- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Trump has asked judges to overturn election. So far, all have declined.

- As pandemic surges, where do ‘frontliners,’ business owners find hope?

- State-sponsored assassination: New tools, old questions

- How Arkansas district used solar power to boost teacher pay

- He doesn’t know it, but he’s in my book club

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

‘If I can do it, you can do it’: How first ‘Kid of the Year’ tackles problems

Kim Campbell

Kim Campbell

What will the next generation of problem-solvers look like?

We got a sense of that this past week when Gitanjali Rao, a 15-year-old from Colorado, was named the first “Kid of the Year” by Time magazine and TV’s Nickelodeon.

What makes this inventor, scientist, and mentor (to 30,000 students and counting) stand out is not only her work to identify contaminants in water or detect cyberbullying through a service called Kindly. It is her attitude: She extols failure as a path to success, recognizes that the field of science needs to include more diversity, and encourages others to act on causes they are passionate about.

In 2017, then-staff writer Amanda Paulson interviewed her for the Monitor. Besides the teen’s intelligence and thoughtfulness, she recalls Gitanjali as someone “who truly cares about making the world a better place.”

The way Gitanjali sees it, solving the world’s problems will take people recognizing their own inner innovators. “It’s not easy when you don’t see anyone else like you. So I really want to put out that message: If I can do it, you can do it, and anyone can do it,” she tells actor and Time contributing editor Angelina Jolie.

Tonight, Time will unveil its “Person of the Year” on a special broadcast on NBC. The finalists are Joe Biden, Donald Trump, front-line health care workers and Dr. Anthony Fauci, and the movement for racial justice.

One day soon, Gitanjali may end up on that list, too.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Trump has asked judges to overturn election. So far, all have declined.

Conservatives have long expressed concern about “activist judges” legislating from the bench. That may be why some of the most scathing rulings against attempts to overturn the election have come from Federalist Society judges and Trump appointees.

In dozens of similar cases brought before state and federal courts the past five weeks, judges reacted with incredulity at the claims Republican lawyers brought before them, and the sheer audacity of their efforts to disenfranchise millions of American voters.

One still remains at the Supreme Court: The state of Texas filed a lawsuit against the states of Pennsylvania, Georgia, Michigan, and Wisconsin, each of which certified their tallies in favor of President-elect Joe Biden, asking the Supreme Court to toss out the votes of millions of Americans and directing their respective legislatures to choose their slates of electors instead. Legal experts say it is likely to meet the same fate as the other lawsuits.

In a Wisconsin case nearly identical to the Texas lawsuit, conservative state Supreme Court Justice Brian Hagedorn, a member of the Federalist Society, expressed alarm at the arguments his fellow Republicans were making, calling the desired outcome of nullifying the entire presidential election unprecedented and “the most dramatic invocation of judicial power I have ever seen.”

“Something far more fundamental than the winner of Wisconsin’s electoral votes is implicated in this case,” Judge Hagedorn wrote. “At stake, in some measure, is faith in our system of free and fair elections, a feature central to the enduring strength of our constitutional republic.”

Trump has asked judges to overturn election. So far, all have declined.

After 35 days of defeat after defeat in state and federal courts, President Donald Trump and his chorus of allies lost their 50th post-election lawsuit on Tuesday.

It was the latest of a furious five-week but so far futile legal effort to convince American judges across the nation to nullify millions of votes in six key states and declare President Trump the winner of the 2020 presidential election.

There was a certain symmetry, if not irony, in the president’s 50th loss on Tuesday, also the electoral “safe harbor day.” A feature of a dusty 19th-century law that set a deadline of sorts for lingering election disputes, the 1887 act requires Congress to count the electoral votes of states that certified their elections six days before the Electoral College meets. All but Wisconsin met that deadline, with one more case being heard Thursday.

In a terse one-sentence ruling, the United States Supreme Court, whose conservative majority will provide President Trump with one of his most enduring legacies and remains the last-gasp legal hope of those still fighting to keep the president in office, denied a Republican appeal to throw out Pennsylvania’s election. Mr. Trump and his supporters have a success rate of one minor win out of, as of Thursday, 56 rulings in cases they filed.

While it’s all but certain that the electors meeting next Monday will reflect the will of the states that chose them, the curtain has not quite been drawn on the five-week opera of American politics in the time of COVID-19, and the president’s leitmotif of election fraud.

The state of Texas filed a lawsuit against the states of Pennsylvania, Georgia, Michigan, and Wisconsin, each of which certified their tallies in favor of President-elect Joe Biden, asking the Supreme Court on Tuesday to toss out the votes of millions of Americans and directing the states’ respective legislatures to choose their slates of electors instead.

Joined by six other Republican states, the Texas lawsuit argues that since the Constitution only vests state legislatures with the authority to appoint presidential electors, any governor or state official who issued any COVID-19-related changes to election procedures would have violated the Constitution. Seventeen Republican attorneys general signed an amicus brief, and President Trump has requested to intervene in the case.

Such unconstitutional procedural changes during the pandemic, including expanded mail-in voting and extended deadlines, the Texas lawsuit also alleges, only served to relax these states’ ballot-integrity measures, triggering what it says was a host of voting irregularities and fraud.

On Thursday, 20 states, two territories, and the District of Columbia filed an amicus brief siding with the four battleground states, asking the court not to overturn the election, saying, “The people have chosen.”

Legal experts say the Texas lawsuit will meet the same fate as the other 55 failed lawsuits Republicans brought to state and federal courts over the past five weeks. For one, the lawsuit is specifically targeted to battleground states that gave a total of 62 electors to Mr. Biden. But Republican Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, too, issued executive orders “suspending certain statutes” governing the election, and extended ballot deadlines. States that joined the Texas lawsuit, including Kansas and Mississippi, also issued orders allowing mail-in ballots arriving late to be counted, even as they argue such orders in the four battleground states were unconstitutional and dangerous triggers of voter fraud.

“But hypocrisy aside, the suit is also a perfect microcosm for so many of the other cases we’ve seen filed in the past month,” wrote Steve Vladeck, professor at the University of Texas School of Law, about the Texas-led effort to invalidate millions of votes. “It is lacking in actual evidence; it is deeply cynical; it evinces stunning disrespect for both the role of the courts in our constitutional system and of the states in our elections; and it is doomed to fail.”

In dozens of similar cases brought before state and federal courts the past five weeks, judges reacted with incredulity at the claims Republican lawyers brought before them, and the sheer audacity of their efforts to disenfranchise millions of American voters.

“It’s not just Democrats who are calling these suits garbage,” says Wilfred Codrington III, professor of law at Brooklyn Law School in New York. “It’s been across the board. And I’d say that the most emphatic examples that sum up what has been going on with these lawsuits have been Republican judges.”

