- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 13 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- The crisis chancellor: How Merkel changed Germany – and the world

- Vaccine mandates: How sincere is a ‘sincerely held belief’?

- A national model? How Virginia is improving landlord-tenant relations.

- The battle to save Earth’s largest tree from California’s wildfires

- Environmental justice at work: From New Jersey water to Indonesian air

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Truth-telling and a path to healing

Until recently, if visitors walked the Walnut Street Bridge in Chattanooga, Tennessee, they likely would be unaware of its troubled history. But yesterday, that changed – in a way many hope will promote reconciliation.

On March 19, 1906, a murderous crowd surged to the bridge, where they lynched Ed Johnson. The young Black man had been accused of raping a white woman and was sentenced to death after a flagrantly biased trial. When he was granted a stay of execution by the U.S. Supreme Court, white residents turned to mob violence.

On Sept. 19, 2021, a very different crowd gathered on the bridge. In a spirit of righting history, the diverse group of hundreds walked across the Tennessee River. Then, amid song and the spoken word, including a formal apology from Mayor Tim Kelly, they witnessed the unveiling of the Ed Johnson Memorial, the result of years of work to bring the case to light and heal a city. Now, the bridge’s full story – of violence and bravery, of inhumanity as well as courage and deep spiritual faith – is there for all to learn from.

The Johnson case left a powerful mark. The appeal to the Supreme Court was one of the first by a Black attorney. The court’s order of a federal review of Johnson’s conviction was unusual for a tribunal that long ignored unconstitutional procedures in the South. After the lynching, the Supreme Court conducted its only criminal trial in history, resulting in several convictions. Justice Thurgood Marshall would later say it was the first time Black people saw the court act on their behalf.

“Remembrance, reconciliation, healing” is the spirit underlying the memorial. Eddie Glaude Jr., professor of African American studies at Princeton University, said Sunday that to create a better America, “we gotta tell the truth.”

That opens the door to progress. As Eric Atkins, vice chairman of the Ed Johnson Project, put it: “When hearts and minds are intermingled, you can achieve things you thought were impossible.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

The crisis chancellor: How Merkel changed Germany – and the world

Angela Merkel, who is stepping down as chancellor, exuded a quiet assuredness and willingness to embrace change that made her a force on the global stage. That legacy, some say, was rooted in her upbringing in East Germany.

Steady and resolute.

Thinking back, that’s how teachers describe the studious pupil from the German Democratic Republic. The description held when, as a middle schooler, she started winning academic Olympiads.

Decades later, those same qualities carried Angela Merkel to the pinnacle of German government, where she led the now-united Federal Republic of Germany for nearly two decades. In an era of disorder and crises, Chancellor Merkel was pragmatic and methodical, a position that won both admirers and detractors.

“You either admire the stability over her 16 years or criticize her lack of vision,” says Martin Gross, a political scientist.

In 2015 came the decision that’s sure to be the most indelible part of her legacy. Ms. Merkel opened Germany’s doors to an influx of more than a million refugees, mostly from Syria and Afghanistan. The decision might have helped enable the rise of Germany’s far-right. At the same time, supporters argue anti-immigrant populism was a global phenomenon.

Some domestic priorities – like education and infrastructure – seem to have been left behind, critics note. History may judge Ms. Merkel more harshly than the mostly complimentary assessments she gets today. Or maybe not: As one veteran German political reporter predicts, “the nostalgia for her will start within two years after her leaving office.”

The crisis chancellor: How Merkel changed Germany – and the world

The road between the German autobahn and Chancellor Angela Merkel’s tiny hometown is flanked with a canopy of trees. They crowd the narrow winding asphalt, genuflecting to the wind, as you cast off the speed and modernity that is Berlin and approach the historic, cobblestoned town of Templin.

Only 17,000 people reside here, yet Templin is the seventh largest town in Germany by area, because its borders include the surrounding Uckermark forest. This is the former German Democratic Republic (GDR), the communist state where Ms. Merkel was raised.

Decades after the fall of East Germany, high unemployment still grips a region that is anchored by farming on top of whatever tourism dollars come its way. Ironically, the place that gifted Germany its first female chancellor is also a stronghold for the country’s far-right political party. Still, Ms. Merkel is drawn to the forest, and her pastor father and English-teacher mother lived here up until their deaths. Ms. Merkel will likely return often after she closes out 16 years of service as chancellor. She has a longtime country home here, and it’s styled as modestly as she is.

“Merkel doesn’t have a Camp David,” says Detlef Tabbert, Templin’s mayor and a contemporary of Ms. Merkel’s who attended the same high school. “She’s often here. She often drives herself. She does her own grocery shopping.”

As he reflected upon her career, Mr. Tabbert remarked that her 36 years in East Germany “allowed her to make great decisions” during the many crises she faced as chancellor. “Daily life for Merkel here when she was young had many challenges,” he says.

Indeed, some Merkel watchers say the key to her legacy – most often identified as her stellar crisis management skills and a humble-but-resolute leadership style – can be found in her upbringing as a child of the GDR. Her chancellorship was characterized by trial after tribulation that earned her the nickname “The Crisis Chancellor.” There was the global recession and eurozone crisis, followed by her singular determination to phase out nuclear energy in Germany after the Fukushima disaster in Japan. A controversial decision to ultimately allow a million migrants into Germany from Syria and Afghanistan is sometimes credited with enabling the rise of the far-right, then the pandemic gave Ms. Merkel a chance to showcase her steady scientific hand.

Critics say she wasn’t tough enough on Eastern Europe’s dictators, nor did she corral Russian President Vladimir Putin, a man who speaks her native language just as fluently as she speaks his. Yet overall, she leaves Germany better than she found it, stronger economically, more socially diverse, and the undisputed heart of the European Union. Ms. Merkel’s most impactful decisions were made over the objections of her own party, yet she still managed to stay in power, which speaks to her stamina and political skill.

Unlike her predecessors, either dogged by the whiff of impropriety or voted out of office, Ms. Merkel was scandal-free and served for “a very long time in government,” says Marianne Kneuer, professor of comparative politics at the University of Hildesheim. “That made her a long-term player in international politics, a constant actor who always had more experience than the others.”

“You either admire the stability over her 16 years or criticize her lack of vision,” says Martin Gross, assistant professor of political science at Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich. “Globally she’s helped preserve the liberal world order in a time of chaos. But what’s the vision for Germany for 2050? She doesn’t have one. Her style – this incremental policy style – has to do in part with her raising in the GDR. She has a backup to the backup to the backup option, and she’s allergic to huge visions about society because she lived in one that failed.”

As a child, Angela Kasner was quiet and studious, according to her grade school teachers.

She was born in Hamburg in 1954 to a Lutheran pastor father, who made the unusual decision to move his young family from the West to the East at a time when East Germans clamored to go the other way. The Kasners relocated to Templin when Angela was an infant. She was raised in comfortable surroundings as the daughter of a man with power in the community. She never called attention to herself. Angela wore her hair in a nondescript football-helmet style, and she was always “lost in her own world” of studies, as one teacher put it.

Even though from a notable family, she would mix freely with the children of clothing factory workers. “The head hospital doctor had 60% more income than the bus driver, not 10 times as much,” recalls Mayor Tabbert. “The differences between all of us were very marginal, and we were all together for a long time. This shaped our empathy and our social conscience.”

