- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Iran assassination: One of many attempts to box in Biden

- 2060 pledge: How the world’s largest CO2 emitter vows to go greener

- Love and the law: Hindu-Muslim couple challenges India’s marriage rule

- When your students are your workforce, what happens in a pandemic?

- Black women leaders find that ‘to be equal, you have to be superior’

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Kindness that covered 1,000 miles of wintry road

There’s going the extra mile for someone. And then there’s Gary Bath.

The Canadian Army Ranger’s recent act of kindness took him more than 1,000 miles out of his way. The story, which crossed my desktop this morning, blends far-north toughness with the kind of “Canadian nice” that we all might draw on as an example.

The odyssey begins with Lynn Marchessault, an American who needed to move her family and belongings from Georgia to where her husband is stationed as a U.S. Army staff sergeant in Alaska.

With her schedule disrupted by the pandemic, having a rugged pickup truck wasn’t enough for the onset of winter. At least not for someone unaccustomed to driving in snow – with two kids, two dogs, a cat, and a trailer in tow.

From losing traction to losing her way, the obstacles finally felt insurmountable. Yet, when Ms. Marchessault was at the point of breaking down emotionally, residents of a remote patch of British Columbia rallied around her. They helped her get better tires and a place to rest.

And when Mr. Bath learned on Facebook about the need, he decided he could offer something more: driving her the rest of the way.

“I am forever grateful to have met all of these kind strangers who helped us,” Ms. Marchessault wrote in an online post. Especially Mr. Bath. “We got along like old friends.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Iran assassination: One of many attempts to box in Biden

A high-powered campaign aimed at undermining the prospects for U.S.-Iran diplomacy may do little more than complicate President-elect Biden’s path.

Should President-elect Joe Biden return the United States to the 2015 multilateral Iran nuclear deal? Experts and former U.S. officials are publicly weighing in on the issue – both for and against – and to a degree not seen on other anticipated foreign-policy steps.

As Mr. Biden and his national security team have spelled out recently, Step 1 of a Biden plan would be a return to the deal, from which President Donald Trump withdrew in 2018, in exchange for Iran’s return to compliance. Step 2 would be a return to negotiations to address both the original deal’s sunset clauses and other destabilizing Iranian activities beyond the nuclear program.

But in the same vein as the dramatic daylight killing of Iran’s top nuclear scientist, sanctions the Trump administration has said it will continue to pile on Iran are seen as designed to steepen Mr. Biden’s path to the diplomatic initiative.

“Everyone right now, whether it’s Israel, whether it’s Iran, whether it’s the Trump administration itself, is in some way ... speaking to the Biden administration, and trying to either put it in a box, force its hand, or complicate its task,” says Robert Malley, a former Obama White House Middle East coordinator.

Iran assassination: One of many attempts to box in Biden

As President-elect Joe Biden considers his first foreign-policy moves upon taking office, perhaps none is garnering more attention – and coming under greater pressure – than his stated intention to return the United States to the Iran nuclear deal.

The recent assassination of Iran’s top nuclear scientist – unclaimed but bearing the hallmarks of an Israeli operation – is widely seen as aimed at poisoning the well that both the Iranian government and the new Biden national security team would draw from to renew diplomacy and fashion a return to the deal.

In the same vein as the dramatic daylight killing of nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh east of Tehran on Nov. 27 – an attack that reportedly included a satellite-operated, vehicle-mounted machine gun – the additional sanctions the Trump administration has said it will continue to pile on Iran until Jan. 20 are seen as designed to steepen Mr. Biden’s path to the two-part diplomatic initiative he envisions with Iran.

“Everyone right now, whether it’s Israel, whether it’s Iran, whether it’s the Trump administration itself, is in some way, whether its directly or indirectly, speaking to the Biden administration, and trying to either put it in a box, force its hand, or complicate its task ahead,” says Robert Malley, a former Obama White House Middle East coordinator.

And especially if these actions were to prompt retaliatory measures by Iran and provoke “an escalatory crisis, then yes, that would make a return to diplomacy under a Biden administration that much more difficult,” adds Mr. Malley, who is now president of the International Crisis Group.

As Mr. Biden and his national security team have spelled out in articles and speeches on Iran over recent months, Step 1 of a Biden plan would be a return to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, which the U.S. agreed to in 2015 along with five other world powers, in exchange for Iran’s return to compliance with the deal’s limitations on its nuclear program. President Donald Trump withdrew from the JCPOA in 2018, launching a policy of “maximum pressure” of ever-increasing sanctions on Tehran.

Step 2 would be a return to negotiations to address both the original deal’s sunset clauses and other destabilizing Iranian activities beyond the nuclear program: from ballistic missile development to support for regional proxies and groups the U.S. and others have deemed terrorist organizations.

Yet despite the high-powered campaign aimed at killing the prospects for diplomacy, no one seems to think that the efforts so far have done more than complicate the president-elect’s path.

One result is that former U.S. officials, nonproliferation experts, and Iran specialists are publicly weighing in on the issue – both for and against a return to the nuclear deal, and to a degree not seen on other anticipated foreign-policy steps.

Move fast! some counsel, warning that Iran’s moderates will be doomed in Iran’s presidential election next year if there is no U.S. return to the nuclear deal and accompanying sanctions relief. And if a hard-line candidate carries the day next June, they add, forget diplomacy.

No! Do not rush to give up the leverage the Trump administration will have bequeathed you, opponents of a return to the original JCPOA say. Continue to dangle the carrot of economic relief, they add, but don’t squander it in exchange for a return to limits on the nuclear program to which Iran already committed.