Conservative judges weigh in

In a Wisconsin case nearly identical to the Texas lawsuit, conservative state Supreme Court Justice Brian Hagedorn, a member of the Federalist Society and former chief legal counsel to former Republican Gov. Scott Walker, expressed alarm last week at the arguments his fellow Republicans were making.

“[The] real stunner here is the sought-after remedy,” Judge Hagedorn wrote. “We are invited to invalidate the entire presidential election in Wisconsin by declaring it ‘null’ – yes, the whole thing. And there’s more. We should, we are told, enjoin the Wisconsin Elections Commission from certifying the election so that Wisconsin’s presidential electors can be chosen by the legislature instead, and then compel the Governor to certify those electors.

“At least no one can accuse the petitioners of timidity,” Judge Hagedorn added, noting such a remedy – a court-ordered disenfranchisement of every Wisconsin voter – would appear to be unprecedented in American history. “This petition falls far short of the kind of compelling evidence and legal support we would undoubtedly need,” he said of the Republican arguments, which were full of “glaring flaws that render the petition woefully deficient.”

In Pennsylvania, a panel of three Republican-appointed judges in the 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals, including Judge Stephanos Bibas, a member of the Federalist Society appointed by President Trump, also emphatically rejected an appeal argued in person by former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani.

“Free, fair elections are the lifeblood of our democracy,” Judge Bibas wrote. “Charges of unfairness are serious. But calling an election unfair does not make it so. Charges require specific allegations and then proof. We have neither here.”

Even so, the Republican team led by Mr. Giuliani was seeking a “breathtaking” invalidation of millions of votes. “Its alchemy cannot transmute lead into gold,” Judge Bibas wrote. “The [Trump] Campaign never alleges that any ballot was fraudulent or cast by an illegal voter. It never alleges that any defendant treated the Trump campaign or its votes worse than it treated the Biden campaign or its votes. Calling something discrimination does not make it so.”

Crumbling GOP trust in elections

In public, however, Mr. Giuliani, part of the president’s self-described “elite strike force” legal team, has promised to unleash a torrent of evidence that would reach “biblical” proportions. Reverting to a more pagan analogy, lawyer Sidney Powell also famously said that she would “release the Kraken” with a four-state lawsuit that would once and for all expose widespread election malfeasance and justify tossing millions of votes in states that voted for Mr. Biden. All four of those suits have failed.

“There’s this gap between the specific arguments they’re making – or not making – in court, and the reception of the public arguments they’re presenting in public,” says Claire Finkelstein, professor of law and at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School. “So there’s this broader phenomenon of a large percentage of that 70 million people who voted for Donald Trump being actually convinced that the Democrats and Joe Biden have stolen the election from Donald Trump.

“But by bringing lawsuit after lawsuit after lawsuit, the GOP and Donald Trump are trying to make it look as though there really is a legitimate question about whether or not Joe Biden won the election,” says Professor Finkelstein. “And that maybe is part of an overall strategy that we’ve seen the GOP use all through the nearly four years of Donald Trump’s presidency, which is to cast confusion and doubt over things that are quite clear, so that everything seems to exist in a kind of haze of law and facts, and you don’t really know at any point sort of what happened or what’s allowed.”

An overwhelming 72% majority of Republicans, in fact, say they do not trust that the 2020 election results were accurate, according to an NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist survey. Two-thirds of independents and 95% of Democrats say they do trust the results.

And only 27 congressional Republicans out of 249 in the House and Senate have publicly acknowledged Mr. Biden’s 7 million popular vote margin and convincing electoral victory in last month’s elections, The Washington Post reports. The majority simply will not say.

On Tuesday, three Republican members of the Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, and Senate Rules Committee Chairman Roy Blunt, also refused to acknowledge Mr. Biden’s victory.

At stake: faith in American democracy

Still, Republican state election officials and other local GOP lawmakers have maintained that their elections were among the most trouble-free in recent years. Federal cybersecurity officials in the Trump administration have said the election was the most secure ever conducted. And Attorney General William Barr, a Trump loyalist, has said investigators have found no evidence of widespread fraud.

Neither has a single state or federal court over the past five weeks, despite the fact that the Trump campaign and other Republicans have had chance after chance to present evidence to support their claims – or their widely proposed remedy to disenfranchise millions of voters and have Republican legislators select state electors instead.

The sheer emptiness of the audacious and unsupported claims, Wisconsin’s conservative Supreme Court Justice said, “compelled” him to offer one last observation at the end of his decision to reject one of the more than 50 lawsuits Republicans have filed.

“Something far more fundamental than the winner of Wisconsin’s electoral votes is implicated in this case,” Judge Hagedorn wrote. “At stake, in some measure, is faith in our system of free and fair elections, a feature central to the enduring strength of our constitutional republic.

“It can be easy to blithely move on to the next case with a petition so obviously lacking, but this is sobering,” he continued. “The relief being sought by the petitioners is the most dramatic invocation of judicial power I have ever seen. ... This is a dangerous path we are being asked to tread. The loss of public trust in our constitutional order resulting from the exercise of this kind of judicial power would be incalculable.”

A deeper look

As pandemic surges, where do ‘frontliners,’ business owners find hope?

The coronavirus outbreak has inflicted an emotional toll that can extend to what’s known as moral injury. Many people are seeking the perspective – and the human connections – to address a hope deficit.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Amid a new surge of coronavirus cases, many front-line workers and others are facing a toll that’s emotional and mental as well as physical.

Where does a person find hope? From emergency rooms to retail shops and virtual classrooms, some common answers involve building human connections and managing expectations.

“We’re continuing to demand as much of ourselves as we did before – to be the perfect parent, the perfect worker, the perfect student,” says Wendy Dean, a psychiatrist and co-founder of a nonprofit group supporting health care workers. “People have to find a way to have forgiveness for themselves and recognize that they’re doing the very best they can.”

Dr. Jessica Lu in Seattle uses remote calls with her nursing-home patients to help alleviate their social isolation. Patients can sometimes help her, too. After Dr. Lu asked a few questions of one younger patient, the woman flipped the script. “Hey, Dr. Lu,” she said, “how are you doing?”

“What I think the pandemic has shown above all is you have to take care of each other,” Dr. Lu says. “We’re all connected.”

As pandemic surges, where do ‘frontliners,’ business owners find hope?

A public defender in San Diego marvels at the resolve of her clients. A doctor in Providence, Rhode Island, draws strength from the stamina of her emergency room colleagues. A bookstore owner in Minneapolis gives thanks for the loyalty of his customers. A middle school teacher in Los Angeles cherishes the enthusiasm of her students.