One difference soon became impossible to ignore: Angela’s work ethic and intellect.

“A colleague alerted me to a seventh grade student who was really good,” says Erika Benn, who taught Russian in Templin and still lives there today. That student was a preteen Angela, who began going to Ms. Benn’s home several hours a week for extra Russian lessons.

Before long, Angela was winning district, regional, and finally national GDR language Olympiads, which were a way to identify young talent in the East bloc. Angela’s wins brought fame to Ms. Benn, who says her student was nearly perfect, except that she had to teach her “how to look in people’s eyes. She was shy; she held back.”

“From the beginning, she was the best,” says Ms. Benn. “The other students weren’t even jealous because they knew they could never be as good. She was very disciplined at a very young age, and she wanted to win.”

“There were a few boys with those math skills but never a girl,” says middle school math teacher Hans-Ulrich Beeskow. (Angela began winning math Olympiads, too.) “The level of math was very difficult, and students needed extra time. Angela Kasner never needed that extra time.”

Later, as the teachers watched their star pupil climb the ladder of German democracy, they made a parlor game out of discerning hints of her upbringing. Mr. Beeskow likes to say her political acuity stems from her mathematical background.

“She never made decisions on her own – she always relied on experts,” says Mr. Beeskow. “She relied on [virologist] Christian Drosten during corona, for example. She hears the arguments of others, and this has something to do with math. Because logical thinking is the No. 1 priority.”

Ms. Benn, meanwhile, scoured Ms. Merkel’s speeches and policy moves for connections to the East. She found little. “I was angry at her for awhile, but I do think she passed the single-mother-retirement package [of legislation] for mothers in the East. The mothers in the West didn’t need it – they had enough money.”

Just down the road in Templin, inside the formidable structure that housed Ms. Merkel’s high school, the schoolchildren have no anger or resentment toward the chancellor and her allegiances, apparent or not, to her past. They’ve only known a unified Germany, and they think it’s “super cool” that Ms. Merkel went there, says Kerstin Alexandrin, a math teacher at Templin’s Active Nature School.

“The children say, ‘It’s possible to become chancellor if you go to school here.’”

Ms. Merkel’s rise through the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) – the political party that has been her home for 30 years – was swift.

When Germany reunified in 1990, she’d been working as a research scientist after earning her Ph.D. in quantum chemistry. The night the Berlin Wall fell, she famously went to her weekly sauna appointment with a friend and headed off to work the next day. Regardless, she quickly became swept up in the developing democratic movement. She was soon elected to the Bundestag to represent the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern.

Chancellor Helmut Kohl almost immediately appointed her minister for women and youth, and Ms. Merkel also served as environment minister before ascending to CDU leadership in the late 1990s. Finally, in 2005, in what would be the closest election of her political career, she rose to the chancellorship after months of coalition negotiations.

From the start, Ms. Merkel revealed herself as someone who meticulously “surveyed the landscape for signals and made risk assessments,” says Stefan Reinecke, longtime parliament correspondent for the Taz newspaper. “She didn’t invent it, but she perfected the German superpragmatism that meant there was never serious political discourse. Only the middle.”

Her negotiation tactics and ability to compromise would serve her well, as one crisis after another emerged. She would outlast anyone in the negotiating room, says Andrea Römmele, a political consultant and professor at the Hertie School, a graduate school in Berlin. “The picture that remains in my head is that she’s the last one standing, when all the other heads of state were ready to go back to their hotel rooms. She had stamina.”

During the global financial recession of 2008-09, followed by the eurozone crisis, Ms. Merkel signaled that domestic interests were top priority in a “hard-nosed, very nationalistic way of pushing German interests in the EU,” says Mr. Reinecke. She supported a multibillion-dollar bailout of a German financial institution, but later opposed extending similar debt forgiveness to Greece and other Southern European countries that were headed toward insolvency.

She stoked stereotypes of lazy Greeks in comments about abundant vacation days and a retirement age that was lower than Germany’s, remarks almost certainly directed toward her domestic audience. Regardless, she ultimately helped negotiate a bailout for Greece. “If the euro fails, then Europe fails. Europe wins when the euro wins,” Ms. Merkel said ahead of a second vote on a proposed financial package.

“She held the place together,” says Dominik Geppert, professor of history at the University of Potsdam in Germany. “She wanted to make sure that the EU didn’t fall apart in the most difficult phases: the debt-crisis with Greece, Brexit, and [the coronavirus]. With diplomatic skill and the ability to strike a balance, she succeeded in doing so.”

Steady and resolute as she was, she could easily about-face, as she did with her 2011 decision to phase out nuclear energy. Just the previous year, she supported extending the working lives of Germany’s 17 nuclear power plants, but the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan flipped her outlook. “The dramatic events in Japan are a watershed moment for the world, a watershed for me personally,” Ms. Merkel said. Prior to Fukushima, “I accepted the residual risk of nuclear energy.”

The 2011 Bundestag vote to eliminate nuclear power in Germany within about a decade had staggering consequences. It dramatically boosted the renewable energy industry but also made Germany more reliant on coal and on imported sources of energy, such as natural gas.

Still, the decision to wean Germany off the atom was “epoch-making,” says Michael Borchard, head of the Archive for Christian-Democratic Policy at the Konrad-Adenauer Foundation. “The nuclear phaseout didn’t just mean the end of this technology, but it was also a huge turnaround for Germany. This switch to renewable energy was way before its time, faster than in any other industrialized nation, even if it’s still an unfinished project.”

In 2015 came the decision that’s sure to be the most indelible part of her legacy. Ms. Merkel opened Germany’s doors to an influx of more than a million refugees, mostly from Syria and Afghanistan. “Germany is a strong country. ... We have accomplished so much – we can do it!” she said, trumpeting a phrase that would be famously repeated.

This was an abrupt departure from the CDU’s longtime position on migration. “Germany is not an immigration country,” proclaimed Helmut Kohl in the 1990s when he was head of the party. Even though the country had allowed in “guest workers” for years, Mr. Kohl’s remarks reflected the CDU’s prevailing social conservatism on immigration issues. With her single stroke in 2015, Ms. Merkel shifted her party to the left on migration.

“This has been a repeating pattern with her, to make ‘Merkel decisions’ that did not actually correspond to the CDU’s value system,” says Ursula Münch, a political scientist and current director of the independent think tank Academy for Political Education in Bavaria. “That was accepted because she managed to win elections for the party. The woman had almost an impeccable sense for where voters are to be found across a broad spectrum.”

Her upbringing in a pastor’s home likely influenced the migration decision, experts say. Five years on, statistics show about half the new arrivals have found housing and work, with their children enrolled in German public schools. The decision might have helped enable the rise of Germany’s far-right, but supporters note populism was a global phenomenon.

Throughout crisis after crisis – whether it was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the rise of Donald Trump and his mercurial policies, or climate change disasters such as 2021’s floods – Ms. Merkel held her hand steady. Many have criticized her for lacking strategic vision, but she was typically good when a situation called for calm control.

A childhood in the GDR surely required practicing control, and it also nurtured a tendency to keep a tight lid on grand visions. Ms. Merkel has shown both characteristics throughout her chancellorship.

“It wasn’t as if the secret service was everywhere, but you can’t deny it was a surveillance state,” says Mayor Tabbert of his and Ms. Merkel’s childhood in Templin. Planning for a party required alternative options in case the first choice was forbidden or unavailable. A child of the GDR also grew up thinking about boundaries.