Iran deal skeptics worry that the Biden team will give away everything just to return to the Obama-era deal and to signal America’s return to multilateral diplomacy – retaining no leverage for the follow-on deal on Iran’s other regional activities that Mr. Biden says he wants.

“If they move prematurely on sanctions relief, what will they have left to deal on Iran’s broader bad behavior? Therein lies the conundrum of the incoming Biden administration,” says Behnam Ben Taleblu, a senior fellow focusing on Iranian security and political issues at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies in Washington.

“The last few blows of ‘maximum pressure’ the Trump administration is landing ought not to be traded away so easily as a way to facilitate diplomacy,” he adds.

The steady addition of new sanctions continued this week, as the U.S. Treasury on Tuesday blacklisted Iran’s envoy to Yemen’s Houthi rebels and designated the Tehran-based Al-Mustafa University for facilitating recruitment to the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, which the U.S. considers a terrorist organization.

Critics say front-loading sanctions relief as part of a deal returning the U.S. to the JCPOA would be akin to the U.S. agreement, as part of the original nuclear deal, to return hundreds of millions of dollars in frozen Iranian assets to the Iranian government. Iran used the windfall to ramp up its missile development program and its “nefarious” activities across the Middle East, these critics maintain, while giving little in return.

But proponents of a U.S. return to the deal counter that the commitments Tehran made (and largely kept) to reduce its nuclear activities succeeded in extending Iran’s “breakout” time to developing a nuclear weapon to over a year. Compare that, they say, to the estimated three-month breakout time Iran has achieved since once again ramping up its production of fissile material in response to the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the JCPOA.

Essentially Mr. Biden’s aim is to use a deal getting both the U.S. and Iran back in compliance with the JCPOA to put time back on the diplomatic clock – thereby paving the way for the more ambitious Step 2 of his Iran diplomacy plan. The Biden team is said to be thinking broadly in envisioning negotiations on Iran’s regional activities that could encompass the Gulf states, Saudi Arabia, and even Israel.

But such ambitious diplomacy would require a lot of time and would certainly run up against the political clocks counting down in the Middle East, regional experts say.

“There’s a very narrow window of time between Jan. 20 and elections in Iran in June, so what makes the most sense is an [initial] agreement to reduce tensions,” says Ilan Goldenberg, director of the Middle East Security Program at Washington’s Center for a New American Security. “You need to get something to stabilize the situation to work back from where we’ve been over the last few years.”

And then there’s Israel, and the growing prospects for another round of elections there in March or April.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has been perhaps the world’s biggest supporter of President Trump’s foreign policy, and has worked harder than any other foreign leader to undermine the JCPOA. The Fakhrizadeh assassination only adds to suspicions that Israel is doing what it can to torpedo Mr. Biden’s hopes of returning to diplomacy with Iran.

But some Israeli experts also suggest that Mr. Netanyahu will not want to enter elections totally on the outs with the new powers in Washington. Nor, they say, can he afford to ignore the sectors of Israeli society, including within the military, that do not consider the U.S. withdrawal from the nuclear deal and heightened U.S.-Iran tensions as good for Israel.

“There is no question the JCPOA is imperfect,” but the question for Mr. Netanyahu will be “is Israel better off with no JCPOA or an imperfect JCPOA?” says Shai Feldman, a former director of Middle East studies at Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts.

President Trump considered the nuclear deal “the worst agreement ever,” and Mr. Netanyahu concurred, “but it was not replaced by a different approach that … brought any significant fruits,” says Mr. Feldman, now president of Sapir Academic College in Israel. Except, he adds, that “four years later, Iran is closer to a nuclear capability.”

Some regional analysts say they take Mr. Biden’s two-step vision for negotiations with Iran as a good sign that the U.S. is not about to abandon the Middle East.

But Mr. Taleblu at the democracy foundation says he worries that U.S. fatigue with the region will prompt Mr. Biden to use up the sanctions leverage he inherits on getting a nuclear deal – and then will lose interest in addressing Iran’s destabilizing regional activities.

“There’s a structural trend to want to be done with the Middle East,” a trend that suits Iran just fine, Mr. Taleblu says. “My concern is that [the Biden team] will decide they’ve ‘solved’ the nuclear threat” with a quick deal “and won’t have the incentive to deal with the broader threats Iran poses to the region.”

The Explainer

2060 pledge: How the world’s largest CO2 emitter vows to go greener

2060 is a long way off. Will countries fulfill their recent pledges to go carbon neutral, or even climate neutral? Time will tell. But one thing is certain: Global climate efforts need China on board.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

One year ago, in a trailblazing move, the European Union vowed to become the first major economy to go climate neutral by midcentury. And in a less restrictive but widely welcomed commitment this fall, Chinese leader Xi Jinping followed the EU’s lead, vowing carbon neutrality by 2060. Japan and South Korea soon followed suit.

It’s a significant turnaround for Beijing, the world’s largest producer of carbon dioxide, which has long resisted restrictions on economic growth. And though China’s just one country, it could prove a significant step toward the global goal of reining in global warming.

“In the absence of Chinese cooperation, it would be very difficult to achieve the global carbon control efforts,” says Yanzhong Huang of the Council on Foreign Relations in New York. And the goal is attainable, he says, since China’s top-down, state-led approach to environmental controls – and Mr. Xi’s centralization of power – makes it harder for local officials to resist policies to reduce carbon.