Nine months into the coronavirus pandemic, as the number of cases soars, the economy sputters, and everyday life refuses to come unstuck, they face the same obvious yet complicated question that shadows each of us: Where does a person find hope?

Their answers, if varying in details, revolve around the common theme of connection. Our daily interactions – deprived of spontaneity and typically filtered through masks, Zoom, or both – remain a source of reassurance as the uncertain present lurches toward a blurred future.

“There is a sense of being in the foxhole together,” says Dr. Megan Ranney, an emergency physician at Brown University in Providence, referring to her fellow health care workers. “It sometimes feels like we’re in a war for our patients and for ourselves. That tightens the bond.”

Still, even for the most resilient among us, persevering week after week in our socially distant existence poses a struggle as another round of stay-at-home orders hits several states. The country’s vast political divide further inflames our grievances as officials at every level send conflicting messages about the pandemic, giving rise to personal distrust and, at times, public animosity.

The damage inflicted to the spirit and a loss of faith in others can contribute to people experiencing moral injury. Mental health experts describe the condition as a “wound to the soul” that exhausts an individual’s emotional reserves and provokes intense doubts about life’s worth.

Editor’s note: As a public service, we have removed our paywall for all pandemic-related stories.

Mending that internal rupture requires a deliberate effort to reassess our expectations and search for purpose as we await the post-pandemic era, says Dr. Wendy Dean, a psychiatrist and co-founder of the nonprofit group Moral Injury of Healthcare.

“All of us have the need to feel normal,” she says. “But we’re continuing to demand as much of ourselves as we did before – to be the perfect parent, the perfect worker, the perfect student. People have to find a way to have forgiveness for themselves and recognize that they’re doing the very best they can.”

Bearing witness

Dr. Ranney has learned to downshift from the 18-hour workdays she pulled during the early months of the outbreak. Yet as cases spike again, the vitriol aimed at doctors and nurses by those who question the severity of the disease – or its existence – marks an unsettling contrast to spring, when the country united in lauding front-line responders.

“It’s a very dark, difficult time for health care workers, who are working at the edge of their physical and emotional capacity,” she says. More than 1,400 providers have died from the coronavirus, and thousands more have chosen to leave the profession. “It sometimes feels like we’re the Little Dutch Boy. We’re trying to keep our finger in the dike to stop that dam from breaking – and now we’re having tomatoes thrown at us and being told we’re making this up.”

Moral injury, a term most often linked to veterans of military conflict, occurs when individuals commit, fail to prevent, or witness an act that violates their ethical beliefs, or when those in positions of authority betray their trust. The behavioral, emotional, or psychological toll that lingers can at once distort self-identity and sow suspicion or disdain of others.

A new report from National Nurses United examines risk factors for moral injury among medical providers as the pandemic drags on. The list includes inadequate preparation by and support from government agencies and health care employers, lack of social support, and emotional trauma related to the deaths of patients.

Beyond the failures of public and hospital officials, the backlash from large numbers of Americans and limits on hospital visits deepen the plight of providers, who act as proxies for the loved ones of patients stricken by the virus.

“The feeling of betrayal is one thing,” Dr. Dean says. “But there’s also this feeling of ‘I can’t do it all. I can’t pull this train by myself.’ We’re asking them to take care of people where prevention has fallen short – and in some cases has been ignored – and we’re also asking them to bear witness for all of us.”

Dr. Ranney seeks to ease her unseen burdens through public advocacy and private diversions. She serves as a medical analyst for CNN, offering insight into the hardships of front-line responders, and works with Get Us PPE, a nonprofit she co-founded that provides free personal protective equipment to medical organizations.

The mother of two young children, she exhales at home by watching “The Mandalorian” with her son and “Gilmore Girls” with her daughter, and by taking occasional turns on the family trampoline. Weekend hikes with her husband and kids allow her to briefly slip free of anxiety’s orbit.

The perils and pressures of work aside, Dr. Ranney nurtures a cautious optimism, encouraged by the prospect of a vaccine and a cohesive pandemic plan from President-elect Joe Biden. “This is the most urgent public health crisis of our time,” she says. “I’m honored I get to do what I do. It is an absolute privilege.”

“We’re all connected”

A similar sense of dedication and gratitude sustains Dr. Jessica Lu, a third-year family medical resident at University of Washington Medicine, a health care network in Seattle. Many of her patients live in nursing homes, and while safety measures preclude in-person visits with most of them, Zoom calls enable her to alleviate their social isolation.

“From the beginning of the pandemic, I’ve recognized how fortunate I am to do the job I’m doing,” she says. “That kind of satisfaction keeps me going.”

Dr. Lu holds measured hope that the country’s ordeal might persuade coronavirus skeptics to discard “brute individualism” as a public health policy. “What I think the pandemic has shown above all is you have to take care of each other,” she says. “We’re all connected.”

A recent exchange with a patient illustrated that principle in an unexpected way. She asked a few questions of the young woman, who answered all of them – and then flipped the script. “Hey, Dr. Lu,” she said, “how are you doing?”

Her evident sincerity touched the doctor. “Every day I’m looking for one good thing that happens, one little kernel of joy,” she says. “That’s how we get through this.”

Methods of coping

Tatiana Kline abides by the ethos of empathy in her role as a deputy public defender in San Diego. The pandemic prevents her and her colleagues from meeting with clients, who languish behind bars as courts delay hearings and trials, increasing their risk of exposure. An estimated 227,000 inmates in jails and prisons nationwide have contracted COVID-19, and nearly 1,600 have died.

“The biggest hurdle is not having face-to-face access to our clients,” she says. Most of her conversations with them now occur via video conference and phone calls. “You miss having that personal touch – shaking hands, looking them in the eye – because that helps make them feel human in a system that doesn’t treat them that way.”

When Ms. Kline realized earlier this year that colleagues shared her frustration, she started a virtual wellness program, creating a space for them to discuss their concerns and methods for coping. The conversations serve to reaffirm their devotion to aiding clients, most of whom live along the socioeconomic margins, and she intends to continue the program after the office reopens.

“Almost everybody feels like they’re in limbo right now,” she says. “This is a way to help us keep going forward and advocating for the people we represent.”

The virtue of persistence

A desire to persist motivates Jamie Schwesnedl, who with his wife, Angela, owns Moon Palace Books in Minneapolis. The shop stands a block from a police station that rioters burned down in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death at the hands of officers on Memorial Day.