During her last year of high school, Merkel and her classmates presented an anti-state poem that mentioned a “wall,” according to Mr. Beeskow, the math teacher. The students were nearly kicked out of school. “She grew up learning where the line was,” he says. “She could push but she knew where to stop.”

Perhaps as chancellor, she didn’t push enough boundaries, say critics. Take European integration. Anything she did there was reactive, says Dr. Geppert, the historian. “The stronger European integration [that resulted] was a byproduct of the debt and euro crisis. Not so much by choice, but by events.”

Even her actions on refugees might have been prompted by an unwillingness to see German police officers usher women and children back across the Austrian border, remarks Mr. Reinecke, the parliamentary journalist. “Did she want that? No. Perhaps her origins in a pastor household did come into play. But her essence, her political essence, was not to have [an essence] at all.”

Ms. Merkel did leave plenty unfinished when it comes to domestic priorities. Germany failed to modernize a digital infrastructure that’s among the oldest and slowest in Western Europe, and the quality of education hasn’t markedly improved. (An Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development survey recently found Germany ranks 29th out of 34 industrialized economies for internet speeds.) She has left a “massive investment backlog in digitization, education, and a public transportation infrastructure that makes you long for more,” says Mr. Reinecke. “And that’s in one of the richest countries in the world.”

Ms. Merkel also failed to smooth the way for a successor. She abandoned several potential picks despite their loyalty to her, or because of missteps they made. “The reporting hasn’t been critical enough on this part,” says Dr. Geppert.

History may judge Ms. Merkel more harshly than the mostly complimentary assessments she gets today. Her success might have simply been “good timing,” says Dr. Geppert. “It’s a bit like Tony Blair [of Britain].” She benefited from an economic boom, spurred in part by Agenda 2010 – reforms instituted by a Social Democratic-Green coalition. “She didn’t actually secure and advance that [agenda], but rather raked in the dividends,” he says. “If you look back, what has actually been achieved?”

One thing is certain: the global coronavirus crisis allows Ms. Merkel to leave on a high note. Early on in the pandemic, she overcame her typical reticence, detailing the challenges ahead and summoning Germans to do their duty to society. It was a stark contrast to the approach taken by President Trump, and her popularity soared. She reached “70 to 80% approval, which was incredibly high compared with the migration crisis,” says Dr. Kneuer,the comparative politics expert. “People during corona felt very comfortable with her. They said, ‘We do not want another leader other than her.’”

It was a remarkable capstone to a long political career, especially as “she’s been losing voters for years,” says political consultant Gertrud Höhler. “This wasn’t really noticed, because you share the spectrum with six or seven other parties and the one with 24% can govern.”

Ultimately, says Dr. Kneuer, “if she’ll be identified as one of the great world leaders, it will be because others judge her accomplishments that way and certainly not because she wanted to, because she is free of peacocking vanity.”

While Ms. Merkel might be leaving some Germans wanting more – “the nostalgia for her will start within two years after her leaving office,” predicts Mr. Reinecke – the departing chancellor herself is envisioning quiet solitude. When recently asked about her plans, she said she won’t miss having to make decisions all the time. She also thinks about “someone else doing it now. And I think I’d like that very much.”

Back in forested Templin on a sunny afternoon, a stop at the tourist bureau reveals four women wholly unimpressed that their town gave the world Angela Merkel.

“It’s East Germany. No one cares if someone’s a celebrity or famous person,” says Karin Buse, who’s worked at the tourist bureau for 16 years, a stretch as long as Ms. Merkel’s been chancellor. “No one asks whether [she] is from here.”

“They come for the hot spring baths and relaxation.”

Vaccine mandates: How sincere is a ‘sincerely held belief’?

Virtually no religious denominations officially object to the COVID-19 vaccines. But more people are seeking faith-based exemptions. Employers now must decide how – and whether – to weigh the merits of their case.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

While large businesses generally favor President Joe Biden’s vaccine mandates as offering clarity, they now find themselves in the position of having to decide what “sincerely religious” means as the number of requests for exemptions based on faith rise.

As the delta variant created a surge in caseload this summer, overwhelming a number of hospitals in states with lower rates of vaccination, many employers have felt caught between two legally fraught obligations: providing a safe workplace while at the same time evaluating employees’ requests to opt out of getting a vaccine for religious reasons.

Officially, most religious groups have supported vaccines, and the pope and a number of prominent Evangelicals have urged their followers to get the vaccine. But America’s civil rights traditions specifically focus on the religious beliefs of an individual.

For businesses, questioning the sincerity of an employee’s religious belief is both legally and practically fraught, employment experts say.

“This is an area where the distinction between a religious and ethical objection and a political and policy objection will get really fuzzy really quickly, and that’s going to put employers in a very difficult position,” says Jamie Prenkert, professor of business law at Indiana University’s Kelley School of Business.

Vaccine mandates: How sincere is a ‘sincerely held belief’?

Over the past year, a significant number of American workers on both the right and left have expressed political objections to getting a vaccine.

Many have appealed to ideas of individual freedom, personal choice, and the integrity of their bodies, or concerns over the safety of the COVID-19 vaccines that were developed and tested in a relatively short amount of time.

But as new state and federal mandates begin to require vaccination as a necessary condition for workplace safety, many U.S. employers have been receiving a growing number of requests from employees seeking exemptions based on their religious objections.

Such requests have a long and sometimes contentious history in American workplaces. Yet the country’s robust civil rights traditions have generally given workers with “sincerely held religious beliefs” a lot of leeway, so long as the accommodations they seek to exercise their faith freely do not cost employers more than a minimal expense.

As the delta variant created a surge in caseload this summer, overwhelming a number of hospitals in states with lower rates of vaccination, many employers have felt caught between two legally fraught obligations: providing a safe workplace while at the same time evaluating employees’ requests to opt out of getting a vaccine for religious reasons.

“This is an area where the distinction between a religious and ethical objection and a political and policy objection will get really fuzzy really quickly, and that’s going to put employers in a very difficult position,” says Jamie Prenkert, professor of business law at Indiana University’s Kelley School of Business in Bloomington.

“The courts have been pretty clear that the religious exemption process can apply to non-theistic ethical or moral objections, but not to policy or political objections,” Professor Prenkert says. “But depending on how people voice those objections, that becomes a very difficult line to draw.”

For most of this year, most businesses have hesitated to mandate vaccines. Facing worker shortages and a maelstrom of political controversies during the shutdown, some opted instead for a “carrot” approach, encouraging their employees to get inoculated by offering in some cases up to $500 in bonuses or extra hours of pay.

But even before President Joe Biden announced his controversial plan to institute a sweeping vaccine mandate affecting some 100 million American workers, many employers began to take a harder line, putting in place their own mandates as cases began to surge.

In an August poll of nearly 1,000 U.S. businesses employing some 10 million workers, the consultant Willis Towers Watson found that over half of those surveyed said they would put in place some sort of vaccine mandate over the next few months – more than doubling the 21% of businesses that were already mandating vaccines.

“These new federal requirements will now give employers some cover,” says Sharona Hoffman, a professor of law and bioethics at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio. “They won’t have to come up with some independent policy that they have to figure out and then struggle to put in place.”

