- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Split-screen democracy at its frustrating finest

Here’s a pro tip for young aspiring reporters: When interviewing a politician, your most useful responses often come in the follow-up questions and real-time fact-checking.

That was the upshot from dueling town halls last night with President Donald Trump and his Democratic opponent, former Vice President Joe Biden. NBC’s Savannah Guthrie, in particular, stood out for her brisk questioning of President Trump, including on his practice of retweeting conspiracy theories to his 87 million followers.

He said he was just putting the information “out there,” as a way to bypass the “fake” media. Otherwise, he said, “I wouldn’t be able to get the word out.” Ms. Guthrie responded, speaking of an untrue story he had amplified: “The word is false.”

Mr. Biden’s town hall was more staid, but ABC’s George Stephanopoulos pressed hard on whether, as president, he would expand the size of the Supreme Court – a fraught topic. Mr. Biden said he would announce his position before Election Day if Judge Amy Coney Barrett is confirmed to the high court by then, which appears likely. That was news.

Last night was supposed to be a joint town hall debate between Mr. Trump and Mr. Biden, but the debate commission canceled it after Mr. Trump was diagnosed with COVID-19 and he rejected making it a virtual event. The result, dueling town halls on competing networks, made for frustrating split-screen viewing. But such is the state of American democracy – messy but at times enlightening.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Global report

It’s the world according to Trump: Could Biden turn back the clock?

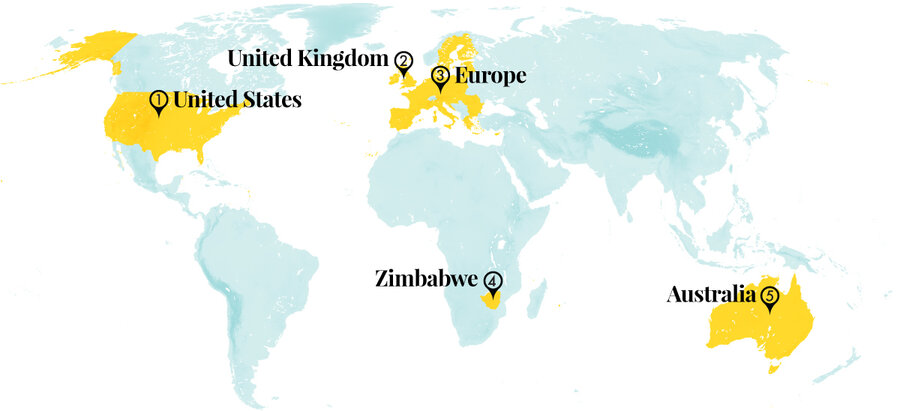

Transactional diplomacy. America First. Autocrats have adjusted to the terms of President Trump’s foreign policy. Our writers explore what might happen if a President Biden tries to revive U.S.-led multilateralism.

In his nearly four years in the White House, President Donald Trump has shrunk from intervening to preserve the U.S.-led global order. As America has pulled back from its leadership role, nations not only have taken notice, but have acted. While the cat’s been away, in a sense, the mice have come out to play.

The exercise of this newfound freedom has been strongest among leaders who find inspiration in Mr. Trump’s “America First” unilateralism. From Brazil to India and Saudi Arabia to Hungary, the leaders have pursued national interests and regional ambitions that an earlier imperial America might have sought to check.

Yet a U.S. election is approaching that may turn the White House over to former Vice President Joe Biden, and foreign policy experts anticipate that a President Biden would seek to refurbish American leadership and reinvigorate multilateralism.

Many say, however, that the nationalist genie may be out of the bottle. “The world is not the same,” says analyst Robert Kaplan. A Biden foreign policy “would seek to challenge” rising authoritarianism and blunt nationalism with multilateralism, he says. But a new administration would soon learn that “on the whole, each country is going on its own.”

It’s the world according to Trump: Could Biden turn back the clock?

When former Vice President Joe Biden used the first presidential debate to tout his plan for a $20 billion international fund to encourage Brazil to preserve its endangered rainforests, it was a shoutout to a bygone era of robust, American-led multilateralism.

But when Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro lost no time in condemning Mr. Biden’s idea as an arrogant stab at national sovereignty, it was a different kind of shout – a reminder that much of the world has already adjusted to the approach of President Donald Trump.

In his nearly four years in the White House, Mr. Trump has shrunk from intervening to preserve the U.S.-led global order. Instead of wielding the influence of a superpower to tackle the issues of the day – from climate change and public health to trade and nuclear nonproliferation – Mr. Trump has preferred a more transactional foreign policy that meets America’s narrower economic and security interests first.

As America has pulled back from its leadership role, nations not only have taken notice, but have acted. While the cat’s been away, in a sense, the mice have come out to play.

The exercise of this newfound freedom has been strongest within what Shivshankar Menon of Brookings India calls the “League of Nationalists” – leaders like Mr. Bolsonaro, India’s Narendra Modi, and Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who find inspiration in Mr. Trump’s “America First” unilateralism.

In the U.S. pullback, they have also found a green light to pursue national interests and regional ambitions that an earlier imperial America would have sought to check.

Yet as the U.S. approaches an election that may turn the White House over to Mr. Biden, much of the world wonders if the cat is away for good – or poised to pounce back.

No one expects anything markedly different from a second-term Trump foreign policy. Yet based on Mr. Biden’s campaign pronouncements and long experience, many foreign policy experts anticipate he would seek to refurbish American leadership and reinvigorate multilateralism.