But that’s not to say it’s a sure bet. The effort faces significant challenges: China’s reliance on coal, pressure to boost economic growth, and a lack of public pressure at home for tackling climate change.

2060 pledge: How the world’s largest CO2 emitter vows to go greener

In a surprise and widely welcomed pledge for the global environment, Chinese leader Xi Jinping committed in a speech to the United Nations in September that China would “achieve carbon neutrality” before 2060. Mr. Xi’s announcement came after pressure from European leaders and signaled a significant turnaround from Beijing’s long resistance to restrictions on economic growth. Whether China will reach its target remains uncertain. Yet experts say the pledge marks a major step in the world’s campaign to arrest climate change.

Why is China so critical?

China is the world’s largest producer of carbon dioxide, generating about 28%. CO2 accounts for about 80% of greenhouse gases, which trap heat in Earth’s atmosphere. Action from Beijing is essential to the goal of limiting global warming to 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit (1.5 degrees Celsius), as established by the 2015 Paris Agreement.

“In the absence of Chinese cooperation, it would be very difficult to achieve the global carbon control efforts,” says Yanzhong Huang, author of “Toxic Politics: China’s Environmental Health Crisis and Its Challenge to the Chinese State.”

Internationally, China’s pledge was followed by two other large Asian economies, Japan and South Korea, which both committed to carbon neutrality by 2050. All build upon the European Union’s trailblazing move a year ago, when it vowed to become the first major economy to go climate neutral, a step above carbon neutral that includes other greenhouse gases, by midcentury.

Beijing’s goal is attainable, Dr. Huang says, since China’s top-down, state-led approach to environmental controls – and Mr. Xi’s centralization of power – makes it harder for local officials to resist policies to reduce carbon. “As long as Xi remains committed ... disobedience and foot dragging should be very rare,” says Dr. Huang, senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York. Instead, he predicts, “local government officials will jump onto Mr. Xi’s policy bandwagon to demonstrate their enthusiastic support.”

Still, the effort faces significant challenges: pressure on leaders to boost China’s economic growth; ongoing reliance upon coal, the most carbon-intensive fossil fuel; and the lack of public pressure at home for tackling climate change.

How does Beijing plan to reach the goal?

Beijing has set an interim goal of reaching peak carbon emissions before 2030, followed by more aggressive measures to hit the 2060 target. Its strategy includes encouraging private investment in climate-friendly projects, reducing car emissions, and promoting electric vehicles. According to a recent government blueprint, by 2035 most of the country’s new cars will be either hybrids or new-energy vehicles.

“By 2025, China will be close to achieving peak emissions as a result of more ambitious actions to bolster renewables, pivot toward market mechanisms, and enhanced energy efficiency measures,” according to an analysis by MacroPolo, the think tank of the Paulson Institute in Chicago.

What are the main challenges?

One major obstacle is China’s longstanding reliance on coal power. Coal accounted for more than 57% of China’s energy use in 2019, and the country continues to operate and construct coal mines and build new coal-fired plants. “They actually issued more construction permits to coal-fired plants in the first half of this year than in [all of] 2018 and 2019 respectively,” says Dr. Huang. China’s carbon emissions increased in 2019 for the third year in a row.

“Dethroning coal won’t happen overnight,” MacroPolo senior research associate Ilaria Mazzocco writes in its report, saying coal industry officials argue coal is vital for China’s energy security. But she adds that Beijing is signaling changes, starting in 2021: freezing new power plant approvals, restricting coal power capacity targets, and other reforms to make renewable energy more attractive.

Political will poses another long-term challenge, Dr. Huang says. Although there is broad public support in China for controlling air pollution, Beijing lacks the kind of grassroots pressure to curb global warming that exists in Western democracies. While China’s authoritarian leaders have the final say, their agenda can shift because “their legitimacy is primarily dependent on their ability to deliver robust economic growth,” he says. It is “very difficult for them to transcend the dilemma between economic growth and environmental protection.”

Love and the law: Hindu-Muslim couple challenges India’s marriage rule

Concerns about intolerance in India have been mounting for years. But in the face of fear and prejudice, some interfaith couples are speaking up to celebrate their love and try to smooth the path ahead for others.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Sarita Santoshini Correspondent

After nine years of dating, Nida Rehman and Mohan Lal were ready to wed. But a problem still stood in their way: Ms. Rehman is Muslim, and Mr. Lal Hindu. And today in India, interfaith marriages often draw scrutiny, or worse.

Her parents disapproved, but Ms. Rehman was adamant. If you want to marry a good person, she believed, faith shouldn’t stand in the way. “Religion does not create boundaries like these,” she says.

This fall, they were finally married. Yet she’s also brought a legal challenge to provisions in the law governing interfaith unions, which critics say is both discriminatory and dangerous, given the harassment and violence many couples have faced. It comes at a time of rising tensions over the legal rights of Muslims in this Hindu-majority democracy.

Officially, India remains a secular country in which a couple like Ms. Rehman and Mr. Lal are free to marry.

But “the concept of secularism in India is understood as each existing peacefully within their own homes,” says Asif Iqbal, co-founder of Dhanak of Humanity, the nonprofit that supported Ms. Rehman. “We are not mentally prepared to exist together within the same home yet.”

Love and the law: Hindu-Muslim couple challenges India’s marriage rule

In September, as India relaxed its lockdown restrictions, Nida Rehman made the difficult decision to leave her parents’ home. COVID-19 cases were still on the rise. But living with her family, she had come to conclude, posed a bigger risk to the life she wanted to lead.