During the demonstrations, Mr. Schwesnedl and his employees posted a large sign in the store’s upper windows that read “Abolish The Police,” a signal of their support for the community. Moon Palace escaped the charred fate of dozens of nearby businesses that remain in ruins, and the neighborhood has rallied to the shop’s cause. The Schwesnedls, while forced to cut their staff from 41 to 12, have weathered the dual blows of the pandemic and protests on the strength of online sales and takeout orders from the store’s cafe.

“People with small businesses are asking themselves, ‘Should I keep doing this or should I completely reevaluate my life?’” Mr. Schwesnedl says. He laughs before adding, “But you don’t have a chance to think about it because you’re trying to keep your business afloat.”

Beneath his dark humor lies an economic horror story. One recent study found that more than 420,000 small businesses closed nationwide between March and mid-July. A Harvard University database shows that 29% of the country’s small businesses have shut down since January.

Mr. Schwesnedl knows that, without healthy holiday sales and new federal stimulus funding, Moon Palace might join the ranks of defunct bookstores. “But we’re doing what we love,” he says, “and the idea that things could improve in 2021 has helped keep us going.” He laughs again. “Besides, what are the options?”

Facts and imagination

His cleareyed outlook aligns with Michele Levin’s view on adapting to pandemic upheaval. She teaches science to seventh- and eighth-graders at Daniel Webster Middle School in Los Angeles, and since switching to online classes, she has found her students more attentive and engaged. At the same time, the discretion of private messages has reduced their reluctance to share personal troubles with her, giving her a chance to enlist counselors or tutors when necessary.

“What I’ve seen with being online is that it’s a very equal setting that’s less scary for a lot of them,” she says. “It’s helping build their confidence.”

Early research into remote learning draws less promising conclusions, with studies suggesting that online instruction could magnify disparities in academic performance and cause students to lose as much as 12 months of learning by the end of this school year.

Ms. Levin, a teacher for more than three decades, understands that the pandemic presents academic and emotional obstacles for her students. When they raise questions about the outbreak, she tends to respond with answers grounded in science, discussing progress on a vaccine or the public health rationale for wearing masks.

On other occasions, if she detects a collective unease, she might propose a virtual group hike to soothe their anxieties, and the class will set off online through a forest or along a river.

Her approach – with students and to life – balances a trust in the primacy of facts with an awareness of the solace that imagination provides. “I know from a science standpoint that things will get better,” she says, “and I have an innate optimism that things will get better.”

Now she’s just waiting for the science to catch up with the optimism.

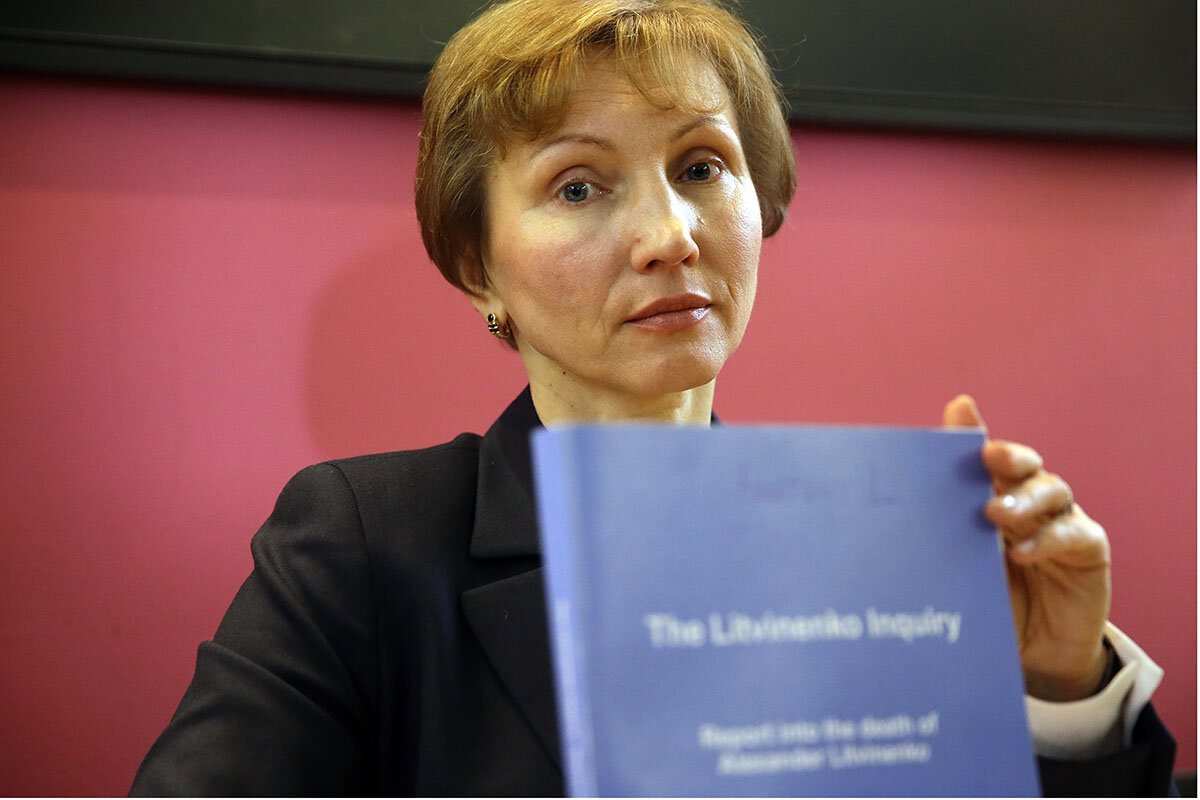

State-sponsored assassination: New tools, old questions

State-sanctioned assassination appears to be back in fashion. But as nonstate actors too acquire drones for “targeted killings,” will that convince the great powers to think again?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

By Ned Temko Correspondent

Last month, somebody assassinated Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, a top Iranian nuclear scientist. It was almost certainly the Israelis, but it marked only the latest in a string of “targeted killings” by nations such as the United States and Russia.

Assassination has a long history; 2,500 years ago, the Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu recommended picking off enemy generals. Nine hundred years ago, the Hashishiyyun, agents of a minority Muslim sect, used the tactic against rival rulers.

But toward the end of the 19th century, the leading powers moved to outlaw assassination. That was not – or not only – because they thought it the right thing to do. It was because assassination had become a common tactic of the underdog – a weaker state or a disaffected individual – in order to level the odds.

Today, that is again the case. Islamic State is believed to be able to use armed drones in the same way U.S. forces do, for example. In Venezuela, amateurs rigged up explosive drones with components they bought on the internet in order to launch an assassination attempt against President Nicolás Maduro.

It may be that if such capabilities continue to spread, the major powers may once again decide that tolerating, and using, assassination is not in their interests.