“World is not the same”

Yet even if a President Biden were to attempt to rein in the new nationalists, many believe that genie may be out of the bottle.

“We are not the same country that we were four years ago, and the world is not the same,” says Robert Kaplan, an influential U.S. analyst of geopolitics and U.S. foreign policy.

A Biden foreign policy “would seek to challenge” a rising authoritarianism and to blunt nationalism with multilateralism, Mr. Kaplan says. But a new administration would soon learn, he adds, that “while the U.S. can nudge the needle 10% in one direction or 10% in another, on the whole each country is going on its own.”

Around the world, leaders have adjusted to Mr. Trump.

In Brazil, for example, many see Mr. Bolsonaro inspired and empowered by the U.S. president as he has fired an independent federal police chief and severely cut the budgets of government agencies meant to protect the environment and indigenous people.

“Trump offers Bolsonaro clear cover,” says Andre Pagliarini, a lecturer at Dartmouth College writing a book on Brazilian nationalism. “He can say … ‘The leader of the most democratic country in the world is a friend and aligned with me, so by definition, I’m not radical,’” Mr. Pagliarini says.

The same holds for other leaders in the Americas.

In Guatemala, former President Jimmy Morales made multiple attempts to disband the regionally admired International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala, finally engineering the commission’s demise before leaving office last January. That action gutted years of U.S. investment in fighting corruption in the region, experts say.

Since Mr. Trump came into office, says Ursula Roldán, a researcher at Rafael Landívar University in Guatemala City, “there’s been a weakening of U.S. interest here that’s in turn weakened our fight against corruption.”

Green lights to autocrats

Other regions are likely to present even tougher challenges to any president seeking to reverse Mr. Trump’s retreat from leadership.

Explicit green lights from the White House have emboldened autocrats in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, and Turkey to suppress freedoms at home, hunt down dissidents abroad, and ramp up proxy wars across the Middle East and North Africa to secure economic and political interests.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE have escalated a war in Yemen and applied pressure in Sudan and Libya, while Turkey and Egypt are extending their influence into Libya.

“America has declared with its actions, inaction, and troop drawdowns that it no longer considers the Middle East critical to its strategic interests,” says an adviser close to Gulf Arab decision-makers, who requested anonymity for security reasons. “We have learned that we … must secure our own national interest with our own two hands.”

If a President Biden were to seek to set an example of U.S. diplomatic reengagement in the region, it would likely start with Saudi Arabia, says F. Gregory Gause III, a Saudi Arabia specialist who heads the international affairs department at Texas A&M University in College Station. Candidate Biden said this month his administration would end U.S. support for Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen and “make sure America does not check its values at the door to sell arms or buy oil.”

Other regional experts assert that uncertainty over the outcome of the U.S. election is prompting some regional autocrats to accelerate territorial grabs in Libya and Syria.

Ironically, it could be one of the Trump administration’s diplomatic successes that ends up serving as a blueprint for a Biden administration in the region.

When Sudan’s post-dictatorship political transition turned violent in June 2019, with Saudi- and UAE-backed paramilitary groups killing and torturing protesters demanding a civilian government, the U.S. stepped in. The result: an agreement for a mixed civilian-military interim government to oversee a three-year political transition, underscoring how the U.S. retains considerable leverage in the region.

Anti-war sentiment

Yet that does not mean the U.S. is about to reverse its retreat, no matter who occupies the White House. Indeed, the underlying reason for the U.S. pullback from the Middle East is Mr. Trump’s rejection of what he calls “endless wars” – such as those in Afghanistan and Iraq. The president has found broad support for that stance from the American public – a reality not lost on Mr. Biden, who has sounded Trump-like on ending “these forever wars.”

Conventional wisdom has it that Iran especially has benefited from the influence vacuum left by the diminishing U.S. military footprint. But it is the gains of outside actors in less visible conflicts – such as those in Syria and Libya – that most clearly expose the risks of American disengagement.

When Mr. Trump ordered 1,000 American troops out of northern Syria in October 2019, abandoning Kurdish militias trained by U.S. Special Forces to fight the Islamic State, critics faulted him for forsaking friends and ceding influence to Russia, Iran, Turkey, and others. But it was President Barack Obama’s earlier distancing from rebels arrayed against Syrian President Bashar al-Assad that told democratic forces across the region that the days of U.S. interventions for democratic governance were over.

That realization would be sustained in Libya – where U.S. disengagement following the 2011 overthrow of strongman Muammar Qaddafi paved the way for other outside players, including Turkey, to back opposing sides in the conflict between the United Nations-backed government in Tripoli and a rebel regime in eastern Libya.

Yet while Mr. Trump’s desire to end America’s long wars largely explains his disengagement from the Middle East, another reason altogether may be behind his laissez-faire attitude toward the world’s new nationalists.

If Mr. Trump has not sought to rein them in, some experts say, it is because he identifies with them. And this may be true nowhere more than with India, where the president has developed a close relationship with Mr. Modi, the Hindu nationalist prime minister.

“We’ve learned that it’s a very personal prism through which President Trump sees other leaders,” says Navnita Behera, a professor of political science at Delhi University. “And so when we see [Mr. Trump’s] policies on refugees, on illegal immigrants, and his views toward white nationalism, we understand his close friendship with Mr. Modi,” she says. “The two identify with each other.”

Professor Behera notes that President Trump steered clear of the controversy flaring over Mr. Modi’s Muslim-excluding citizenship law when he visited India in February. Nor did the U.S. have much to say about Mr. Modi’s revocation of majority-Muslim Kashmir’s autonomy in 2019.

