the textbook of Christian Science, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures”: “Jesus beheld in Science the perfect man, who appeared to him where sinning mortal man appears to mortals. In this perfect man the Saviour saw God’s own likeness, and this correct view of man healed the sick” (pp. 476-477).

We can all strive to see ourselves and others through this spiritual lens, and experience more of the help and healing this brings.

Adapted from a testimony published in the Oct. 12, 2020, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Hats on for an election

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. We’re glad you’re here. Tomorrow’s Daily will examine how U.S. voters, whose ballots will determine the direction of American democracy, are dealing with high stakes and high anxiety.