For nine years, Ms. Rehman, a Muslim woman, had built a relationship with Mohan Lal, a Hindu man whom she met at university. But her family’s position was clear: She could not marry outside her faith, and they would find her a Muslim match themselves.

Ms. Rehman was adamant. If you want to marry a good person, she believed, faith shouldn’t stand in the way. “Religion does not create boundaries like these,” she says.

So she moved out, with the help of a nonprofit, and registered to marry Mr. Lal. Within days, she had filed an urgent legal petition to the Delhi High Court, challenging provisions of a federal law that she and other petitioners say is both discriminatory and dangerous for interfaith couples in India who face harassment and violence.

Her challenge to these provisions in the law governing interfaith unions, the Special Marriage Act, comes at a time of rising tensions over the legal rights of Muslims in this Hindu-majority democracy.

Last month India’s largest state Uttar Pradesh introduced a controversial law against what right-wing Hindu groups call “love jihad,” an alleged Muslim conspiracy to woo and convert Hindu brides. Police made their first arrest last week under the law, which carries a maximum penalty of 10 years in prison, of a Muslim man accused of trying to lure a married Hindu woman. Several other states are preparing similar legislation, though a court-ordered probe by India’s National Investigation Agency into dozens of interfaith marriages found no evidence of coercion. Earlier this year, India’s home affairs minister confirmed that no such cases have been registered by central agencies.

Under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), India has become increasingly polarized along communal lines. Last February, riots in neighborhoods around Ms. Rehman’s home in northeast Delhi left 53 people dead and thousands displaced, most of them Muslim. Tensions had been building for weeks, as millions across the country protested the passage of an act granting citizenship to non-Muslim migrants from neighboring countries – the first time Indian law has used religion as a basis for citizenship.

Critics say the BJP government’s exclusionary use of citizenship laws and its targeting of interfaith marriages are part of a political scapegoating of India’s estimated 200 million Muslims.

Officially, India remains a secular country in which a couple like Ms. Rehman and Mr. Lal are free to marry.

But “the concept of secularism in India is understood as each existing peacefully within their own homes,” says Asif Iqbal, co-founder of Dhanak of Humanity, the nonprofit that supported Ms. Rehman. “We are not mentally prepared to exist together within the same home yet.”

A risky choice

Only 5% of Indian marriages are between people of different castes, according to the Indian Human Development Survey from 2011-12; estimates from the 2005-06 survey suggest that an additional 2.2% are interfaith. Moreover, in a culture where arranged marriages are the norm, only 5% of women said they had sole control over choosing their husbands.

“In the Indian perspective, the right to choose is itself a big question. Religion and caste are just alibis to stop them,” says Mr. Iqbal.

Any couple can register under the Special Marriage Act as an alternative to religion-specific laws. The pair must first provide a district marriage registrar with names, home addresses, and photographs, which are then displayed in the registrar’s office for 30 days. Anybody who wants to file an objection can do so, though the grounds are specific: For example, neither partner should have a living spouse, be underage, or be incapable of consent due to “unsoundness of mind.”

This may sound innocuous. But the publishing of personal details puts interfaith couples at risk of public opprobrium, family arm-twisting, or worse.

Women who defy their family and community are often the victims of honor-based violence. India recorded 288 cases of honor killings between 2014, when it started to track the practice, and 2016. In some cases, men are victims: In 2018, Ankit Saxena, a Hindu man, was stabbed to death in New Delhi, allegedly by the relatives of his Muslim girlfriend.

This summer, the government in the southern state of Kerala decided to stop publishing applications online after vigilante groups spread more than 100 registered couples’ details on social media, warning of “love jihad.” Some other states continue to post interfaith marriage applications online.

Facing such risks, many couples choose to convert and marry instead under religious law.

Ms. Rehman’s petition describes the 30-day notice as “a breach of privacy” that “jeopardizes [couples’] life and liberty.” A separate petition to the Supreme Court, filed in August by a law student, challenges the same provisions in the 1954 law. Two years ago, the Law Commission of India urged reforms, including to the practice of publicizing couple’s personal information and of registrars contacting their parents. “It is important to ensure that at least, willing couples can access the law to exercise their right to marry when social attitudes are against them,” it wrote.

Utkarsh Singh, a lawyer representing Ms. Rehman, notes that couples who marry within a faith don’t face a 30-day notice period. “You don’t put religious marriages to such tests but only interfaith marriages,” he says, arguing that once couples file the necessary paperwork they should be allowed to marry whenever they choose.

“This narrative is not new,” says Noorjehan Safia Niaz, a founding member of the Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan, which advocates for Muslim Indian women’s rights, in reference to increasing prejudice. What is new, she says, is that “with the political climate being conducive that they [Hindu nationalists] are so open and blatant about it.”