Professor Behera believes Kashmir is the kind of potentially destabilizing regional issue that a Biden administration would try to influence.

“And that,” she adds, would “force both sides to come up with a better set of rules of engagement than the two leaders’ personal relationship.”

Trump’s “bad boy” admirers

Mr. Trump’s identification with nationalist leaders has also played a part in the close relations the U.S. has developed with two of the European Union’s nationalist “bad boys” in Poland and Hungary.

In both countries, sky-high public approval for Mr. Trump is shared among the top echelons of government, analysts say, where leaders are relieved that the Trump administration seems to care little about democracy or human rights.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has chipped away at the rule of law and the independence of media, while most recently concentrating power through a law allowing him to rule by decree.

“The election of Trump, such an important international actor, emboldened similar discourse in Hungary,” says Dr. Zsuzsanna Végh, a political scientist at European University Viadrina in Frankfurt.

Poland is on a similar path, with Mr. Trump and right-wing populist President Andrzej Duda professing to share many of the same values. “I sometimes joke that we Poles have put on the MAGA T-shirt more than many other countries,” says Michal Baranowski, director of the German Marshall Fund’s Warsaw office.

The Trump administration, which responded to Polish jitters over Russia, its geopolitically ambitious neighbor, by moving U.S. troops from Germany to Poland, has said nothing about erosions of Poland’s independent press and judiciary.

That could change under a President Biden, some European experts believe. They expect a Biden administration would work to reinvigorate the NATO-centered transatlantic alliance – with renewed focus on shared democratic values.

To be sure, there are exceptions to the narrative of America’s global retreat. The Trump administration has intensified America’s focus on China and its periphery, labeling Beijing a strategic competitor that is undermining the international order.

Economically, Washington has imposed tariffs on hundreds of billions’ worth of Chinese goods, while cracking down on intellectual property theft and China’s infiltration of U.S. government-funded research.

Citing threats to national security, Washington has placed restrictions on a widening range of Chinese technology. The U.S. has stepped up patrols in the South China Sea, and increased arms sales to Taiwan.

Across Asia, the expectation is that a President Biden would largely continue the tough stance, while doing more to reassert U.S. leadership in the Indo-Pacific region and return human rights to the core of U.S. foreign policy.

A welcome inattention

While that return to a more traditional U.S. foreign policy might be cheered by some allies, it would not sit so well with others who have welcomed a less attentive America.

Those would likely include the Philippines, where President Rodrigo Duterte has racked up an abysmal human rights record while showing open disdain for foreign leaders who meddle in other countries’ domestic affairs.

A President Biden could learn quickly from Mr. Duterte just how complicated it would be to push back on the newly emboldened nationalists.

Mr. Biden would lose Mr. Duterte “the moment he or any U.S. official” dared to criticize the Philippines over extrajudicial killings, suppression of a free press, or detention of political enemies, says Herman Joseph Kraft, a political science professor at the University of the Philippines.

That could mean losing a strategic ally in the fight for freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, or abrogation of a binational accord allowing joint training of American and Filipino soldiers on Philippine soil.

It could also push Mr. Duterte and others like him deeper into China’s arms – not the outcome a new president looking to burnish American global leadership would want to encourage.

Contributing to this report were special correspondent Whitney Eulich in Mexico City; special correspondent Taylor Luck in Amman, Jordan; staff writer Scott Peterson in London; special correspondent Lenora Chu in Berlin; correspondent Aie Balagtas See in Manila; and staff writer Ann Scott Tyson.

When migrants fall through the cracks in France, volunteers step in

How successful a country is at integrating migrants often depends as much on the public’s willingness to help newcomers as it does on the government’s. In France, the population is lending a hand.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Since the 2015 European migration crisis, when more than 1 million people arrived on the continent and paralyzed governments, France has seen a consistent uptick in the number of asylum-seekers. The increase has put pressure on the government to meet demands for housing and jobs, and effectively integrate new arrivals.

But the government hasn’t been able to keep up with the realities needed to successfully welcome the continuing influx. And so French society has stepped into the gaps.

Nonprofits have been essential in picking up the slack where French bureaucracy has fallen short. In addition to offering legal aid, they provide French classes and help in finding housing. This kind of support is essential, they say, especially because, for all the money the government spends on migrants, state services are so overwhelmed that many migrants are forced to leave.

“The idea is that you should integrate first and then we’ll help you,” says Sarah Belaisch of nonprofit La Cimade. “What we’re trying to show is that doing this is extremely difficult if you’re undocumented.”

When migrants fall through the cracks in France, volunteers step in

It was in 2018, right after two dilapidated buildings had collapsed in her adopted city of Marseille. Elodie Marie was wandering around her neighborhood, contemplating the thousands who had subsequently been displaced, and the lack of housing for poor people, when she spotted a small group of men on the street.

“They had a desperate look on their faces,” says Ms. Marie. “I asked them what they were doing there, and they said, ‘We don’t have anywhere to sleep.’”

The group of African migrants had just arrived from Italy when the building collapses forced them onto the street. Ms. Marie told two of them, 20-somethings from Gambia, they could stay at her place that night. She locked her bedroom door, wondering if she were crazy, and hoped for the best.

One slept on her couch for a month, the other for 10. They helped cook meals; she helped them navigate French bureaucracy as they applied for asylum. Two years later, she still speaks to them regularly.

“I finally saw the reality [of what it meant to be a migrant],” she says. “It was like a slap in the face.”