State-sponsored assassination: New tools, old questions

It was over within seconds: a hail of gunfire amid the hills and orchards east of Tehran. Yet last month’s deadly strike against a key figure in Iran’s nuclear program has roots stretching back 2,500 years, to an ancient struggle for supremacy in China – and future implications going well beyond its effects on today’s Middle East.

For the attack on Mohsen Fakhrizadeh was the latest sign that assassination (“targeted killing” in modern military parlance) – a practice shunned internationally and legally proscribed for over a century – is finding official favor again and making a comeback.

And where once the assassin may have wielded simply a sharp knife, today he might use space-age technology. According to the latest Iranian account of the attack on Mr. Fakhrizadeh, almost certainly carried out by the Israelis, he was killed by a truck-mounted machine gun. But no one fired it, Iran said. It was operated by remote control via satellite, using facial recognition technology to confirm they had the right man.

Advances in military technology, such as drones and other remote-control weaponry, have made targeted killings easier for all sorts of actors, not only sophisticated national armies.

The nature of war, too, has changed: Since the 2001 Al Qaeda attack on the twin towers in New York, conflicts between countries have given way to a more nebulous “war on terror” against nonstate groups.

Whether a new age of assassination has dawned depends on a tangle of thorny questions. Some are familiar, such as the ethical and legal issues behind past international prohibitions of such attacks: the need to avoid injuring civilians, for instance, or to demonstrate a compelling military reason for striking. There are also questions as to whether such attacks actually achieve their aim, or lead to unintended and unforeseen consequences.

Yet looking ahead, it might be an entirely different and more practical concern that prompts any international moves to put new legal guardrails in place. The technology that governments use to target individuals for assassination is increasingly easily available to those individuals for use against governments.

Still, so far there seems no sign the trend is abating.

This may have something to do with the rise of nationalism and the weakening of international alliances and institutions.

That could help explain why old-style attacks by authoritarian regimes against their own rivals or dissidents have also been getting so brazen in recent years. Russia has used the deadly chemical polonium and a military-grade nerve agent against former security-service officers living in Britain, and gunned down a former insurgent from Chechnya in a Berlin park. North Korean agents employed a nerve agent to kill a half-brother of dictator Kim Jong Un in the departure hall of Kuala Lumpur International Airport in Malaysia.

To understand the resurgent use of assassination – and the readiness of once-reticent Western powers like the United States to employ it – you need to look at how the practice got started more than 2 1/2 millennia ago, how it spread, and how it ultimately fell into international disfavor.

In ancient China, the tactic was seen not so much as a tool of all-out war, but as part of a prudent leader’s strategy to avoid a costly, protracted struggle against a powerful rival. That was the context in which the Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu – in his famous tract “The Art of War” – advocated using spies to locate and kill an enemy’s key commanders and his lieutenants.

Over the centuries, assassination attacks became a common tactic around the world, used by leaders of weaker forces – or insurgents, or disaffected individuals – in order to level the odds against more powerful rivals. Their frequency in 15th -century Italy, including the so-called Pazzi Conspiracy against the Medici family’s rule in Renaissance Florence, figured in Niccolo Machiavelli’s “The Prince.” No fewer than five of pre-Soviet Russia’s emperors were assassinated.

Little surprise, then, that it was the established powers which moved in the latter part of the 19th century, to ban assassinations. That consensus hardened after World War I, a conflict sparked by the 1914 assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand by a Serbian nationalist. After World War II the Geneva Conventions barred the killing of anyone not directly involved in combat.

As American academic Audrey Kurth Cronin pointed out in a fascinating article on state-sanctioned assassination early this year, in the journal Lawfare, major governments wanted to outlaw assassination not just because they believed it was “the right thing to do; it was how modern nation-states consolidated their power.”

Yet that consensus has been unravelling – and nowhere more so than in the region that the latest Tehran attack has propelled back onto the front pages: the Middle East.

The very term “assassin” originated in what is now Iran. In the 1100s, a minority sect of Islam, seeking to expand its influence, organized knife-wielding squads to kill rival leaders. These units were known as the Hashishiyyun, from their reputation for using hashish before setting off on missions.

This weak-versus-strong equation also helps explain Israel’s venture into targeted killings in the 1970s. The country was surrounded by Arab states with large, well-armed standing armies, which rejected its very existence as a state, while also facing a challenge from Palestine Liberation Organization guerrillas.

The immediate catalyst was the attack by the PLO’s “Black September” faction on Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics. For years afterward, special Israeli units tracked down and killed dozens of Palestinians whom the Israelis held responsible for the Olympic assault and other attacks. A desire for punishment and revenge was surely a factor in the campaign. But Israelis involved in it have insisted that the main aim was more defensive and future-focused: deterrence.

Israel’s widened use of targeted killings since the early 2000s might also have made sense to Sun Tzu as a hedge against all-out war.

Wars have broken out anyway, against the Islamist Hamas government of Gaza, and Iranian-armed Hezbollah militia forces across the northern border in Lebanon. But by killing individual Palestinian military figures in Gaza, and more than a dozen people involved in the nuclear program inside Iran, Israel has sought to forestall more complicated, boots-on-the-ground conflicts.

The calculation for the Americans has been similar, especially in light of widespread reluctance among voters and politicians of both parties to send U.S. troops into major combat since the 2003 Iraq War.

Advances in military technology have encouraged Washington to rely more often on targeted killings of Al Qaeda and Islamic State leaders, and others. Some of those attacks have caught the public’s attention and stirred legal and political debate, not least because of the frequent risk of civilian casualties in such operations.

But much of the information about such attacks, especially those involving America’s Central Intelligence Agency, has been held back. Widespread attention and public scrutiny have been limited largely to the deaths of major figures such as Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden at the hands of special operations forces, and Qassem Soleimani, commander of Iran’s military forces in Syria, Lebanon, and elsewhere in the Middle East, killed by a drone-launched missile.

Hundreds of other drone strikes on individuals deemed dangerous by the U.S. have gone almost unnoticed. Barack Obama brought U.S. troops home during his time in office, but he sought to minimize the impact of their withdrawal by authorizing some 500 drone operations.

Speaking to The Atlantic near the end of his second term, he said he had come to realize “the dangers of a form of warfare that is so detached from what is actually happening on the ground.” He had therefore initiated moves to implement internal “checks and balances.”

Not long before leaving office, he also issued an executive order requiring the release of information on the number of civilians killed in such attacks outside combat zones. But President Donald Trump rescinded the order last year, and has overseen a fresh surge in deadly American drone attacks.