Religious exemption requests on rise

At the same time, however, many employers, both private and public, have struggled with the number of religious exemptions they are starting to receive as more employees begin to explore how to apply.

“This topic is challenging for the individuals charged with sorting through and approving or denying the religious exemption requests,” says Richard Tarpey, assistant professor of management at Middle Tennessee State University’s Jones College of Business. “It seems apparent that some workers who have not held a religious belief against a vaccine in the past now may claim to hold one.”

A number of evangelical pastors and Republican lawmakers have urged their followers to claim a religious exemption in response to vaccine mandates in the workplace, some offering to write letters to employers to support their religious claims. Conservative legal groups have already filed legal challenges to those denying such requests.

Last month, when New York health officials approved a sweeping new vaccine mandate covering most of the state’s health care workers, it also decided to eliminate religious exemptions. Even though such exemptions had been included in the state’s previous emergency orders, observers say officials were becoming concerned over the significant rise in the number of health care employees submitting applications to opt out of the state’s vaccine mandates for religious reasons.

A federal judge blocked New York’s mandate this month, however, after a number of doctors, nurses, and other health care workers, each of whom wished to remain anonymous, sued the state for violating state and federal protections against religious discrimination.

The plaintiffs are “imminently at risk of professional destruction, loss of livelihood and reduction to second-class citizenship because they cannot in conscience, given their sincere religious beliefs, consent to be injected with vaccines that were tested, developed or produced with cell lines” from fetuses, wrote The Thomas More Society, which helped the plaintiffs bring their case, in a memorandum to the court.

Religious opponents to vaccine mandates have begun to coalesce around the politically contentious issue of abortion when explaining their reasons for seeking exemptions, observers say.

For businesses, questioning the sincerity of an employee’s religious belief is both legally and practically fraught, employment experts say.

“Generally speaking, when it comes to religious accommodations, employers do need to take employees at their word,” says Erika Todd, an employment attorney at Sullivan & Worcester in Boston. “There can be some amount of room to ask some follow up questions, and there might be an issue if an employer does have a specific reason to question whether a particular employee’s objection is based on a sincere religious belief or a political belief.”

Officially, most religious groups have supported vaccines, and a number of prominent Evangelicals and outspoken opponents of abortion have urged their followers to get the vaccine. “I will take it not only for what I hope will be the good of my own health, but for others as well,” wrote Al Mohler, president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, on his website.

Pope Francis has called getting a vaccine “a simple but profound way of promoting the common good and caring for each other, especially the most vulnerable,” and the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has proclaimed that getting vaccinated “ought to be understood as an act of charity toward the other members of our community.”

In a public statement on the issue, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, the publisher of the Monitor, said: “For more than a century, our denomination has counseled respect for public health authorities and conscientious obedience to the laws of the land, including those requiring vaccination. ... We see this as a matter of basic Golden Rule ethics and New Testament love.”

Beliefs of an individual, not a denomination

But America’s civil rights traditions specifically focus on the religious beliefs of an individual. Although some leaders have been offering to supply employees with a religious version of a “doctor’s note,” these are not necessary, Ms. Todd says.

Indeed, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission makes that clear. “An employee’s belief or practice can be ‘religious’ ... even if the employee is affiliated with a religious group that does not espouse or recognize that individual’s belief or practice, or if few – or no – other people adhere to it, explains the EEOC.

But employers may still ask employees to explain their religious beliefs in writing, says Bob Nichols, co-head of the labor & employment practice in the Houston office of Bracewell LLP.

“You could ask them to write you an attestation or an explanation that they have this sincerely held religious belief – and that’s what our clients can and routinely do, and I think it’s appropriate,” says Mr. Nichols, who has been advising Fortune 500 companies throughout the pandemic. “They can say, ‘OK, write me a statement attesting to that belief or practice you say you have, and to the best you can, please explain that belief to me and sign it.’”

Some employers had begun to take a harder line with their employees, even before the Biden administration’s mandate.

Earlier this month, United Airlines told employees that those receiving religious exemptions from the company’s mandate would be placed on unpaid personal leave starting on Oct. 2. Those employees would be allowed to come back to work, the company said, after it figured out how to put into place appropriate testing and safety measures.

Employers are starting to consider health coverage surcharges for those employees who refuse to be vaccinated, even if for religious reasons, a tactic more firms are starting to review as one alternative to a mandate, writes Wade Symons, an employment benefits attorney with the human resources firm Mercer.

Last month, Delta Airlines was among the first to announce it would be adding a $200-a-month health insurance surcharge for employees who refused to get a vaccine.

Some companies, too, have been aggressive in testing the sincerity of their employees’ religious beliefs. Conway Regional Health System, a health care provider in Arkansas, asked employees seeking an exemption to sign a “Religious Exemption Attestation for COVID-19 Vaccine.”

Since the majority of Conway’s requests cited religious opposition to the use of fetal cell lines, the form listed dozens of common pharmaceutical products that also used fetal cells in their development, including products such as ibuprofen, Tylenol, Pepto-Bismol, and Tums.

“I truthfully acknowledge and affirm that my sincerely held religious belief is consistent and true and I do not use or will use any of the medications listed …” the attestation form states.

“We thought it was prudent just to try to get some clarification with staff, so the staff understood what they were committing to,” Conway’s CEO Matt Troup told KATV in Little Rock. “This isn’t an attempt to try to shame people in any way. It is to make sure that they understand just how ubiquitous these fetal cell lines are.”

While such tactics might exacerbate workplace tensions, Professor Tarpey at Middle Tennessee State University says “employees who have a sincere religious belief against a vaccine should be able to articulate the belief and how getting the vaccine will specifically violate the belief offered.”

“Ultimately, these issues will most likely end up in the courts, considering the polarized nature of the various state laws that exist ... and the forthcoming [Biden administration] vaccine requirement,” he says. “Employers will need to balance the many needs of the organization, especially during tight labor market times. Customer and co-worker protection will need to be balanced against having enough staff to run the organization should vaccine resistance on a religious basis become widespread at a company.”

A national model? How Virginia is improving landlord-tenant relations.

Is it really possible to reset the relationship between tenants and landlords? Virginia’s progress on long-standing housing issues might serve as a model for the nation.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Three years after Virginia made national news for having one of the highest eviction rates in the country, the state has responded with an array of new protections for tenants. And to date, Virginia has distributed the nation’s highest share of pandemic rent relief money allocated by Congress.

With proper checks and balances, eviction is an important shield, protecting landlords from careless tenants. But that shield can too easily become a sword, says Alieza Durana from Princeton’s Eviction Lab. The challenge for lawmakers is writing policy that protects both parties, she adds.

Rent relief can play a part in that.

For Cedric Simmons, who received an eviction notice last month, Virginia’s rent relief program was a game changer. A gig worker with child care costs and car repair bills, he’d fallen behind on his rent. But he qualified for state aid that allowed him to stay in his home.

Now, he’s studying for an exam that could help him land a more stable job in information technology, and he’s saving money.

“Those people [who helped me apply for rent relief] are my angels,” says Mr. Simmons. “They will never be forgotten for the rest of my life.”

A national model? How Virginia is improving landlord-tenant relations.

On Aug. 20, Cedric Simmons heard a knock on his apartment door south of the James River in Richmond, Virginia. A police officer served him a notice from his landlord: Mr. Simmons had until Sept. 9 to leave the apartment.