Since the 2015 surge, when more than 1 million people arrived on the European continent and paralyzed governments, France has seen a consistent uptick in the number of asylum-seekers. In 2015, about 71,000 people applied for asylum and in 2019, over 170,000. The increase has put pressure on the government to meet demands for housing and jobs, and effectively integrate new arrivals.

But despite the values it initially set out to uphold, the government hasn’t been able to keep up with the realities needed to successfully welcome the continuing influx. And so a large swath of French society, including Ms. Marie, has stepped into the gaps. Around 38% of the French population is estimated to be involved in volunteerism of some kind.

“We’re seeing an increase in demands for asylum as well as an increase in difficulties to obtain housing, food, and documentation,” says Héloïse Mary, the president of BAAM, a Paris-based nonprofit that aids migrants. “But we’re also seeing that the commitment of volunteers has not stopped. That’s the positive side in all this.”

France’s migration problem

The 2015 migrant crisis saw the largest wave of people seeking asylum on European soil since the Schengen Agreement in 1985. European Union member states, Switzerland, and Norway registered a record 1.3 million asylum applications that year, with Germany, Hungary, and Sweden receiving the highest numbers.

But while France was one of the leading destinations for asylum-seekers between 2000 and 2010, it fell short of public expectation in 2015, receiving roughly the same amount of applications as in previous years. According to a 2016 poll by the Pew Research Center, 70% of French people disapproved of the EU’s handling of the refugee issue.

The EU member states remain divided over how to reform the asylum system across the bloc. But even as that debate continues, the French government has recognized its own stagnating immigration system, calling it neither satisfactory nor sustainable. Migrant camps have continued to form in and around Paris in recent years, despite repeated evacuations. In 2017, France received more than 100,000 asylum applications, putting pressure on the country’s already strained accommodation system. That same year, French President Emmanuel Macron promised that no one would be left sleeping on the streets by the end of the year.

But many French nonprofits say the government hasn’t been concrete enough in its objectives, and that administrative and housing hurdles have only increased in recent years.

The dismantling of migrant camps, like the massive Jungle in Calais in 2016, has left thousands displaced, and as of 2019, one out of every two asylum-seekers in France were homeless. On Sept. 1, more than 200 families camped out in front of the Paris city hall, in cooperation with nonprofit Utopia56, to call attention to the lack of housing for migrants.

Meanwhile, local prefectures have been so bogged down by demand that many people looking to apply for work or asylum visas can’t even get an appointment, leaving no paper trail for their efforts. For those unable to speak French, the challenges are amplified.

Nonprofits like BAAM and La Cimade have been essential in picking up the slack where French bureaucracy has fallen short. In addition to offering legal aid, they provide French classes and help in finding housing. This kind of support is essential, they say – especially because, for all the money the government spends on migrants, state services are so overwhelmed that many migrants are forced to leave.

“The idea is that you should integrate first and then we’ll help you,” says Sarah Belaisch, director of national agenda at La Cimade. “What we’re trying to show is that doing this is extremely difficult if you’re undocumented.”

“There are people who need help”

Amid a raging COVID-19 pandemic, Europe must still tend to managing migration, whether it concerns economic migrants or asylum-seekers. France and Britain have been at odds in recent months, as the British government has renewed its calls to make the Channel crossing between the two countries nonviable. No one knows exactly how Brexit will affect future migration regulations.

But one upside of the pandemic has been more creative thinking and cooperation between nonprofits, local businesses, and the government. Across France, hotels have opened their rooms – left empty by the drop in tourism – to those without housing. Many nonprofits have continued to carry out their activities, even if much of their volunteer work is face-to-face and comes with a certain amount of risk.

“There would be no French classes for asylum-seekers, no free legal aid,” says Ms. Mary, the president of BAAM, “if nonprofits weren’t doing something about it.”

In order for nonprofits to function fully, of course, it takes interest from the community. Marion Jagu of Paris says she has always felt France should be doing more for migrants, and that’s why she volunteered with BAAM in 2017 to be paired up with someone in need of language and legal help.

Three years later, Ms. Jagu still meets for dinner every Friday with Abdo, a Sudanese asylum-seeker who has since received his French nationality. Even during France’s COVID-19 lockdown, they upheld their end-of-the-week ritual – over Zoom. He’s become like family, meeting her parents and attending her wedding.

“There are people who need help and [in France] we have the means to help them,” says Ms. Jagu. “Everyone deserves to be welcomed with dignity.”

Opportunity strikes: More women behind Bollywood’s cameras

Streaming services have changed the game for film fans: Going to the movies means opening up your laptop on the couch. But they're changing what happens behind the camera too – especially for women.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Bhavya Dore Correspondent

Take a few popular shows in India today: “Mentalhood,” about multitasking mothers; “Baarish,” a love story; and “Four More Shots Please,” often described as an Indian “Sex and the City.” What do they have in common? At least two things: All are produced by streaming platforms, and all are directed by women.

Many female filmmakers say they’ve struggled to break into Bollywood. But here, as elsewhere, streaming services are opening up opportunities. And that means not just more women behind the camera, but more women in front of it – and more complex female characters.

Platforms like Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Hotstar are transforming the scope and variety of stories being told. Liberated from the usual pressures of box office results, exhibition, and distribution, filmmakers are finding new possibilities.

Sooni Taraporevala’s real life-inspired film “Yeh Ballet,” released this year, follows two Mumbai boys pursuing their dancing dreams.