Though such operations are permitted under U.S. domestic law, even the Trump administration, despite its resistance to international oversight of American actions, still seems sensitive to long-held standards such as the Geneva Conventions and other rules of conflict. After General Soleimani’s assassination – which occurred in Iraq, a country with which the U.S. is not at war – officials argued that it was a necessary act of self-defense, given his role in an alleged imminent attack against Americans.

The United Nations’ top investigator of extrajudicial killings rejected that argument on the grounds that there was “insufficient evidence provided of an ongoing or imminent attack,” which meant that the assassination breached international law.

It seems unlikely, in the current international climate, that legal or political pressure could rein in assassination as a tactic. More persuasive, perhaps, is the fact that the U.S., its European allies, and Israel are not alone in their ability to deploy new technology. Iran can deploy armed drones too, as can its Houthi allies fighting in a civil war in Yemen. Islamic State forces appear to have formed a unit equipped with drones capable of delivering explosive charges.

In a particularly dramatic sign of how accessible such capabilities are becoming, a CNN investigation found that opponents of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro built the explosive drones that swooped in on him during a high-profile public address in 2018 from a kit bought from a U.S. supplier on the internet. The attempt on Mr. Maduro’s life failed, but only because the explosive charge detonated a few seconds prematurely.

In other words, the proliferation of assassination could once again enable less powerful states, and nonstate actors, to level the odds against more powerful adversaries. Not for the first time in assassination’s controversial history, the self-interest of major powers may prove to matter most in deciding its future.

Points of Progress

How Arkansas district used solar power to boost teacher pay

This is more than feel-good news – it's where the world is making concrete progress. A roundup of positive stories to inspire you.

How Arkansas district used solar power to boost teacher pay

1. United States

In the spring, Midshipman Sydney Barber will become the first Black woman to serve as brigade commander – the highest post for a midshipman – at the U.S. Naval Academy in Maryland. In the nearly five decades that women have been allowed to attend the academy, only 15 others have achieved this rank. One colleague calls the mechanical engineering major and track team member a “catalyst for action, a visionary, a listener, a doer, and a person driven by compassion.”

Midshipman Barber says she looks forward to continuing to break glass ceilings and making her family proud. When talking to NPR about her great-grandparents, who were sharecroppers on a Mississippi plantation, Ms. Barber said, “They would never even picture this moment. This America looks nothing like the America that they experienced. ... I always take that to heart.” (NPR, Yahoo News)

2. United States

A school district in Arkansas has joined the thousands of educational institutions across the country embracing solar energy – and it’s using savings to boost teachers’ pay. The Batesville School District used to operate on a $250,000 budget deficit and struggled to retain teachers. During a 2017 audit, school leaders discovered the annual utility bill was more than $600,000. By installing solar panels and updating the facilities to be more energy efficient, the schools cut their yearly energy consumption by 1.6 million kilowatts and are on track to save $2.4 million over 20 years. That’s translated into raises averaging $2,000-$3,000 per educator. Batesville was able to secure a $5.4 million bond to make the updates, but in 2019, Arkansas passed legislation designed to support other districts making a similar switch. (Energy News)

3. Costa Rica

Costa Rica affirmed its commitment to combating modern slavery by signing a 2014 United Nations treaty, which requires states to identify, rescue, and compensate victims of forced labor and punish human traffickers. In 2017 the U.N. estimated 40 million people are in forced labor and forced marriages, including 6,000 people in Costa Rica. Traffickers often target women, children, and migrants, who can be sold for sex or trapped in agricultural or domestic servitude. The U.N. International Labor Organization says Costa Rica is the fifth country in Latin America and the Caribbean to sign the treaty, and it brings the U.N. closer to its goal of ending modern slavery in the next decade. (Thomson Reuters Foundation)

4. Pakistan

A new project in Karachi is creating a cleaner and more inclusive city by establishing the nation’s first privately managed public restrooms. The social welfare group behind the initiative, the Salman Sufi Foundation, says its focus is on the safety of women, people with disabilities, and the transgender community. About 40% of Pakistan’s population lack access to decent toilets, according to the charity WaterAid, and previous efforts by the government to maintain functional restrooms have been stymied by restrictive city budgets. Under the new approach, the Salman Sufi Foundation has been able to build each wheelchair-accessible bathroom out of old shipping containers for $12,700. The facilities are well lit and ventilated, and also include baby-changing stations. Mohammad Hanif works in a cargo office near the group’s inaugural toilet, and said that it’s a huge improvement: “I had little choice but to use the stinky and perpetually wet public toilet a little further away from here. This one is like using a five-star facility.” (Thomson Reuters Foundation)

5. New Zealand

New Zealand Police has added the hijab to its official uniform options – a move the police force hopes will help officers better reflect the country’s diversity and encourage more Muslim women to join the force. Police officials say they began developing a uniform hijab in 2018, and new recruit Constable Zeena Ali will be the first to don the garment. She also had a hand in designing the hijab. Constable Ali says she decided to join the force after the Christchurch shooting in 2019 that killed 51 people and injured 40 who were worshipping in two mosques. “I realized more Muslim women were needed in the police, to go and support people,” she told the New Zealand Herald. “It feels great to be able to go out and show the New Zealand Police hijab as part of my uniform.” (BBC, The New Zealand Herald)