Sharing their story

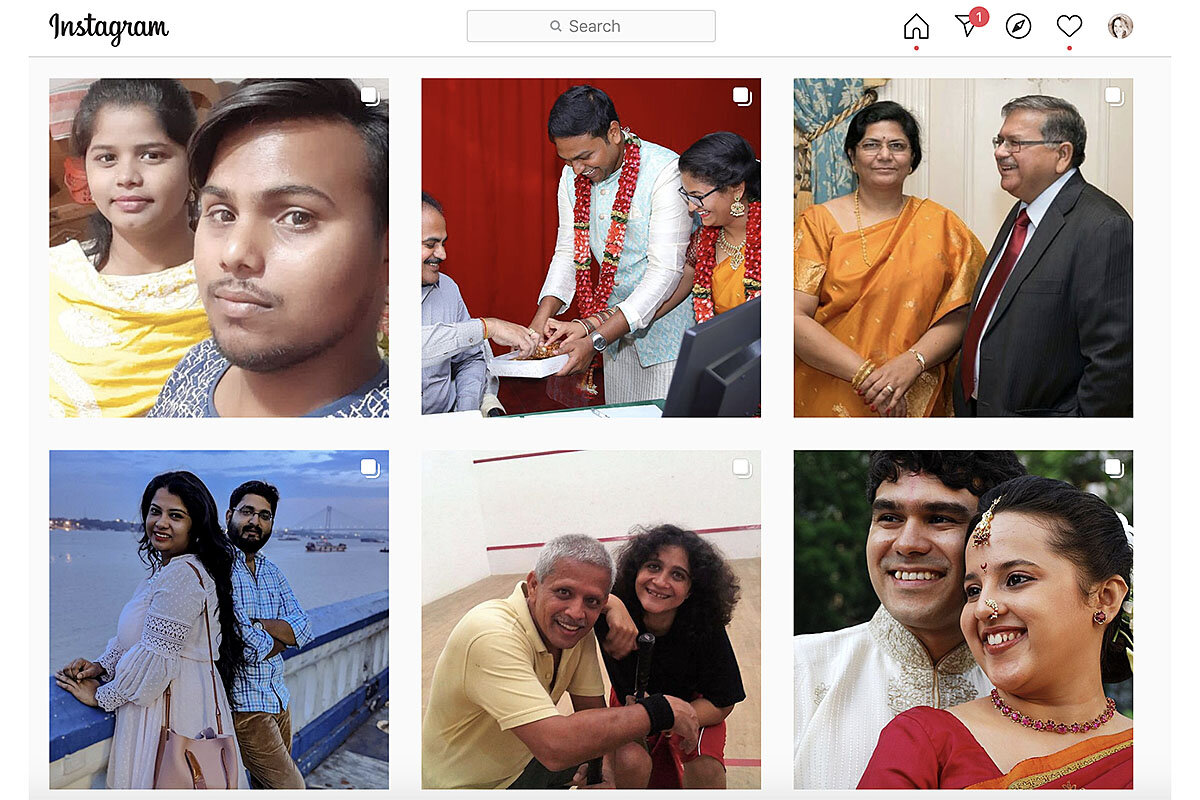

Some Indians are coming forward to counter these narratives – and not just in court. Three editors recently started the India Love Project, an Instagram feed of portraits of “love outside the shackles of faith, caste, ethnicity, and gender.”

The idea was to create space for couples to “share their stories, inspire others like them, and simply make all of us feel good about love,” says co-founder Samar Halarnkar. “What better way to counter something that is fake than with something that is real.”

Nonprofits like Dhanak of Humanity continue to offer support, such as safe houses. In 2018, the Supreme Court ordered that special police units be formed in every district to assist couples who feared for their lives, but they are not yet a reality in most parts of the country.

On Oct. 28, Ms. Rehman and Mr. Lal were finally married. Celebrations kicked off with a small gathering of couples Dhanak of Humanity has supported. The next morning, the bride’s friend hosted a Hindu haldi ceremony, when turmeric paste is applied to the bride and groom.

That afternoon, witnessed by five friends, the couple were officially wed at a marriage office, and celebrated over lunch at a mall – the kind of simple, intimate wedding Ms. Rehman had always wanted.

Their legal fight continues. The Delhi high court has asked the federal and Delhi governments to file a response to Ms. Rehman’s petition; the next hearing is scheduled for Jan. 15. The goal, she says, is to smooth the way for couples after them.

Meanwhile, she’s pursuing a bachelor’s degree in education, while preparing for the civil service exam. Mr. Lal works as a pharmacist. “Every night he returns home from work and asks what I studied that day, eager to discuss it with me,” Ms. Rehman says.

Now that they live together, they enjoy cooking and reading together. “In fact,” she adds, “we enjoy doing everything together.”

When your students are your workforce, what happens in a pandemic?

For work colleges, where students are partially responsible for maintaining campus operations, the pandemic has posed unique challenges. It has also reinforced the importance of everyone pitching in.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

“There’s a value in a hard day’s work,” says Allison Southard, director of development at Alice Lloyd College in Kentucky. The school is one of nine colleges in the U.S. where students do many of the jobs – from farm work to fundraising – that keep the campus running. The goal is to keep costs down for both students and the administration.

That’s tricky in a pandemic, though, when disruptions to student work programs lead directly to disruptions in campus operations.

“We had to shift to a work program where we were covering the essential jobs first,” says Lyle Roelofs, president of Berea College, also in Kentucky. “It was sort of amusing,” he says, recalling one student who was originally planning to work in the fundraising office but wound up “being asked to explore the dignity of labor by feeding the hogs.”

Yet even with the upheaval caused by the pandemic, freshman Kelli Thomas considers Berea the perfect college for her. Coming from a family with no income, she’s grateful to pay nothing and have no debt. “I’ve always wanted to go to Berea,” she says. “I knew that if I didn’t get to go here, then I probably wouldn’t get to go anywhere else.”

When your students are your workforce, what happens in a pandemic?

Edgar Ortiz pauses as he operates a wooden loom several times larger than he is, reflecting on his college job as he fashions a place mat.