“If it had been financed by conventional producers for theatrical release, I would have got two rupees to make it,” says Ms. Taraporevala. “It’s gratifying for me as a filmmaker to be able to tell stories that are real, without stars, on niche subjects, get the budget the film needs, and have it be promoted well.”

Opportunity strikes: More women behind Bollywood’s cameras

“Guilty,” a Netflix original film, bears little resemblance to commercial Bollywood cinema. Set on an Indian college campus, it tackles the often-taboo topic of sexual assault. The cast boasts no major male stars, nor dance numbers. And unlike most theatrical releases, it was directed by a woman.

The film was released in March, and was frequently on Netflix India’s “Top 10” panel. But director Ruchi Narain, best known for writing a critically acclaimed drama in 2003, often faced a question: “Why has it taken you so long [between films]? Where did you go?”

“I’m like, nowhere!” she says, chuckling. “I was right here. I was flogging my scripts, meeting actors, doing everything any filmmaker does.”

For Ms. Narain, a streaming platform offered opportunities the rest of the film industry had not. In Bollywood, “money rides on male stars, and male stars have their own concerns. They may or may not want to take instructions from a woman, whether they say that or not,” she says.

Film industries in India – of which the Hindi-language Bollywood is the biggest – churn out more than 1,500 films a year. But Bollywood’s closed-in, clubby nature and risk aversion have historically sidelined women-led films, many industry experts say.

But here, as in other countries, that is changing. Platforms such as Netflix, Amazon Prime, Disney+ Hotstar, Voot, Zee5, and ALTBalaji are transforming the scope, scale, and variety of stories being told. A PWC India-Assocham report in 2018 estimated the industry would more than double in value from 2017 to 2022, reaching almost 54 billion rupees (then around $820 million). Liberated from the usual pressures of box office results, exhibition, and distribution, filmmakers in general are finding new opportunities in the digital space.

“The transition from single-screen theaters to multiplexes made a huge difference for women and the kinds of stories” that get told, says Ms. Narain. “Like that, the transition to digital is going to bring a sea change.”

Alankrita Shrivastava is one of the writers and directors behind Amazon’s acclaimed web series “Made in Heaven,” a drama about two wedding planners and their personal and professional lives. It was praised for its canny depiction of urban India, and its deft treatment of themes of sexuality, class, and marriage. She describes roadblocks in the industry as a complex set of interlocking factors. Women may be less interested in the hero-focused films favored by studios, for example; may not find recognizable actors to cast; and then struggle to market their films, affecting earnings. This leads to a cycle, reinforcing the notion that movies made by or led by women are less bankable.

“Definitely streaming platforms are more democratic. There’s more space for diverse voices and women,” says Ms. Shrivastava. “A lot of the network executives are women and open to different kinds of content.”

Streaming shift

There is no reliable national data on the proportion of Indian programming that is women-helmed, but the increase in the number of women behind the camera appears to line up with worldwide trends.

Across U.S. platforms, women jumped from 12% of directors in 2014-15 to 30% in 2019-20, according to the latest “Boxed In” study by Martha M. Lauzen, founder and executive director at the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film at San Diego State University. When just streaming platforms were considered, the figure went from 10% in 2017-18 to 32% in 2019-20. This year, the study notes, streaming services “featured substantially more female protagonists” than cable or broadcast programs: 42%, 27%, and 24%, respectively.

“For film there can be only one director. For episodic [formats] you can have a female director for every episode,” says Madeline Di Nonno, chief executive officer of the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media. “So, with the proliferation of streaming platforms – Netflix, Amazon, Disney+, HBOMax, Peacock, Quibi – you have many more new and global distribution outlets that have to fill their pipeline with content.” However, she also points out that "Boxed In" found 76% of programs studied across platforms had no women directors, and 73% had no women creators.

Some platforms say they are actively committed to rectifying imbalances.

“We have always encouraged women, be it within the organization, in our shows, or behind the camera,” says Ekta Kapoor. As joint managing director of Balaji Telefilms, one of India’s biggest entertainment companies, and managing director of ALTBalaji, its streaming platform, Ms. Kapoor has often been described as one of the most powerful women in television. “As they say, content is reflective of the thought process of the creators; we at ALTBalaji have always strived to break the existing stereotypes.”

Among ALTBalaji’s most popular shows are two directed by women: “Mentalhood,” about multitasking mothers; and “Baarish,” a love story. One of Amazon Prime’s most talked about shows here is “Four More Shots Please” – often described as an Indian “Sex and the City” – and Netflix is this year working with 30 women producers and directors. In 2020, in addition to “Guilty,” the platform released Ms. Shrivastava’s film “Dolly Kitty Aur Woh Chamakte Sitare,” about two women cousins in North India finding themselves, and Sooni Taraporevala’s real life-inspired film about two Mumbai boys pursuing their ballet dancing dreams.

“If it had been financed by conventional producers for theatrical release, I would have got two rupees to make it,” says Ms. Taraporevala, of “Yeh Ballet.” “It’s gratifying for me as a filmmaker to be able to tell stories that are real, without stars, on niche subjects, get the budget the film needs, and have it be promoted well.”

More stories on screen

More women behind the camera also has a ripple effect for women in front of it. “We have found from our previous research that when there is a female writer-director it directly impacts the percentage of female characters on screen,” says Ms. Di Nonno, of the Geena Davis Institute. “Women are 51% of the population, and as such need to see their stories told authentically onscreen.”