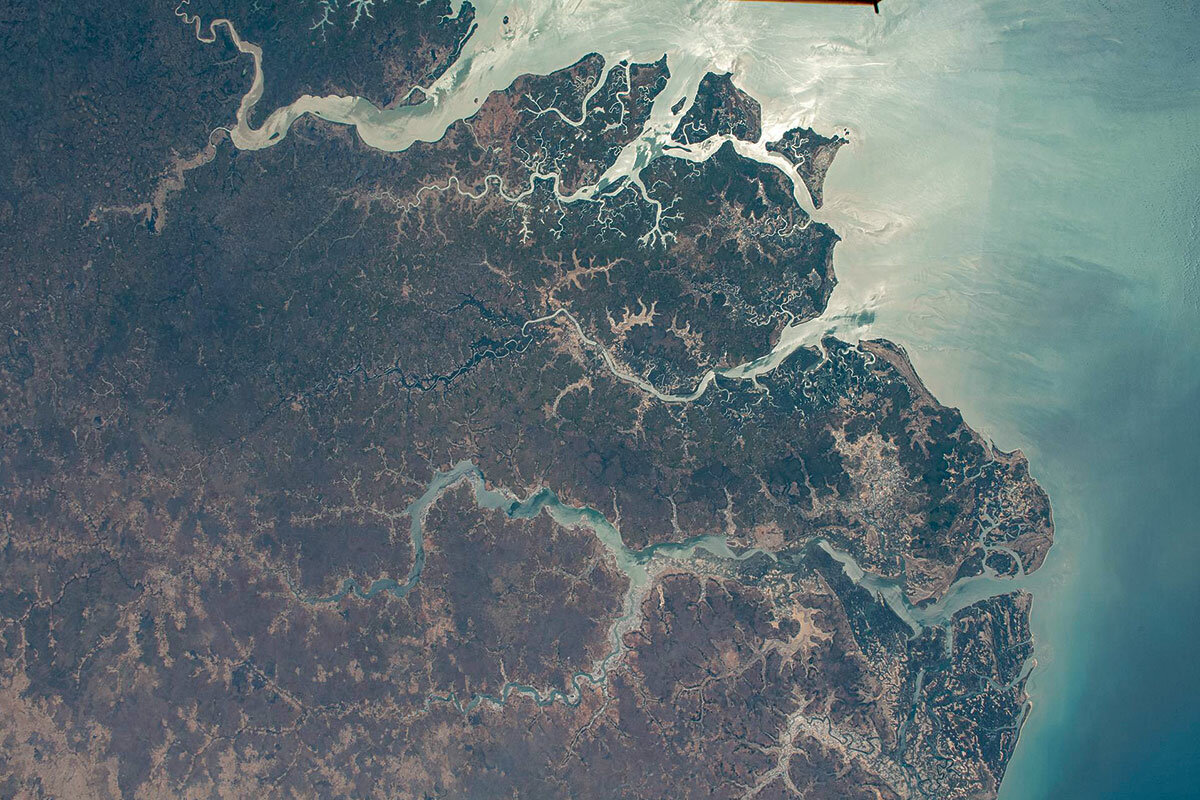

Outer space

For the first time, NASA has used supercomputers and AI technology to map nonforest trees from outer space. The international team of scientists surveyed 500,000 square miles in dryland regions, including the Sahara’s arid south, discovering billions of trees in just a few weeks. Traditional methods of mapping trees growing outside forest boundaries could have taken years to produce the kind of data NASA’s team was looking for.

Their findings mark the first in a series of studies to determine how much carbon nonforest trees store. “There are important ecological processes, not only inside, but outside forests, too,” said Jesse Meyer, a programmer at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “For preservation, restoration, climate change, and other purposes, data like these are very important to establish a baseline.” (SciTechNews)

Essay

He doesn’t know it, but he’s in my book club

Reading is a silent and solitary activity, but readers of the same book are often eager to share opinions and suggestions. What if that, too, were done silently?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Jaqi Holland Correspondent

I first saw him while we were on jury duty. He was reading an obscure memoir by an Australian humorist.

I spotted Jury Duty Guy again a month later on a subway platform in Boston. This time, he had one of my favorite books, “Mountains Beyond Mountains,” by Tracy Kidder. Again, I was impressed.

And with that, an unspoken book club was born.

He was at the same spot on the platform for years. I’d take his book of the week as a tacit recommendation, and soon I’d be reading it across from him. His occasional lapses into summer bestsellers felt like a betrayal: Put down that mainstream drivel, I wanted to yell.

But it wasn’t his fault. He didn’t know we were in a book club.

Later, I saw him at a taco spot downtown. I wanted to catch up as if we were old friends. But when he finally sat down at the counter, he’d already cracked a hardcover, and I didn’t want to interrupt. Book club was in session.

He doesn’t know it, but he’s in my book club

When a neighbor asks if I’m in a book club, I’m not sure how to answer. “Yes,” I say. “And no.”

Our book club of two formed organically years ago when I saw a bookish, 40-something man sitting across from me in jury duty in Concord, Massachusetts, reading “My ’Dam Life,” an obscure memoir by Australian humorist Sean Condon about his experience living in Amsterdam.

When I moved to chat with this fellow bookworm, we were ordered to watch a video on the justice system and foiled again when we filed into the courtroom to hear a case. Jury duty, often an opportunity for a solid reading session, can also call you away at inopportune times. We parted that day without speaking.

A month later, I was standing on a Boston subway platform and saw Jury Duty Guy across from me reading one of my favorite books, “Mountains Beyond Mountains.” Again, I was impressed: more quality nonfiction and a commitment to social justice, or at least to the strong writing of Tracy Kidder. With that, our unspoken book club was born.

I saw Jury Duty Guy at that same spot for years, always around 5:15 p.m. and always with a book. As we waited for the train to Alewife, I’d steal glimpses of the cover to see if it was another quality book with a curious title or meaningful story – to make sure he was still in the club.

I took his book of the week as a tacit recommendation, and it wouldn’t be long until I stood across from him reading the same book. When I saw him with “A Little Life” by Hanya Yanagihara, I knew it was a gem. No commuter would carry that tome unless it was unputdownable. A double endorsement: He’d take it out of his beat-up satchel to read despite the flashing LCD sign indicating that the train would arrive in three minutes, time enough to enjoy only a few paragraphs.

At times, he’d have that summer’s bestseller – one year it was “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo” by Stieg Larsson – and I’d wonder why he was reading such a pedestrian book. We’d connected in spirit, at least in my mind, because of our niche reading tastes. This was a betrayal! Put down that mainstream drivel, I wanted to yell, and pick up that new novel about a button collector or the antelope that reads people’s minds.

It wasn’t his fault. He didn’t know we were in a book club.

Or did he?

One day I spotted him reading “Nice Big American Baby” by Judy Budnitz, a quirky short story collection I’d read a few months earlier. We were back together! But had he gotten that title from me? Did he know about our book club?

I may never know. I moved, my commute changed, our book club dissolved.

I still worked in the city, though, and he did, too. I saw him one day at a taco spot downtown. I was flustered. I wanted to catch up as if we were old friends, and I really wanted to know what he was reading. The line was long; there was time. But when he finally sat down at the counter, he’d already cracked a hardcover, and I didn’t want to interrupt him. Book club was in session.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

College football’s resourceful rehuddle

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

College football in the 2020 season has become a time to expect the unexpected. And against a backdrop of sobering statistics related to the pandemic, these games have offered a welcome expression of vitality and exuberance.

Teams that normally schedule opponents years in advance suddenly have been looking around from week to week to find a quick game with a team not sidelined by COVID-19 precautions.

A quick glance at the top contenders might suggest business as usual: Perennial powers Alabama, Notre Dame, Clemson, and Ohio State top the list. On the flip side are the amazing upstarts, who are treating their fans to unexpected successes.

If 2020 is teaching anything in sports, it’s that keeping things flexible isn’t as impossible as previously thought.

Another lesson is that playing through the pandemic – with all due precautions – seems to have brought players and coaches even closer. At Indiana, for example, the upstart team’s slogan is “LEO” – love each other.