“Who comes to college and learns how to weave?” he asks.

For Mr. Ortiz, a chemistry major set to graduate this spring, weaving place mats wasn’t how he originally imagined he’d be spending his time outside the lab. But Mr. Ortiz attends Berea College, where every student is assigned a job on campus, ranging from farm work to artisanal craft skills – such as weaving or woodworking – to more routine posts such as cleaning or being a teaching assistant.

This past semester, though, Mr. Ortiz was missing more than half of his co-workers. Social distancing rules had limited the capacity of the weaving studio and the number of students able to work there. On a recent afternoon, he was joined by only one other student employee and their supervisor, who is overseeing seven students this year instead of her usual 16 to 18.

Students at work colleges like Berea – there are eight others in the United States – are employed by the school in an effort to keep costs down for both students and the administration. Working through the pandemic has meant adjusting to new health standards and working in smaller, socially distanced crews – if students are able to work at all. And for the colleges, disruptions to the student work programs lead directly to disruptions to day-to-day operations.

“We had to shift to a work program where we were covering the essential jobs first,” says Berea President Lyle Roelofs. This was especially true in agriculture, where the college’s crops and livestock needed diligent care, but there were fewer students on campus to provide it. “It was sort of amusing,” he says, recalling one student who was originally planning on working in the fundraising office but wound up “being asked to explore the dignity of labor by feeding the hogs.”

The value of work

Some work colleges trace their roots as far back as the 1800s, though they were not officially designated as such by the federal government until the early 1990s. From a financial perspective, work colleges employ their students as a way to cut down on the costs of running a school. Students are either paid directly or have their earnings applied to the balance they owe the college. But there’s a philosophical underpinning to the work programs as well.

“There’s a value in a hard day’s work,” says Allison Southard, director of development at Alice Lloyd College in Pippa Passes, just 120 miles from Berea. By working, students “are invested in their own education,” she adds.

For Sylvia Asante, Berea’s dean of labor, the work program helps build more well-rounded students. “So, they’re not saying, ‘Oh, I want to go to med school.’ And that’s it,” she says. “You can go to med school. But guess what? You could still be a farmer.”

At Paul Quinn College in Dallas – distinct in that it’s an urban work college and a historically Black school – many students “come from backgrounds of long-term unemployment or long-term underemployment,” explains Michael Sorrell, president of the college. Officially becoming a work college under his leadership in 2017 gave the school “an opportunity to stand in the gap,” he says.

Of course, it’s easier to “stand in the gap” when students are actually on campus.

The ripple effect of remote learning

In a year that saw publicly traded shares in Zoom skyrocket, work colleges were at a disadvantage when it came to remote learning, since they often serve students from poor and rural backgrounds who may have limited access to the internet. This made Alice Lloyd’s abrupt switch to online classes in the spring especially difficult.

Having fewer students on campus had big ramifications for operations as well. A small workforce continued through the summer, with only about 30 students on campus to earn extra money – and keep the college running – versus the usual 100 or so. “We had some staff who were picking up on things that they wouldn’t normally do,” says Ms. Southard. “Everybody pitched in and did what needed to be done.”

This fall, Alice Lloyd’s full student body (just under 600) returned to in-person classes, which also shored up the college’s workforce – at least when students weren’t in quarantine.

At Paul Quinn, classes were offered exclusively online this fall. The indoor farm was maintained by a skeleton crew due to social distancing and safety measures, and some students found themselves unemployed. But that didn’t mean President Sorrell let them off easy. Students who weren’t able to work on campus or at their internships were enrolled in a course to build soft skills as well as greater fluency in Microsoft Office products.

Berea opted for a hybrid model this past semester, and 50% of the student body chose to take classes from home. Of that group, some were able to work remotely, but overall the college’s workforce was down about 600 to 700 students. And after in-person instruction ended with the start of Thanksgiving break, most students left campus and aren’t slated to return – or start working again – until the start of spring term.

“I think it was actually a positive experience for our students to realize that when work needs to be done, everybody’s got to do their part,” says Dr. Roelofs, Berea’s president. “And by and large, we had excellent morale, given the sacrifices people were making.”

Making college possible

Even with the upheaval caused by the pandemic, freshman Kelli Thomas, who stayed on campus this fall, still considers Berea the perfect college for her. Hailing from Floyd County, Kentucky, where 34% of the population lives in poverty, she comes from a family with no income. At Berea, thanks to the school’s endowment and its work program, she pays nothing and has no debt. “I’ve always wanted to go to Berea ever since I was in middle school,” she says. “I knew that if I didn’t get to go here, then I probably wouldn’t get to go anywhere else.”

As for Mr. Ortiz, the chemistry major, he plans to use his degree to work in the cosmetics industry or as a tutor. And in his free time?

“I might want to invest in a loom myself and start making my own products,” he says. If nothing else, he’ll have a hobby to keep himself busy if society still remains largely homebound come summer.

Editor’s note: As a public service, we have removed our paywall for all pandemic-related stories.

#TeamUp

Black women leaders find that ‘to be equal, you have to be superior’

Our new #TeamUp column will cover racial equity, foreign policy, the arts, and more. It kicks off exploring what it’s like to be the only one of your race and/or gender in the room – a position our Emmy Award-winning columnist knows all too well.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Jacqueline Adams Correspondent

In my careers in journalism and business, nonprofit work and education, I have often been the only woman or the only Black person in the room – certainly the only Black woman. That never surprised me.