He was being evicted.

At that point Mr. Simmons owed almost $4,600 in back rent – the result of inconsistent income from gig work, day care costs for his daughter, and car repairs he needed this summer. Despite 16-hour workdays and trying to save up, he says, “it just kept spiraling out of control.”

But on his notice there was a phone number to call for assistance. The people he spoke with referred him to the state’s rent relief program, and about a week later he heard back. A representative asked for documents and a trip to the courthouse, and in about five days, he received word that the state would cover his back rent. Mr. Simmons still had a home.

“If they didn’t step into place … I would probably be homeless,” he says.

Three years after Virginia made national news for having one of the highest eviction rates in the country, the state has responded with an array of new protections for tenants like Mr. Simmons. The General Assembly has passed nearly two dozen bills – many with bipartisan support – resetting the relationship between tenants and landlords. To date, Virginia has distributed the nation’s highest share of pandemic rent relief money allocated by Congress.

“The two are just inextricably linked: The success of Virginia in getting out rent relief money is a direct result of national exposure of Virginia having so many cities with a high eviction rate,” says Marty Wegbreit, director of litigation at the Central Virginia Legal Aid Society.

With the Supreme Court’s rejection of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest eviction moratorium, which could contribute to a potential 750,000 evictions by the end of the year, such aid and advocacy is as important as ever. Once a cause of shame for being insufficient, Virginia’s tenant protections have become a role model. Other states may benefit from following its example.

“We’d like to see them do that,” says Mr. Wegbreit.

Embarrassment leads to progress

Just three years ago, Mr. Wegbreit was fretting over research that showed a very different picture of Virginia’s housing landscape.

Princeton University’s Eviction Lab had released a ranking of the country’s top evicting cities. Of those, Virginia had three of the top five and five of the top 10. Richmond, the capital, had the second-highest eviction rate in the country.

Virginia made “the national news in a way that no state and no city ever wants to,” says Mr. Wegbreit.

With proper checks and balances, eviction is an important shield, protecting landlords from careless tenants. But that shield can too easily become a sword, says Alieza Durana, narrative change liaison for Princeton’s Eviction Lab. Landlords can use the threat of eviction to coerce tenants – often unaware of their legal rights – into paying rent immediately or ignoring problems in their apartments. There’s already a national shortage of affordable housing for low-income renters. If evicted, tenants can fall into a cycle of poverty and homelessness.

The challenge for lawmakers, says Ms. Durana, is writing policy that protects both parties. That task is even more difficult in a rental landscape that spans “mom and pop” landlords trying to pay down mortgages on the one hand and profit-hungry serial evictors on the other, who target the same tenant for eviction repeatedly. Eviction should be “a tool of last resort,” says Ms. Durana, but in many places it is wielded as “a rent collection tool.”

The Eviction Lab’s 2018 report showed how much eviction was being misused in Virginia and signaled a power imbalance between the state’s renters and landlords, says Mr. Wegbreit. Immediately, he says, “a lot of attention got focused on trying to improve the situation for Virginia tenants.”

During the following fall and spring a Republican-controlled General Assembly passed seven or so tenant-friendly laws signed by Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam. That trend continued in late 2019, when Democrats took over both houses of the state legislature. The reforms afforded tenants more time to pay down back rent, gave them more power to obtain timely repairs in their apartment, and prevented landlords from charging egregious late fees.

An instructive coincidence

Virginia was still remedying its eviction problems when the pandemic began in March of last year. That helped the state connect the two crises, and gave its prevention efforts a kind of kinetic energy. In the year and a half since, Virginia’s eviction policies have been proactive, says Benjamin Teresa, co-director of the RVA Eviction Lab at Virginia Commonwealth University’s L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs.

Perhaps most important, the state was one of the nation’s first to launch a rent relief program last summer. At first only distributing state funds, the program had almost half a year to troubleshoot the process before Congress allocated billions of dollars in rental assistance in January. By then, says Mr. Wegbreit, the state had learned how to disburse funds efficiently.

To date, Virginia has distributed the highest percentage of rent relief funds in the country and the second highest total, next to Texas, says Mr. Wegbreit. Last month Governor Northam restarted the state’s eviction moratorium, which requires landlords to apply for rent relief before they can evict a tenant for nonpayment. The moratorium lasts until next June.

The state government has also passed laws requiring landlords to give 14 days of nonpayment notice, up from five, before filing an eviction case, and banning discrimination based on source of funds – meaning landlords can’t deny tenants because they’re receiving rental assistance.

RVA Eviction Lab’s research shows that eviction filings fell to 19% of pre-pandemic levels during the second quarter of this year.

“Virginia is ahead of the curve when it comes to ... the rent relief program,” says Laura Dobbs, a housing attorney at the Virginia Poverty Law Center. But “that’s only such a small slice” of the eviction landscape.

When tenants need assistance to pay rent, landlords can still choose not to renew their lease – bypassing the legal eviction process but still contributing to housing instability. Tenants also often struggle to corral the necessary paperwork to apply for rent relief or aren’t aware of their rights in the first place.

Even if they are informed, tenants may accept poor treatment if the alternative is homelessness, says Omari al-Qaddafi, a community organizer and housing advocate at Richmond’s Legal Aid Justice Center.

“The landlord has the key,” says Mr. Qaddafi. “He or she is standing in between you and your family being out on the street.”

“Those people are my angels”

The rent relief program helps avoid such a zero-sum game.

Renee Pulliam works as director of operations for residential property services at Cushman and Wakefield, Thalhimer, which leases around 10,000 apartments in Virginia, she says. Of those, around 1,500 have received rental assistance.

The first applications came last August, when the program was still in its infancy. It’s become more streamlined since then, says Ms. Pulliam, and applying for rental assistance is now a normal part of her company’s process.

“If there is rental assistance available and our residents have been impacted and they qualify for the assistance, we are absolutely going to help them secure the funds,” she says.

For Mr. Simmons, who spoke with the Monitor Sept. 9, the day he was scheduled to be evicted, those funds have brought unspeakable relief.

He’s studying for an exam that could help him land a more stable job in information technology by the end of the year, and he’s saving money.

“I’m able to see myself in a completely different place by January,” he says.

After months of anxiety about paying his bills, feeling with every hour worked that he would still fall short, and having it all erased in two weeks, he operates with a new sense of thanks.

“Those people [who helped me apply for rent relief] are my angels, in my eyes,” says Mr. Simmons. “They will never be forgotten for the rest of my life.”