Nor are the gains just for women. With digital services, every film or show does not need to cater to every viewer, opening up more opportunities for different stories. Audience diversification and fragmentation “means women get more opportunities because now you are telling all kinds of stories,” says Ruchi Joshi, who co-directed one web show and is in talks for another. “We are making shows for people across classes, across genders.”

As yet, India’s digital shows have been relatively untouched by censorship, allowing greater freedom in portraying women’s lives. Filmmakers and executives believe it has also allowed flawed and more complex women characters to take shape. “With more female creative helms – be it writers, directors, producers – comes more female characters, with more agency, better representation and more engaging plots and themes – something that has never been portrayed before,” says Aparna Purohit, head of India Originals at Amazon Prime Video.

With theaters shut until now, amid the pandemic, even more people have turned online for entertainment. Films meant for theatrical release have opted to go digital, including Ms. Shrivastava’s latest.

But she highlights the charm of watching big screen films, while warning against treating digital platforms as a panacea for gender gaps. “Just because streaming platforms are relatively more democratic shouldn’t be a reason to edge women out of the commercial theatrical space,” she says. “I think there should be equality in all mediums.”

Points of Progress

Dozens of species saved from extinction

From new land rights for women in Botswana to fast-rising renewable energy production in Europe, end your week with stories of progress from around the world.

Dozens of species saved from extinction

World

Conservation efforts have saved up to 48 bird and mammal species from extinction since a 1993 global agreement to protect biodiversity. Scientists at Newcastle University and BirdLife International analyzed a list of 17,046 species to identify which birds and mammals would likely have gone extinct without intervention. They concluded that extinction rates would have been three to four times higher, likely claiming the California condor, Iberian lynx, pygmy hog, and Puerto Rican Amazon parrot. Estimates show between 21 and 32 bird species have been saved through invasive species control, zoo conservation, and habitat protection, and between seven and 16 mammals have avoided extinction through legislation, introduction programs, and zoo collections.

Researchers say the study is a “glimmer of hope” for groups disheartened by the United Nations’ bleak Global Biodiversity Outlook report for the 2011-20 period. “We usually hear bad stories about the biodiversity crisis and there is no doubt that we are facing an unprecedented loss in biodiversity through human activity,” said Phil McGowan, a Newcastle University professor who co-led the study. “The loss of entire species can be stopped if there is sufficient will to do so.” (The Guardian)

1. United Kingdom

The 2020 Booker Prize shortlist is the most diverse it’s ever been, with four of the six finalists being writers of color. The list also includes several debut novelists, including Brandon Taylor and Avni Doshi. Diversity remains a persistent issue in the literary world, with recent surveys suggesting Black, Asian, and other ethnic minority staffers make up only 11% of the U.K.’s publishing industry. Established in 1969, the annual Booker Prize honors the best original English-language novel published in the United Kingdom. Winners receive £50,000 ($63,600).

Bernardine Evaristo, who won the 2019 Booker Prize for her book “Girl, Woman, Other,” tweeted about her excitement regarding the makeup of this year’s shortlist. “It’s all about who’s in the room and the value they place on different kinds of literature,” she wrote. “If you’re looking for fresh perspectives and narratives, surely you’re going to find it among the most underrepresented voices?” The ceremony for this year’s winner will take place on Oct. 27. (Bustle)

2. Colombia

For the first time, former members of the FARC rebel group have apologized for kidnappings and other war crimes committed during Colombia’s decadeslong civil war. A 2016 peace agreement ended the violence, but until now, many ex-guerrillas have been reluctant to acknowledge their specific crimes. Eight top commanders of the now-disbanded group signed an apology, acknowledging the kidnappings were an “extremely grave mistake” and asking victims’ families for forgiveness. Experts say this is an important step forward in a long reconciliation process. Still, many in Colombia say the deal lets former guerrillas off lightly. All eight signatories are now part of the FARC political party, established in exchange for disarmament. A special court also offers ex-FARC members and other war criminals reduced sentences if they confess to their crimes upfront. “This is a big first step in the right direction,” said Kyle Johnson, co-founder of the Bogotá-based Conflict Responses Foundation. “But there’s still a long road ahead. A lot of victims want the truth, not just an apology.” (BBC, Vice)

3. Europe

A report by Europe’s leading national electricity associations and companies says up to 80% of electricity generated in the European Union could be fossil fuel-free by 2030 despite ongoing economic turmoil. In the first half of 2020, two-thirds of the bloc’s electricity was carbon-free, and renewables generation increased to 40% of the overall electricity mix. A decade ago, renewables accounted for 20% of the EU’s electricity.

“This year, the power sector has proven its crucial value for society by providing hospitals, government offices, and millions of home-working Europeans with clean and reliable power,” said Kristian Ruby, secretary-general of Eurelectric, the group that published the report. Remaining barriers to wind and solar capacity could still keep the EU from hitting its 2030 targets, the association warned, and the pandemic will likely delay permit procedures and slow down progress. (Reuters)

4. Botswana

An amendment to the 2015 Land Policy in Botswana expands women’s rights to own land. Before now, land rights were only granted to unmarried women or wives of men who were not already landowners. While the government can issue deeds to anyone with a legitimate claim to land, that process could take decades, leaving millions of women – widows, single mothers, and many wives – vulnerable. The new policy grants equal eligibility to a residential plot anywhere women choose. President Mokgweetsi Masisi called on local authorities and nongovernmental organizations to launch campaigns educating women about their rights under the Revised Botswana Land Policy of 2019. Women’s rights activist Tunah Moalosi said she applauds the move, which will protect widows and “allow women to be independent in marriages.” (Thomson Reuters Foundation, Anadolu Agency)