My first conscious memory is of my father saying, “When you’re Black in America, to be equal, you have to be superior.” I thought to myself, “Is that all it takes?”

From excelling in school to becoming an Emmy Award-winning broadcast journalist, I traded superior achievement for equal treatment.

But despite often being the “only,” I am not alone. Across industries, Black women leaders know “only-ness” all too well – along with the built-in stressors that come with it.

And yet, Black women are indomitable. Harvard Business Review found that women of color are three times more likely to aspire to a position of power with a prestigious title than white women. Ironically, white women are about twice as likely to attain that position of power.

What’s the answer? Women of color can and are “teaming up.” And you can join us. Keep an eye out for this #TeamUp column, devoted to issues of racial equity, social justice, foreign policy, and the arts.

Black women leaders find that ‘to be equal, you have to be superior’

How often are you the only person of your gender or race in a professional setting? Do you even notice? Have you ever asked yourself this question?

In this season of recognizing social and racial injustices, the question is relevant. And there’s lots of data on the subject.

Truth be told, in my careers in journalism and business, in my decades of experience in nonprofit work and education, I have often been the “only.” When I was a copy kid at The Christian Science Monitor almost a half-century ago, I was an “only.” And I barely noticed.

It is only now, as I call up a sepia-toned mental image of my Monitor posse and bosses, that I notice they were all white and male, among them the publisher and his son. They were my friends. Many of them continued working at the Monitor. But I had other ambitions and was able to fulfill them.

I became an Emmy Award-winning broadcast journalist with CBS News. I traveled the world, reporting on Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. When I moved to New York City, I described my CBS beat as “mayhem and the arts.” I covered major criminal trials and business news for “CBS Evening News with Dan Rather” as well as a series of French Impressionism and 20th-century African American art exhibits for “CBS Sunday Morning.”

I lost touch with my friends who built their careers at the Monitor. Relentlessly, perhaps blindly, I pursued my own goals of success and achievement.

And now, I have come home to the Monitor to begin a new role as a columnist, somewhat more observant than I was as a copy kid.

A toxic standard

My first conscious memory is of my father saying, “When you’re Black in America, to be equal, you have to be superior.” Yes, that standard is impossibly, needlessly high. But I didn’t resent my father’s insistent message. I said to myself, “Is that all it takes?” The world’s standard is, and was, just a passing grade. When you’re a child, school is your job. What else was more important than working a little harder to get superior grades?

And my grades were superior! That empirical data gave me confidence. And that confidence propelled me, sustained me, in all of the rooms in which I was – and even today, at times, remain – an “only.”

Why does the standard have to be so high? It doesn’t. But that standard – and the racial bias implicit in it – can be toxic. Both demand a response.

Securing a seat at the table

For our newly published book, “A Blessing: Women of Color Teaming Up to Lead, Empower and Thrive,” my co-author, Bonita C. Stewart, and I conducted a survey of 4,005 female American “desk workers.” As far as we know, our Women of Color in Business: Cross Generational Survey is the first to look at four races (Black, Latina, Asian, and white) and four generations (boomers, Gen X, millennials, and Gen Z).

We found that 47% of Black women – almost half – said they are frequently or always the only person of their race in professional situations. By contrast, 73% of white women said they are rarely the only person of their race in such a setting.

We also found that 31% of Black women said their job applications are viewed more skeptically. The number is almost twice that reported by white women (17%). A recent McKinsey & Co. survey of racial equity in financial services confirmed the finding, even beyond the financial industry: “Black job applicants with degrees from elite universities experience the same résumé response rate as white applicants with degrees from state colleges.”

“We are the miraculous”

Once Black women cross the application hurdle and are hired, their “only-ness” comes with built-in stressors. We found that twice as many Black women as white said their work is viewed skeptically (35% of Black women, 23% Latina, 17% Asian, 16% white). And a number of surveys have found that women of color face more microaggressions than white women. Their judgment is questioned in the workplace, and even senior women are mistaken for support staff.

And yet, Black women are indomitable – even in the face of scrutiny, stress, and aggressions, both micro and macro. Harvard Business Review research has quantified our unbridled ambition with the finding that women of color are three times more likely to aspire to a position of power with a prestigious title than white women. Ironically, white women are about twice as likely to attain that position of power.

What’s the answer? Women of color can and are “teaming up.” And you can join us. As an example, Black, Latina, and Asian American alumnae at Harvard Business School have held their first joint “sisterhood circles,” providing inspiration, psychological support, and concrete advice for individuals facing specific challenges. As poet Maya Angelou wrote, “We are the miraculous.”

This #TeamUp column is the first in a series devoted to issues of racial equity, social justice, foreign policy, and the arts. Stay tuned.

Jacqueline Adams is co-author of “A Blessing: Women of Color Teaming Up to Lead, Empower and Thrive."

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A critical aspect of the vaccination campaign

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In a high note for medical history, Margaret Keenan in the United Kingdom became the first person in the world (outside of a clinical trial) to receive the COVID-19 vaccine made by Pfizer-BioNTech on Dec. 8. For many health professionals, however, she was just as important for another reason – her mental attitude.

“There’s nothing to be afraid of,” she told the BBC. “I’m over 90 years old, and I had no doubt.”

Ever since the devastating 2014-16 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, global health experts have put a new focus on ways to alleviate public fear and mistrust of both vaccines and the health care establishment. Much of the work against Ebola had been hindered by high levels of distrust. In response, the World Health Organization set up an independent body, the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board, to look at “the human dimensions of health security,” or what’s also called “design thinking.”