Essay

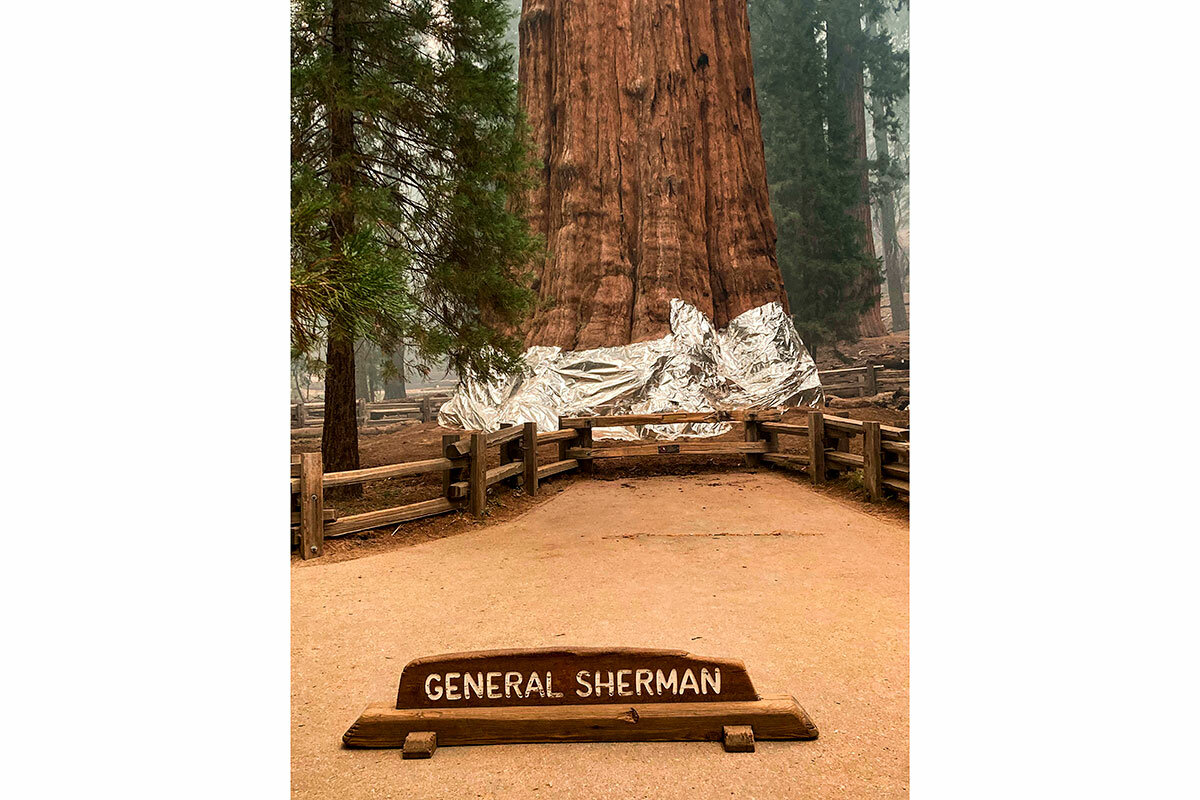

The battle to save Earth’s largest tree from California’s wildfires

Firefighters have battled tirelessly to save one of California’s sequoia groves and its famous General Sherman tree. These efforts underscore the trees’ magnificence – and a resilience challenged by changing climate conditions.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Like so many others, I was concerned when I learned that the KNP Complex fire in California’s Sierra Nevada was dangerously close to the Giant Forest in Sequoia National Park. That’s where the famous – and ginormous – General Sherman tree has stood for thousands of years.

Then I began learning about what all the firefighters are doing to save the sequoias, and my initial “Oh no!” turned into an “Oh my!” Crews have raked the forest floor, burned duff from around the base of individual trees, and wrapped the General Sherman and other named trees in foil reaching 10 to 15 feet high. It’s the same material that firefighters carry to protect themselves in case of a burn-over.

Sequoias are used to fire, said Jon Wallace, the fire’s operation section chief, at a briefing Friday evening. But “we’re taking extra steps to really try to protect those trees,” he added. That’s especially true of the General Sherman. At 275 feet high and more than 36 feet in diameter at the base, it’s the largest tree by volume on the planet.

“We’ll save the Sherman before anything else,” fire information officer Mark Garrett says. For now, it seems, they have.

The battle to save Earth’s largest tree from California’s wildfires

My heart skipped a beat when I read last week that the KNP Complex fire in California’s Sierra Nevada was within a mile of the Giant Forest in Sequoia National Park; just a mile from the park’s main attraction: ginormous, ancient sequoias that include the biggest tree on Earth – the General Sherman.

Oh no! Like millions of people from around the world, I have enjoyed this spectacular park. Not as heavily visited as its majestic, granite cousin Yosemite to the north, Sequoia is all about the trees: craning your neck to see blue sky past evergreens as tall as skyscrapers, walking paths among old-growth behemoths that go back to biblical times, spreading your arms across a tree trunk that’s impossible to hug for its tremendous girth.

But I should have known that firefighters would do everything they could to save this world-renowned forest of nearly 2,000 giant sequoias – trees found only in California. This fire has been designated one of the highest priority fires in the United States. To prepare the Giant Forest, crews have raked the forest floor, burned debris from around the base of individual trees, and wrapped the General Sherman and other named trees in foil reaching 10 to 15 feet high. It’s the same material that firefighters carry to protect themselves in case of a burn-over.

Roads and parking lots provide firefighters access to lay their hoses and run sprinklers pretty much nonstop around the structures in the Giant Forest, and around key lodging and visitor areas elsewhere in the park.

Sequoias are used to fire, said Jon Wallace, the fire’s operation section chief, at a community briefing in the nearby community of Three Rivers Friday evening. But at this level of dryness, “we’re taking extra steps to really try to protect those trees.”

These giants have seen hundreds of fires over their lifetimes of 2,000 to 3,000 years. Thick bark protects them from flames, and the heat from fires forces cones to release their seeds. Branches starting 100 feet up protect the trees’ crowns from flames on the ground. Unusually, the park has a long history of low-intensity prescribed burns dating back to the late 1960s. Over the weekend, the KNP Complex fire had reached the western edge of the Giant Forest, but as Mr. Wallace noted, because of the park’s “impressive” practice of prescribed burns, “there’s not a lot to burn” in the area, and flames have dropped down to 2 to 3 feet.

As of Monday morning, fire had touched only a few sequoias in that western edge – the Four Guardsman – but no giants have been damaged or killed, according to Mark Garrett, a spokesman for the KNP Complex fire. Firefighters have been able to “corral” the low-intensity fire in that area, he said.

Sparked by lightning on Sept. 9, the KNP Complex fire is still 0% contained under red-flag conditions, consuming at least 23,700 acres so far, much of it in unreachable, rugged terrain. But in the much-visited Giant Forest, which sits on a kind of plateau with walking trails, protection efforts are going “really, really well,” said Mr. Wallace at a briefing Sunday morning.

Things did not go well with the Castle fire last year that killed 10% to 14% of the world’s large sequoia population in California’s Sierra Nevada – about 7,500 to 10,600 trees, according to the National Park Service. A history of fire suppression combined with hotter droughts driven by climate change are causing higher flames and hotter fires, say park officials. So far this year, wildfires have burned more than 2 million acres in California, closing Lassen Volcanic National Park in the northern part of the state, Sequoia, and much of neighboring Kings Canyon National Park.

“Yes, fires are beneficial in many cases, but I think what we’re seeing now is a severity and intensity, and too many of them, and that is not really good for the ecology of many of these parks,” says Ana Beatriz Cholo, a spokeswoman for the National Park Service.

Ms. Cholo was recently at Lassen, which is still closed due to the Dixie fire, California’s second-largest fire in history, burning nearly a million acres. Firefighters have been able to save a number of structures and “special spots” for visitors, she says.

And so it is with the General Sherman tree – 275 feet high and more than 36 feet in diameter at the base. That makes it the largest tree by volume on the planet. “We’ll save the Sherman before anything else,” says Mr. Garrett. The General Sherman so far hasn’t even seen fire, he says, because it’s on the northern side of the Giant Forest, and is buffered by a parking lot, a road, and the prescribed burning.