5. China

A new analysis shows many Chinese cities have reduced fine particle air pollution by an average of 33% in recent years. Researchers studied levels of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) – pollution particles with a diameter less than 2.5 micrometers that linger in the air longer, creating a haze – in all of China’s provinces, municipalities, autonomous regions, and special administrative regions. They found that PM2.5 and its associated risks decreased significantly in 74 key cities from 1990 to 2017. Experts acknowledged that 81% of the population still lives in regions with PM2.5 concentrations exceeding World Health Organization guidelines, stating that “with further economic development in China, more sustainable development policies should be instituted and enforced.” The drop comes after massive efforts to curb emissions throughout the country, especially from households. The proportion of families cooking with solid fuels, such as coal, has decreased from 61% in 2005 to 32% in 2017, as the government promotes clean energy alternatives. (The Lancet)

Essay

A jungle has developed in my digital library

A digital camera is a great tool for an artist who wants to capture a hummingbird’s best side. But 4 billion photos later, this essayist finds herself pining for old-style scrapbooks.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Murr Brewster Correspondent

Way back last century, when cameras first went digital, my husband, Dave, thought I should get one. He said it would be really useful for my artwork. I didn’t want it, because I’d have to learn something new, and sometimes that makes me cranky. He bought it for me anyway, and I had to admit, it was slick.

Now I could take a hundred pictures in a row of my resident hummingbird, in case he turned his head just right and I got the bright magenta iridescent flash. Three or four of the images would be terrific, but all hundred of them would be in my computer.

I’ve now taken 4 billion photographs or so, and they’re all in that machine somewhere. If I need to find a photo, I have to remember about when I took it, and that is not my strong suit.

I do love this technology. But I miss the old photo albums. I remember which photos are in the thin green album, and which are in the thick brown one. And they’re more fun. Your friends will tell you that they want to see the photo of your puppy on your cellphone, but they’re just being polite.

A jungle has developed in my digital library

Way back last century, when cameras first went digital, my husband, Dave, thought I should get one. He said it would be really useful for my artwork. I didn’t want it, because I’d have to learn something new, and sometimes that makes me cranky. He bought it for me anyway. A week later, I wanted to draw a picture of a tyrannosaur peering through ginkgo leaves – as one does – but I didn’t have any reference material for a ginkgo tree. (The tyrannosaur was hard to come by, too.) So I took my new camera a couple of blocks away and fired off some shots of a local ginkgo tree. My computer hoovered them right up and displayed them for me. I had to admit, it was slick.

It took better pictures than my fancy camera, and the images cost nothing to process. Now I could point it outside my window and take a hundred pictures in a row of my resident hummingbird, Hannibal Nectar, just in case he turned his head just right and I got the bright magenta iridescent flash. Three or four of the images would be terrific, but all hundred of them would be in my computer.

I’ve now taken 4 billion photographs or so, and they’re all in that machine somewhere. I never labeled anything, and I still don’t know where the cloud is. So if I need to find a photo, I have to remember about when I took it, and that is not my strong suit.

In fact, if you asked me to name three things that happened to me in the ’80s, I wouldn’t be able to stick a pin into any one thing for certain. One of the things would have really taken place in some other decade, and one of them would have happened to somebody else altogether that I have confused myself with.

There has to be a way of organizing these things. Somewhere I have a good photo of an automobile completely covered in moss. It would be a great illustration for an essay about our local climate. I needed it once, and by the time I’d flipped through all 4 billion photos on my machine I realized I could take a new photo of a different mossy car faster than I could find the original, and I was right. I don’t know where anything is in my photo library, and I have no idea what to do about it. It’s like riffling through my entire vocabulary in alphabetical order to find the end of my sentence.

In fact, I happen to know it’s exactly like that.

I do love this technology. But I miss the old photo albums. I remember which photos are in the thin green album, and which are in the thick brown one. And they’re more fun. Your friends will tell you that they want to see the photo of your puppy on your cellphone, but they’re just being polite.

Everyone is so tired of looking at a screen. People do still like pawing through the old albums. Time passes more reasonably in the albums; flip a couple of pages, and you gain a few years.

They look at pictures of you 30 years younger, and then look back at you like you’re a cautionary tale. They’re alarmed, but entertained. Someday my computer will blow up and take my photos with it, and that will be that. It’s just as well. I still have the old albums. I’ve put on a few pixels since then.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A light shines on Nigerian corruption

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For decades in Nigeria, businesspeople have accepted that corruption is the cost of doing business. In recent days, however, mass protests have dealt a blow to that pessimism. People are less fearful and less resigned to the inevitability of corruption and the system of patronage that comes with it.

“This protest is not just about [corrupt police] but about bad governance,” said a 27-year-old lawyer. According to the latest Transparency International survey, more than half of Nigerians believe most or all public officials are involved in corruption.

In recent years, youth-led protest movements have erupted around the world demanding honest governance. Now it is Nigeria’s turn. Instead of Africa’s most populous country remaining an icon of corruption, its youth have opened a door for it to be a beacon.

A light shines on Nigerian corruption

For decades in Nigeria, businesspeople in Africa’s largest economy have accepted that corruption is the cost of doing business. They have witnessed the failure of successive anti-corruption initiatives by government. The current elected president, Muhammadu Buhari, even headed the African Union’s corruption awareness campaign in 2018. Despite these efforts, the country is still ranked low on a global corruption index. According to a poll last year by Transparency International, nearly half of Nigerians who engaged with a public service – schools, police, utilities – said their transactions involved graft.