An effective vaccination campaign relies on more than a vaccine. Health officials must first understand their communities and the values of each individual. Such tender care is good medicine, lifting people’s thought to be active participants in any health emergency.

A critical aspect of the vaccination campaign

In a high note for medical history, Margaret Keenan in the United Kingdom became the first person in the world (outside of a clinical trial) to receive the COVID-19 vaccine made by Pfizer-BioNTech on Dec. 8. For many health professionals, however, she was just as important for another reason – her mental attitude.

“There’s nothing to be afraid of,” she told the BBC. “I’m over 90 years old, and I had no doubt.”

Ever since the devastating 2014-16 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, global health experts have put a new focus on ways to alleviate public fear and mistrust of both vaccines and the health care establishment. Much of the work against Ebola had been hindered by high levels of distrust among local communities, even feelings of being victimized by health services. In response, the World Health Organization set up an independent body, the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board, to look at “the human dimensions of health security,” or what’s also called “design thinking.”

In its latest report since the coronavirus pandemic began, the board concluded this: “In many countries, communities are an afterthought, rather than at the center of preparedness, and governments and public health authorities have defaulted to one-way, directive communications rather than developing collaborative approaches that involve communities, leading to a disconnect between national messages and local contexts.”

And to add a finer point, it made a prediction: “How the world emerges from this crisis will depend on whether and how countries, actors and communities overcome their unwillingness to work together.”

That report was echoed in the United States by a study out of Johns Hopkins University in July. Titled “The Public’s Role in COVID-19 Vaccination,” the study made this stark assessment: “Much is still unknown about what the diverse U.S. public knows, believes, feels, cares about, hopes, and fears in relation to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines.”

It suggested the health community shift its attitude in how to administer the coronavirus vaccine: “What does the person on the receiving end think, expect, experience, and sense about the valued good intended for him or her?” Greater listening to individuals will help reduce what the health industry fears – “vaccine hesitancy.” The public’s sense of safety, the report stated, extends beyond health matters.

This attention to the mental climate of a health crisis is not new. Florence Nightingale, the famed 19th-century nurse pioneer, advised nurses to attend to a patient’s thinking as much as to the body. “How very little can be done under the spirit of fear,” she said.

An effective vaccination campaign relies on more than a vaccine. Health officials must first understand their communities and the values of each individual. Such tender care is good medicine, lifting people’s thought to be active participants in any health emergency.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Peace amid disappointment

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Karen Neff

If a certain outcome feels unjust, and disappointment follows, we can seek recourse to a higher authority.

Peace amid disappointment

How could this be? I couldn’t believe what my husband was telling me. He hadn’t gotten the expected promotion at his job. It was a given that he would. Everyone expected it. After all, he was the senior man, the most experienced, and the most qualified. Yet the promotion had gone to another. How unfair!

However, after a momentary pause of incredulity, I found myself calming my thought and turning to God. My husband and I quickly agreed that this simply meant something better would come along. We started to feel a deep and meaningful peace.

According to Christian Science, two names for God are Truth and Love, which means God is just and merciful. For us this meant that even when faced with what seems like an unjust outcome and the anger and disappointment that ensue, we have recourse to a higher authority.

This doesn’t mean praying from a selfish standpoint and just asking for help with something we think has been lost or taken from us. It simply means letting go of our own human sense of things and trusting God’s goodness. In “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” the discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, writes: “Love is impartial and universal in its adaptation and bestowals. It is the open fount which cries, ‘Ho, every one that thirsteth, come ye to the waters’” (p. 13).

Disappointment can’t last long when we make it a consistent practice to look to the higher power of God that governs our life. The Bible speaks of God in this way: “Justice and judgment are the habitation of thy throne: mercy and truth shall go before thy face” (Psalms 89:14). In God’s kingdom there can be no letdowns – there’s only God’s law of equity and benevolence operating on our behalf. Perceiving this truth frees us of any disappointment or discouragement.

The confidence and freedom my husband and I were feeling in God’s leading also stifled any sense of animosity or retaliation we might have been tempted to feel. To my husband’s credit, he continued to do his job to the very best of his ability, even helping his new boss navigate through the process of taking on new responsibilities. There was no rift in their relationship, either, and they remain friends to this day.

Soon the bigger picture became clear to us – my husband realized he could take an early retirement, and this felt like a right next step. We had no idea what he would do for work, since he was at an age when companies might consider him “over the hill,” and this was a factor we had to consider. But continuing to feel guided by God, he did retire.

Seventeen days from the day he retired, he was offered a position within a company that for many years he had dreamed of working for. We never could have foreseen this coming about, and he spent another 13 happy years doing what he truly loved, made new friends, and earned another retirement.

Mrs. Eddy wrote, “Justice waits, and is used to waiting; and right wins the everlasting victory” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 277). When events and plans don’t work out in the way we had anticipated, it’s not impossible to be unafraid and undisturbed. The key is to continue trusting God to unfold goodness and progress. If we wait unafraid, the way forward will always come to light – and we will thrive!

Some more great ideas! To read or listen to an article in the weekly Christian Science Sentinel on hearing God's voice in a way we can understand titled “God’s unique messages,” please click through to www.JSH-Online.com. There is no paywall for this content.

A message of love

Delicious urban planning

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. We’ll be back tomorrow with a look at how America’s judicial system is holding up, amid unprecedented efforts by a sitting president to overturn election results.