That’s one good effect on athletes in any season – not just the surreal one of 2020.

College football’s resourceful rehuddle

College football in America often comes with surprises, but the saga of Rice University’s season symbolizes just how unprecedented this year has been. The team was unable to play seven of the 12 games on its schedule because of pandemic concerns. Yet the Owls, 1-2 at the time, pulled a remarkable upset by beating the then-undefeated and nationally ranked Marshall Thundering Herd in a dominating shutout recently.

The 2020 season has become a time to expect the unexpected.

And against a backdrop of sobering statistics related to the pandemic, these games have offered a welcome expression of vitality and exuberance.

Teams that normally schedule opponents years in advance suddenly were looking around from week to week to find a quick game with a team not sidelined by COVID-19 precautions.

In one game Brigham Young University made a quick deal to play Coastal Carolina and in just a few days flew nearly cross-country to play. The two undefeated schools put on quite a show, with Coastal prevailing by a whisker.

A quick glance at the top contenders for the national championship might suggest business as usual: Perennial powers Alabama, Notre Dame, Clemson, and Ohio State top the list. But even these teams have had to endure unusual hardships.

Ohio State recently played Michigan State with its head coach and 23 of its players unavailable – including several starters – mostly due to pandemic-related causes. (It still won 52-12.) Other traditional powers, such as Penn State, Michigan, and Louisiana State University (the defending national champion) have suddenly fallen on hard times, struggling to win a handful of games among them.

On the flip side are the amazing upstarts, who are treating their fans to unexpected successes. Teams like the Iowa State Cyclones and the Indiana Hoosiers have risen from their accustomed place at the bottom of the standings to post sparkling records.

Much of the chaos, of course, can be attributed to the pandemic. Games are canceled or postponed when positive tests pop up on a team. But even before the season more than 150 players had decided to opt out of playing this year. Many more have joined them as the fall has progressed.

Amid all this disruption, bright spots emerged. One has been the fun of watching matchups between teams that have never played each other. One lesson may be to schedule fewer games years in advance and add more spontaneous pairings.

If 2020 is teaching anything in sports, it’s that keeping things flexible isn’t as impossible as previously thought.

Another lesson is that playing through the pandemic – with all due precautions – seems to have brought players and coaches even closer. At Indiana, for example, the upstart team’s slogan is “LEO” – love each other.

The love runs from coach to players too. At Iowa State, head coach Matt Campbell told The Washington Post, “The neat thing about this group of seniors that we have is all 16 have become the best version of themselves they can be.”

That’s one good effect on athletes in any season – not just the surreal one of 2020.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Unwrapping the healing gift of stillness

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Larissa Snorek

Even when circumstances are turbulent or overwhelming, the Christ-spirit is here to wake us up to the peace and harmony God expresses in everyone. And as a woman experienced when recurring pain came to a head one Christmastime, this spiritual stillness opens the door to healing.

Unwrapping the healing gift of stillness

My favorite moments of recent Christmases have occurred in the wee hours of the morning on Christmas Day. In the silent stillness, accompanied only by the twinkling lights from the Christmas tree, it’s easy to feel the power of the Christ-spirit that is at the heart of the sacredness of the season.

But what about at other times, like when we have a huge to-do list, there are too many bills that need paying, we’re in the middle of a contentious family gathering, or we’re dealing with any number of challenges from life during a pandemic?

Even at these moments, Christ, the divine influence in human consciousness, is present to bring the spiritual stillness that rescues us. The Bible articulates this stillness in terms of knowing God. It says in Psalms, “Be still, and know that I am God” (46:10).

So, how do we “know God”? “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, explains that “Spirit, God, is heard when the senses are silent” (p. 89). This occurs as we let the Christ still our mental churning. Then we can find a deep-settled calm and peace, even in the midst of a lot of things going on. The more the human, mortal view of life gets quiet, the more the beauty and joy of life in Spirit, God, is seen.

It’s clear in the New Testament that God and Jesus, Father and Son, were in constant communication, silently. The poise Jesus had came from his awareness of and inseparability from God’s healing presence and power.

Such mental stillness is a natural occurrence for us as children of God. As we cultivate an awareness of God’s divine presence as ever with us, we feel spiritual stillness. Acknowledging God’s goodness and peace working in our lives, we can take action from the standpoint of stillness – rather than feeling pulled by worries or demands.

No matter how turbulent things might be, there is a stillness within that connects us with this divine presence. As we become conscious of God’s allness, we come to understand that the calm we seek isn’t a distant refuge; it is actually the reality of being within – infinite and universal.

All our doing and planning and fixing and solving would have us thinking we need to rely on an ever-active human mind. But, as Mrs. Eddy explained, “The best spiritual type of Christly method for uplifting human thought and imparting divine Truth, is stationary power, stillness, and strength; and when this spiritual ideal is made our own, it becomes the model for human action” (“Retrospection and Introspection,” p. 93).

Stillness as the model for action is a revolutionary idea. And it brings healing. Years ago, just before Christmas, I was struck with such intense pain in my neck and shoulders that I was forced to stop everything and lie completely still. I’d been having bouts of tension and what seemed to be pinched nerves for a number of years, yet this was unlike anything I’d experienced before. In previous times, I’d prayed and found temporary relief. But on this day, I hungered for permanent freedom and deeper peace.

It can take some effort to mentally stand still, to find “stationary power,” when we feel personally in charge of so many things. Yet we are each capable of this, and God as divine Love shepherds us every step of the way. To relinquish perfectionism, control, worry, and concern is to follow this shepherding with grace and humility. Retrospection and Introspection says about God as divine Mind, “Mind demonstrates omnipresence and omnipotence, but Mind revolves on a spiritual axis, and its power is displayed and its presence felt in eternal stillness and immovable Love” (pp. 88-89).

As I accepted this eternal stillness, the intensity of burden and stress melted away. And so did the tightness and pain. That was the last time my neck and shoulders seized up.

As Christ fills consciousness, it leads us into silent conversation with God. The essence of spiritual stillness is felt during this communing, not only in good times but also in harder times. Whenever we honor this spiritual oneness with God, through Christ, as Jesus came to show us, we find ongoing stillness in our hearts. This is the healing gift that is not dependent on outward circumstances, but can be felt within, from one moment to the next.

Adapted from an editorial published in the December 2020 issue of The Christian Science Journal.

Some more great ideas! To read an article on how God’s pure love empowers us to recognize and heal racism titled “Healing ‘humanity’s sore heart,’” please click through to www.JSH-Online.com. There is no paywall for this content.

A message of love

By a nose

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow when we’ll have two stories, from the Middle East and France, that look at efforts to improve human rights.