In a few months, even intensely burned areas in the park will see “green stuff sprouting all over,” including ferns, grasses, and shrubs, says Mr. Garrett. Up in the Giant Forest, there will potentially be seedlings, helped by minerals and more sunlight. “Once the fire moves through there, we can see a healthier forest.”

This caused my “Oh no!” to turn into “Oh my!” – at the wonder of the tremendous effort to protect this grove for future visitors, and at these towering sentinels of the forest themselves. It looks like the resilience of these sequoias, aided by people working to save them, will preserve these magnificent trees for future generations of awe-inspired visitors.

Points of Progress

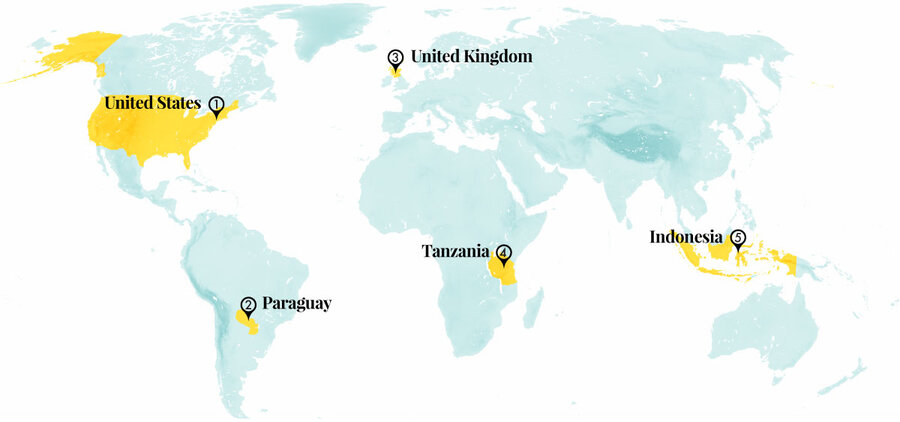

Environmental justice at work: From New Jersey water to Indonesian air

In our progress roundup, citizen activism carries risks, as some Indonesian villagers found when they were jailed for speaking up. But it also yields rewards, and just a few voices can make a big impact.

Environmental justice at work: From New Jersey water to Indonesian air

Collective action in three of our news briefs netted a city cleaner water, small-holder farmers more control, and citizens stronger legal rights to challenge corporate wrongdoing.

1. United States

Newark, New Jersey, has replaced nearly all city water pipes made of lead. Since 2019, utility workers have swapped out some 23,000 lead service lines. Congress banned the use of lead water pipes in 1986, but an estimated 6 million to 10 million lines remain active throughout the country. Lead exposure has been linked to serious health risks for adults and developmental issues in children, and disproportionately affects Black and low-income families. Newark leaders were initially reluctant to acknowledge the crisis, but community outcry and warnings from the Environmental Protection Agency pushed officials to act.

Armed with financial support from the state and county, a temporary workforce trained specifically for this project, and a new local ordinance that allowed the city to replace pipes without landowner consent, Newark has tackled what it planned as an eight-year project in less than half that time. At the project’s height, labor crews were replacing 125 lines a day, and are set to finish the project this fall. Water tests conducted in 2020 found the city was back under 15 micrograms of lead per liter, in compliance with EPA standards. (Read more about water and justice in the U.S. in this Monitor story.)

The New York Times, The Guardian, EPA

2. Paraguay

The resurgence of yerba maté herbal tea is helping to bring economic independence to small-scale farmers in Paraguay. For centuries, the tough green yerba maté leaves and herbal infusions brewed from them have been a major part of the country’s culture and economy. But when Europeans arrived in the 16th century, the industry became dominated by violent exploitation. Locals say the effects of that exploitation are still felt today in the government’s support for industrial agriculture, to the detriment of rural and Indigenous communities. The Oñoirũ Association of Agroecological Agriculture, a cohort of 134 small farming families, is working to change that dynamic. General Manager Pedro Vega says the democratically run group is “looking to create a fairer model of society using our natural resources, so that our young people can stay in their communities and have decent living and work conditions.”

Since launching in 2015 with NGO support, the group has been able to pay farming members more than the industrial buyers, create 20 jobs, and increase harvests by more than 250% as sales and membership grow. Its model prioritizes sustainable farming techniques and gender equality, with Oñoirũ bringing women into decision-making positions, educating communities on gender issues, and allowing women to develop and commercialize their own products.

The Guardian

3. United Kingdom

A new survey shows Scotland’s wild beaver population has more than doubled in the past three years. The Eurasian beaver has been extinct in the country since the 1500s, largely due to hunting for its meat, fur, and castoreum, a vanilla-scented secretion. Since 2009, formal and informal reintroduction initiatives – some controversial – have sought to restore the species. Environmental agency NatureScot found that beaver numbers in Scotland have surged to 1,000, up from an estimated 433 in 2017. The beavers also established 251 territories across the southern Highlands – a 120% increase since the last survey – colonizing rivers and lochs from Stirling to Glen Isla, just south of the Cairngorms National Park. The beavers play an important role in creating and maintaining wetlands, and are boosting nature tourism.

Beavers that destroy farmland or infrastructure can be removed under license either by trapping and relocating the beaver to a different nature site or, more commonly, through extermination. The NatureScot survey announced that 115 beavers were killed in 2020 under license, which some conservationists say is evidence that the group failed to prioritize humane forms of population control. NatureScot and the National Farmers Union say the policy allows for culling as a last resort.

BBC, The Guardian, The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

4. Tanzania

Women in Zanzibar are learning to farm natural sponges, a shift that safeguards their income and the environment. As climate change disrupts seaweed production and overfishing depletes fish populations, Tanzanian women who rely on the sea will need to diversify. Sea sponges – simple organisms that resemble porous rock – are more resilient to changing temperatures, require little maintenance, and can be sold to tourists and local hotels as a green alternative to synthetic sponges.

Nasir Hassan Haji, a single mother who, like many women on the island, was once a seaweed farmer, found out about marinecultures.org from a friend. The small Swiss charity is training women to swim and cultivate sea sponges, primarily in the fishing village of Jambiani. Ms. Haji is one of 13 women currently farming with the group, and more are trained each year. “I learned to swim and to farm sponges so I could be free and not depend on any man,” Ms. Haji said. “I am building my own house and educating my children. Women were left behind before, but now that is changing.”

Thomson Reuters Foundation, Marinecultures.org

5. Indonesia

The acquittal of six Bangka Island villagers is a precedent-setting first against frivolous litigation intended to silence environmental defenders, also known as SLAPP (strategic lawsuit against public participation). Residents have been fighting the PT Bangka Asindo Agri (BAA) tapioca company since 2017 over the factory’s pungent waste. In May 2020, a group of neighborhood unit heads began preparing a class-action lawsuit against the company. When the community planned a meeting to discuss the lawsuit, a neighbor reported the six organizers – who were no longer serving as neighborhood chiefs – to authorities for impersonating officials. The villagers believe BAA was behind the report, but the company denies involvement.