In recent days, however, mass protests have dealt a blow to that pessimism. The spark was the killing of a young man by members of a special plainclothes police unit notorious for murder, torture, and extortion. A video of the incident went viral. The outpouring of popular anger prompted Mr. Buhari to announce that the unit, the Special Anti-Robbery Squad, would be abolished.

Given that government leaders had already promised four times to disband the unit, his announcement felt flat. The largely leaderless protests have continued across major cities. As if to confirm the protesters’ skepticism, police keep using heavy-handed tactics against them. The military announced it too was prepared to step in.

Many Nigerians seem unfazed. They are less fearful and less resigned to the inevitability of corruption and the system of patronage that comes with it. “This protest is not just about [the police unit] but about bad governance,” a 27-year-old lawyer told The Wall Street Journal. According to the latest Transparency International survey, more than half of Nigerians believe most or all public officials are involved in corruption.

Mr. Buhari, a retired general who led a military government in the 1980s, can claim some credit for shifting public expectations. Since returning to power five years ago, this time as a democratically elected civilian, he has launched several investigations of high-profile officials and bolstered protections for whistleblowers. His anti-corruption agencies have recovered billions in pilfered public funds. Police opened a call center to field and investigate public complaints of misconduct.

These measures may be achieving only modest or halting results. But they are helping to build awareness that norms of honesty, accountability, and transparency are possible and expected. A 2017 Chatham House survey of Nigerian attitudes toward corruption found that “if people were aware of how commonly held their personal beliefs are, they would be more motivated to act collectively against corruption.”

That survey foresaw the current protests: “Anti-corruption efforts may have the greatest chance of success if they stem from a shared sense of responsibility and urgency – and thus foster collective grassroots pressure.”

In recent years, youth-led protest movements have erupted around the world demanding honest governance. Now it is Nigeria’s turn. Instead of Africa’s most populous country remaining an icon of corruption, its youth have opened a door for it to be a beacon.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Effortless reflection

While the world would have us define ourselves from a material standpoint, a better understanding of God and God’s creation reveals a higher view of ourselves as spiritual, loved, and whole.

-

By Kim Hedge

Effortless reflection

At one point, shortly after I moved into a new apartment, my sister was looking in the long mirror I had hung on my bedroom door. She commented that it seemed like the kind of mirror you would find at a circus in a hall of mirrors – where some make you look very long and thin, others make you look short and round, and so on.

She told me mine was making her look short and round, like she was being squished from the top. The next day she brought me a new mirror. In this one the reflection was perfectly normal, not distorted.

For the previous couple of years, I hadn’t had a great sense of body image. I struggled a bit with my weight, but it wasn’t so much because of the number on the scale as it was due to the fact that every time I looked in that old mirror, I felt I looked short and fat. However, about a week after getting that new mirror, I noticed my perception of myself had changed. Nothing had actually changed physically, but the picture had been corrected. A clearer view of myself – simply looking more like my normal self in that mirror – brought about a change in my thinking.

I found this entire experience to hold larger lessons than just what a mirror was telling me about my body shape. How many times do we unwittingly believe something about ourselves that is entirely untrue – based on false information or a false, distorted picture? Maybe someone has made a comment that made us think we are not good enough, or we compare ourselves with the images we see on social media that sometimes project a seemingly perfect life, and we tell ourselves we are not worthy of such things.

In my own life I’ve learned that the key to remaining undeceived by a lie is to begin with constant acknowledgment of what’s true about God and His creation. When I think about God, I think about love. “God is love,” the Bible declares. God’s love is bigger and deeper than human affection, it is ever present, unwavering, and all-inclusive.

In the first book of the Bible, it states that man – a generic term for men and women – is created in the image and likeness of God. And in her primary text, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Mary Baker Eddy, the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science, describes man as “the image, of Love,” and states elsewhere that the Bible tells us “God made man in His own image, to reflect the divine Spirit” (pp. 475, 516).

This idea that we are the reflection of God, divine Love – and not the reflection of anything else – is an anchor that each one of us can hold to in the midst of all the false images of individuality that we might be tempted to identify with.

Because we reflect God, good, divine Spirit, we must be wholly spiritual and good, worthy and loved. We simply must – it is inherent in our nature as reflection. And it doesn’t take effort to be a reflection. At the gym I see people lifting weights in front of the wall of mirrors. The reflection also appears to lift the weight, but it is effortless for that reflection.

So it is effortless for God’s children to reflect all that is good, which is all that is true about God. And our true nature reflects Love effortlessly, expressed in being gracious with others, having compassion, forgiving wrongs, or even having a love of life and all of our activities because we do them to glorify God.

I find the best way to know or feel the ever-presence of God’s love, and understand more clearly my true nature as a reflection of Love, is to just start loving, to just live love in all that I do. Looking for ways to be a blessing to others and being gracious and grateful when others bless us take thought increasingly off of self.

So now when I look in the mirror, I don’t worry so much about the image that is reflected back. Instead I read the quote I’ve taped to it – the verse from Science and Health that tells me I am “the image, of Love” – and think about how I can express love in all that I do that day.

What are you going to reflect today? As the image of Love, there’s truly only one option!

A message of love

Who are the suburban women?

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. And see you next week, when we'll look at U.S. voters feeling the burden of a high-stakes election amid anxiety over whether their votes will count.

And remember that you can find curated updates on breaking news in our First Look section.