They spent more than three weeks in detention after a district court found the villagers guilty. But in August the province’s high court said the gathering was protected under an anti-SLAPP measure in the 2009 environmental protection law, affirming residents’ rights to campaign. Advocates celebrated the decision, but said a better backstop is needed in the form of a discrete anti-SLAPP law. “This is also an important moment for investigators to coordinate with ministers, the Attorney General’s Office and the police,” said Raynaldo Sembiring, executive director of the Indonesian Center for Environmental Law. “These institutions can build communication and stop [SLAPP] cases as early as possible.”

Mongabay

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A revival of public art as freedom from a pandemic

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For the German dramatist Bertolt Brecht, art was not a mirror of reality but a hammer with which to shape it. That idea may explain why so many cities are supporting artworks in public spaces during the pandemic. The art is safe to view and can lighten people’s spirits. It also helps restore a community’s social fabric.

The latest example comes from Italy. Over the weekend, residents along Venice’s Grand Canal were entertained by a wooden boat in the shape of a giant violin. On the deck was a string quartet playing the works of Vivaldi. Both the performance and the violin boat were a tribute to those lost to COVID-19 and a symbol of rebirth.

Then there is Paris. Although not originally designed during the pandemic, an ephemeral installation by the late artist Christo has drawn huge crowds since its opening Sept. 18. Before his death in May last year, Christo had arranged a wrapping of France’s most important monument, the 164-foot-high Arc de Triomphe.

As the pandemic recedes, many cities are again finding the liberating power of public culture.

A revival of public art as freedom from a pandemic

For the German dramatist Bertolt Brecht, art was not a mirror of reality but a hammer with which to shape it. That idea may explain why so many cities are supporting artworks in public spaces during the pandemic. The art is safe to view and can lighten people’s spirits. It also helps restore a community’s social fabric through a cultural vitality.

The latest example comes from Venice, the Italian city whose art and architecture are already pretty public. Over the weekend, residents along the Grand Canal were entertained by a 40-foot wooden boat in the shape of a giant violin. On the deck was a string quartet playing the works of Vivaldi, a famous musical son of Venice. Both the performance and the violin boat were a tribute to those lost to COVID-19 and a symbol of rebirth.

Also in September, Toronto launched the first of several temporary works designed to “rebuild our city post-pandemic and bring about a renewed sense of hope and vibrancy,” according to Mayor John Tory. The initial artwork is a sculpture of icebergs made almost entirely of plastic foam. It is described as a contrast to the impermanence of melting ice.

The city of Albuquerque has opened a temporary installation of more than 500 black and white paper flags designed by local artists. The flags represent different experiences of the pandemic. They reflect the “hardships and determination that defined our experiences through the pandemic,” says Mayor Tim Keller.

Then there is Paris. Although not originally designed during the pandemic, an ephemeral installation by the late artist Christo has drawn huge crowds since its opening Sept. 18. Before his death in May last year, Christo had arranged a wrapping of France’s most important monument, the 164-foot-high Arc de Triomphe on the Champs-Élysées. Wrapped in blue-gray fabric for just three weeks, the arch has been transformed from a tribute to Napoleon’s military conquests to one now seen as a liberation from a lockdown.

All of Christo’s works – most were wrappings – celebrated freedom, whether it is the free admission to see the works or the freedom to interpret them as one sees fit. The artist was known for not accepting limits, such as his bureaucratic battles to have his visions approved and installed.

As with most public art, everyone involved from officials to tourists is part of the work. They talk about the art and bring meaning to it, perhaps finding a common light in each other. In doing so, they weave new bonds of community. Or as Brecht might say, they are hammering a new reality. As the pandemic recedes, many cities are again finding the liberating power of public culture.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Embrace the wilderness

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Karyn Mandan

Sometimes life’s challenges may make us feel alone and adrift. But we can let God’s love bring healing, joy, and light to our path – as a woman experienced after the loss of her mom and stepdad.

Embrace the wilderness

Desolation Wilderness.

This region at the crest of the Sierra Nevada mountains is a barren expanse of granite peaks near the edge of the tree line. It is a rugged and unyielding terrain, but also magnificent in its vast, endless beauty. It’s one of my favorite places to hike, with my persistence frequently rewarded by breathtaking vistas and the discovery of hidden lakes.

A few summers ago, this hike gave me a vivid insight into the unlimited good that comes from God, our divine Father-Mother, infinite Love.

Some months before the hike, I was deep in grief over the passing of my stepdad and mom, followed by our family dog. It was a dark period of loss and loneliness. When I was a teenager, my father died, and my stepdad’s kindness and steadiness became a ballast in my life. Deprived of him and my mom now, I felt weak and vulnerable.

In tears, I reached out in prayer for comfort. Through my study of Christian Science and the light it throws on the Scriptures, I was learning that God, divine Love, is our creator, maintainer, and sustainer. We naturally reflect all the qualities of our divine Parent. I reasoned spiritually, “Would God give gifts to one person and not to another? Would God give spiritual qualities to my family and withhold them from me?” No! Although we each express divine qualities in unique ways, we all possess the fullness of God’s goodness and ability to express it in our lives.

This gentle reminder – that the source and substance of good isn’t a human, but divine Love – fortified me.

In a flash of insight one day I realized, “This is the wilderness!” It immediately brought to mind the biblical account of the ancient Israelites’ 40-year journey from captivity in Egypt to the Promised Land. They traveled through the wilderness, a disorienting and difficult period.

But they weren’t left to navigate it alone. God led them “by day in a pillar of a cloud ... and by night in a pillar of fire” (Exodus 13:21). At times they struggled mightily, complaining that their leader, Moses, had surely brought them to this inhospitable place to die. Yet the account illustrates that they were never separated from God’s care. God provided fresh food and water to sustain them, and eventually they did reach the Promised Land.

The lesson they needed to learn was that God preserves all His children. Their purpose, then, was not to merely survive, it was to trust and love God supremely! The New King James Version puts it this way: “Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one! You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your strength” (Deuteronomy 6:4, 5).

In “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, a glossary of biblical terms includes this twofold metaphysical definition of “wilderness”: “Loneliness; doubt; darkness. Spontaneity of thought and idea; the vestibule in which a material sense of things disappears, and spiritual sense unfolds the great facts of existence” (p. 597).

I applied this to the “wilderness experience” I was going through: Rather than fearing the unknown, I could trust the infinite to lead me. Whenever grief threatened to overwhelm me, these ideas roused me to embrace the wilderness in which “spiritual sense unfolds the great facts of existence.”

Those spiritual facts include God’s ever-present, constant love, which is expressed in each of us without measure. No matter the human circumstance, we are never separated from God’s sustaining, practical care. We can trust divine help and inspiration to meet the challenges of daily life.

As I glimpsed these truths, the grief and darkness lifted. I let go of a limiting reliance on human help alone.

And this is when I embarked on a day’s hike in Desolation Wilderness. Seeing the sign, I suddenly realized in awe how far God had brought me through this trying time, sustaining and guiding me. Even when I thought what was dearest to me had been lost, I found that trust and love of God deeply blessed my life, which continued to expand and blossom in new and unexpected ways.

On that granite crest, I felt free – free to love my stepdad, my mom, and our dog with gratitude instead of grief, and to let this love flow outward to others. I embraced the lesson of the wilderness!

A message of love

River crossing

A look ahead

Thanks for starting your week with us! Tomorrow, Noah Robertson will report from Racine, Wisconsin, where, in a bid to build trust between police and community, the city bought homes in at-risk neighborhoods and asked officers to live in them. It’s the next installment in our Policing in America series.